The Impact of Societal Changes on Developments in Roman Mosaics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Greece and Rome

Spartan soldier HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHY Ancient Greece and Rome Reader Amphora Alexander the Great Julius Caesar Caesar Augustus THIS BOOK IS THE PROPERTY OF: STATE Book No. PROVINCE Enter information COUNTY in spaces to the left as PARISH instructed. SCHOOL DISTRICT OTHER CONDITION Year ISSUED TO Used ISSUED RETURNED PUPILS to whom this textbook is issued must not write on any page or mark any part of it in any way, consumable textbooks excepted. 1. Teachers should see that the pupil’s name is clearly written in ink in the spaces above in every book issued. 2. The following terms should be used in recording the condition of the book: New; Good; Fair; Poor; Bad. Ancient Greece and Rome Reader Creative Commons Licensing This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. You are free: to Share—to copy, distribute, and transmit the work to Remix—to adapt the work Under the following conditions: Attribution—You must attribute the work in the following manner: This work is based on an original work of the Core Knowledge® Foundation (www.coreknowledge.org) made available through licensing under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This does not in any way imply that the Core Knowledge Foundation endorses this work. Noncommercial—You may not use this work for commercial purposes. Share Alike—If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license to this one. With the understanding that: For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. -

Perspective and Geometry in the Roman Painted Gardens

ISSN: 2687-8402 DOI: 10.33552/OAJAA.2019.02.000527 Open Access Journal of Archaeology and Anthropology Review Article Copyright © All rights are reserved by Manuela Piscitelli Perspective and Geometry in the Roman Painted Gardens Manuela Piscitelli* Università degli Studi della Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, Department of Architecture and Industrial Design, Italy *Corresponding author: Manuela Piscitelli, Università degli Studi della Campania Received Date: November 18, 2019 Luigi Vanvitelli, Department of Architecture and Industrial Design, Via San Lorenzo ad Septimum, Aversa (CE), Italy. Published Date: November 25, 2019 Abstract Garden painting is a very precise genre that is distinct from landscape painting. Present in Roman villas but also in tombs of the same period, wall to obtain an illusory effect of expansion of space, responds to precise geometric characteristics. The article relates the structure, also geometric, it responds to some specific compositional rules. The structure of the representation, realized for the most part with the intent to break through the by the point of view under which the garden (real or imaginary) must be observed, and in both cases, there is a will to bend nature within rigidly of the Roman gardens with their pictorial representation, which derives from it its justification. In both cases, in fact, the composition is guided betweengeometric the and parts. symmetrical schemas. The sense of perspective recreated in the painted gardens offers at first glance a feeling of naturalness into the garden, which -

Political Crisis in Rhetorical Exercises of the Early Roman Empire Shunichiro Yoshida the University of Tokyo

ISSN: 2519-1268 Issue 2 (Spring 2017), pp. 39-50 DOI: 10.6667/interface.2.2017.34 Political Crisis in Rhetorical Exercises of the Early Roman Empire SHUNICHIRO YOSHIDA The University of Tokyo Abstract The ancient Romans experienced a great political crisis in the first century B. C. They fought many civil wars, which ended the republic and led to the establishment of the empire. The nature of these civil wars and the new regime was a politically very sensitive question for the next generation and could not be treated in a direct manner. In this paper I shall examine how literature in this age dealt with this sensitive problem. Special attention will be paid on declamations (rhetorical exercises on fictitious themes), which discussed repeatedly themes concerned with political crises such as domestic discord or rule of a tyrant. Keywords: Latin Oratory, Rhetorical Training, Early Roman Empire, Roman Politics © 2017 Shunichiro Yoshida This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. http://interface.ntu.edu.tw/ 39 Political Crisis in Rhetorical Exercises of the Early Roman Empire 1. Politics in Rome in the 1st Century B.C. Rome experienced its greatest political change in the 1st century B.C. Since the latter half of the previous century, its Republican system, which was established in the late 6th century B.C. according to the tradition, proved to contain serious problems. This led to repeated fierce civil wars in Rome. In the middle of the 1st century B.C., Caesar fought against Pompey and other members of the senatorial nobility who tried to defend the traditional system and defeated them completely. -

The Nature of Hellenistic Domestic Sculpture in Its Cultural and Spatial Contexts

THE NATURE OF HELLENISTIC DOMESTIC SCULPTURE IN ITS CULTURAL AND SPATIAL CONTEXTS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Craig I. Hardiman, B.Comm., B.A., M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Dr. Mark D. Fullerton, Advisor Dr. Timothy J. McNiven _______________________________ Advisor Dr. Stephen V. Tracy Graduate Program in the History of Art Copyright by Craig I. Hardiman 2005 ABSTRACT This dissertation marks the first synthetic and contextual analysis of domestic sculpture for the whole of the Hellenistic period (323 BCE – 31 BCE). Prior to this study, Hellenistic domestic sculpture had been examined from a broadly literary perspective or had been the focus of smaller regional or site-specific studies. Rather than taking any one approach, this dissertation examines both the literary testimonia and the material record in order to develop as full a picture as possible for the location, function and meaning(s) of these pieces. The study begins with a reconsideration of the literary evidence. The testimonia deal chiefly with the residences of the Hellenistic kings and their conspicuous displays of wealth in the most public rooms in the home, namely courtyards and dining rooms. Following this, the material evidence from the Greek mainland and Asia Minor is considered. The general evidence supports the literary testimonia’s location for these sculptures. In addition, several individual examples offer insights into the sophistication of domestic decorative programs among the Greeks, something usually associated with the Romans. -

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

The Ptolemies: an Unloved and Unknown Dynasty. Contributions to a Different Perspective and Approach

THE PTOLEMIES: AN UNLOVED AND UNKNOWN DYNASTY. CONTRIBUTIONS TO A DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVE AND APPROACH JOSÉ DAS CANDEIAS SALES Universidade Aberta. Centro de História (University of Lisbon). Abstract: The fifteen Ptolemies that sat on the throne of Egypt between 305 B.C. (the date of assumption of basileia by Ptolemy I) and 30 B.C. (death of Cleopatra VII) are in most cases little known and, even in its most recognised bibliography, their work has been somewhat overlooked, unappreciated. Although boisterous and sometimes unloved, with the tumultuous and dissolute lives, their unbridled and unrepressed ambitions, the intrigues, the betrayals, the fratricides and the crimes that the members of this dynasty encouraged and practiced, the Ptolemies changed the Egyptian life in some aspects and were responsible for the last Pharaonic monuments which were left us, some of them still considered true masterpieces of Egyptian greatness. The Ptolemaic Period was indeed a paradoxical moment in the History of ancient Egypt, as it was with a genetically foreign dynasty (traditions, language, religion and culture) that the country, with its capital in Alexandria, met a considerable economic prosperity, a significant political and military power and an intense intellectual activity, and finally became part of the world and Mediterranean culture. The fifteen Ptolemies that succeeded to the throne of Egypt between 305 B.C. (date of assumption of basileia by Ptolemy I) and 30 B.C. (death of Cleopatra VII), after Alexander’s death and the division of his empire, are, in most cases, very poorly understood by the public and even in the literature on the topic. -

Ennius Or Cicero? the Disreputable Diviners at Cic

ACTA CLASSICAXLIV(200/) 153-166 ISSN 0065-1141 ENNIUS OR CICERO? THE DISREPUTABLE DIVINERS AT CIC. DE DIV. 1.132 A.T. Nice University of the Witwatersrand ABSTRACT At the end of the first book of Cicero's De Divir1atior1e, Quintus remarks that, even though he believes in divination, there are some diviners whom he would not trust to give accurate predictions. These comments are followed by a quotation from Ennius' Telamo. Most modem scholars have assumed, therefore, that the previous lines also contain an echo, if not a paraphrase of Ennius' work. This supposition does not seem to be supported by the language or style employed by Cicero. The lines should rather be understood as embodying the parochial view that elite Romans had towards forms of divination that were foreign, rustic or mercenary and not practised by the Roman state. I At the end of the first book of De Divinatione ( 1.132), Quintus completes his argument in favour of divination by denying the respectability of certain kinds ofdiviners: Nunc illa testabor, non me sortilegos neque eos, qui quaestus causa hariolentur, ne psychomantia quidem, quibus Appius, amicus tuus, uti solebat, agnoscere; non habeo denique nauci Marsum augurem, non vicanos haruspices, non de circo astrologos, non Isiacos coniectores, non interpretes somniorum; non enim sunt ii aut scientia aut arte divini. 1 The lines that follow, '(sed)2 superstitiosi vates inpudentes harioli ... de his di vitiis sibi deducant drachmam, reddant cetera,' are normally attributed to Ennius. Some previous commentators considered that the Ennius quotation should begin earlier, specifically from 'non habeo denique nauci.' 3 In favour 1 I use here the Teubner edition of R. -

Antioch Mosaics and Their Mythological and Artistic Relations with Spanish Mosaics

JMR 5, 2012 43-57 Antioch Mosaics and their Mythological and Artistic Relations with Spanish Mosaics José Maria BLÁZQUEZ* – Javier CABRERO** The twenty-two myths represented in Antioch mosaics repeat themselves in those in Hispania. Six of the most fa- mous are selected: Judgment of Paris, Dionysus and Ariadne, Pegasus and the Nymphs, Aphrodite and Adonis, Meleager and Atalanta and Iphigenia in Aulis. Key words: Antioch myths, Hispania, Judgment of Paris, Dionysus and Ariadne, Pegasus and the Nymphs, Aphrodite and Adonis, Meleager and Atalanta, Iphigenia in Aulis During the Roman Empire, Hispania maintained good cultural and economic relationships with Syria, a Roman province that enjoyed high prosperity. Some data should be enough. An inscription from Málaga, lost today and therefore from an uncertain date, seems to mention two businessmen, collegia, from Syria, both from Asia, who might form an single college, probably dedicated to sea commerce. Through Cornelius Silvanus, a curator, they dedicated a gravestone to patron Tiberius Iulianus (D’Ors 1953: 395). They possibly exported salted fish to Syria, because Málaca had very big salting factories (Strabo III.4.2), which have been discovered. In Córdoba, possibly during the time of Emperor Elagabalus, there was a Syrian colony that offered a gravestone to several Syrian gods: Allath, Elagabab, Phren, Cypris, Athena, Nazaria, Yaris, Tyche of Antioch, Zeus, Kasios, Aphrodite Sozausa, Adonis, Iupiter Dolichenus. They were possible traders who did business in the capital of Bética (García y Bellido 1967: 96-105). Libanius the rhetorical (Declamatio, 32.28) praises the rubbles from Cádiz, which he often bought, as being good and cheap. -

Faunus and the Fauns in Latin Literature of the Republic and Early Empire

University of Adelaide Discipline of Classics Faculty of Arts Faunus and the Fauns in Latin Literature of the Republic and Early Empire Tammy DI-Giusto BA (Hons), Grad Dip Ed, Grad Cert Ed Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy October 2015 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................... 4 Thesis Declaration ................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................. 6 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 7 Context and introductory background ................................................................. 7 Significance ......................................................................................................... 8 Theoretical framework and methods ................................................................... 9 Research questions ............................................................................................. 11 Aims ................................................................................................................... 11 Literature review ................................................................................................ 11 Outline of chapters ............................................................................................ -

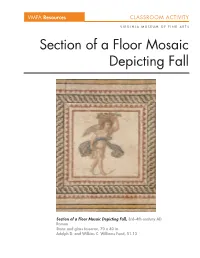

Section of a Floor Mosaic Depicting Fall

VMFA Resources CLASSROOM ACTIVITY VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS Section of a Floor Mosaic Depicting Fall Section of a Floor Mosaic Depicting Fall, 3rd–4th century AD Roman Stone and glass tesserae, 70 x 40 in. Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund, 51.13 VMFA Resources CLASSROOM ACTIVITY VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS Object Information Romans often decorated their public buildings, villas, and houses with mosaics—pictures or patterns made from small pieces of stone and glass called tesserae (tes’-er-ray). To make these mosaics, artists first created a foundation (slightly below ground level) with rocks and mortar and then poured wet cement over this mixture. Next they placed the tesserae on the cement to create a design or a picture, using different colors, materials, and sizes to achieve the effects of a painting and a more naturalistic image. Here, for instance, glass tesserae were used to add highlights and emphasize the piled-up bounty of the harvest in the basket. This mosaic panel is part of a larger continuous composition illustrating the four seasons. The seasons are personified aserotes (er-o’-tees), small boys with wings who were the mischievous companions of Eros. (Eros and his mother, Aphrodite, the Greek god and goddess of love, were known in Rome as Cupid and Venus.) Erotes were often shown in a variety of costumes; the one in this panel represents the fall season and wears a tunic with a mantle around his waist. He carries a basket of fruit on his shoulders and a pruning knife in his left hand to harvest fall fruits such as apples and grapes. -

Europe's Evolution of Atrium Houses

Europe’s evolution of atrium houses Architectural history thesis MSc Architecture, Technical University Delft MSc2 AR2A011 Architectural History Thesis S Sem van der Straaten 4652657 Europe’s evolution of atrium houses An architectural history thesis S.F.G. van der Straaten Cover image by author Acknowledgement I would like to show my appreciation to Catja Edens for guiding me, helping me keep focus on the storyline and her constructive feedback. Thank you. 14/04/21 Abstract This thesis investigates the historical evolution of the atrium house in Europe. The origin and the climatic benefits of the atrium house were found by conducting literature review. Typological variants on the atrium house are determined by testing them to a set of criteria. The traditional atrium house developed in the Roman empire from Greek and Etruscan influences. The research shows four residential variants on the atrium typology in Europe, which are: the courtyard, cortile, patio and court. These typologies with enclosed outdoor spaces have impact by offering climatic benefits and a secluded outside space which stimulates social interaction. From an architectural perspective, this research emphasizes the benefits and history of the atrium typologies. Keywords: Atrium, Benefits, Courtyard, Cortile, Court, Patio, Typologies. I Table of contents List of figures ......................................II Introduction .......................................V Chapter 1: The origin of the atrium house ...............1 1.1. Origin of the European atrium house 2 1.2. The Roman atrium house 3 1.3. Functions of the atrium 5 Chapter 2: European variants on the atrium house ........9 2.1. European atrium variants 9 2.2. Historical development of European atrium variants 11 2.2.1. -

Expulsion from the Senate of the Roman Republic, C.319–50 BC

Ex senatu eiecti sunt: Expulsion from the Senate of the Roman Republic, c.319–50 BC Lee Christopher MOORE University College London (UCL) PhD, 2013 1 Declaration I, Lee Christopher MOORE, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Thesis abstract One of the major duties performed by the censors of the Roman Republic was that of the lectio senatus, the enrolment of the Senate. As part of this process they were able to expel from that body anyone whom they deemed unequal to the honour of continued membership. Those expelled were termed ‘praeteriti’. While various aspects of this important and at-times controversial process have attracted scholarly attention, a detailed survey has never been attempted. The work is divided into two major parts. Part I comprises four chapters relating to various aspects of the lectio. Chapter 1 sees a close analysis of the term ‘praeteritus’, shedding fresh light on senatorial demographics and turnover – primarily a demonstration of the correctness of the (minority) view that as early as the third century the quaestorship conveyed automatic membership of the Senate to those who held it. It was not a Sullan innovation. In Ch.2 we calculate that during the period under investigation, c.350 members were expelled. When factoring for life expectancy, this translates to a significant mean lifetime risk of expulsion: c.10%. Also, that mean risk was front-loaded, with praetorians and consulars significantly less likely to be expelled than subpraetorian members.