Biotechnology and Biosafety Biotechnology and Biosafety

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central Valley & Highlands

© Lonely Planet Publications 124 lonelyplanet.com ALAJUELA & THE NORTH OF THE VALLEY 125 History exhibit, trout lake and the world’s largest butterfly Central Valley & Of the 20 or so tribes that inhabited pre- enclosure. Hispanic Costa Rica, it is thought that the Monumento National Arqueológico Guayabo Central Valley Huetar Indians were the most ( p160 ) The country’s only significant archaeological site Highlands dominant. But there is very little historical isn’t quite as impressive as anything found in Mexico or evidence from this period, save for the ar- Guatemala, but the rickety outline of forest-encompassed cheological site at Guayabo. Tropical rains villages will still spark your inner Indiana Jones. Parque Nacional Tapantí-Macizo Cerro de la The rolling verdant valleys of Costa Rica’s midlands have traditionally only been witnessed and ruthless colonization have erased most of pre-Columbian Costa Rica from the pages Muerte ( p155 ) This park receives more rainfall than during travelers’ pit stops on their way to the country’s more established destinations. The of history. any other part of the country, so it is full of life. Jaguars, area has always been famous for being one of the globe’s major coffee-growing regions, In 1561 the Spanish pitched their first ocelots and tapirs are some of the more exciting species. CENTRAL VALLEY & and every journey involves twisting and turning through lush swooping terrain with infinite permanent settlement at Garcimuñoz, in Parque Nacional Volcán Irazú ( p151 ) One of the few lookouts on earth that affords views of both the Caribbean HIGHLANDS coffee fields on either side. -

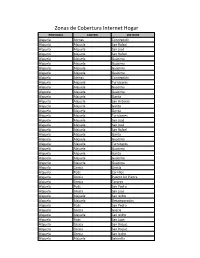

Zonas De Cobertura Internet Hogar

Zonas de Cobertura Internet Hogar PROVINCIA CANTON DISTRITO Alajuela Atenas Concepción Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Atenas Concepción Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela San Antonio Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Poás Carrillos Alajuela Grecia Puente De Piedra Alajuela Grecia Tacares Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia San José Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Desamparados Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Poás San Juan Alajuela Grecia San Roque Alajuela Grecia San Roque Alajuela Grecia San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Sabanilla Alajuela Alajuela Tambor Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Carrizal Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Carrizal Alajuela Alajuela Tambor Alajuela Grecia Bolivar Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Grecia San Jose Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Grecia Tacares Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia Tacares -

Agua Caliente, Espacialidad Y Arquitectura En Una Comunidad Nucleada Antigua De Costa Rica

31 Cuadernos de Antropología No.19, 31-55, 2009 AGUA CALIENTE, ESPACIALIDAD Y ARQUITECTURA EN UNA COMUNIDAD NUCLEADA ANTIGUA DE COSTA RICA Jeffrey Peytrequín Gómez* RESUMEN En este artículo se presentan las particularidades de un sitio arqueológi- co ubicado en el Valle Central Oriental de Costa Rica, Agua Caliente de Cartago (C-35AC). Alrededor del 600 d.C., esta comunidad se constituyó en un centro político-ideológico con un ordenamiento espacial que permitió el despliegue de diversas actividades; dichas actividades son el reflejo de relaciones sociales a nivel cacical. En Agua Caliente se erigieron varias es- tructuras habitacionales, así como muros de contención de aguas, calzadas y vastos cementerios. Además, todas estas manifestaciones arquitectónicas comparten un tipo de construcción específico. De tal manera, la cultura material recuperada apunta a Agua Caliente como un espacio significativo dentro de la dinámica cultural de esta región de Costa Rica. Palabras claves: Arquitectura, técnicas constructivas, montículos, calza- das, dique. ABSTRACT This article explores the architectural specificities of Agua Caliente de Car- tago (C-35AC), an archaeological site located in the Costa Rica’s central area. This community, circa 600 A.D., was an ideological-political center with a spatial distribution that permitted diverse activities to take place. These practices reflect rank social relations at a chiefdom level. Several dwelling structures were at Agua Caliente, as were stone wall dams, paved streets and huge cemeteries. These constructions shared particular charac- teristics. The material culture suggests that this site was a significant space in the regional culture. Keywords: Architecture, building techniques, mounds, causeways, dam. * Jeffrey Peytrequín Gómez. -

Libro ING CAC1-36:Maquetación 1.Qxd

© Enrique Montesinos, 2013 © Sobre la presente edición: Organización Deportiva Centroamericana y del Caribe (Odecabe) Edición y diseño general: Enrique Montesinos Diseño de cubierta: Jorge Reyes Reyes Composición y diseño computadorizado: Gerardo Daumont y Yoel A. Tejeda Pérez Textos en inglés: Servicios Especializados de Traducción e Interpretación del Deporte (Setidep), INDER, Cuba Fotos: Reproducidas de las fuentes bibliográficas, Periódico Granma, Fernando Neris. Los elementos que componen este volumen pueden ser reproducidos de forma parcial siem- pre que se haga mención de su fuente de origen. Se agradece cualquier contribución encaminada a completar los datos aquí recogidos, o a la rectificación de alguno de ellos. Diríjala al correo [email protected] ÍNDICE / INDEX PRESENTACIÓN/ 1978: Medellín, Colombia / 77 FEATURING/ VII 1982: La Habana, Cuba / 83 1986: Santiago de los Caballeros, A MANERA DE PRÓLOGO / República Dominicana / 89 AS A PROLOGUE / IX 1990: Ciudad México, México / 95 1993: Ponce, Puerto Rico / 101 INTRODUCCIÓN / 1998: Maracaibo, Venezuela / 107 INTRODUCTION / XI 2002: San Salvador, El Salvador / 113 2006: Cartagena de Indias, I PARTE: ANTECEDENTES Colombia / 119 Y DESARROLLO / 2010: Mayagüez, Puerto Rico / 125 I PART: BACKGROUNG AND DEVELOPMENT / 1 II PARTE: LOS GANADORES DE MEDALLAS / Pasos iniciales / Initial steps / 1 II PART: THE MEDALS WINNERS 1926: La primera cita / / 131 1926: The first rendezvous / 5 1930: La Habana, Cuba / 11 Por deportes y pruebas / 132 1935: San Salvador, Atletismo / Athletics -

Orchidaceae: Pleurothallidinae) from Costa Rica in the P

LANKESTERIANA 17(2): 153—164. 2017. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15517/lank.v17i2.29850 TWO NEW SPECIES OF PLEUROTHALLIS (ORCHIDACEAE: PLEUROTHALLIDINAE) FROM COSTA RICA IN THE P. PHYLLOCARDIA GROUP FRANCO PUPULIN1–3,5, MELISSA DÍAZ-MORALES1, MELANIA FERNÁNDEZ1,4 & JAIME AGUILAR1 1 Lankester Botanical Garden, University of Costa Rica. P.O. Box 302-7050 Cartago, Costa Rica 2 Harvard University Herbaria, 22 Divinity Avenue, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, U.S.A. 3 Marie Selby Botanical Gardens, 811 South Palm Avenue, Sarasota, Florida 34236, U.S.A. 4 Department of Plant & Soil Science, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas 79409, U.S.A. 5 Author for correspondence: [email protected] ABSTRACT. Two new species of Pleurothallis subsection Macrophyllae-Fasciculatae from Costa Rica are described and illustrated, and their relationships discussed. Pleurothallis pudica, from the central Pacific mountain region, is compared with P. phyllocardia, but it is easily recognized by the densely pubescent- hirsute flowers. Pleurothallis luna-crescens, from the Caribbean slope of the Talamanca chain, is compared with P. radula and P. rectipetala, from which it is distinguished by the dark purple flowers and the distinctly longer, dentate petals, respectively. A key to the species of the group in Costa Rica and western Panama is presented. KEY WORDS: flora of Costa Rica, new species, Pleurothallidinae,Pleurothallis phyllocardia group Introduction. The species of Pleurothallis R.Br. can be distinguished. Even excluding the group that close to Humboltia cordata Ruiz & Pavón (1978) [= Wilson and collaborators (2011, 2013) characterized as Pleurothallis cordata (Ruiz & Pav.) Lindl.] represent the “Mesoamerican clade” of Pleurothallis, consisting one of the largest groups of taxa within the genus (Luer of fairly small plants and mostly non-resupinate flowers 2005). -

Derived Flood Assessment

30 July 2021 PRELIMINARY SATELLITE- DERIVED FLOOD ASSESSMENT Alajuela Limon, Cartago, Heredia and Alajuela Provinces, Costa Rica Status: Several areas impacted by flooding including agricultural areas and road infrastructure. Increased water levels also observed along rivers. Further action(s): continue monitoring COSTA RICA AREA OF INTEREST (AOI) 30 July 2021 PROVINCE AOI 6, Los Chiles AOI 5, Sarapiqui AOI 3, Matina AOI 2, Limon AOI 4, Turrialba AOI 1, Talamanca N FLOODS OVER COSTA RICA 70 km NICARAGUA AOI 6, Los Chiles Satellite detected water as of 29 July 2021 AOI 5, Sarapiqui AOI 3, Matina Canton AOI 2, Limon City AOI 4, Turrialba Caribbean Sea North Pacific Ocean AOI 1, Talamanca Legend Province boundary International boundary Area of interest Cloud mask Reference water PANAMA Satellite detected water as of 29 July 2021 [Joint ABI/VIIRS] Background: ESRI Basemap 3 Image center: AOI 1: Talamanca District, Limon Province 82°43'56.174"W Limon Province 9°34'12.232"N Flood tracks along the Sixaola river observed BEFORE AFTER COSTA RICA Flood track COSTA RICA Flood track Sixaola river Sixaola river PANAMA PANAMA Sentinel-2 / 19 June 2021 Sentinel-2 / 29 July 2021 4 Image center: AOI 2: Limon City, Limon District, Limon Province 83°2'54.168"W Limon Province 9°59'5.985"N Floods and potentially affected structures observed BEFORE AFTER Limon City Limon City Potentially affected structures Evidence of drainage Increased water along the irrigation canal N N 400 400 m m Sentinel-2 / 19 June 2021 Sentinel-2 / 29 July 2021 5 Image center: AOI -

Neotectónica De Las Fallas Ochomogo Y Capellades Y Su Relación Con El Sistema De Falla Aguacaliente, Falda Sur Macizo Irazú-Turrialba, Costa Rica

Revista Geológica de América Central, 48: 119-139, 2013 ISSN: 0256-7024 NEOTECTÓNICA DE LAS FALLAS OCHOMOGO Y CAPELLADES Y SU RELACIÓN CON EL SISTEMA DE FALLA AGUACALIENTE, FALDA SUR MACIZO IRAZÚ-TURRIALBA, COSTA RICA NEOTECTONICS OF THE OCHOMOGO AND CAPELLADES FAULTS AND ITS RELATION WITH THE AGUACALIENTE FAULT SYSTEM, SOUTHERN SLOPES OF THE IRAZÚ-TURRIALBA MASSIF, COSTA RICA Walter Montero1*, Wilfredo Rojas1, 2 & Lepolt Linkimer1, 2 1Centro de Investigaciones en Ciencias Geológicas, Universidad de Costa Rica, Apdo. 11501-2060, Ciudad Universitaria Rodrigo Facio, Costa Rica 2Escuela Centroamericana de Geología, Universidad de Costa Rica, Apdo. 214-2060, Ciudad Universitaria Rodrigo Facio, Costa Rica *Autor para contacto: [email protected] (Recibido: 26/3/2012; aceptado: 11/6/2012) ABSTRACT: Geomorphic studies supplemented with geological information allow us to define the predominantly left-lateral strike-slip Capellades and Ochomogo faults. The Capellades fault connects with the Aguacaliente fault through the Cartago transpressive zone, including E-W folds and oblique (reverse-left lateral) faults. The Ochomogo fault is located between south San José and the southern slopes of the Irazú Volcano, is about 22 km long, and has a nearly left lateral strike slip along its E-W trend to an oblique (normal-left-lateral) slip along its ENE trending part. The interaction between the Ochomogo and Aguacaliente faults results in a transtensional regime that formed the Coris and Guarco valleys. The Capellades fault trends ENE to NE, is about 25 km long, and is located in the southern and southeastern slopes of the Irazú and Turrialba volcanoes. Several geomorphic features show between few meters to 0.67 km of left-lateral displacements along the Capellades fault trace. -

Amenazas De Origen Natural Cantón De Turrialba

AMENAZAS DE ORIGEN NATURAL CANTÓN DE TURRIALBA AMENAZAS HIDROMETEOROLÓGICAS DEL CANTÓN DE TURRIALBA El Cantón de Turrialba posee una red fluvial bien definida, la misma cuenta con un conjunto de ríos y quebradas que son el punto focal de las amenazas hidrometeorológicas del cantón, dicha red de drenaje está compuesta principalmente por los ríos: Turrialba, Colorado, Aquiares, Reventazón, Tuis, Pacuare, Atirro, Guayabo y las quebradas Poró, Gamboa, El Túnel y La Leona en La Suiza. De estos ríos y quebradas algunos, han disminuido el período de recurrencia de inundaciones a un año, o incluso a períodos menores, lo anterior por causa de la ocupación de las planicies de inundación, y el desarrollo urbano en forma desordenada y sin ninguna planificación, y al margen de las leyes de desarrollo urbano y Forestal. Así mismo, el lanzado de desechos sólidos a los cauces, a redundando en la reducción de la capacidad de la sección hidráulica, lo que provoca el desbordamiento de ríos y quebradas. Situación empeorada por los serios problemas de construcción de viviendas cercanas a los ríos en el cantón de Turrialba. Las zonas o barrios más afectados y alto riesgo por las inundaciones de los ríos y quebradas antes mencionadas son: La Alegría, Mon Río, La Margot, San Rafael, Turrialba Centro, Dominica, Pastor, Alto Cruz, Guaria, Repasto, Isabel, Aquiares, Tuis, La Suiza, Canadá, Leona, Esperanza, Atirro, Guayabo, Poró, San Cayetano y Américas. Recomendaciones. Debido a que el mayor problema que generan las inundaciones, es por la ocupación de las planicies de inundación de los ríos, con asentamientos formales e informales, la deforestación de las cuencas altas y medias, la falta de programas de uso sostenible de recursos naturales se recomienda que: 1. -

Thursday, April 16, 2015

collegiate/elite/high school division thursday, april 16, 2015 historic hilmer lodge stadium mt. san antonio college walnut, california THURSDAY; APRIL 16, 2015 RUNNING EVENT SCHEDULE TIME EVENT# GENDER EVENT SECTION 6:00 PM 110 M 3,000M Steeplechase C 6:11 PM 111 M 3,000M Steeplechase B 6:22 PM 210 W 3,000M Steeplechase C 6:35 PM 211 W 3,000M Steeplechase B 6:48 PM 212 W 3000M Steeplechase A 7:01 PM 112 M 3,000M Steeplechase A thursday running events running thursday 7:15 PM 121 M 10,000M A 7:45 PM 221 W 10,000M A 8:27 PM 222 W 10,000M INV B 9:04 PM 223 W 10,000M INV A 9:46 PM 122 M 10,000M INV B 10:16 PM 123 M 10,000M INV A 10:44 PM 120 M 10,000M B 11:15 PM 220 W 10,000M B DISCLAIMER: AN ATHLETES/TEAMS HEAT AND LANE (within an event#) ARE SUBJECT TO CHANGE. Changes may occur due to scratches, verification of marks, etc. At the Mt. SAC Relays we try our best to create fair, equitable and exciting FULL FIELD races. We thank you for your cooperation. UPDATED ON APRIL 15, 2015 @ 10:00 PM Mt. San Antonio College Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 9:53 PM 4/15/2015 Page 1 57th ANNUAL MT. SAC RELAYS "Where the world's best athletes compete" Hilmer Lodge Stadium, Walnut, California - 4/16/2015 to 4/18/2015 Meet Program - Thursday Track Event 110 Men's 3000 Meter Steeplechase C C/O Event 111 Men's 3000 Meter Steeplechase B C/O Thursday 4/16/2015 - 6:00 PM Thursday 4/16/2015 - 6:11 PM World Record: 7:53.63 2004 Saif Shaheen World Record: 7:53.63 2004 Saif Shaheen American Rec: 8:04.71 2014 Evan Jager American Rec: 8:04.71 2014 Evan Jager Meet Record: 8:26.14 -

Farmers' Perceptions of Trees on Their Land in the Santa Cruz Area, Biological Corridor Volcanica Central-Talamanca, Costa

Lucile Chamayou Exam Number 111391 September 2011 Farmers’ perceptions of trees on their land in the Santa Cruz area, Biological Corridor Volcanica Central-Talamanca, Costa Rica MSc Conservation and Rural Development Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology School of Anthropology and Conservation University of Kent Canterbury, UK DICE - September 2011 Farmers’ perceptions of trees on their land in the Santa Cruz area, Biological Corridor Volcanica Central-Talamanca, Costa Rica Lucile Chamayou Abstract The Biological Corridor Volcanica Central-Talamanca aims to restore and maintain the biological connectivity between protected areas in Costa Rica. Trees outside forest such as live fences, dispersed trees within pastures and riparian areas, play productive and conservation roles and increase connectivity in the agricultural landscapes. The study aims to explore farmers’ perceptions of trees on their land in the Santa Cruz area, north-west of the biological corridor. Semi-structured interviews with key informants and farmers were conducted. Farmers maintained trees outside forest on their land and attributed diverse values to trees including technical, through the provision of live fences or shelter for cattle, economic, as a source of timber, fuelwood or fruits, and ecological, for wildlife and watershed protection but also social, cultural, aesthetic and heritage values. They reported limitations to have trees such as lack of capital, labour and land and lack of adapted species and technical assistance. More investigations are needed especially on the relation between tree cover and landscape functional connectivity. Still, local authorities and organisations including the BCVCT’s committee should ensure and encourage trees outside forest uses in the agricultural landscape through a strategic planning including the promotion of the conversion of fences to live fences, farmers training and education, technical assistance and the adaptation of existing incentives such as Payments for Ecosystem Services. -

(CCC-O) VII COSTA RICAN ORIENTEERING CHAMPIONSHIP “INTERNATIONAL” November 22-25, 2018 TURRIALBA COSTA RICA BULLETIN Nº 2

III CENTRAL AMERICAN AND CARIBBEAN ORIENTEERING CHAMPIONSHIP (CCC-O) VII COSTA RICAN ORIENTEERING CHAMPIONSHIP “INTERNATIONAL” November 22-25, 2018 TURRIALBA COSTA RICA BULLETIN Nº 2 CONTENIDO Pág. GREETINGS .......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 ABOUT TURRIALBA .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 ORGANIZING COMMITTEE ................................................................................................................................................... 4 GENERAL INFORMATION: .................................................................................................................................................... 4 IOF EVENT ADVISER ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 PROGRAM ........................................................................................................................................................................... 5 CONTROL SYSTEM ............................................................................................................................................................... 5 CATEGORIES ....................................................................................................................................................................... -

El Valle De Orosi, Explorado Por Alexander Von Frantzius

80 El valle de Orosi, explorado por Alexander von Frantzius El valle de Orosi, explorado por Alexander von Frantzius Luko Hilje Quirós Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza (CATIE). Costa Rica. [email protected] Recibido: 14 -V-08 / Aceptado: 04-VI-08 Resumen En este texto, además de transcribirse completo el artí- culo El antiguo convento de la misión de Orosi en Cartago de Costa Rica, publicado de manera anónima en 1860 en la revista alemana Das Ausland, se demuestra que su au- tor fue el naturalista alemán Alexander von Frantzius, y no su colega Karl Hoffmann. Además, se hace una inter- pretación -mediante numerosas notas al pie de página- de varios aspectos de su contenido, relacionados con temas de historia natural, etnografía e historia. Abstract Orosi’s valley, explored by Alexander von Frantzius Figura 1. Alexander von Frantzius PALABRAS CLAVE: Ritt Alexander von Frantzius, Luko Hilje Quirós Alemania, Misión de Orosi, Besides entirely transcribing the article The old con- Cartago, Costa Rica, convento franciscano, botánica, zoología, vent of the Orosi Mission in Cartago, Costa Rica, which historia natural, etnia bribri. was anonymously published in 1860 in the German mag- azine Das Ausland, it is demonstrated that its author was KEY WORDS: Alexander von Frantzius, a German naturalist, and not Alexander von Frantzius, his colleague Karl Hoffmann. In addition, through many Germany, Orosi Mission, footnotes, an interpretation is made of several aspects of Cartago, Costa Rica, Franciscan its contents dealing with natural history, ethnography convent, botany, zoology, nat- and history. ural history, Bribri ethnic group. Revista Comunicación. Volumen 17, año 29, No.