Volume 9 Issue 7+8 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence Upon J. R. R. Tolkien

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2007 The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. Tolkien Kelvin Lee Massey University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Massey, Kelvin Lee, "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2007. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/238 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. David F. Goslee, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Thomas Heffernan, Michael Lofaro, Robert Bast Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled “The Roots of Middle-earth: William Morris’s Influence upon J. -

Zanesville & Western: a Creative Dissertation

ZANESVILLE & WESTERN: A CREATIVE DISSERTATION by Mark Allen Jenkins APPROVED BY SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: _________________________________________ Dr. Frederick Turner, Co-Chair _________________________________________ Dr. Charles Hatfield, Co-Chair _________________________________________ Dr. Matt Bondurant _________________________________________ Dr. Nils Roemer Copyright 2017 Mark Allen Jenkins All Rights Reserved ZANESVILLE & WESTERN A CREATIVE DISSERTATION by MARK ALLEN JENKINS, BA, MFA DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The University of Texas at Dallas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HUMANITIES – AESTHETIC STUDIES THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS May 2017 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are several significant people to thank in the development, creation, and refining of this dissertation, Zanesville & Western: A Creative Dissertation. Dr. Charles Hatfield supported me throughout the dissertation. His expertise on theoretical framing helped me develop an approach to my topic through a range of texts and disciplines. Dr. Frederick Turner encouraged me to continue and develop narrative elements in my poetry and took a particular interest when I began writing poems about southeastern Ohio. He encouraged me to get to the essence of specific poems through multiple drafts. Dr. Rainer Schulte, Dr. Richard Brettell, and Dr. Nils Roemer were my introduction to The University of Texas at Dallas. Dr. Schulte’s “Interdisciplinary Approaches to the Arts and Humanities” highlighted many of the strengths of our program, and “Crafting Poetry” provided useful insight into my own poetry as well as a thorough introduction international poetry. Dr. Brettell’s “Art and Anarchy” course expounded the idea that poets could be political in their lives and work, both overtly and implicitly. -

COSMOS + TAXIS | Volume 8 Issues 4 + 5 2020

ISSN 2291-5079 Vol 8 | Issue 4 + 5 2020 COSMOS + TAXIS Studies in Emergent Order and Organization Philosophy, the World, Life and the Law: In Honour of Susan Haack PART I INTRODUCTION PHILOSOPHY AND HOW WE GO ABOUT IT THE WORLD AND HOW WE UNDERSTAND IT COVER IMAGE Susan Haack on being awarded the COSMOS + TAXIS Ulysses Medal by University College Dublin Studies in Emergent Order and Organization Photo by Jason Clarke VOLUME 8 | ISSUE 4 + 5 2020 http: www.jasonclarkephotography.ie PHILOSOPHY, THE WORLD, LIFE AND EDITORIAL BOARDS THE LAW: IN HONOUR OF SUSAN HAACK HONORARY FOUNDING EDITORS EDITORS Joaquin Fuster David Emanuel Andersson* PART I University of California, Los Angeles (editor-in-chief) David F. Hardwick* National Sun Yat-sen University, The University of British Columbia Taiwan Lawrence Wai-Chung Lai William Butos University of Hong Kong (deputy editor) Foreword: “An Immense and Enduring Contribution” .............1 Trinity College Russell Brown Frederick Turner University of Texas at Dallas Laurent Dobuzinskis* Editor’s Preface ............................................2 (deputy editor) Simon Fraser University Mark Migotti Giovanni B. Grandi From There to Here: Fifty-Plus Years of Philosophy (deputy editor) with Susan Haack . 4 The University of British Columbia Mark Migotti Leslie Marsh* (managing editor) The University of British Columbia PHILOSOPHY AND HOW WE GO ABOUT IT Nathan Robert Cockram (assistant managing editor) Susan Haack’s Pragmatism as a The University of British Columbia Multi-faceted Philosophy ...................................38 Jaime Nubiola CONSULTING EDITORS Metaphysics, Religion, and Death Corey Abel Peter G. Klein or We’ll Always Have Paris ..................................48 Denver Baylor University Rosa Maria Mayorga Thierry Aimar Paul Lewis Naturalism, Innocent Realism and Haack’s Sciences Po Paris King’s College London subtle art of balancing Philosophy ...........................60 Nurit Alfasi Ted G. -

Margaret Dolinsky

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk 04 University of Plymouth Research Theses 01 Research Theses Main Collection 2014 FACING EXPERIENCE: A PAINTER'S CANVAS IN VIRTUAL REALITY Dolinsky, Margaret http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/3204 Plymouth University All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author's prior consent. FACING EXPERIENCE: A PAINTER’S CANVAS IN VIRTUAL REALITY by MARGARET DOLINSKY A thesis submitted to the University of Plymouth in partial fulfillment for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Art & Media Faculty of Arts In collaboration with Indiana University, Bloomington USA September 2014 Facing Experience: a painter's canvas in virtual reality Margaret Dolinsky Question: How can drawings and paintings created through a stream of consciousness methodology become a VR experience? Abstract This research investigate how shifts in perception might be brought about through the development of visual imagery created by the use of virtual environment technology. Through a discussion of historical uses of immersion in art, this thesis will explore how immersion functions and why immersion has been a goal for artists throughout history. -

In This Issue the Jones Team

The SGB Youth Literacy Letter Volume 5, Issue 1 Newsletter of the South Grey Bruce Youth Literacy Council March 2011 467 10th St, Suite 303 Hanover, ON N4N 1R3 The Jones Team In This Issue Hurray!!! Linette Jones has joined the Youth Literacy Welcome to the Letter H. In addition to news of Team as our Volunteer and Young Learner Coordinator. activities ongoing in our busy organization, we are She brings her positive presence and creativity to our happy to feature the contributions we received, from far office hub in supporting our volunteer tutor/learner and wide, nominating our Favourite Children`s Books. matches and intake. Linette works together with Dyan Read further for more exciting news! Jones in providing our Youth Literacy Program and Volunteer Network across our region, from Dundalk to We dedicate The Letter H to the Kincardine and up to Owen Sound. We are grateful for memory of the remarkable puppeteer, the generous support of the Ontario Trillium Foundation Jim Henson, creator of the Muppets. His insight and gentle philosophy for their two year grant sponsoring this staff growth. The have had a huge impact on innovative Jones Team is building the momentum of the learning approaches to learning. “My hope is to power of Youth Literacy! leave the world a little bit better than Our Volunteers Are Golden when I got here.” His head was We are proud of our Volunteers, those trained as tutors Kermit & Henson definitely linked to his heart. paired one-to-one with young learners in need of learning support, plus our volunteers who assist in Opening Hours for Youth Literacy Office managing our unique learning resources and facilitate Tuesday through Friday: 9 AM to 5 PM our vital fundraising activities. -

Frankfurt 2017 Rights List

Frankfurt 2017 Rights List Adult Rights List Frankfurt 2017 kt literary, llc. 9249 s. broadway, #200-543, highlands ranch, co 80129 720 344 4728 | ktliterary.com | [email protected] THE LAST SUN Book #1 in THE TAROT SEQUENCE by K.D. Edwards Pyr Books, April 2018 Edwards takes all the familiar pawns of Urban Fantasy and makes royalty of Cover them in his debut. We're invited into an alternative, historical world of coming soon staggering breadth and realization. The central characters, Rune and Brand, combine the loyalty of Frodo and Samwise with the sacrilege of a pairing like Tyrion and Bronn. When thrown in beside fascinating magical systems, breathtaking prose, and a relentless plot-- it's no wonder this novel puts previous stories of Atlantis to shame. – Scott Reintgen, author of NYXIA Decades ago, when Yuri Gagarin circled the planet in Vostok 1, something unimaginable happened. From that distance, he saw through the illusions that had kept Rune’s people hidden for millennia. He saw a massive island, in the northern Atlantic, where none should be. Atlantis. In the modern world -- and in the aftermath of the war that followed Atlantis’s revealing -- Atlanteans have resettled on the island of Nantucket, in a city built from extravagant global ruins. Rune Saint John is the son of a fallen Court, and the survivor of a brutal adolescent assault that remains one of New Atlantis’s most enduring mysteries. He and his Companion, Brand, operate on the edges of the city’s ruling class. An assignment from their benefactor, Lord Tower, will set them on a search for the kidnapped scion of an Arcana’s court. -

Shakespeare and His Contemporaries’ Graduate Conference 2009, 2010, 2011

The British Institute of Florence Proceedings of the ‘Shakespeare and His Contemporaries’ Graduate Conference 2009, 2010, 2011 Edited by Mark Roberts Volume I, Winter 2012 The British Institute of Florence Proceedings of the ‘Shakespeare and His Contemporaries’ Graduate Conference 2009, 2010, 2011 Edited by Mark Roberts Published by The British Institute of Florence Firenze, 2012 The British Institute of Florence Proceedings of the ‘Shakespeare and His Contemporaries’ Graduate Conference 2009, 2010, 2011 Edited by Mark Roberts Copyright © The British Institute of Florence 2012 The British Institute of Florence Palazzo Lanfredini, Lungarno Guicciardini 9, 50125 Firenze, Italia ISBN 978-88-907244-0-4 www.britishinstitute.it Tel +39 055 26778270 Registered charity no. 290647 Dedicated to Artemisia (b. 2012) Contents Foreword vii Preface ix 2009 The ‘demusicalisation’ of St Augustine’s tempus in Shakespeare’s tragedies 1 SIMONE ROVIDA Bardolatry in Restoration adaptations of Shakespeare 11 ENRICO SCARAVELLI 2010 Chaos in Arcadia: the politics of tragicomedy in Stuart pastoral theatre 19 SHEILA FRODELLA ‘The tragedy of a Jew’, the passion of a Merchant: shifting genres in a changing world 25 CHIARA LOMBARDI Shylock è un Gentleman! The Merchant of Venice, Henry Irving e l’Inghilterra Vittoriana 33 FRANCESCA MONTANINO 2011 ‘I wish this solemn mockery were o’er’: William Ireland’s ‘Shakespeare Forgeries’ 47 FRANCESCO CALANCA Giulietta come aporia: William Shakespeare e l’idea di Amore nel Platonismo del Rinascimento 55 CESARE CATÀ ‘Other’ translations -

Reclaiming Liberalism

PALGRAVE STUDIES IN CLASSICAL LIBERALISM SERIES EDITORS: DAVID F. HARDWICK · LESLIE MARSH Reclaiming Liberalism Edited by David F. Hardwick · Leslie Marsh [email protected] Palgrave Studies in Classical Liberalism Series Editors David F. Hardwick Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine The University of British Columbia Vancouver, BC, Canada Leslie Marsh Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine The University of British Columbia Vancouver, BC, Canada [email protected] This series offers a forum to writers concerned that the central presup- positions of the liberal tradition have been severely corroded, neglected, or misappropriated by overly rationalistic and constructivist approaches. The hardest-won achievement of the liberal tradition has been the wrestling of epistemic independence from overwhelming concentrations of power, monopolies and capricious zealotries. The very precondition of knowledge is the exploitation of the epistemic virtues accorded by soci- ety’s situated and distributed manifold of spontaneous orders, the DNA of the modern civil condition. With the confluence of interest in situated and distributed liberalism emanating from the Scottish tradition, Austrian and behavioral econom- ics, non-Cartesian philosophy and moral psychology, the editors are soliciting proposals that speak to this multidisciplinary constituency. Sole or joint authorship submissions are welcome as are edited collections, broadly theoretical or topical in nature. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/15722 -

Against Biopoetics: on the Use and Misuse of the Concept of Evolution in Contemporary Literary Theory

AGAINST BIOPOETICS: ON THE USE AND MISUSE OF THE CONCEPT OF EVOLUTION IN CONTEMPORARY LITERARY THEORY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English By Bradley Bankston B.A., New College, 1990 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1999 May 2004 Table of Contents Abstract................................................iii Introduction..............................................1 Part I: Evolutionary Psychology and Literary Theory......11 The Model...........................................11 The Critique........................................25 Evolutionary Psychology and Literary Theme..........56 Evolutionary Psychology and Literary Form...........77 Part 2: Evolutionary Progress and Literary Theory.......114 Biological Progress................................114 Complexity.........................................130 Self-Organization..................................149 Frederick Turner: Beauty and Evolution.............154 Alexander Argyros: Self-Organization, Complexity, and Literary Theory................................179 Conclusion..............................................215 Works Cited.............................................219 Vita....................................................230 ii Abstract This dissertation is a critical assessment of “biopoetics”: a new literary theory that attempts to import ideas from evolutionary science -

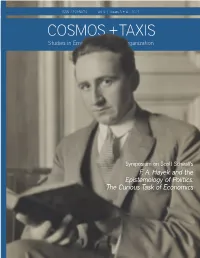

COSMOS + TAXIS | Volume 9 Issue 3+4 2021

ISSN 2291-5079 Vol 9 | Issues 3 + 4 2021 COSMOS + TAXIS Studies in Emergent Order and Organization Symposium on Scott Scheall's F. A. Hayek and the Epistemology of Politics: The Curious Task of Economics COVER IMAGE F. A. Hayek COSMOS + TAXIS Friedrich von Hayek: His Nobel Prize and Family Studies in Emergent Order and Organization Collection VOLUME 9 | ISSUES 3 + 4 2021 Sotheby's online auction, March 2019. EDITORIAL BOARDS HONORARY FOUNDING EDITORS EDITORS SYMPOSIUM ON SCOTT SCHEALL'S Joaquin Fuster Leslie Marsh* F. A. HAYEK AND THE EPISTEMOLOGY University of California, Los Angeles (editor-in-chief) David F. Hardwick* The University of British Columbia OF POLITICS: THE CURIOUS TASK OF The University of British Columbia William N. Butos Lawrence Wai-Chung Lai (deputy editor) ECONOMICS University of Hong Kong Trinity College Frederick Turner Laurent Dobuzinskis* University of Texas at Dallas (deputy editor) Simon Fraser University Editorial Introduction ....................................1 Giovanni B. Grandi William N. Butos (deputy editor) The University of British Columbia Symposium Prologue ................................... 2 Nathan Robert Cockeram (assistant editor) Scott Scheall The University of British Columbia Epistemics and Economics, Political Economy CONSULTING EDITORS and Social Philosophy ..................................9 Thierry Aimar Ted G. Lewis Peter Boettke Sciences Po Paris Technology Assessment Group, Nurit Alfasi Salinas Ben Gurion University of the Negev Joseph Isaac Lifshitz The Political Process: Experimentation -

The Green in White Noise: Consumption, Technology, and The

The Green in White Noise: Consumption, Technology, and the Environment by Katelyn Hummer A thesis presented for the B.A. degree with Honors in The Department of English University of Michigan Winter 2013 © March 25, 2013 Katelyn Ashley Hummer Acknowledgements To all voices of encouragement forming the panasonic halo that compelled a silent pen: though I will refrain from including pages of names, please know that you are my signifieds, my referents—my rock. Words cannot express the depth of my gratitude. Abstract In this thesis, I examine consumption in White Noise from two aspects: the characters’ motivations to consume and, subsequently, the ecological consequences of this consumption. Through this discussion of consumption, I propose a re- thinking of White Noise’s canonical status as a postmodern novel, suggesting that perhaps it is a pioneer of a post-postmodern genre. Chapter One begins with an exploration of why it may be “natural” for Jack and Babette to want to consume, which reveals that the they consume to viscerally remain detached from their inanimate environment, ultimately allowing them to “conquer” death. However, the characters’ unnatural, over-consumption results in a state of being too detached; and this feeling of disconnection renders their consumption unfulfilling because they feel an ambiguous lack of a concrete something. This feeling of lack results in a desire for an attachment to something real and tangible in a world of commodities and simulacra, which I propose entails a return to “ancient” “tribal” values. But, in Chapter Two, I show that a sense of telos can also satiate this desire for existential attachment. -

Transactions of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society

TRANSACTIONS MASSACHUSETTS HORTICULTURAL SOCIETY FOR THE YEARS 1843-4-5-6 TO WHICH IS ADDED THE ADDRESS DELIVERED BEFORE THE SOCIETY ON 15TH MAY, 1845, AT THE DEDICATION OF THEIR HALL. BOSTON: DUTTON AND WENTWORTH'S PRINT 1847. {,52 .OG CHAPEL i B^ At a meeting of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, on the 25th day of October, 1S45, " Voted, That Messrs. Samuel Walker, Joseph Breck, Henry W. Dut- TON, Charles K. Dillaway, and Ebenezer Wight, be a Committee to pub- lish the Transactions of the Society for 1S43-4-5-6, to which shall be added the Address delivered before the Society at the dedication of their Hall." The Committee have attended to the duty assigned to them by the above vote, to which they have added, the Act of Incorporation of the Massachusetts Horti- cultural Society, passed June 12th, 1829 ; also, an Additional Act, passed Febru- ary 5th, 1344, and a part of an Act, incorporating the proprietors of Mount Auburn Cemetery, with a List of the Members of the Society, and a Catalogue of the Books in the Library. All which is respectfully submitted. By order of the Committee, SAMUEL WALKER, Chairman. Boston, February 23, 1847. ACT OF INCORPORATION. (KommonUjealti) of li^assacijusetts In the Year of Our Lord One Thousand Eight Hundred and Twenty-nine. AN ACT TO INCORPORATE THE MASSACHUSETTS HORTICULTURAL SOCIETY. Section 1. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives in General Court assembled, and by the authority of the same : That Zebedee Cook, Jr., Robert L. Emmons, William Worthington, B. V.