Pharaonic Egypt and the Ara Pacis in Augustan Rome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Domitian's Arae Incendii Neroniani in New Flavian Rome

Rising from the Ashes: Domitian’s Arae Incendii Neroniani in New Flavian Rome Lea K. Cline In the August 1888 edition of the Notizie degli Scavi, profes- on a base of two steps; it is a long, solid rectangle, 6.25 m sors Guliermo Gatti and Rodolfo Lanciani announced the deep, 3.25 m wide, and 1.26 m high (lacking its crown). rediscovery of a Domitianic altar on the Quirinal hill during These dimensions make it the second largest public altar to the construction of the Casa Reale (Figures 1 and 2).1 This survive in the ancient capital. Built of travertine and revet- altar, found in situ on the southeast side of the Alta Semita ted in marble, this altar lacks sculptural decoration. Only its (an important northern thoroughfare) adjacent to the church inscription identifies it as an Ara Incendii Neroniani, an altar of San Andrea al Quirinale, was not unknown to scholars.2 erected in fulfillment of a vow made after the great fire of The site was discovered, but not excavated, in 1644 when Nero (A.D. 64).7 Pope Urban VIII (Maffeo Barberini) and Gianlorenzo Bernini Archaeological evidence attests to two other altars, laid the foundations of San Andrea al Quirinale; at that time, bearing identical inscriptions, excavated in the sixteenth the inscription was removed to the Vatican, and then the and seventeenth centuries; the Ara Incendii Neroniani found altar was essentially forgotten.3 Lanciani’s notes from May on the Quirinal was the last of the three to be discovered.8 22, 1889, describe a fairly intact structure—a travertine block Little is known of the two other altars; one, presumably altar with remnants of a marble base molding on two sides.4 found on the Vatican plain, was reportedly used as building Although the altar’s inscription was not in situ, Lanciani refers material for the basilica of St. -

The Mythology of the Ara Pacis Augustae: Iconography and Symbolism of the Western Side

Acta Ant. Hung. 55, 2015, 17–43 DOI: 10.1556/068.2015.55.1–4.2 DAN-TUDOR IONESCU THE MYTHOLOGY OF THE ARA PACIS AUGUSTAE: ICONOGRAPHY AND SYMBOLISM OF THE WESTERN SIDE Summary: The guiding idea of my article is to see the mythical and political ideology conveyed by the western side of the Ara Pacis Augustae in a (hopefully) new light. The Augustan ideology of power is in the modest opinion of the author intimately intertwined with the myths and legends concerning the Pri- mordia Romae. Augustus strove very hard to be seen by his contemporaries as the Novus Romulus and as the providential leader (fatalis dux, an expression loved by Augustan poetry) under the protection of the traditional Roman gods and especially of Apollo, the Greek god who has been early on adopted (and adapted) by Roman mythology and religion. Key words: Apollo, Ara, Augustus, Pax Augusta, Roma Aeterna, Saeculum Augustum, Victoria The aim of my communication is to describe and interpret the human figures that ap- pear on the external western upper frieze (e.g., on the two sides of the staircase) of the Ara Pacis Augustae, especially from a mythological and ideological (i.e., defined in the terms of Augustan political ideology) point of view. I have deliberately chosen to omit from my presentation the procession or gathering of human figures on both the Northern and on the Southern upper frieze of the outer wall of the Ara Pacis, since their relationship with the iconography of the Western and of the Eastern outer-upper friezes of this famous monument is indirect, although essential, at least in my humble opinion. -

ROME : ART and HISTORY OPENAIR 2020-2021, 2Nd Semester Meeting 1 – 13.03.2021 the Eternal City

University of Rome Tor Vergata School of Global Governance Prof. Anna Vyazemtseva ROME : ART AND HISTORY OPENAIR 2020-2021, 2nd semester Meeting 1 – 13.03.2021 The Eternal City 10 am – 5 pm :, The Palatine (Domus Augustana, Horti Farnesiani), Roman and Imperial Forums, The Colosseum, Vittoriano Complex, Musei Capitolini. 1 - 2pm:Lunch Meeting 2 – 20.03.2021 Introduction to the Renaissance 10 am – 5 pm: St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican Museums (Sistine Chapel by Michelangelo, Stanze by Raphael). 1 - 2pm: Lunch Meeting 3 – 27.03.2021 Architecture and Power: Palaces of Rome 10 am – 5 pm: Villa Farnesina, Via Giulia, Palazzo Farnese, Palazzo Spada-Capodiferro, Palazzo della Cancelleria, Palazzo Mattei, Palazzo Venezia 1 - 2pm: Lunch Meeting 4 – 10.04.2021 Society, Politics and Art in Rome in XV-XVIII cc. 10 am – 5 pm: Santa Maria del Popolo, Piazza di Spagna, Barberini Palace and Gallery, Fon tana di Trevi, San Carlino alle Quattro Fontane, Sant’Andrea al Quirinale, Palazzo del Quirinale 1 - 2pm:Lunch Meeting 5 – 14.04.2021 The Re-use of the Past 10 am – 5 pm: Pantheon, Piazza di Pietra, Piazza Navona, Baths of Diocletian, National Archeological Museum Palazzo Massimo alle Terme. 1 - 2pm: Lunch Meeting 6 – 08.03.2021 Contemporary Architecture in Rome 10 am – 5pm: EUR district, MAXXI – Museum of Arts of XXI c. (Zaha Hadid Architects), Ara Pacis Museum. 1 – 2 pm: Lunch Proposals and Requirements The course consists of 6 open air lectures on artistic heritage of Rome. The direct contact with sites, buildings and works of art provides not only a better comprehension of their historical and artistic importance but also helps to understand the role of heritage in contemporary society. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

The Karnak Project Sébastien Biston-Moulin, Christophe Thiers

The Karnak Project Sébastien Biston-Moulin, Christophe Thiers To cite this version: Sébastien Biston-Moulin, Christophe Thiers. The Karnak Project: A Comprehensive Edition of the Largest Ancient Egyptian Temple. Annamaria De Santis (Université de Pise); Irene Rossi (CNR - ISMA). Crossing Experiences in Digital Epigraphy. From Practice to Discipline, De Gruyter Open, pp.155-164, 2018, 9783110607208. 10.1515/9783110607208-013. halshs-02056329 HAL Id: halshs-02056329 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02056329 Submitted on 4 Mar 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License Annamaria De Santis and Irene Rossi (Eds.) Crossing Experiences in Digital Epigraphy From Practice to Discipline Managing Editor: Katarzyna Michalak Associate Editors: Francesca Corazza and Łukasz Połczyński Language Editor: Rebecca Crozier ISBN 978-3-11-060719-2 e-ISBN 978-3-11-060720-8 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0) For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 © 2018 Annamaria De Santis, Irene Rossi and chapters’ contributors Published by De Gruyter Poland Ltd, Warsaw/Berlin Part of Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com. -

Ara Pacis (13-9 BCE) Architecture Published on Judaism and Rome (

Ara Pacis (13-9 BCE)_Architecture Published on Judaism and Rome (https://www.judaism-and-rome.org) Ara Pacis (13-9 BCE)_Architecture Reconstruction of the Ara Pacis [1] Ara Pacis: frontal view [2] [3] Ara Pacis: side view [4] [5] Ara Pacis: side view [6] [7] Patron/Sponsor: Senate Original Location/Place: Rome: Campus Martius Actual Location (Collection/Museum): In loco Date: 9 BCE Material: Marble Page 1 of 4 Ara Pacis (13-9 BCE)_Architecture Published on Judaism and Rome (https://www.judaism-and-rome.org) Measurements: 11.6 m by 10.6 m by 3.6 m Building Typology: Altar Description: The Ara Pacis Augustae is a monumental altar. The altar, which is set on a four steps base, was sculpted in marble from Luna. The altar is surrounded by walls. There are two gates, the first located on the eastern wall and the other on the western one. Four Corinthian pilasters are set at the corners and at the doorways. The decoration on the exterior of the precinct walls is characterized by reliefs set on two registers. The lower register of the frieze consists in acanthus scrolls filled by small animals and birds. The upper part of the altar is decorated with garlands of fruits and leaves suspended between bucrania, or decorations shaped as oxen’s skulls, from fluttering ribbons. The loops made by the garlands are filled with free-floating paterae, or metal libation bowls. On the northern and southern walls, the upper register depicts the sacrfical procession of members of the imperial household, together with priests and lictors. -

The Power of Images in the Age of Mussolini

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 The Power of Images in the Age of Mussolini Valentina Follo University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Follo, Valentina, "The Power of Images in the Age of Mussolini" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 858. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/858 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/858 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Power of Images in the Age of Mussolini Abstract The year 1937 marked the bimillenary of the birth of Augustus. With characteristic pomp and vigor, Benito Mussolini undertook numerous initiatives keyed to the occasion, including the opening of the Mostra Augustea della Romanità , the restoration of the Ara Pacis , and the reconstruction of Piazza Augusto Imperatore. New excavation campaigns were inaugurated at Augustan sites throughout the peninsula, while the state issued a series of commemorative stamps and medallions focused on ancient Rome. In the same year, Mussolini inaugurated an impressive square named Forum Imperii, situated within the Foro Mussolini - known today as the Foro Italico, in celebration of the first anniversary of his Ethiopian conquest. The Forum Imperii's decorative program included large-scale black and white figural mosaics flanked by rows of marble blocks; each of these featured inscriptions boasting about key events in the regime's history. This work examines the iconography of the Forum Imperii's mosaic decorative program and situates these visual statements into a broader discourse that encompasses the panorama of images that circulated in abundance throughout Italy and its colonies. -

A Nome Procession from the Royal Cult Complex in the Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir El-Bahari 20 O��� B��������

INSTITUT DES CULTURES MÉDITERRANÉENNES ET ORIENTALES DE L’ACADÉMIE POLONAISE DES SCIENCES ÉTUDES et TRAVAUX XXVII 2014 O B A Nome Procession from the Royal Cult Complex in the Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari 20 O B The term ‘nome procession’ refers to an iconographic sequence of nome personifi cations depicted mostly on the lowest level of temples or shrines. The fi gures are usually represented in a procession around the edifi ce, bringing offerings for the cult of the deity or the king worshiped inside. They follow the geographic order from south to north, in line with the traditional Egyptian system of orientation which gives precedence to the southern direction.1 The present study deals with one such procession of nome personifi cations represented in the Temple of Queen Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari. The scene in question covers the eastern wall of a small, open courtyard in the Complex of the Royal Cult situated south of the main Upper Courtyard of the Temple. The small court precedes two vestibules which further lead to adjacent two cult chapels. The bigger vestibule, belonging to the Chapel of Hatshepsut, is attached to the southern side of the courtyard, whereas on the western side of the latter lie the second, much smaller vestibule and a cult chapel dedicated to the Queen’s father, Tuthmosis I. From the architectural point of view, the eastern wall of the small courtyard partly delimits the Royal Cult Complex from the east. Iconographically, the whole eastern wall of the Complex is divided into two sections, each one belonging to a different piece of this cultic compound: the northern part, decorated in sunken relief, stretches for 3.71m (which equals 7 cubits) and belongs to the said small courtyard; the southern section – 5.81m long (approx. -

Best Architecture & Design in Rome

"Best Architecture & Design in Rome" Erstellt von : Cityseeker 4 Vorgemerkte Orte Museo d'Arte Ebraica "Ein Volk, das kämpft" Bei Besichtigung des Museums erhalten Sie auch Zutritt zur Synagoge. Zu den glanzvollen Exponaten gehören prunkvolle Kronen, Silbergegenstände und Thoras, Umhänge, die die Juden zum Gebet überziehen. In einer Abteilung ist eine Ausstellung über die Verfolgungen, die das jüdische Volk im Laufe von zwei Jahrtausenden erlitt. Zum by Public Domain Beispiel eine Kopie des päpstlichen Edikts aus dem 16. Jahrhundert, das den Juden die Ausübung verschiedener Tätigkeiten untersagte, und Zeugnisse aus den Konzentrationslagern der Nazi-Zeit. Die mächtige Synagoge neben dem Museum, die auf den Tiber blickt, wurde 1870 errichtet. Eintritt EUR4; Schulklassen EUR3 +39 06 684 0061 www.museoebraico.roma.i [email protected] Lungotevere Cenci, Tempio t/ Maggiore di Roma, Rom Museo dell'Ara Pacis "Museum for Peace Altar" The Ara Pacis Museum is one of the most beautiful museums in Rome, dedicated to the ancient Ara Pacis (Altar of Peace). The altar itself is from the year 9 B.C. The museum was designed by American architect Richard Meier, who created a wonderful space of light and shadow. The central pavilion holds the Ara Pacis, which is illuminated by natural light filtered by Public Domain through 500 square meters of glass. +39 06 0608 www.arapacis.it/ [email protected] Lungotevere in Augusta, a.it Rom Casa dell'Architettura "Art & Architecture" The Casa dell'Architettura came into being due to the efforts of the Municipality of Rome and the Association of Architects of Rome who recognized the need for an exclusive cultural space. -

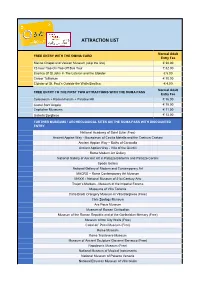

Attraction List

ATTRACTION LIST Normal Adult FREE ENTRY WITH THE OMNIA CARD Entry Fee Sistine Chapel and Vatican Museum (skip the line) € 30.00 72-hour Hop-On Hop-Off Bus Tour € 32.00 Basilica Of St.John In The Lateran and the Cloister € 5.00 Carcer Tullianum € 10.00 Cloister of St. Paul’s Outside the Walls Basilica € 4.00 Normal Adult FREE ENTRY TO THE FIRST TWO ATTRACTIONS WITH THE ROMA PASS Entry Fee Colosseum + Roman Forum + Palatine Hill € 16.00 Castel Sant’Angelo € 15.00 Capitoline Museums € 11.50 Galleria Borghese € 13.00 FURTHER MUSEUMS / ARCHEOLOGICAL SITES ON THE ROMA PASS WITH DISCOUNTED ENTRY National Academy of Saint Luke (Free) Ancient Appian Way - Mausoleum of Cecilia Metella and the Castrum Caetani Ancient Appian Way – Baths of Caracalla Ancient Appian Way - Villa of the Quintili Rome Modern Art Gallery National Gallery of Ancient Art in Palazzo Barberini and Palazzo Corsini Spada Gallery National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art MACRO – Rome Contemporary Art Museum MAXXI - National Museum of 21st Century Arts Trajan’s Markets - Museum of the Imperial Forums Museums of Villa Torlonia Carlo Bilotti Orangery Museum in Villa Borghese (Free) Civic Zoology Museum Ara Pacis Museum Museum of Roman Civilization Museum of the Roman Republic and of the Garibaldian Memory (Free) Museum of the City Walls (Free) Casal de’ Pazzi Museum (Free) Rome Museum Rome Trastevere Museum Museum of Ancient Sculpture Giovanni Barracco (Free) Napoleonic Museum (Free) National Museum of Musical Instruments National Museum of Palazzo Venezia National Etruscan -

Amenhotep I Limestone Chapel

Amenhotep I Limestone Chapel Originally built by Amenhotep I - 1525 BCE to 1504 BCE (Show in timemap) Destroyed by: Amenhotep III - 1390 BCE to 1352 BCE ( (Show in timemap)) Other works initiated by Amenhotep I: Middle Kingdom Court, Amenhotep I Calcite Chapel Other works destroyed by Amenhotep III: Thutmose IV Peristyle Hall, Obelisks of Festival Hall West Pair, White Chapel, Amenhotep II Shrine, Pylon and Fes- tival Court of Thutmose II Other shrines: Amenhotep I Calcite Chapel, Amenhotep II Shrine, Contra Tem- ple, Osiris Catacombs, Osiris Coptite, Osiris Heqa-Djet, Palace of Ma’at, Central Bark Shrine, Ramesses II Eastern Temple, Ramesses III Temple, Red Chapel, Sety II Shrine, Taharqo Kiosk, Thutmose III Shrine, White Chapel, Edifice of Amenhotep II, Chapel of Hakoris, Station of the King and Corridor Introduction The limestone chapel of Amenhotep I was a replica of the “white chapel” of Middle Kingdom king Senusret I. The chapel was almost identical in size and design to the earlier “white chapel.” Both may originally have stood to the west of the temple precinct. Measurements: Each of the columns measure 2.56m in height and are approxi- mately 0.6m across and 0.6m deep. The platform on which the columns rest is 1.18m high and 6.80m by 6.45m. Phase: Amenhotep I The chapel may have served as a statue shrine or portable bark shrine for the image of Amun-Ra or the king. The chapel seems to have remained standing long enough to be incorporated into the “festival hall” of king Thutmose II. Construction materials: limestone Renderings of the Limestone Chapel as completed during the reign of Amenhotep I. -

ANTHRO 138TS: ARCHAEOLOGY of EGYPT FINAL STUDY GUIDE Œ Ñ Ú, Etc

ANTHRO 138TS: ARCHAEOLOGY OF EGYPT F I N A L S T U D Y G U I D E Short Answer Identifications: Some of these ID’s overlap with the mid- term – emphasize the 2nd half of class. 4 bulleted points for each. Anubis Edfu Sympathetic Magic Ba-Ka-Akh Elephantine Deben Merwer John Wilson Canopic Jars “White Chapel” Bes Wilbour Papyrus (peripteral shrine) Defuffa Sed Festival Ennead Napata Mummification Odgoad Medamud Hellenism/Hellenistic Syncretism Kahun Hor-Apollo Ushabti Mastaba Karl Polanyi Elephantine Serdab Ostraca Harim Conspiracy T-Shaped Tomb Paneb Min/Min-Amun/Min- Letter to the Dead George Reisner Horus Book of the Dead Neo-Platonic Philosophy Sympathetic Magic Am Duat Per-aa Formalist-Substantivist Meketre Palermo Stone Shuty Apademak Semna Despatches Deir el-Medina Amanatore Ramesseum Temple of Satet Hekanakht Taweret Picture Identifications: The following list refers to images from the Silverman text. One bulleted point for each. Rahotep & Nofret Taharqa Opening of Mouth Sennedjem Bastet Ba Ka-aper Antinous Execration Figure Khamuas Sat-Hathor-Iunet Mutemonet Canon of Proportion Selqet Sobek Bes Hathor Scarab Taweret Thoth Horus Buhen Ramose Rameses II – Ra-mes-su Mastaba Meresankh Wedjat (Eye of Horus) Thuya Hunefer Œ Ñ ú, etc. ANTHRO 138TS: ARCHAEOLOGY OF EGYPT Essays: There will be two essays, one from the Final Study Guide and a comprehensive essay question on a large theme from both halves of class. For all of the essays you will have a choice between two questions to answer. S T U D Y Q U E S T I O N S 1.