Stylistic Changes of Pompeian Floor Mosaics Sharon Wussow College of Dupage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pompeii and Herculaneum: a Sourcebook Allows Readers to Form a Richer and More Diverse Picture of Urban Life on the Bay of Naples

POMPEII AND HERCULANEUM The original edition of Pompeii: A Sourcebook was a crucial resource for students of the site. Now updated to include material from Herculaneum, the neighbouring town also buried in the eruption of Vesuvius, Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook allows readers to form a richer and more diverse picture of urban life on the Bay of Naples. Focusing upon inscriptions and ancient texts, it translates and sets into context a representative sample of the huge range of source material uncovered in these towns. From the labels on wine jars to scribbled insults, and from advertisements for gladiatorial contests to love poetry, the individual chapters explore the early history of Pompeii and Herculaneum, their destruction, leisure pursuits, politics, commerce, religion, the family and society. Information about Pompeii and Herculaneum from authors based in Rome is included, but the great majority of sources come from the cities themselves, written by their ordinary inhabitants – men and women, citizens and slaves. Incorporating the latest research and finds from the two cities and enhanced with more photographs, maps and plans, Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook offers an invaluable resource for anyone studying or visiting the sites. Alison E. Cooley is Reader in Classics and Ancient History at the University of Warwick. Her recent publications include Pompeii. An Archaeological Site History (2003), a translation, edition and commentary of the Res Gestae Divi Augusti (2009), and The Cambridge Manual of Latin Epigraphy (2012). M.G.L. Cooley teaches Classics and is Head of Scholars at Warwick School. He is Chairman and General Editor of the LACTOR sourcebooks, and has edited three volumes in the series: The Age of Augustus (2003), Cicero’s Consulship Campaign (2009) and Tiberius to Nero (2011). -

Roman Art: Pompeii and Herculaneum

Roman Art: Pompeii and Herculaneum August 24, 79 AD A Real City with Real People: The Everyday Roads & Stepping Stones Thermopolia …hot food stands Pistrina Pistrina = bakery Aerial view of the forum (looking northeast), Pompeii, Italy, second century BCE and later. (1) forum, (2) Temple of Jupiter (Capitolium), (3) basilica. The Forum Aerial view of the amphitheater, Pompeii, Italy, ca. 70 BCE. Brawl in the Pompeii amphitheater, wall painting from House I,3,23, Pompeii, Italy, ca. 60–79 CE. Fresco, 5’ 7” x 6’ 1”. Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples. Pompeii was surrounded by a wall about 2 miles long Outside the Wall • Pompeians buried their dead outside the city wall. Inside the Walls • Buildings are packed close together Houses Restored view and plan of a typical Roman house of the Late Republic and Early Empire (John Burge). (1) fauces, (2) atrium, (3) impluvium, (4) cubiculum, (5) ala, (6) tablinum, (7) triclinium, (8) peristyle. Floor Plan – Villa of the Mysteries • The main entrance often included mosaics “CAVE CANEM” House of the Tragic Poet Atrium An atrium had a compluvium and an impluvium What was the purpose of these features? Purposes: • Collect rain water • Allow light to come in Reconstruction of the atrium at the Villa of the Faun Peristyles (court yards) House of the Vettii Villa of the Mysteries Wall Paintings • Generally, elaborate paintings covered the walls of every room Studious Girl, Fresco from a Pompeii Home. Not a portrait of an individual. Its purpose is too show that the inhabitants of the house were literate and cultured people. The Four Pompeian Styles • Division = Based on differences in treatment of wall and painted space First Pompeian Style • began 2nd century BCE • Goal: imitate expensive marble House of Sallust Samnite House, Herculaneum Second Pompeian Style • Began early 1st century BCE • Goal: create a 3D world on a 2D surface Villa of the Mysteries (oecus – banquet hall) Dionysiac mystery frieze, Second Style wall paintings in Room 5 of the Villa of the Mysteries, Pompeii, Italy, ca. -

Revenge of the BH-SAT Edited by Jacob Reed Packet 12 Tossups 1

Bulldog High School Academic Tournament 2017 (XXVI): Revenge of the BH-SAT Written by Yale Student Academic Competitions (Stephen Eltinge, Adam Fine, Isaac Kirk-Davidoff, Moses Kitakule, Laurence Li, Jacob Reed, Mark Torres, James Wedgwood, Cathy Xue, and Bo You), Jason Golfinos, and Clare Keenan Edited by Jacob Reed Packet 12 Tossups 1. For a body undergoing circular motion due to gravity, total energy equals potential energy times this factor. In special relativity, length contraction is proportional “one minus beta-squared” all raised to this power. The reduced mass of a pair of identical bodies equals this number times the mass of one body. For a solid disk in the x-y plane, the moments of inertia about the x and y axes both equal (*) this constant times the moment of inertia about the z axis. This fraction appears in the potential energy formula for a harmonic oscillator, and it multiplies “a t-squared” in the acceleration term for projectile motion. Kinetic energy equals—for 10 points—what fraction, times mass times velocity-squared? ANSWER: one half [or one over two; or 0.5] <AF> 2. Warning: description acceptable. One of these places in Sri Lanka includes a room framed by long elephant tusks and is located in Kandy. Most of these places in Japan follow the Shichido Garan, a floorplan that mimics the structure of the human body, placing the butsuden at the heart and the hojo outside of the body. One of these places called Ryoanji, has a (*) garden consisting entirely of 15 rocks. These places often have stupas in the form of pagodas. -

Marble, Memory, and Meaning in the Four Pompeian Styles of Wall Painting

MARBLE, MEMORY, AND MEANING IN THE FOUR POMPEIAN STYLES OF WALL PAINTING by Lynley J. McAlpine A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Art and Archaeology) in the University of Michigan 2014 Doctoral Committee: Professor Elaine K. Gazda, Chair Professor Lisa Nevett Professor David Potter Professor Nicola Terrenato Emeritus Professor Norman Yoffee The difference between false memories and true ones is the same as for jewels: it is always the false ones that look the most real, the most brilliant. Salvador Dalí, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí © Lynley McAlpine All Rights Reserved 2013 Acknowledgements This project would have been impossible without the guidance of my advisor and dissertation chair, Elaine Gazda, who has provided unflagging support for all aspects of my work. I am grateful to have been able to work under the supervision of someone who I consider a model for the kind of scholar I hope to become: one who has a keen critical eye and who values collaboration and innovation. I have also benefited greatly from the sensible advice of Lisa Nevett, who has always helped me to recognize the possibilities and limitations of my approaches and evidence. David Potter’s perspective has been indispensable in determining how literary and historical sources could be employed responsibly in a study that focuses mainly on material culture. Nicola Terrenato has encouraged me to develop a critical and rigorous approach, and his scholarship has been an important model for my own. Finally, Norman Yoffee has been a continual source of advice and guidance, while opening my eyes to the ways my research can reach across disciplinary boundaries. -

Greek Artists and Their Colors (Apart from Ceramics) J.L

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Greek Color Theory and the Four Elements Art July 2000 Chapter 4: Greek artists and their colors (apart from ceramics) J.L. Benson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgc Benson, J.L., "Chapter 4: Greek artists and their colors (apart from ceramics)" (2000). Greek Color Theory and the Four Elements. 8. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgc/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Greek Color Theory and the Four Elements by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IV. GREEK ARTISTS AND THEIR COLORS (APART FROM CERAMICS) GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS The larger history of concepts embedded in the Four Elements/Four Colors theory, as worked out in this study, seems capable of illuminating a kind of inner driving force throughout the drama of Greek spirituality. To be sure, the well-preserved ceramic tradition alone provided the visual framework for this (at a level not concerned with the great variations in artistic quality characteristic of the category—in modern terms we might say at the existential level of the artisan process). But ceramics, of course, is not the whole story of color. Textiles, statues, paintings, architecture all exhibited color and we must try to take this into account, even though in many cases the color is largely gone. Obviously it is not easy to make judgments about faded bits of color. -

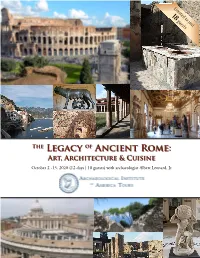

The Legacy of Ancient Rome: Art, Architecture & Cuisine October 2 -13, 2020 (12 Days | 18 Guests) with Archaeologist Albert Leonard, Jr

Limited to just Limited to just 18 18 travelers guests © Derbrauni The Legacy of Ancient Rome: Art, Architecture & Cuisine October 2 -13, 2020 (12 days | 18 guests) with archaeologist Albert Leonard, Jr. Dear Traveler, Next October, when the weather is typically perfect, discover the glorious legacy of ancient Rome with the AIA’s Dr. Al Leonard, recipient of many awards and a popular AIA Tours lecturer and host. With expert local guides plus a professional tour manager to handle all of the logistics, you can relax and immerse yourself in learning and experiencing ancient and Renaissance art and architecture, including numerous UNESCO World Heritage sites. Enjoy delicious food and wine, and excellent, 4-star hotels, perfectly located for exploring on your own during free time: five nights in central Rome, two nights in Naples overlooking the Bay of Naples, and three nights in Amalfi overlooking the Tyrrhenian Sea. © Carla Tavares Highlights are many and include: • The Roman Forum, with a private visit to the Temple of Antoninus and Faustina; and special entry to the Colosseum's upper levels; • Stunning paintings and mosaics at the House of Augustus on the Palatine Hill; • The Capitoline Museums, with their magnificent Classical and Renaissance art; • Outstanding Renaissance sculptures and paintings at the Borghese Gallery; • A day trip to Tivoli for visits to Hadrian’s Villa, a 2nd-century A.D. complex; and Villa d’Este, a superb Renaissance palace. • Breakfast within the Vatican Museums, before entering the Sistine Chapel © Intel Free -

From Palaces to Pompeii: the Architectural and Social Context of Hellenistic Floor Mosaics in the House of the Faun Alexis M

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 From Palaces to Pompeii: The Architectural and Social Context of Hellenistic Floor Mosaics in the House of the Faun Alexis M. Christensen Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES FROM PALACES TO POMPEII: THE ARCHITECTURAL AND SOCIAL CONTEXT OF HELLENISTIC FLOOR MOSAICS IN THE HOUSE OF THE FAUN By ALEXIS M. CHRISTENSEN A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Classics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2006 Copyright © 2006 Alexis M. Christensen All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Alexis M. Christensen defended on June 30, 2006. _________________________________ Nancy T. de Grummond Professor Directing Dissertation _________________________________ Marcia Rosal Outside Committee Member _________________________________ Daniel J. Pullen Committee Member _________________________________ David Stone Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii This dissertation is dedicated to the memory of my grandmothers. M. Jane Grubb, 1921-1994 and Fonda I. Christensen, 1925-2005. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In the course of writing my dissertation and indeed throughout my academic career I have received no greater support and encouragement than that which I received from my parents and professors. I can think of no more fitting words of gratitude than those of Vitruvius: Itaque ego maximas infinitasque parentibus ago atque habeo gratias, probantes me arte erudiendum curaverunt, et ea, quae non potest esse probata sine litteratura encyclioque doctrinarum omnium disciplina. -

Understanding the Lived Experience of Ancient Roman Gardens Devlin F

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2019 Understanding the Lived Experience of Ancient Roman Gardens Devlin F. Daley Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, and the Other Classics Commons Recommended Citation Daley, Devlin F., "Understanding the Lived Experience of Ancient Roman Gardens" (2019). Honors Theses. 2283. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/2283 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Understanding the Lived Experience of Ancient Roman Gardens By Devlin Daley ********* Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of Classics UNION COLLEGE March 2019 ABSTRACT DALEY, DEVLIN: Understanding the Lived Experience of Ancient Roman Gardens ADVISOR: Angela Commito My research takes a psychologically influenced approach to the study of archaeological remains to explore the experiential nature of ancient gardens in the Roman domus and villa of the Campania region of southern Italy. I argue that significant factors of spatial and social theory drove the intended experience in space and in the curated environment of the garden. I focus on the architecture of these spaces, such as peristyles and reflecting pools, from which walking paths and movement through space can be reconstructed. I also dive into understanding the remains of horticulture, including different plants and trees that would have grown naturally or been planted by the owner of the home for either pleasure or production. -

Mureddu, N.; 'The Gorgon and the Cross: Rereading

Mureddu, N.; ‘The Gorgon and the Cross: Rereading the Alexander Mosaic and the House of the Faun at Pompeii’ Rosetta 17: 52 – 71 http://www.rosetta.bham.ac.uk/issue17/mureddu.pdf The Gorgon and the Cross: Rereading the Alexander Mosaic and the House of the Faun at Pompeii Nicola Mureddu Abstract: The House of the Faun is one of the most intriguing buildings in Pompeii. Its striking feature is the presence of several mosaics decorating the whole house, the most representative of which is perhaps the well-known Alexander Mosaic. This new study analyses the interpretation not only of the Alexander Mosaic, but of the whole set decorating the House of the Faun, by considering and comparing with the possible esoteric creeds of the late Hellenism. In the study I suggest that instead of being simply decorative features of a wealthy Samnite, the mosaics are actually linked to each other by a philosophical pattern linked with an unclear esoteric circle, related with either the Heracliteans or the Hermetics. 52 1. The Mosaic and its subject The mosaic of Alexander, found at the House of the Faun at Pompeii is one of the most intriguing representations of an ancient battle (figure 1)1. We no longer possess the original painting from which it was probably copied. Whether the original was completely identical to its transposition in stone or just a model bearing different details in comparison with the mosaic we will never know. The scene preserved by Vesuvius’ lava shows a battle identified as one of the three battles Alexander fought against Darius III Codomannus between 334 and 331 BC.2 Badian thinks he can recognize the last battle, Arbela (or Gaugamela) in the image showed by the mosaic, pointing out that both armies seem to be using Macedonian sarissae, which, according to Diodoros,3 were used only at Gaugamela.4 FIGURE 1: THE ALEXANDER MOSAIC, MUSEO ARCHEOLOGICO NAZIONALE DI NAPOLI, PARTICULAR. -

The Alexander Mosaic and the House of Faun (Pompeii

THE ALEXANDER MOSAIC AND THE HOUSE OF THE FAUN (POMPEII VI 12, 1-8) GEOMETRY PROPORTIONS AND ART OF COMPOSITION FERRO Luisa (IT) Abstract. This text analyzes the celebrated Alexander Mosaic, found in the House of the Faun in Pompeii starting from the premise that it may hide the traces of a compositional process based on rules that built its origin, the Ground Zero of any work of art as such. A painstaking process of calculation and precision based on regulators, even surprising symmetries, and aesthetic precision in the placement of figures that projects the represented scene in a well-defined, memorable, self- sufficient and “representational” form. Finally the text analyses the relationship between mosaic and the composition process of the House. Keywords: geometry and art, composition, Alexander Mosaic Pompeii Mathematic Subject Classification: Primary 01A20 1 The Gran Mosaico On October 24, 1831, a surprising discovery was made in the so-called Domus of the Faun. The mosaic found at the center of a room with two red columns entered through a Nilotic- themed threshold was clearly “of a quite eminent value ... And its style and execution are finer than any other similar work from the ancient times, including the five other works discovered in the same house and described in the press. 9 pl. wide and 19 ½ long, this large mosaic made of tiny tesserae of colorful marbles depicts a battle between Greeks and Barbarians”. [9] While other mosaics had actually been found in the house – apparently belonging to the same figurative scheme [29] and made of tiny tesserae – the Alexander Mosaic was immediately recognized for its exceptional value [18] [19] [24]: “.. -

YEAR 12 ANCIENT History Anne Gripton & Peter Roberts

YEAR 12 ANCIENT History Anne Gripton & Peter Roberts Free-to-download sample pages with answers Book 1 Ancient History.indb 1 18/1/19 5:18 pm 1 - Core StudY Chapter Cities of Vesuvius Pompeii Herculaneumand Agriculture was the cash crop and intensive farming was Introduction evidenced everywhere, even on small garden plots inside the city walls. ›› The volcanic eruption of 79 CE was a disaster for the ÎÎ inhabitants of Pompeii and Herculaneum but the volcano The processing of agricultural products is evidenced in did more than take thousands of lives: it sealed the cities many small workshops in Pompeii. Pompeii was an under a layer of ash and lava, thereby preserving the remains important industrial and trading centre and port according of two vibrant, prosperous Roman towns. By methodical to Strabo, as well as a resort for wealthy Romans. This study of the ruins and artefacts of these sites, historians attracted Roman investment as they enjoyed the climate and archaeologists have been able to gain a unique and magnificent sea views. glimpse into life in a Roman town, and by extension the ÎÎPompeii city is an oval shape and rests on a prehistoric Empire, as it was lived nearly 2000 years ago. lava flow. The city walls followed the path of the lava flow. Pompeii covers 66 hectares and about three quarters of the site is currently excavated. SURVEY ÎÎPompeii was completely covered and hermetically sealed THE GEOGRAPHICAL SETTING AND by a seven-metre layer of volcanic ash, lapilli (rock NATURAL FEATURES OF CAMPANIA fragments) and pumice (heavy rock) from Vesuvius in 79 CE. -

Domestic Art Versus Domestic Archaeology a Consideration of the Types of Evidence from Roman Campania

Anistoriton Journal, vol. 12 (2010-2011) Art 1 Domestic Art versus Domestic Archaeology A consideration of the types of evidence from Roman Campania The inspiration for this paper has come from a series of ideas and issues that have resulted from considering the use of artistic evidence for the designation of room function. This has previously been discussed in numerous studies, but the primary focus that is intended within this paper is to contemplate how various types of archaeological and artistic evidence are used for interpreting the function of domestic space in the Roman World. In order to keep the primary focus upon methods used for the consideration of ancient evidence, the examples used in this discussion have been taken from three residences in Roman Campania (the House of the Faun, the Villas of Fannius Synistor and the Mysteries), which assists in limiting the issue of temporal, contextual and cultural variance. This should allow for a greater focus upon the methodology that is used to reflect upon the way in which ancient art is interpreted. It should be noted that the interpretation of art is inherently subjective, but the primary focus for this paper is upon how ancient art is used as a source of evidence for our understanding of classical cultures. The primary concern of this paper is to examine how ancient art is interpreted, in order to advocate a holistic approach for the modern scholar. While disciplinary separation and integrity is a common feature of modern academic life, it can sometimes become a hindrance for a complete analysis of an ancient artefact, architectural space or artistic piece.