Making Space for Better Forestry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central Valley & Highlands

© Lonely Planet Publications 124 lonelyplanet.com ALAJUELA & THE NORTH OF THE VALLEY 125 History exhibit, trout lake and the world’s largest butterfly Central Valley & Of the 20 or so tribes that inhabited pre- enclosure. Hispanic Costa Rica, it is thought that the Monumento National Arqueológico Guayabo Central Valley Huetar Indians were the most ( p160 ) The country’s only significant archaeological site Highlands dominant. But there is very little historical isn’t quite as impressive as anything found in Mexico or evidence from this period, save for the ar- Guatemala, but the rickety outline of forest-encompassed cheological site at Guayabo. Tropical rains villages will still spark your inner Indiana Jones. Parque Nacional Tapantí-Macizo Cerro de la The rolling verdant valleys of Costa Rica’s midlands have traditionally only been witnessed and ruthless colonization have erased most of pre-Columbian Costa Rica from the pages Muerte ( p155 ) This park receives more rainfall than during travelers’ pit stops on their way to the country’s more established destinations. The of history. any other part of the country, so it is full of life. Jaguars, area has always been famous for being one of the globe’s major coffee-growing regions, In 1561 the Spanish pitched their first ocelots and tapirs are some of the more exciting species. CENTRAL VALLEY & and every journey involves twisting and turning through lush swooping terrain with infinite permanent settlement at Garcimuñoz, in Parque Nacional Volcán Irazú ( p151 ) One of the few lookouts on earth that affords views of both the Caribbean HIGHLANDS coffee fields on either side. -

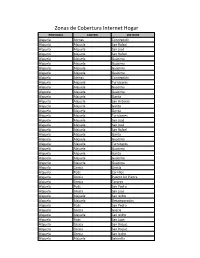

Zonas De Cobertura Internet Hogar

Zonas de Cobertura Internet Hogar PROVINCIA CANTON DISTRITO Alajuela Atenas Concepción Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Atenas Concepción Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela San Antonio Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Poás Carrillos Alajuela Grecia Puente De Piedra Alajuela Grecia Tacares Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia San José Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Desamparados Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Poás San Juan Alajuela Grecia San Roque Alajuela Grecia San Roque Alajuela Grecia San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Sabanilla Alajuela Alajuela Tambor Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Carrizal Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Carrizal Alajuela Alajuela Tambor Alajuela Grecia Bolivar Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Grecia San Jose Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Grecia Tacares Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia Tacares -

The Chocó-Darién Conservation Corridor

July 4, 2011 The Chocó-Darién Conservation Corridor A Project Design Note for Validation to Climate, Community, and Biodiversity (CCB) Standards (2nd Edition). CCB Project Design Document – July 4, 2011 Executive Summary Colombia is home to over 10% of the world’s plant and animal species despite covering just 0.7% of the planet’s surface, and has more registered species of birds and amphibians than any other country in the world. Along Colombia’s northwest border with Panama lies the Darién region, one of the most diverse ecosystems of the American tropics, a recognized biodiversity hotspot, and home to two UNESCO Natural World Heritage sites. The spectacular rainforests of the Darien shelter populations of endangered species such as the jaguar, spider monkey, wild dog, and peregrine falcon, as well as numerous rare species that exist nowhere else on the planet. The Darién is also home to a diverse group of Afro-Colombian, indigenous, and mestizo communities who depend on these natural resources. On August 1, 2005, the Council of Afro-Colombian Communities of the Tolo River Basin (COCOMASUR) was awarded collective land title to over 13,465 hectares of rainforest in the Serranía del Darién in the municipality of Acandí, Chocó in recognition of their traditional lifestyles and longstanding presence in the region. If they are to preserve the forests and their traditional way of life, these communities must overcome considerable challenges. During 2001- 2010 alone, over 10% of the natural forest cover of the surrounding region was converted to pasture for cattle ranching or cleared to support unsustainable agricultural practices. -

Agua Caliente, Espacialidad Y Arquitectura En Una Comunidad Nucleada Antigua De Costa Rica

31 Cuadernos de Antropología No.19, 31-55, 2009 AGUA CALIENTE, ESPACIALIDAD Y ARQUITECTURA EN UNA COMUNIDAD NUCLEADA ANTIGUA DE COSTA RICA Jeffrey Peytrequín Gómez* RESUMEN En este artículo se presentan las particularidades de un sitio arqueológi- co ubicado en el Valle Central Oriental de Costa Rica, Agua Caliente de Cartago (C-35AC). Alrededor del 600 d.C., esta comunidad se constituyó en un centro político-ideológico con un ordenamiento espacial que permitió el despliegue de diversas actividades; dichas actividades son el reflejo de relaciones sociales a nivel cacical. En Agua Caliente se erigieron varias es- tructuras habitacionales, así como muros de contención de aguas, calzadas y vastos cementerios. Además, todas estas manifestaciones arquitectónicas comparten un tipo de construcción específico. De tal manera, la cultura material recuperada apunta a Agua Caliente como un espacio significativo dentro de la dinámica cultural de esta región de Costa Rica. Palabras claves: Arquitectura, técnicas constructivas, montículos, calza- das, dique. ABSTRACT This article explores the architectural specificities of Agua Caliente de Car- tago (C-35AC), an archaeological site located in the Costa Rica’s central area. This community, circa 600 A.D., was an ideological-political center with a spatial distribution that permitted diverse activities to take place. These practices reflect rank social relations at a chiefdom level. Several dwelling structures were at Agua Caliente, as were stone wall dams, paved streets and huge cemeteries. These constructions shared particular charac- teristics. The material culture suggests that this site was a significant space in the regional culture. Keywords: Architecture, building techniques, mounds, causeways, dam. * Jeffrey Peytrequín Gómez. -

Pachira Aquatica, (Zapotón, Pumpo)

How to Grow a Sacred Maya Flower Pachira aquatica, (Zapotón, Pumpo) Nicholas Hellmuth 1 Introduction: There are several thousand species of flowering plants in Guatemala. Actually there are several thousand flowering TREES in Guatemala. If you count all the bushes, shrubs, and vines, you add thousands more. Then count the grasses, water plants; that’s a lot of flowers to look at. Actually, if you count the orchids in Guatemala you would run out of numbers! Yet out of these “zillions” of beautiful tropical flowers, the Classic Maya, for thousands of years, picture less than 30 different species. It would be a challenge to find representations of a significant number of orchids in Maya art: strange, since they are beautiful, and there are orchids throughout the Maya homeland as well as in the Olmec homeland, plus orchids are common in the Izapa area of proto_Maya habitation in Chiapas. Yet other flowers are pictured in Maya yart, yet in the first 150 years of Maya studies, only one single solitary flower species was focused on: the sacred water lily flower! (I know this focus well, I wrote my PhD dissertation featuring this water lily). But already already 47 years ago, I had noticed flowers on Maya vases: there were several vases that I discovered myself in a royal burial at Tikal that pictured stylized 4-petaled flowers (Burial 196, the Tomb of the Jade Jaguar). Still, if you have XY-thousand flowers blooming around you, why did the Maya picture less than 30? In other words, why did the Maya select the water lily as their #1 flower? I know most of the reasons, but the point is, the Maya had XY-thousand. -

Stand Growth Scenarios for Bombacopsis Quinata Plantations In

Forest Ecology and Management 174 (2003) 345–352 Stand growth scenarios for Bombacopsis quinata plantations in Costa Rica Luis Diego Pe´rez Corderoa,b,1, Markku Kanninenc,*, Luis Alberto Ugalde Ariasd,2 aAgreement Centro Agrono´mico Tropical de Investigacio´n y Ensen˜anza (CATIE), Turrialba, Costa Rica bUniversity of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland cCentro Agrono´mico Tropical de Investigacio´n y Ensen˜anza (CATIE), Research Program, 7170 Turrialba, Costa Rica dPlantation Silviculture, CATIE, Turrialba, Costa Rica Abstract In total 60 plots of approximately 80 trees each (including missing trees) were measured, with ages between 1 and 26 years. The main objective of this study was to develop intensive management scenarios for B. quinata plantations in Costa Rica to ensure high yielding of timber wood. The scenarios were based on a fitted curve for the relationship of DBH, and total height with age. A criterion of maximum basal area (18, 20, 22 and 24 m2 haÀ1) was used to simulate different site qualities. Plantation density was modeled as a function of the crown area occupation of the standing trees. The scenarios consist of rotation periods between 23 and 30 years, final densities of 100–120 trees haÀ1, mean DBH between 46 and 56 cm, and mean total heights of 30–35 m. The productivity at the end of the rotation varies between 9.6 and 11.3 m3 haÀ1 per year, yielding a total volume at the end of the rotation of 220–340 m3 haÀ1. The scenarios presented here may provide farmers and private companies with useful and realistic growth projections for B. -

Orchidaceae: Pleurothallidinae) from Costa Rica in the P

LANKESTERIANA 17(2): 153—164. 2017. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15517/lank.v17i2.29850 TWO NEW SPECIES OF PLEUROTHALLIS (ORCHIDACEAE: PLEUROTHALLIDINAE) FROM COSTA RICA IN THE P. PHYLLOCARDIA GROUP FRANCO PUPULIN1–3,5, MELISSA DÍAZ-MORALES1, MELANIA FERNÁNDEZ1,4 & JAIME AGUILAR1 1 Lankester Botanical Garden, University of Costa Rica. P.O. Box 302-7050 Cartago, Costa Rica 2 Harvard University Herbaria, 22 Divinity Avenue, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, U.S.A. 3 Marie Selby Botanical Gardens, 811 South Palm Avenue, Sarasota, Florida 34236, U.S.A. 4 Department of Plant & Soil Science, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas 79409, U.S.A. 5 Author for correspondence: [email protected] ABSTRACT. Two new species of Pleurothallis subsection Macrophyllae-Fasciculatae from Costa Rica are described and illustrated, and their relationships discussed. Pleurothallis pudica, from the central Pacific mountain region, is compared with P. phyllocardia, but it is easily recognized by the densely pubescent- hirsute flowers. Pleurothallis luna-crescens, from the Caribbean slope of the Talamanca chain, is compared with P. radula and P. rectipetala, from which it is distinguished by the dark purple flowers and the distinctly longer, dentate petals, respectively. A key to the species of the group in Costa Rica and western Panama is presented. KEY WORDS: flora of Costa Rica, new species, Pleurothallidinae,Pleurothallis phyllocardia group Introduction. The species of Pleurothallis R.Br. can be distinguished. Even excluding the group that close to Humboltia cordata Ruiz & Pavón (1978) [= Wilson and collaborators (2011, 2013) characterized as Pleurothallis cordata (Ruiz & Pav.) Lindl.] represent the “Mesoamerican clade” of Pleurothallis, consisting one of the largest groups of taxa within the genus (Luer of fairly small plants and mostly non-resupinate flowers 2005). -

Bombacopsis Quinata Family: Bombacaceae Pochote

Bombacopsis quinata Family: Bombacaceae Pochote Other Common Names: Cedro espino (Honduras, Nicaragua), Saquisaqui (Venezuela), Ceiba tolua (Colombia). Distribution: Common in the more open forests of western Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama. Also on the Atlantic side of Panama and in Colombia and Venezuela. Abundant throughout its range, mostly on well-drained, often gravelly soils on the upper slopes of low hills and ridges. The Tree: Medium-sized to large tree, not infrequently 3 ft and sometimes 5 or 6 ft. in diameter; reaches a height of 100 ft. Wide-spreading crown of heavy branches; somewhat irregular bole; generally buttressed. Trunk and larger branches armed with hard sharp prickles. The Wood: General Characteristics: Heartwood is uniform pale pinkish or pinkish brown when freshly cut, becoming light to dark reddish brown on exposure; sharply demarcated from yellowish sapwood. Grain straight to slightly interlocked; texture medium; luster rather low. Heartwood without distinctive odor but sometimes with a slightly astringent taste. Weight: Basic specific gravity (ovendry weight/green volume) averages 0.45. Air-dry density about 34 pcf. Mechanical Properties: (2-in. standard) Moisture content Bending strength Modulus of elasticity Maximum crushing strength (%) (Psi) (1,000 psi) (Psi) Green (74) 7,560 1,260 3,440 12% 10,490 1,400 5,660 12% (71) 12,110 NA 6,480 Janka side hardness 650 lb for green material and 720 lb for dry. Forest Products Laboratory toughness average for green and dry material is 103 in.-lb (5/8-in. specimen). Drying and Shrinkage: Air-seasons very slowly, required almost a year to dry 8/4 stock to a moisture content of 20%. -

Derived Flood Assessment

30 July 2021 PRELIMINARY SATELLITE- DERIVED FLOOD ASSESSMENT Alajuela Limon, Cartago, Heredia and Alajuela Provinces, Costa Rica Status: Several areas impacted by flooding including agricultural areas and road infrastructure. Increased water levels also observed along rivers. Further action(s): continue monitoring COSTA RICA AREA OF INTEREST (AOI) 30 July 2021 PROVINCE AOI 6, Los Chiles AOI 5, Sarapiqui AOI 3, Matina AOI 2, Limon AOI 4, Turrialba AOI 1, Talamanca N FLOODS OVER COSTA RICA 70 km NICARAGUA AOI 6, Los Chiles Satellite detected water as of 29 July 2021 AOI 5, Sarapiqui AOI 3, Matina Canton AOI 2, Limon City AOI 4, Turrialba Caribbean Sea North Pacific Ocean AOI 1, Talamanca Legend Province boundary International boundary Area of interest Cloud mask Reference water PANAMA Satellite detected water as of 29 July 2021 [Joint ABI/VIIRS] Background: ESRI Basemap 3 Image center: AOI 1: Talamanca District, Limon Province 82°43'56.174"W Limon Province 9°34'12.232"N Flood tracks along the Sixaola river observed BEFORE AFTER COSTA RICA Flood track COSTA RICA Flood track Sixaola river Sixaola river PANAMA PANAMA Sentinel-2 / 19 June 2021 Sentinel-2 / 29 July 2021 4 Image center: AOI 2: Limon City, Limon District, Limon Province 83°2'54.168"W Limon Province 9°59'5.985"N Floods and potentially affected structures observed BEFORE AFTER Limon City Limon City Potentially affected structures Evidence of drainage Increased water along the irrigation canal N N 400 400 m m Sentinel-2 / 19 June 2021 Sentinel-2 / 29 July 2021 5 Image center: AOI -

Neotectónica De Las Fallas Ochomogo Y Capellades Y Su Relación Con El Sistema De Falla Aguacaliente, Falda Sur Macizo Irazú-Turrialba, Costa Rica

Revista Geológica de América Central, 48: 119-139, 2013 ISSN: 0256-7024 NEOTECTÓNICA DE LAS FALLAS OCHOMOGO Y CAPELLADES Y SU RELACIÓN CON EL SISTEMA DE FALLA AGUACALIENTE, FALDA SUR MACIZO IRAZÚ-TURRIALBA, COSTA RICA NEOTECTONICS OF THE OCHOMOGO AND CAPELLADES FAULTS AND ITS RELATION WITH THE AGUACALIENTE FAULT SYSTEM, SOUTHERN SLOPES OF THE IRAZÚ-TURRIALBA MASSIF, COSTA RICA Walter Montero1*, Wilfredo Rojas1, 2 & Lepolt Linkimer1, 2 1Centro de Investigaciones en Ciencias Geológicas, Universidad de Costa Rica, Apdo. 11501-2060, Ciudad Universitaria Rodrigo Facio, Costa Rica 2Escuela Centroamericana de Geología, Universidad de Costa Rica, Apdo. 214-2060, Ciudad Universitaria Rodrigo Facio, Costa Rica *Autor para contacto: [email protected] (Recibido: 26/3/2012; aceptado: 11/6/2012) ABSTRACT: Geomorphic studies supplemented with geological information allow us to define the predominantly left-lateral strike-slip Capellades and Ochomogo faults. The Capellades fault connects with the Aguacaliente fault through the Cartago transpressive zone, including E-W folds and oblique (reverse-left lateral) faults. The Ochomogo fault is located between south San José and the southern slopes of the Irazú Volcano, is about 22 km long, and has a nearly left lateral strike slip along its E-W trend to an oblique (normal-left-lateral) slip along its ENE trending part. The interaction between the Ochomogo and Aguacaliente faults results in a transtensional regime that formed the Coris and Guarco valleys. The Capellades fault trends ENE to NE, is about 25 km long, and is located in the southern and southeastern slopes of the Irazú and Turrialba volcanoes. Several geomorphic features show between few meters to 0.67 km of left-lateral displacements along the Capellades fault trace. -

Volcanic Activity in Costa Rica in 2012 Official Annual Summary

Volcanic Activity in Costa Rica in 2012 Official Annual Summary Turrialba volcano on January 18 th , 2012: central photo, the 2012 vent presents flamme due to the combustion of highly oxidant magmatic gas (photo: J.Pacheco). On the right, ash emission by the 2012 vent at 4:30am the same day (photo: G.Avard).On the left, incandescence is visible since then (photo: G.Avard 2-2-2012, 8pm). Geoffroy Avard, Javier Pacheco, María Martínez, Rodolfo van der Laat, Efraín Menjivar, Enrique Hernández, Tomás Marino, Wendy Sáenz, Jorge Brenes, Alejandro Aguero, Jackeline Soto, Jesus Martínez Observatorio Vulcanológico y Sismológico de Costa Rica OVSICORI-UNA 1 I_ Introduction At 8:42 a.m. on September 5 th , 2012, a Mw = 7.6 earthquake occurred 20 km south of Samara, Peninsula de Nicoya, Guanacaste. The maximum displacement was 2.5 m with a maximum vertical motion about 60 cm at Playa Sa Juanillo (OVSICORI Report on September 11 th , 2012). The fault displacement continued until the end of September through postseismic motions, slow earthquakes, viscoelastic response and aftershocks (> 2500 during the first 10 days following the Nicoya earthquake). The seismicity spread to most of the country (Fig.1) Figure 1: Seismicity in September 2012 and location of the main volcanoes. Yellow star: epicenter of the Nicoya seism on September 5 th , 2012 (Mw = 7.6). White arrow: direction of the displacement due to the Nicoya seism (map: Walter Jiménez Urrutia, Evelyn Núñez, y Floribeth Vega del grupo de sismología del OVSICORI-UNA). Regarding the volcanoes, the seism of Nicoya generated an important seismic activity especially in the volcanic complexes Irazú-Turrialba and Poás as well as an unusual seismic activity mainly for Miravalles, Tenorio and Platanar-Porvenir. -

(Aves: Turdidae) Distribution, First Record in Barva Volcano, Costa Rica

BRENESIA 73-74: 138-140-, 2010 Filling the gap of Turdus nigrescens (Aves: Turdidae) distribution, first record in Barva Volcano, Costa Rica Luis Sandoval1 & Melania Fernández1,2 1. Escuela de Biología, Universidad de Costa Rica. 2060. Costa Rica. [email protected] 2. Jardín Botánico Lankester, Cartago, Costa Rica. (Received: October 22, 2009) KEY WORDS. Sooty Thrush, Barva Volcano, new distribution The Sooty Thrush (Turdus nigrescens) is an glacial periods (Pleistocene epoch) the lowest endemic bird species from Costa Rica and western limit of highland vegetation descended, creating Panama highlands (Ridgely & Gwynne Jr.1989, a continuous belt of suitable habitat for highland Stiles & Skutch 1989). It inhabits open areas, forest birds between Central Volcanic and Talamanca edges and páramo in the Central Volcanic and mountain ranges (Barrantes in press). This Talamanca mountain ranges above 2500 m (Stiles likely allowed birds to move between these two & Skutch 1989, Garrigues & Dean 2007). The mountains ranges. Although evidence of the Central Volcanic mountain range represents an presence of Sooty Thrush in Barva Volcano during east-west oriented row of about 80 km of volcanic this period lacks, the presence of other highland cones, formed by Poás (2708 m), Barva (2900 m), bird species with similar habitat requirements Irazú (3432 m) and Turrialba (3340 m) volcanoes of those of the Sooty Thrush (e.g, Catharus (Alvarado-Induni 2000). gracilirostris, Pezopetes capitalis and Basileuterus This robin is very abundant along all its range melanogenys) in the area suggests that this species distribution, but it has not been previously reported likely also occurred in this massif (Wolf 1976, Stiles in the Barva Volcano, a volcanic massif in the & Skutch 1989, Barrantes 2005, Chavarria 2006, Central Volcanic mountain range (Chavarría 2006, Garrigues & Dean 2007).