Country Analysis Brief: Malaysia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mineral Facilities of Asia and the Pacific," 2007 (Open-File Report 2010-1254)

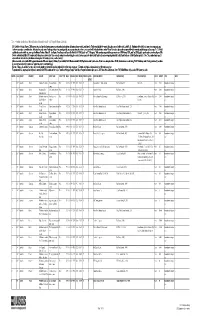

Table1.—Attribute data for the map "Mineral Facilities of Asia and the Pacific," 2007 (Open-File Report 2010-1254). [The United States Geological Survey (USGS) surveys international mineral industries to generate statistics on the global production, distribution, and resources of industrial minerals. This directory highlights the economically significant mineral facilities of Asia and the Pacific. Distribution of these facilities is shown on the accompanying map. Each record represents one commodity and one facility type for a single location. Facility types include mines, oil and gas fields, and processing plants such as refineries, smelters, and mills. Facility identification numbers (“Position”) are ordered alphabetically by country, followed by commodity, and then by capacity (descending). The “Year” field establishes the year for which the data were reported in Minerals Yearbook, Volume III – Area Reports: Mineral Industries of Asia and the Pacific. In the “DMS Latitiude” and “DMS Longitude” fields, coordinates are provided in degree-minute-second (DMS) format; “DD Latitude” and “DD Longitude” provide coordinates in decimal degrees (DD). Data were converted from DMS to DD. Coordinates reflect the most precise data available. Where necessary, coordinates are estimated using the nearest city or other administrative district.“Status” indicates the most recent operating status of the facility. Closed facilities are excluded from this report. In the “Notes” field, combined annual capacity represents the total of more facilities, plus additional -

Electricity & Gas Supply Infrastucture Malaysia

ELECTRICITY & GAS SUPPLY INFRASTRUCTURE MALAYSIA LSS2 Projects Status (Peninsular Malaysia) (Commercial Operation Date end 2019 - TBC) LSS2 Projects Status (Peninsular Malaysia) (Commercial Operation Date 2020 - TBC) PENINSULAR MALAYSIA No. Solar Power Producer (SPP) Plant Capacity (MW) Plant Location No. Solar Power Producer (SPP) Plant Capacity (MW) Plant Location MAP 2 SABAH & SARAWAK JDA A-18 1. Solution Solar 1 Sdn Bhd 4.00 Port Klang, Selangor 14. Scope Marine Sdn Bhd 5.00 Setiu, Terengganu SESB SJ- Melawa (DG 324MW, GT 20MW) Ranhill Powertron II (GT&ST) 214.8MW LSS1 Projects Status (Sabah) 2. Jentayu Solar Sdn Bhd 5.99 Pokok Sena, Kedah 15. Hong Seng Assembly Sdn Bhd 1.00 Seberang Perai Utara, Pulau Pinang No. Solar Power Producer (SPP) Plant Capacity (MW) Plant Location Karambunai Gayang 3. Solution Solar 2 Sdn Bhd 3.00 Port Klang, Selangor 16. Coral Power Sdn Bhd 9.99 Manjung, Perak Kayumadang Ranhill Powertron I (Teluk Salut) CCGT 208.64MW 1. Sabah Energy Corporation Sdn Bhd 5.00 Wilayah Persekutuan Labuan JDA B-17 4. Fairview Equity Project (Mersing) Sdn Bhd 5.00 Mersing, Johor 17. I2 Solarpark One Sdn Bhd 6.80 Alor Gajah, Melaka Unggun 2. Nusantara Suriamas Sdn Bhd 5.90 Kota Marudu, Sabah Sepanggar Bay (GT&ST) 113.8MW 5. Maju Solar (Gurun) Sdn Bhd 9.90 Kuala Muda, Kedah 18. Viva Solar Sdn Bhd 30.00 Sik, Kedah 3. Beau Energy East Sdn Bhd 6.00 Beaufort, Sabah 6. Asia Meranti Solar (Kamunting) Sdn Bhd 9.90 Kamunting, Perak 19. Cypark Estuary Solar Sdn Bhd 30.00 Empangan Terip, Negeri Sembilan UMS2 7. -

XP Travel Information for Bintulu

Shell Experienced Hire Final Assessment Travel Information – Bintulu Welcome to Shell – Travel Information CONTENTS Welcome to Shell – Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………3 Travel and Local Information…………………………………………………………………………………………..3 Your Safety……………………………………………………………………………………………………...3 Journey Management Plan……………………………………………………………………………………..3 Personal Insurance……………………………………………………………………………………………...3 Candidate Travel Booking Process ............................................................................................................. 4 Assessment Venue ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Office Address .................................................................................................................................... 5 Map…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….5 Directions to Shell Location ................................................................................................................ 5 Accommodation Hotel Information……………………………………………………………………………………………….6 Accommodation………………………………………………………………………………………………………7 Expenses……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 8 2 Welcome to Shell – Travel Information WELCOME TO SHELL – INTRODUCTION Well done progressing to the Final Assessment! We look forward to meeting you soon and finding out more about your background and great experiences. This guide should help you arrange your travel and answer any questions you have regarding travel -

Kenyataan Media JPBN Bil 218/2021 1 JAWATANKUASA

Kenyataan Media JPBN Bil 218/2021 JAWATANKUASA PENGURUSAN BENCANA NEGERI SARAWAK KENYATAAN MEDIA (06 OGOS 2021) 1. LAPORAN HARIAN A. JUMLAH KES COVID-19 JUMLAH KES BAHARU COVID-19 652 JUMLAH KUMULATIF KES COVID-19 80,174 B. PECAHAN KES COVID-19 BAHARU MENGIKUT DAERAH BILANGAN BILANGAN BIL. DAERAH BIL. DAERAH KES KES 1 Kuching 231 21 Betong 1 2 Simunjan 84 22 Meradong 1 3 Serian 65 23 Tebedu 1 4 Mukah 55 24 Kabong 0 5 Miri 34 25 Sebauh 0 6 Sibu 31 26 Dalat 0 7 Samarahan 22 27 Kapit 0 8 Bintulu 21 28 Tanjung Manis 0 9 Bau 20 29 Julau 0 10 Kanowit 18 30 Pakan 0 11 Tatau 17 31 Lawas 0 12 Sri Aman 12 32 Pusa 0 13 Selangau 12 33 Song 0 14 Lundu 11 34 Daro 0 15 Telang Usan 6 35 Belaga 0 16 Saratok 2 36 Marudi 0 17 Sarikei 2 37 Limbang 0 18 Subis 2 38 Bukit Mabong 0 19 Beluru 2 39 Lubok Antu 0 20 Asajaya 2 40 Matu 0 1 Kenyataan Media JPBN Bil 218/2021 C. RINGKASAN KES COVID-19 BAHARU TIDAK BILANGAN BIL. RINGKASAN SARINGAN BERGEJALA BERGEJALA KES Individu yang mempunyai kontak kepada kes 1 55 255 310 positif COVID-19. 2 Individu dalam kluster aktif sedia ada. 3 118 121 3 Saringan Individu bergejala di fasiliti kesihatan. 37 0 37 4 Lain-lain saringan di fasiliti kesihatan. 4 180 184 JUMLAH 99 553 652 D. KES KEMATIAN COVID-19 BAHARU: TIADA 2 Kenyataan Media JPBN Bil 218/2021 E. -

Creating Sustainable Value with Conscience Our Progress Five-Year Sustainability Key 112 to Date on the Performance Data Sustainability Front

Moving Forward Creating Sustainable Value with Conscience Our progress Five-Year Sustainability Key 112 to date on the Performance Data sustainability front. Safeguard the Environment 116 Positive Social Impact 136 Petroliam Nasional Berhad (PETRONAS) Integrated Report 2020 Five-Year Sustainability Key Performance Data Five-Year Sustainability Key Performance Data Safety Total Freshwater Withdrawal (million cubic metres per year) Number of Fatalities Employees Contractors Upstream Downstream G+NE* MISC and others** 1 3 0.85 47.02 10.25 1.91 FY2020 4 FY2020 60.03 2 0.68 46.83 10.77 2.04 FY2019 2 FY2019 60.32 6 FY2018 6 0.63 47.47 8.85 2.26 4 FY2018 59.21 FY2017 4 0.63 44.76 8.30 2.31 2 11 FY2017 56.00 FY2016 13 0.45 41.86 9.10 2.34 FY2016 53.75 Note: The non-financial data in this section does not include data from equity interest fields/projects, such as joint ventures, where we do not have operational control. Notes: Key Performance Indicators 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 * This newly established business unit (then) was fully operationalised in 2019. ** Selected non-oil and gas related operations i.e. PETRONAS Leadership Centre (PLC), KLCC Holdings. Fatal Accident Rate (FAR) 3.53 0.93 1.29 0.56 1.47 Reportable fatalities per 100 million man-hours Key Performance Indicators 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Lost Time Injury Frequency (LTIF) Discharges to Water 0.26 0.17 0.09 0.11 0.10 534 591 715 648 532 Number of cases per 1 million man-hours (metric tonnes of hydrocarbon) Total Reportable Case Frequency (TRCF) Number of Hydrocarbons Spills into -

Usp Register

SURUHANJAYA KOMUNIKASI DAN MULTIMEDIA MALAYSIA (MALAYSIAN COMMUNICATIONS AND MULTIMEDIA COMMISSION) USP REGISTER 31 DECEMBER 2018 COMMUNITY ACCESS AND SUPPORT PROGRAMME - INTERNET CENTRE No. State Parliament UST Site Name Location Kompleks Penghulu Mukim 7, Kg. Parit Hj 1 Johor Ayer Hitam Yong Peng Batu 6 Jalan Besar, Kg. Hj Ghaffar Ghaffar, 86400 Yong Peng Kompleks Kompleks Penghulu, Mukim 2 Johor Bakri Ayer Hitam Penghulu Ayer Batu 18 Setengah, 84600 Ayer Hitam Hitam Taman Rengit 9, Jalan Rengit Indah, Taman 3 Johor Batu Pahat Rengit Indah Rengit Indah, 83100 Rengit Pusat Aktiviti Kawasan Rukun 4 Johor Batu Pahat Batu Pahat Taman Nira Tetangga, Taman Nira, 83000 Batu Pahat Kompleks Penghulu, Jalan 5 Johor Gelang Patah Gelang Patah Gelang Patah Meranti, 83700 Gelang Patah Jalan Jurumudi 1, Taman Desa Desa Paya 6 Johor Gelang Patah Gelang Patah Paya Mengkuang, Mengkuang 81550 Gelang Patah Balairaya, Jalan Ilham 25, 7 Johor Kluang Taman Ilham Taman Ilham Taman Ilham, 86000 Kluang Dewan Jengking Kem Mahkota, 8 Johor Kluang Kluang Kem Mahkota 86000 Kluang Felda Bukit Pejabat JKKR Felda Bukit Aping 9 Johor Kota Tinggi Kota Tinggi Aping Barat Barat, 81900 Kota Tinggi Bilik Gerakan Persatuan Belia Felcra Sungai Felcra Sg Ara, Kawasan Sungai 10 Johor Kota Tinggi Kota Tinggi Ara Ara, KM 40 Jalan Mersing, 81900 Kota Tinggi Mini Sedili Pejabat JKKK Sedili Besar, Sedili 11 Johor Kota Tinggi Kota Tinggi Besar Besar, 81910 Kota Tinggi Felda Bukit Bekas Kilang Rossel, Felda Bukit 12 Johor Kota Tinggi Kota Tinggi Easter Easter, 81900 Kota Tinggi No. 8, Gerai Felda Pasak, 13 Johor Kota Tinggi Kota Tinggi Felda Pasak 81900 Kota Tinggi Bangunan GPW Felda Lok Heng Felda Lok 14 Johor Kota Tinggi Kota Tinggi Selatan, Sedili Kechil, Heng Selatan 81900 Kota Tinggi Bangunan Belia, Felda Bukit Felda Bukit 15 Johor Kulai Johor Bahru Permai, 81850 Layang-Layang, Permai Kulai Felda Inas Bangunan GPW, Felda Inas 16 Johor Kulai Johor Bahru Utara Utara, 81000 Kulai No. -

Kenyah-Badeng in Bakun Resettlement Malaysia

Development and displacement: Kenyah-Badeng in Bakun Resettlement Malaysia Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Bonn vorgelegt von WELYNE JEFFREY JEHOM aus Sarawak, Malaysia Bonn 2008 Gedruckt mit Genehmigung der Philosophischen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn Zusammensetzung der Prüfungskommission: Prof. Dr. Stephan Conermann (Vorsitzender) Prof. Dr. Solvay Gerke (Betreuerin und Gutachterin) Prof. Dr. Hans-Dieter Evers (Gutachter) Prof. Dr. Werner Gephart (weiteres prüfungsberechtigtes Mitglied) Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 26.06.2008 ZUSAMMENFASSUNG Im Zentrum dieser Forschungsarbeit steht die Umsiedlung der indigenen Einwohner vom Stamme der Kenyah-Badeng aus dem Dorf Long Geng in die neue Siedlung Sg. Asap in Sarawak, Malaysia. Grund für die Umsiedlung war der Bau eines Staudamms, des Bakun Hydro-electric Projektes (BHEP). Neben den Kenyah-Badeng, wurden weitere 16 Dörfer in der neuen Siedlung angesiedelt. Die Umsiedlung begann 1998 und bereits im darauffolgenden Jahr waren die neuen Langhäuser in Sg. Asap vollständig bewohnt. I. Hintergrund Umsiedlungen als Folge von Bauprojekten oder Infrastrukturmaßnahmen sind keine Seltenheit. In diesem Zusammenhang wird oft argumentiert, dass solche Projekte Arbeitsplätze für die lokale Bevölkerung schaffen und die Entwicklung fördern. Andererseits vertreibt ein solche Projekt die vor Ort lebenden Menschen von ihrer Heimstatt und ihrem traditionellen Lebensunterhalt. Im Kern der vorliegenden Studie steht der Aspekt der Zwangsumsiedlung: die Dorfbewohner von Long Geng siedelten sich ausschließlich wegen des Baus des Bakun Wasserkraftwerks in Sg. Asap an. Dies muss als Zwangsumsiedlung angesehen werden, da die indigenen Gemeinden, die früher in dem für das BHP vorgesehenen Gebiet lebten, keine andere Wahl hatten als wegzuziehen und sich anderswo wieder anzusiedeln, denn ihre Dörfer und ihr angestammtes Land wurden von der Staatsregierung für den Bau des BHP beansprucht. -

01 January 02 February 03 March 04 April 05 May 07 JULY 06 JUNE

nd rd th th MAKAN TAHUN PERDANA th th 2 -3 25 -27 Bekenu & Lambir, Miri 18 -27 KUCHING ULTRA MARATHON BORNEO CULTURAL ASEAN INTERNATIONAL “Makan Tahun” is a celebration for a Kedayan tribe in Subis District. This celebration Kuching, Sarawak FILMS FESTIVAL AND is held annually as a thanksgiving to God for a good harvest. The aim of this celebration FESTIVAL & SIBU STREET ART FESTIVAL Dataran Tun Tuanku Bujang Fasa 1 & 2 The third edition of the Road Ultra Marathon. This AWARDS (AIFFA) is to promote unity, sense of ownership and to promote the culture of the Kedayan tribe. running event consists of 30KM, 50KM, 70KM, and Subis District Office Richness of culture heritage in our motherland comprising multiracial beliefs and habits 100KM category respectively. Get ready for a meowderful Pullman Hotel, Kuching 085-719018 085-719527 is texturing the uniqueness of Sarawak. The main objective of this event is to promote adventure in Cat City capital of Sarawak. “beauty in ethnic diversity” within Borneo Island to the world. Grit Event Management The gathering of film makers and movie stars from the ASEAN region add more charm Sibu Municipal Council CALENDAR OF TOURISM EVENTS 016-878 2809 084-333411 084-320240 to the rustic city. Sanctioned by ASEAN secretariat as one of the ASEAN joint activities, st rd the festival is held in every two years. 1 -3 th st th th th th World Communication Network Resources (M) Sdn Bhd IRAU 19 -21 2019 7 -9 5 -7 082-414661 082-240661 ALTA MODA SARAWAK (AMS) BALEH-KAPIT RAFT SAFARI ACO LUN BORNEO JAZZ Kapit Town FESTIVAL For further information, contact: Old DUN Building, Kuching BAWANG MINISTRY OF TOURISM, ARTS, CULTURE, An annual rafting competition held along the Rejang River. -

PETRONAS Capital Limited Petroliam Nasional Berhad

OFFERING CIRCULAR (AND LUXEMBOURG LISTING PROSPECTUS) PETRONAS Capital Limited (incorporated in Labuan, Malaysia with limited liability) US$3,000,000,000 5.25% GUARANTEED NOTES DUE 2019 unconditionally and irrevocably guaranteed by Petroliam Nasional Berhad (incorporated in Malaysia with limited liability) PRICE 99.447% PLUS ACCRUED INTEREST, IF ANY, FROM AUGUST 12, 2009 The 5.25% Guaranteed Notes due 2019 in the aggregate principal amount of US$3,000,000,000 (the “Notes”) will be issued by PETRONAS Capital Limited (“PETRONAS Capital Limited” or the “Issuer”) and will be unconditionally and irrevocably guaranteed by Petroliam Nasional Berhad (“PETRONAS”). PETRONAS Capital Limited is a wholly-owned special purpose finance subsidiary of PETRONAS, which has been established for the purpose of issuing debt securities and other obligations from time to time to finance the operations of PETRONAS. PETRONAS Capital Limited will provide the proceeds of the offering to PETRONAS or its subsidiaries and associated companies. The Notes will be unsecured obligations of PETRONAS Capital Limited and will rank pari passu among themselves and with all of its other unsecured and unsubordinated obligations. PETRONAS’ guarantee (the “Guarantee”) will be an unsecured obligation of PETRONAS, will rank pari passu with its other unsecured and unsubordinated obligations and will be effectively subordinated to the secured obligations of PETRONAS and the obligations of its subsidiaries. Unless previously repurchased, cancelled or redeemed, the Notes will mature on August 12, 2019. The Notes will be redeemed at 100% of their principal amount plus accrued and unpaid interest, if any, on the maturity date. The Notes will bear interest at a rate of 5.25% per year, payable semi-annually in arrears on February 12 and August 12 of each year. -

2016 Annual Report

Power to Grow SUSTAINABLE ENERGY FOR SARAWAK AND BEYOND ANNUAL REPORT 2016 SUSTAINABLE ENERGY FOR SARAWAK AND BEYOND “Sustainable energy for Sarawak and beyond” captures our ambition to provide clean and reliable power for the growth and prosperity of the region. This year, we officially opened the Murum Hydroelectric Plant, enabling us to deliver an additional 944MW of energy to Sarawak; began to export power to West Kalimantan in Indonesia; signed a letter of intent with the Northern Province of Kalimantan and continued our plans to work with Brunei and Sabah to advance the Borneo Grid. As we develop our indigenous natural resources in pursuit of economic and social progress, renewable, reliable and affordable energy will play an increasingly vital role in accelerating sustainable development for Sarawak and the region. Murum HEP is located on the Murum River in the upper Rajang River basin, 200km from Bintulu. It is designed to produce 711MW (constant) and 944MW (peak) from a 2,750sq km catchment area feeding a 270sq km reservoir. Construction began in 2008 and by mid-2015 the station was fully operational, delivering its specified power into the State Grid. INSIDE THIS REPORT About this Report 03 Chairman’s Message 20 2016 Key Highlights 06 Group CEO’s Message 24 About Sarawak Energy 08 Management Discussion & Analysis 28 Corporate Information 09 Developing Our People, Leadership Vision, Mission & Living Our Values 11 and Teamwork 31 OVERVIEW Five-Year Group Financial Highlights 12 Health, Safety and Environment 35 OF SARAWAK ENERGY -

P17004 Plant 3 EIA Chapter 6

Environmental Impact Assessment for Proposed Expansion of Project No: P17004 Aluminium Smelting Plant on Lot 36, Samalaju Industrial Park, Revision: 0 Bintulu, Sarawak for Press Metal Bintulu Sdn. Bhd. Date: June 2019 CHAPTER 6 EXISTING ENVIRONMENT 6.1 INTRODUCTION This section presents the existing environmental characteristics within 5 km radius from the Project site boundaries (Zone of Study). Information collected and sourced covered three (3) major components, namely physical, chemical, biological and human activities within the Project’s vicinity to provide an overview of existing environmental conditions of the surrounding the project site at the time of Study. The Zone of Study extends 5 km from the boundary of the study area that covers the overall Press Metal premise including the Line 1 and Line 2 areas. In the event, the assessment impacts are found extending beyond the Zone of Study, the Zone of Study may be expanded where necessary. 6.2 PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT Premise Physical Setting Lot 36 has total area of 480 acres (195 hectares) and is divided into three (3) blocks as shown in Figure 1-2 and Figure 5-1. Plant 1 is located in Block 1 which is located towards the northern section of Lot 36 while Plant 2 is sited in Block 2 Phase 1 which is located adjacent to Block 1 and in the middle section of Lot 36. Remaining of Block 2 is marked for Phase 2, i.e. for the Project, and for Phase 3, i.e. for future development, whereby both are located towards the southern section. In between Plant 1 and Plant 2, a 70 m buffer is provided and currently houses the supporting components for the operations, such as storage silos, weighing station and concrete batching plant. -

(06 JULAI 2021) 1. LAPORAN HARIAN A. Status Kes COVID-19 Di

Kenyataan Media JPBN Bil 187/2021 JAWATANKUASA PENGURUSAN BENCANA NEGERI SARAWAK KENYATAAN MEDIA (06 JULAI 2021) 1. LAPORAN HARIAN A. Status Kes COVID-19 Di Dalam Wad Hospital Dan Masih Di PKRC. Hari ini terdapat 371 kes baharu yang telah pulih dan dibenarkan discaj pada hari ini iaitu: • 108 kes dari Hospital Umum Sarawak dan PKRC di bawah Hospital Umum Sarawak; • 70 kes dari Hospital Bintulu dan PKRC di bawah Hospital Bintulu; • 42 kes dari Hospital Sibu dan PKRC di di bawah Hospital Sibu; • 37 kes dari Hospital Miri dan PKRC di bawah Hospital Miri; • 36 kes dari Hospital Sri Aman dan PKRC Sri Aman; • 26 kes dari PKRC Serian; • 19 kes dari PKRC Mukah; • 17 kes dari Hospital Sarikei dan PKRC di bawah Hospital Sarikei; • 12 kes dari Hospital Kapit dan PKRC di bawah Hospital Kapit; • 2 kes dari PKRC Betong; • 1 kes dari PKRC Lawas; dan • 1 kes dari Hospital Limbang. 1 Kenyataan Media JPBN Bil 187/2021 Ini menjadikan jumlah keseluruhan kes positif COVID-19 yang telah pulih atau dibenarkan discaj setakat hari ini adalah seramai 56,745 orang atau 84.35% dari jumlah keseluruhan kes COVID-19 di Sarawak. Jumlah kes aktiF yang masih mendapat rawatan dan diasingkan di PKRC dan wad hospital mengikut hospital rujukan adalah seramai 9,950 orang. B. Kes Baharu COVID-19. Hari ini terdapat 286 kes baharu COVID-19 dikesan. Sejumlah 199 atau 69.58 peratus daripada jumlah kes ini telah dikesan di lima (5) buah daerah iaitu di Daerah Kuching, Subis, Miri, Sibu dan Bintulu. Daerah-daerah yang merekodkan kes pada hari ini ialah daerah Kuching (85), Subis (50), Miri (32), Sibu (21), Bintulu (11), Saratok (11), Serian (11), Song (8), Asajaya (8), Sri Aman (7), Kapit (7), Bau (5), Bukit Mabong (5), Telang Usan (5), Tatau (4), Samarahan (4), Kanowit (3), Sarikei (2), Tanjung Manis (2), Simunjan (1), Selangau (1), Meradong (1), Beluru (1) dan Lundu (1).