Kenyah-Badeng in Bakun Resettlement Malaysia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Further Miscellaneous Species of Cyrtandra in Borneo

E D I N B U R G H J O U R N A L O F B O T A N Y 63 (2&3): 209–229 (2006) 209 doi:10.1017/S0960428606000564 E Trustees of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (2006) Issued 30 November 2006 OLD WORLD GESNERIACEAE XII: FURTHER MISCELLANEOUS SPECIES OF CYRTANDRA IN BORNEO O. M. HILLIARD &B.L.BURTT Nineteen miscellaneous species of Bornean Cyrtandra are dealt with. Cyrtandra atrichoides, C. congestiflora, C. crockerella, C. dulitiana, C. kanae, C. libauensis, C. plicata, C. vaginata and C. disparoides subsp. inconspicua are newly described. Descriptions and discussion are provided for C. erythrotricha and C. poulsenii, originally published with diagnoses only. Cyrtandra axillaris, C. longicarpa and C. microcarpa are also described, while C. borneensis, C. dajakorum, C. glomeruliflora, C. latens and C. prolata are reduced to synonymy. Keywords. Borneo, Cyrtandra, Gesneriaceae, new species. I NTRODUCTION A good many species of Cyrtandra in Borneo still remain undescribed; some available specimens are known to us only in the sterile state or are otherwise inadequate to typify a name. In this paper eight species and one subspecies are newly described. Burtt (1996) published new species with diagnoses only: C. erythrotricha B.L.Burtt and C. poulsenii B.L.Burtt are now fully described while C. glomeruliflora B.L.Burtt is reduced to synonymy under C. poulsenii. Full descriptions of C. axillaris C.B.Clarke and C. microcarpa C.B.Clarke are also given for the first time with the reduction of C. latens C.B.Clarke and C. dajakorum Kraenzl. -

Polygalaceae) from Borneo

Gardens' Bulletin Singapore 57 (2005) 47–61 47 New Taxa and Taxonomic Status in Xanthophyllum Roxb. (Polygalaceae) from Borneo W.J.J.O. DE WILDE AND BRIGITTA E.E. DUYFJES National Herbarium of the Netherlands, Leiden Branch P.O. Box 9514, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands Abstract Thirteen new taxa or taxa with a new status in Xanthophyllum (Polygalaceae) from Borneo are described. The ten new species described in this paper are: X. bicolor W.J. de Wilde & Duyfjes, X. brachystachyum W.J. de Wilde & Duyfjes, X. crassum W.J. de Wilde & Duyfjes, X. inflatum W.J. de Wilde & Duyfjes, X. ionanthum W.J. de Wilde & Duyfjes, X. longum W.J. de Wilde & Duyfjes, X. nitidum W.J. de Wilde & Duyfjes, X. pachycarpon W.J. de Wilde & Duyfjes, X. rectum W.J. de Wilde & Duyfjes and X. rheophilum W.J. de Wilde & Duyfjes, and the new variety is X. griffithii A.W. Benn var. papillosum W.J. de Wilde & Duyfjes. New taxonomic status has been accorded to X. adenotus Miq. var. arsatii (C.E.C. Fisch.) W.J. de Wilde & Duyfjes and X. lineare (Meijden) W.J. de Wilde & Duyfjes. Introduction During the study of Xanthophyllum carried out in the BO, KEP, L, SAN, SAR and SING herbaria for the account of Polygalaceae in the Tree Flora of Sabah and Sarawak, several new taxa were defined. Their taxonomic position within the more than 50 species of Xanthophyllum recognised in Sabah and Sarawak will be clarified in the treatment of the family in the forthcoming volume of the Tree Flora of Sabah and Sarawak series. -

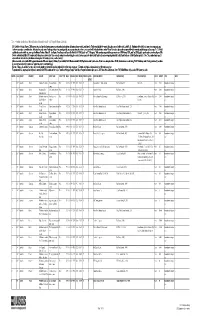

Mineral Facilities of Asia and the Pacific," 2007 (Open-File Report 2010-1254)

Table1.—Attribute data for the map "Mineral Facilities of Asia and the Pacific," 2007 (Open-File Report 2010-1254). [The United States Geological Survey (USGS) surveys international mineral industries to generate statistics on the global production, distribution, and resources of industrial minerals. This directory highlights the economically significant mineral facilities of Asia and the Pacific. Distribution of these facilities is shown on the accompanying map. Each record represents one commodity and one facility type for a single location. Facility types include mines, oil and gas fields, and processing plants such as refineries, smelters, and mills. Facility identification numbers (“Position”) are ordered alphabetically by country, followed by commodity, and then by capacity (descending). The “Year” field establishes the year for which the data were reported in Minerals Yearbook, Volume III – Area Reports: Mineral Industries of Asia and the Pacific. In the “DMS Latitiude” and “DMS Longitude” fields, coordinates are provided in degree-minute-second (DMS) format; “DD Latitude” and “DD Longitude” provide coordinates in decimal degrees (DD). Data were converted from DMS to DD. Coordinates reflect the most precise data available. Where necessary, coordinates are estimated using the nearest city or other administrative district.“Status” indicates the most recent operating status of the facility. Closed facilities are excluded from this report. In the “Notes” field, combined annual capacity represents the total of more facilities, plus additional -

TITLE Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program: Malaysia 1995

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 405 265 SO 026 916 TITLE Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program: Malaysia 1995. Participants' Reports. INSTITUTION Center for International Education (ED), Washington, DC.; Malaysian-American Commission on Educational Exchange, Kuala Lumpur. PUB DATE 95 NOTE 321p.; Some images will not reproduce clearly. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) Reports Descriptive (141) Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; *Asian History; *Asian Studies; Cultural Background; Culture; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; Foreign Culture; *Global Education; Human Geography; Instructional Materials; *Non Western Civilization; Social Studies; *World Geography; *World History IDENTIFIERS Fulbright Hays Seminars Abroad Program; *Malaysia ABSTRACT These reports and lesson plans were developed by teachers and coordinators who traveled to Malaysia during the summer of 1995 as part of the U.S. Department of Education's Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program. Sections of the report include:(1) "Gender and Economics: Malaysia" (Mary C. Furlong);(2) "Malaysia: An Integrated, Interdisciplinary Social Studies Unit for Middle School/High School Students" (Nancy K. Hof);(3) "Malaysian Adventure: The Cultural Diversity of Malaysia" (Genevieve M. Homiller);(4) "Celebrating Cultural Diversity: The Traditional Malay Marriage Ritual" (Dorene H. James);(5) "An Introduction of Malaysia: A Mini-unit for Sixth Graders" (John F. Kennedy); (6) "Malaysia: An Interdisciplinary Unit in English Literature and Social Studies" (Carol M. Krause);(7) "Malaysia and the Challenge of Development by the Year 2020" (Neale McGoldrick);(8) "The Iban: From Sea Pirates to Dwellers of the Rain Forest" (Margaret E. Oriol);(9) "Vision 2020" (Louis R. Price);(10) "Sarawak for Sale: A Simulation of Environmental Decision Making in Malaysia" (Kathleen L. -

The Provider-Based Evaluation (Probe) 2014 Preliminary Report

The Provider-Based Evaluation (ProBE) 2014 Preliminary Report I. Background of ProBE 2014 The Provider-Based Evaluation (ProBE), continuation of the formerly known Malaysia Government Portals and Websites Assessment (MGPWA), has been concluded for the assessment year of 2014. As mandated by the Government of Malaysia via the Flagship Coordination Committee (FCC) Meeting chaired by the Secretary General of Malaysia, MDeC hereby announces the result of ProBE 2014. Effective Date and Implementation The assessment year for ProBE 2014 has commenced on the 1 st of July 2014 following the announcement of the criteria and its methodology to all agencies. A total of 1086 Government websites from twenty four Ministries and thirteen states were identified for assessment. Methodology In line with the continuous and heightened effort from the Government to enhance delivery of services to the citizens, significant advancements were introduced to the criteria and methodology of assessment for ProBE 2014 exercise. The year 2014 spearheaded the introduction and implementation of self-assessment methodology where all agencies were required to assess their own websites based on the prescribed ProBE criteria. The key features of the methodology are as follows: ● Agencies are required to conduct assessment of their respective websites throughout the year; ● Parents agencies played a vital role in monitoring as well as approving their agencies to be able to conduct the self-assessment; ● During the self-assessment process, each agency is required to record -

The Response of the Indigenous Peoples of Sarawak

Third WorldQuarterly, Vol21, No 6, pp 977 – 988, 2000 Globalizationand democratization: the responseo ftheindigenous peoples o f Sarawak SABIHAHOSMAN ABSTRACT Globalizationis amulti-layered anddialectical process involving two consequenttendencies— homogenizing and particularizing— at the same time. Thequestion of howand in whatways these contendingforces operatein Sarawakand in Malaysiaas awholeis therefore crucial in aneffort to capture this dynamic.This article examinesthe impactof globalizationon the democra- tization process andother domestic political activities of the indigenouspeoples (IPs)of Sarawak.It shows howthe democratizationprocess canbe anempower- ingone, thus enablingthe actors to managethe effects ofglobalization in their lives. Thecon ict betweenthe IPsandthe state againstthe depletionof the tropical rainforest is manifested in the form of blockadesand unlawful occu- pationof state landby the former as aform of resistance andprotest. Insome situations the federal andstate governmentshave treated this actionas aserious globalissue betweenthe international NGOsandthe Malaysian/Sarawakgovern- ment.In this case globalizationhas affected boththe nation-state andthe IPs in different ways.Globalization has triggered agreater awareness of self-empow- erment anddemocratization among the IPs. These are importantforces in capturingsome aspects of globalizationat the local level. Globalization is amulti-layered anddialectical process involvingboth homoge- nization andparticularization, ie the rise oflocalism in politics, economics, -

Electricity & Gas Supply Infrastucture Malaysia

ELECTRICITY & GAS SUPPLY INFRASTRUCTURE MALAYSIA LSS2 Projects Status (Peninsular Malaysia) (Commercial Operation Date end 2019 - TBC) LSS2 Projects Status (Peninsular Malaysia) (Commercial Operation Date 2020 - TBC) PENINSULAR MALAYSIA No. Solar Power Producer (SPP) Plant Capacity (MW) Plant Location No. Solar Power Producer (SPP) Plant Capacity (MW) Plant Location MAP 2 SABAH & SARAWAK JDA A-18 1. Solution Solar 1 Sdn Bhd 4.00 Port Klang, Selangor 14. Scope Marine Sdn Bhd 5.00 Setiu, Terengganu SESB SJ- Melawa (DG 324MW, GT 20MW) Ranhill Powertron II (GT&ST) 214.8MW LSS1 Projects Status (Sabah) 2. Jentayu Solar Sdn Bhd 5.99 Pokok Sena, Kedah 15. Hong Seng Assembly Sdn Bhd 1.00 Seberang Perai Utara, Pulau Pinang No. Solar Power Producer (SPP) Plant Capacity (MW) Plant Location Karambunai Gayang 3. Solution Solar 2 Sdn Bhd 3.00 Port Klang, Selangor 16. Coral Power Sdn Bhd 9.99 Manjung, Perak Kayumadang Ranhill Powertron I (Teluk Salut) CCGT 208.64MW 1. Sabah Energy Corporation Sdn Bhd 5.00 Wilayah Persekutuan Labuan JDA B-17 4. Fairview Equity Project (Mersing) Sdn Bhd 5.00 Mersing, Johor 17. I2 Solarpark One Sdn Bhd 6.80 Alor Gajah, Melaka Unggun 2. Nusantara Suriamas Sdn Bhd 5.90 Kota Marudu, Sabah Sepanggar Bay (GT&ST) 113.8MW 5. Maju Solar (Gurun) Sdn Bhd 9.90 Kuala Muda, Kedah 18. Viva Solar Sdn Bhd 30.00 Sik, Kedah 3. Beau Energy East Sdn Bhd 6.00 Beaufort, Sabah 6. Asia Meranti Solar (Kamunting) Sdn Bhd 9.90 Kamunting, Perak 19. Cypark Estuary Solar Sdn Bhd 30.00 Empangan Terip, Negeri Sembilan UMS2 7. -

Borneo Research Bulletin, Deparunenr

RESEAR BULLETIN --1. 7, NO. 2 September -1975 Notes From the Editor: Appreciation to Donald E. Brown; Contributions for the support of the BRC; Suggestions for future issues; List of Fellows ................... 4 4 Research Notes Distribution of Penan and Punan in the Belaga District ................Jay1 Langub 45 Notes on the Kelabit ........... Mady Villard 49 The Distribution of Secondary Treatment of the Dead in Central North mrneo ...Peter Metcalf 54 Socio-Ecological Sketch of Two Sarawak Longhouses ............. Dietrich Kuhne i 60 Brief Communications The Rhinoceros and Mammal Extinction in General ...............Tom Harrisson 71 News and Announcements ! Mervyn Aubrey Jaspan, 1926-1975. An Obituary ............... Tom Harrisson Doctoral Dissertations on Asia .... Frank J. Shulman Borneo News .................... Book Reviews, Abstracts and Bibliography Tom Harrisson: Prehistoric Wood from Brunei, Borneo. (Barbara Harrisson) ............ Michael and Patricia Fogden: Animals and Their Colours. (Tom Harrisson) ...... Elliott McClure: Migration and Survival of the Birds of Asia. (Tom Harrisson) .... The Borneo Research Bullt e yearly (A and September) by the 601 Please ad all inquiries and contribut:ons ror pwllcacioln to Vinson bUC- 'live, Editor, Borneo Research Bulletin, Deparunenr... or Anthropology. College of William ant liamsburg, 'Virginia 231 85. U.S.A. Single isaiues are ave JSS?.50. 14- -45- 1 kak Reviews, Abstracts and Biblioqraphy (cont.) RESEARCH NOTES Sevinc Carlson: Malaysia: Search for National Unity and Economic Growth .............................. 7 9 DISTRIBUTION OF PENAN AND PUNAN IN THE: BELAGA DISTRICT Robert Reece: The Cession of Sarawak to the British Crown in 1946 . ' Jay1 Langub Joan Seele,r: Kenyah A Description and ' I S.... ...........80 hy ... ........... 80 After reading the reports on the Punan in Kalimantan by Victor xing and H.L. -

Penyata Rasmi Official Report

Jilid III 1I fi fl fi F% Hari Selasa BiL 25 24hb Julai, 1973 PENYATA RASMI OFFICIAL REPORT DEWAN RAKYAT HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES PARLIMEN KETIGA Third Parliament PENGGAL PARLIMEN KETIGA Third Session KANDUNGANNYA JAWAPAN-JAWAPAN MULUT BAG! PERTANYAAN-PERTANYAAN [ Ruangan 28471 RANG UNDANG-UNDANG DIBAWA KE DALA.M MESYUARAT [Ruangan 28881 USUL-USUL: Waktu Mesyuarat dan Urusan Yang Dibebaskan daripada Peraturan Mesyuarat dan Penangguhan [Ruangan 28801 Ordinan Setem, 1949- Pindaan kepada Jadual Pertama seksyen 4 (4) [Ruangan 2917] Parliament (Members' Remuneration ) Act, 1960 (Amendment to Schedule ) [Ruangan 2918] JAWATANKUASA PILIHAN-USUL DITARIK BALIK [Ruangan 29251 UCAPAN PENANGGUHAN- Pelan Induk bagi Bandaraya Kuala Lwnpur [Ruangan 2926] RANG UNDANG-UNDANG: Rang Undang-undang Kerajaan Tempatan (Peruntukan-peruntukan Sementara) [Ruangan 2881] JAWAPAN-JAWAPAN BERTULIS [Ruangan 2933] MALAYSIA DEWAN RAKYAT YANG KETIGA Penyata Rasmi PENGGAL YANG KETIGA Hari Selasa, 24hb Julai, 1973 11lesyuarat dimulakan pada pukul 2.30 petang YANG HADIR : Yang Berhormat Tuan Yang di-Pertua, TAN SRI DATUK CIK MOHAMED YUSUF BIN SHEIKH ABDUL RAHMAN, P.M.N., S. P.M.P., J .P., Datuk Bendahara Perak. „ Menteri Perhubungan, TAN SRI HAJI SARDON BIN HAJI JUBIR, P.M.N., S. P.M.K., S . P.M.J. (Pontian Utara). „ Menteri Tak Berpotfolio, TUAN MOHAMED KHIR JOHARI (Kedah Tengah). Menteri Buruh dan Tenaga Rakyat, TAN SRI V. MANICKAVASAGAM, P.M.N., S.P.M.S., J.M.N., P.J.K. (Kelang). Menteri Pembangunan Negara dan Luar Bandar, TUAN ABDUL GHAFAR BIN BABA (Melaka Utara). „ Menteri Kerja Raya dan Tenaga, DATUK HAJI ABDUL GHANI GILONG, P.D.K., J.P . (Kinabalu). Menteri Kemajuan Tanah dan Menteri Tugas-tugas Khas, DATUK HAJI MOHAMED ASRI BIN HAJI MUDA, S.P.M.K. -

XP Travel Information for Bintulu

Shell Experienced Hire Final Assessment Travel Information – Bintulu Welcome to Shell – Travel Information CONTENTS Welcome to Shell – Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………3 Travel and Local Information…………………………………………………………………………………………..3 Your Safety……………………………………………………………………………………………………...3 Journey Management Plan……………………………………………………………………………………..3 Personal Insurance……………………………………………………………………………………………...3 Candidate Travel Booking Process ............................................................................................................. 4 Assessment Venue ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Office Address .................................................................................................................................... 5 Map…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….5 Directions to Shell Location ................................................................................................................ 5 Accommodation Hotel Information……………………………………………………………………………………………….6 Accommodation………………………………………………………………………………………………………7 Expenses……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 8 2 Welcome to Shell – Travel Information WELCOME TO SHELL – INTRODUCTION Well done progressing to the Final Assessment! We look forward to meeting you soon and finding out more about your background and great experiences. This guide should help you arrange your travel and answer any questions you have regarding travel -

Kenyataan Media JPBN Bil 218/2021 1 JAWATANKUASA

Kenyataan Media JPBN Bil 218/2021 JAWATANKUASA PENGURUSAN BENCANA NEGERI SARAWAK KENYATAAN MEDIA (06 OGOS 2021) 1. LAPORAN HARIAN A. JUMLAH KES COVID-19 JUMLAH KES BAHARU COVID-19 652 JUMLAH KUMULATIF KES COVID-19 80,174 B. PECAHAN KES COVID-19 BAHARU MENGIKUT DAERAH BILANGAN BILANGAN BIL. DAERAH BIL. DAERAH KES KES 1 Kuching 231 21 Betong 1 2 Simunjan 84 22 Meradong 1 3 Serian 65 23 Tebedu 1 4 Mukah 55 24 Kabong 0 5 Miri 34 25 Sebauh 0 6 Sibu 31 26 Dalat 0 7 Samarahan 22 27 Kapit 0 8 Bintulu 21 28 Tanjung Manis 0 9 Bau 20 29 Julau 0 10 Kanowit 18 30 Pakan 0 11 Tatau 17 31 Lawas 0 12 Sri Aman 12 32 Pusa 0 13 Selangau 12 33 Song 0 14 Lundu 11 34 Daro 0 15 Telang Usan 6 35 Belaga 0 16 Saratok 2 36 Marudi 0 17 Sarikei 2 37 Limbang 0 18 Subis 2 38 Bukit Mabong 0 19 Beluru 2 39 Lubok Antu 0 20 Asajaya 2 40 Matu 0 1 Kenyataan Media JPBN Bil 218/2021 C. RINGKASAN KES COVID-19 BAHARU TIDAK BILANGAN BIL. RINGKASAN SARINGAN BERGEJALA BERGEJALA KES Individu yang mempunyai kontak kepada kes 1 55 255 310 positif COVID-19. 2 Individu dalam kluster aktif sedia ada. 3 118 121 3 Saringan Individu bergejala di fasiliti kesihatan. 37 0 37 4 Lain-lain saringan di fasiliti kesihatan. 4 180 184 JUMLAH 99 553 652 D. KES KEMATIAN COVID-19 BAHARU: TIADA 2 Kenyataan Media JPBN Bil 218/2021 E. -

Creating Sustainable Value with Conscience Our Progress Five-Year Sustainability Key 112 to Date on the Performance Data Sustainability Front

Moving Forward Creating Sustainable Value with Conscience Our progress Five-Year Sustainability Key 112 to date on the Performance Data sustainability front. Safeguard the Environment 116 Positive Social Impact 136 Petroliam Nasional Berhad (PETRONAS) Integrated Report 2020 Five-Year Sustainability Key Performance Data Five-Year Sustainability Key Performance Data Safety Total Freshwater Withdrawal (million cubic metres per year) Number of Fatalities Employees Contractors Upstream Downstream G+NE* MISC and others** 1 3 0.85 47.02 10.25 1.91 FY2020 4 FY2020 60.03 2 0.68 46.83 10.77 2.04 FY2019 2 FY2019 60.32 6 FY2018 6 0.63 47.47 8.85 2.26 4 FY2018 59.21 FY2017 4 0.63 44.76 8.30 2.31 2 11 FY2017 56.00 FY2016 13 0.45 41.86 9.10 2.34 FY2016 53.75 Note: The non-financial data in this section does not include data from equity interest fields/projects, such as joint ventures, where we do not have operational control. Notes: Key Performance Indicators 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 * This newly established business unit (then) was fully operationalised in 2019. ** Selected non-oil and gas related operations i.e. PETRONAS Leadership Centre (PLC), KLCC Holdings. Fatal Accident Rate (FAR) 3.53 0.93 1.29 0.56 1.47 Reportable fatalities per 100 million man-hours Key Performance Indicators 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Lost Time Injury Frequency (LTIF) Discharges to Water 0.26 0.17 0.09 0.11 0.10 534 591 715 648 532 Number of cases per 1 million man-hours (metric tonnes of hydrocarbon) Total Reportable Case Frequency (TRCF) Number of Hydrocarbons Spills into