Reclaiming Liberalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COSMOS + TAXIS | Volume 9 Issue 3+4 2021

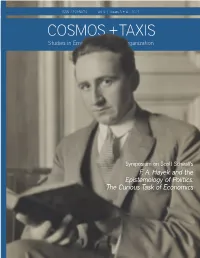

ISSN 2291-5079 Vol 9 | Issues 3 + 4 2021 COSMOS + TAXIS Studies in Emergent Order and Organization Symposium on Scott Scheall's F. A. Hayek and the Epistemology of Politics: The Curious Task of Economics COVER IMAGE F. A. Hayek COSMOS + TAXIS Friedrich von Hayek: His Nobel Prize and Family Studies in Emergent Order and Organization Collection VOLUME 9 | ISSUES 3 + 4 2021 Sotheby's online auction, March 2019. EDITORIAL BOARDS HONORARY FOUNDING EDITORS EDITORS SYMPOSIUM ON SCOTT SCHEALL'S Joaquin Fuster Leslie Marsh* F. A. HAYEK AND THE EPISTEMOLOGY University of California, Los Angeles (editor-in-chief) David F. Hardwick* The University of British Columbia OF POLITICS: THE CURIOUS TASK OF The University of British Columbia William N. Butos Lawrence Wai-Chung Lai (deputy editor) ECONOMICS University of Hong Kong Trinity College Frederick Turner Laurent Dobuzinskis* University of Texas at Dallas (deputy editor) Simon Fraser University Editorial Introduction ....................................1 Giovanni B. Grandi William N. Butos (deputy editor) The University of British Columbia Symposium Prologue ................................... 2 Nathan Robert Cockeram (assistant editor) Scott Scheall The University of British Columbia Epistemics and Economics, Political Economy CONSULTING EDITORS and Social Philosophy ..................................9 Thierry Aimar Ted G. Lewis Peter Boettke Sciences Po Paris Technology Assessment Group, Nurit Alfasi Salinas Ben Gurion University of the Negev Joseph Isaac Lifshitz The Political Process: Experimentation -

After Revolution : Reading Rousseau in 1990S China

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. After revolution : reading Rousseau in 1990s China van Dongen, Els; Chang, Yuan 2017 van Dongen, E., & Chang, Y. (2017). After revolution : reading Rousseau in 1990s China. Contemporary Chinese Thought, 48(1), 1‑13. doi:10.1080/10971467.2017.1383805 https://hdl.handle.net/10356/143782 https://doi.org/10.1080/10971467.2017.1383805 This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Contemporary Chinese Thought on 14 Dec 2017, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/10971467.2017.1383805. Downloaded on 29 Sep 2021 15:15:43 SGT The final version of this article was published in Contemporary Chinese Thought 48.1 (2017): 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10971467.2017.1383805 Introduction After Revolution: Reading Rousseau in 1990s China Els van Dongen and Yuan Chang Abstract This article reviews Zhu Xueqin’s (b. 1952) writings on Jean-Jacques Rousseau against the background of the reception of Rousseau in China since the late nineteenth century. Rousseau was both an advocate and critic of the Enlightenment, and his work hence appealed to many Chinese intellectuals who struggled with the conundrum of how to modernize. During the late nineteenth century, Chinese supporters of Rousseau drew on his work to defend the viability of revolution. During the 1990s, following the tragedy of Tiananmen and the decline of socialism, Rousseau served to reflect on China’s twentieth-century trajectory and the disastrous political consequences of collective moral idealism. For Zhu Xueqin, a key question was: Why were the French Revolution and the Cultural Revolution so similar? Rousseau and the Double-Edged Sword of Modernity In the history of modern Western political thought, few have managed to achieve the fame and influence of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778). -

ANDREW DAVID IRVINE, Phd University of British Columbia Okanagan

Curriculum Vitae ANDREW DAVID IRVINE, PhD University of British Columbia Okanagan Professor Department of Economics, Philosophy & Political Science Department of Computer Science, Mathematics, Physics & Statistics University of British Columbia Okanagan Kelowna, BC Canada V1V 1V7 Tel. 250-807-9704 Email. [email protected] 30 June 2020 Often cited for his work on the twentieth-century Nobel laureate Bertrand Russell, Andrew Irvine is a past head of the Department of Economics, Philosophy and Political Science at UBC Okanagan, a past senior advisor to the UBC president and a past vice- chair of the UBC Board of Governors. In his academic work, he has argued in favour of a physicalist world view and against several commonly held positions in contemporary philosophy, including the view that Gottlob Frege succeeded in developing a workable theory of mathematical Platonism and the view that Bertrand Russell was an advocate of epistemic logicism, a claim one commentator has concluded is now “thoroughly debunked.” He has defended a two-box solution to Newcomb’s problem, in which he abandons “the (false) assumption that past observed frequency is an infallible guide to probability.” He has also defended a non-cognitivist solution to the liar paradox, noting that “formal criteria alone will inevitably prove insufficient” for determining whether individual sentence tokens have meaning. In modal logic, he has argued in favour of the non-normal system S7, rather than more traditional systems such as S4 or S5, holding that unlike other systems, S7 allows logicians to choose between competing logics, each of whose theorems, if true, would be necessarily true, but none of which are necessarily the correct system of necessary truths. -

Irvine ORIGINS 2019.Pdf

Forthcoming in David Hardwick and Leslie Marsh (eds), Reclaiming Liberalism, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019 ORIGINS OF THE RULE OF LAW Andrew David Irvine University of British Columbia, Okanagan Introduction Central to the idea of the rule of law is the requirement that even governments must be bound by law.1 Under the rule of law, even those who have the ability to make and change the law remain subject to it. Even those who have the power to interpret and enforce the law remain governed by it. It is this feature of law, as much as the ballot box or the free press, that protects the ordinary citizen from arbitrary state power.2 Understood in this way, the rule of law is more than just the requirement that governments must act according to the law. Should a law be passed that gave a government the power to act whenever and however it wanted, such a government would not be bound by law. To be genuine, rule of law must place substantial, non-trivial constraints on the use of state power, just as it does with ordinary citizens. It requires not only that government authority be exercised in accordance with publicly disclosed and appropriately adopted procedures.3 It also requires that genuine prohibitions exist against 2 at least some types of state action. It is in this sense that rule of law differs from rule by law or rule through law. Simply put, rule of law requires not just that all government actions find their source in law. It also requires governments to acknowledge the difference between powers granted to them in law and powers they do not have. -

Volume 9 Issue 7+8 2021

ISSN 2291-5079 Vol 9 | Issue 7 + 8 2021 COSMOS + TAXIS Studies in Emergent Order and Organization COVER IMAGE George Gilbert Scott´s Grand Staircase at COSMOS + TAXIS St. Pancras, London. Studies in Emergent Order and Organization Courtesy of Josephine R. Unglaub VOLUME 9 | ISSUE 7 + 8 2021 https://lemanshots.wordpress.com IN THIS ISSUE EDITORIAL BOARDS HONORARY FOUNDING EDITORS EDITORS Outgrowing Methodological Individualism: Joaquin Fuster Leslie Marsh* Emergence, spontaneous orders, and civil society ..........1 University of California, Los Angeles (editor-in-chief) David F. Hardwick*† The University of British Columbia Gus diZerega The University of British Columbia William N. Butos Lawrence Wai-Chung Lai (deputy editor) What is a Legislature’s Purpose? .......................26 University of Hong Kong Trinity College Thomas J. McQuade Frederick Turner Laurent Dobuzinskis* University of Texas at Dallas (deputy editor) Simon Fraser University Modeling the Spread of COVID-19 Using a Novel Threat Giovanni B. Grandi Surface ...............................................41 (deputy editor) Ted G. Lewis and Waleed I. Al Mannai The University of British Columbia Nathan Robert Cockeram (assistant editor) An informal introduction to Michael Oakeshott’s The University of British Columbia vision of a free, civilized and affirmative life. ..............51 Noël O’Sullivan CONSULTING EDITORS Thierry Aimar Ted G. Lewis Sciences Po Paris Technology Assessment Group, Nurit Alfasi Salinas REVIEWS Ben Gurion University of the Negev Joseph Isaac Lifshitz -

Prelim Test 2

47th Annual ISA Convention San Diego, CA March 22-25, 2006 “The North-South Divide and International Studies” William Thompson, 2006 ISA President Rafael Reuveny, 2006 ISA Program Chair ___________________________________________________________________________ Final Program Updated on 3/29/2006 at 2:28:20 PM ___________________________________________________________________________ WA01 Wednesday 8:30 - 10:15 AM Theory and Practice of Foreign Policy: Roundtable in Honor of Davis B. Bobrow Sponsors Foreign Policy Analysis Chair(s) Steve S. Chan University of Colorado Roundtable Discussants Mark A. Boyer University of Connecticut Terrence P. Hopmann Brown University Robert T. Kudrle University of Minnesota Chung-in Moon Yonsei Univerisity, Korea Donald A. Sylvan Ohio State University ___________________________________________________________________________ WA02 Wednesday 8:30 - 10:15 AM Europe and Latin America (I): Conflicting Priorities Sponsors Mexican International Studies Association (AMEI) Chair(s) Joaquín Roy University of Miami An Assessment of the EU-Latin American and Caribbean Summits Alejandro Chanona Center for European Studies, UNAM The Enhancement of Regional Latin American Integration in the Frame of the Strategic Association Between the European Union and Latin America and the Caribbean Thomas Cieslik Tecnológico de Monterrey The Influence of Transnational Non-Governmental Networks on the Application of EU-Latin America Cooperation Agreements Marcela Szymanski Katholieke Universiteit Leuven Discussant(s) Joaquín Roy -

9783030287597.Pdf

PALGRAVE STUDIES IN CLASSICAL LIBERALISM SERIES EDITORS: DAVID F. HARDWICK · LESLIE MARSH Reclaiming Liberalism Edited by David F. Hardwick · Leslie Marsh Palgrave Studies in Classical Liberalism Series Editors David F. Hardwick Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine The University of British Columbia Vancouver, BC, Canada Leslie Marsh Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine The University of British Columbia Vancouver, BC, Canada This series offers a forum to writers concerned that the central presup- positions of the liberal tradition have been severely corroded, neglected, or misappropriated by overly rationalistic and constructivist approaches. The hardest-won achievement of the liberal tradition has been the wrestling of epistemic independence from overwhelming concentrations of power, monopolies and capricious zealotries. The very precondition of knowledge is the exploitation of the epistemic virtues accorded by soci- ety’s situated and distributed manifold of spontaneous orders, the DNA of the modern civil condition. With the confluence of interest in situated and distributed liberalism emanating from the Scottish tradition, Austrian and behavioral econom- ics, non-Cartesian philosophy and moral psychology, the editors are soliciting proposals that speak to this multidisciplinary constituency. Sole or joint authorship submissions are welcome as are edited collections, broadly theoretical or topical in nature. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/15722 David F. Hardwick • Leslie -

Download File

The Making of Liberal Intellectuals in Post-Tiananmen China Junpeng Li Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2017 © 2017 Junpeng Li All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Making of Liberal Intellectuals in Post-Tiananmen China Junpeng Li Intellectual elites have been the collective agents responsible for many democratic transitions worldwide since the early twentieth century. Intellectuals, however, have also been blamed for the evils in modern times. Instead of engaging in abstract debates about who the intellectuals are and what they do, this project studies intellectuals and their ideas within historical contexts. More specifically, it examines the social forces behind the evolving political attitudes of Chinese intellectuals from the late 1970s to the present. Chinese politics has received an enormous amount of attention from social scientists, but intellectuals have been much less explored systematically in social sciences, despite their significant role in China’s political life. Chinese intellectuals have been more fully investigated in the humanities, but existing research either treats different “school of thought” as given, or gives insufficient attention to the division among the intellectuals. It should also be noted that many studies explicitly take sides by engaging in polemics. To date, little work has thoroughly addressed the diversity and evolution, let alone origins, of political ideas in post-Mao China. As a result, scholars unfamiliar with Chinese politics are often confused about the labels in the Chinese intelligentsia, such as the association of nationalism with the Left and human rights with the Right. -

Downloaded From

Goodbye Radicalism! Conceptions of conservatism among Chinese intellectuals during the early 1990s Dongen, E. van Citation Dongen, E. van. (2009, September 2). Goodbye Radicalism! Conceptions of conservatism among Chinese intellectuals during the early 1990s. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/13949 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/13949 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). “GOODBYE RADICALISM!” CONCEPTIONS OF CONSERVATISM AMONG CHINESE INTELLECTUALS DURING THE EARLY 1990S ELS VAN DONGEN Printed by Wöhrmann Print Service © 2009, E. van Dongen, Leiden, The Netherlands “GOODBYE RADICALISM!” CONCEPTIONS OF CONSERVATISM AMONG CHINESE INTELLECTUALS DURING THE EARLY 1990S PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van Rector Magnificus Prof. mr. P.F. van der Heijden, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op dinsdag 2 september 2009 klokke 11.15 uur door Els van Dongen geboren te Antwerpen, België in 1979 PROMOTIECOMMISSIE Promotor: Prof. dr. A. Schneider Mede-promotor: Prof. dr. R. Kersten (ANU) Overige leden: Prof. dr. C. Defoort (KUL) Prof. dr. J. Fewsmith (Boston University) Prof. dr. C. Goto-Jones This research was financially supported by a VICI Grant from the Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (NWO) and by a Fulbright Grant from the Fulbright Center in Amsterdam (formerly NACEE). Are we to paint what’s on the face, what’s inside the face, or what’s behind it? PABLO PICASSO ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would have never embarked on this journey of a thousand li without those who taught me to walk—my Professors at the Catholic University of Leuven. -

JULY 2020 Page 12 CONTENTS

C2CC2CJOURNAL JOURNAL | JULY 2020 page 12 CONTENTS Thirteen Things That Can’t Be Said About Aboriginal Law And Policy In Canada PAGE 1 Bruce Pardy How do you make new laws and policies or reform old ones in a democracy? You talk openly about every aspect, carefully consider the pros and cons and the long-term implications, and strive to come up with solutions that are fair to everyone. That has been the ideal, anyway, in Canada since Confederation. So what happens when vast areas of law and policy cannot even be discussed any longer? Bruce Pardy lists the things that have become perilous to say regarding Indigenous issues – but that need to be said if Canada is to maintain a legal system that is fair to all Canadians. The WE Charity Scandal: One Of Many PAGE 7 Grant A. Brown While it remains too soon to tell whether the WE Charity scandal will finally be the one that truly sticks to the Liberals and their leader, it has entirely consumed Justin Trudeau’s Covid-crisis bounce. Opposition parties are attempting to delve deeper, and even the mainstream media have shown more than a passing interest. It could get nasty indeed for the Liberals. Yet as Grant A. Brown points out, there’s so much more! As bad as WE may be, Brown urges us hold on a second and keep most of our outrage in reserve, for there’s a lot more Liberal wrongdoing where that came from. Escaping The Echo Chamber PAGE 14 Andrew David Irvine Copernicus disproved Ptolemy. -

China's Ideological Spectrum

China’s Ideological Spectrum A Two-dimensional Model of Elite Intellectuals’ Visions Mulvad, Andreas Møller Document Version Accepted author manuscript Published in: Theory and Society DOI: 10.1007/s11186-018-9326-6 Publication date: 2018 License Unspecified Citation for published version (APA): Mulvad, A. M. (2018). China’s Ideological Spectrum: A Two-dimensional Model of Elite Intellectuals’ Visions. Theory and Society, 47(5), 635–661. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-018-9326-6 Link to publication in CBS Research Portal General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us ([email protected]) providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 27. Sep. 2021 China’s Ideological Spectrum: A Two-dimensional Model of Elite Intellectuals’ Visions Andreas Møller Mulvad Journal article (Accepted version*) Please cite this article as: Mulvad, A. M. (2018). China’s Ideological Spectrum: A Two-dimensional Model of Elite Intellectuals’ Visions. Theory and Society, 47(5), 635–661. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-018-9326-6 This is a post-peer-review, pre-copyedit version of an article published in Theory and Society. The final authenticated version is available online at: DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-018-9326-6 * This version of the article has been accepted for publication and undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process, which may lead to differences between this version and the publisher’s final version AKA Version of Record. -

Mises and the Socialist Calculation Debate in China

This is a work in progress. 1 The (Im-)Possibility of Rational Socialism: Mises in China’s Market Reform Debate Isabella Weber, University of Massachusetts Amherst, [email protected] Abstract This paper investigates the long first decade of reform in China (1978-1992) to show that Mises, in particular his initiating contribution to the Socialist Calculation Debate, became relevant to the reconfiguration of China’s political economy when the reformers gave up on the late Maoist primacy of continuous revolution and adhered instead to an imperative of development and catching up. During the Cultural Revolution, Mao had rejected the notions of efficiency and rational economic management. In the late 1970s, the reformers under Deng Xiaoping’s leadership elevated these notions to highest principle. As a result, Mises’ critique that socialism could not achieve a rational economic order came to be debated throughout the 1980s and Chinese economists developed their own reading of Mises and the Socialist Calculation Debate. When Deng Xiaoping reinstated market reforms in the early 1990s after the Tiananmen crackdown, a history of thought review of the possibility of rational socialism and socialist markets helped to justify the Socialist Market Economy with Chinese Characteristics the official designation of China’s economic system to this day. Acknowledgements I would like to thank Liang Junshang for invaluable research assistance and my interview partners Jiang Chunze, Edwin Lim and Wu Jinglian. All remaining mistakes are my own. Keywords: Socialism; capitalism; market economy; Mises; China; comparative economic systems; This is a work in progress. 2 Introduction This essay traces the role of Ludwig Mises’ claim of the impossibility of rational socialism in China’s path-defining market reform debate (1978-1992).