Environmental Impact Assessment Process in Malaysia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Further Miscellaneous Species of Cyrtandra in Borneo

E D I N B U R G H J O U R N A L O F B O T A N Y 63 (2&3): 209–229 (2006) 209 doi:10.1017/S0960428606000564 E Trustees of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (2006) Issued 30 November 2006 OLD WORLD GESNERIACEAE XII: FURTHER MISCELLANEOUS SPECIES OF CYRTANDRA IN BORNEO O. M. HILLIARD &B.L.BURTT Nineteen miscellaneous species of Bornean Cyrtandra are dealt with. Cyrtandra atrichoides, C. congestiflora, C. crockerella, C. dulitiana, C. kanae, C. libauensis, C. plicata, C. vaginata and C. disparoides subsp. inconspicua are newly described. Descriptions and discussion are provided for C. erythrotricha and C. poulsenii, originally published with diagnoses only. Cyrtandra axillaris, C. longicarpa and C. microcarpa are also described, while C. borneensis, C. dajakorum, C. glomeruliflora, C. latens and C. prolata are reduced to synonymy. Keywords. Borneo, Cyrtandra, Gesneriaceae, new species. I NTRODUCTION A good many species of Cyrtandra in Borneo still remain undescribed; some available specimens are known to us only in the sterile state or are otherwise inadequate to typify a name. In this paper eight species and one subspecies are newly described. Burtt (1996) published new species with diagnoses only: C. erythrotricha B.L.Burtt and C. poulsenii B.L.Burtt are now fully described while C. glomeruliflora B.L.Burtt is reduced to synonymy under C. poulsenii. Full descriptions of C. axillaris C.B.Clarke and C. microcarpa C.B.Clarke are also given for the first time with the reduction of C. latens C.B.Clarke and C. dajakorum Kraenzl. -

Polygalaceae) from Borneo

Gardens' Bulletin Singapore 57 (2005) 47–61 47 New Taxa and Taxonomic Status in Xanthophyllum Roxb. (Polygalaceae) from Borneo W.J.J.O. DE WILDE AND BRIGITTA E.E. DUYFJES National Herbarium of the Netherlands, Leiden Branch P.O. Box 9514, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands Abstract Thirteen new taxa or taxa with a new status in Xanthophyllum (Polygalaceae) from Borneo are described. The ten new species described in this paper are: X. bicolor W.J. de Wilde & Duyfjes, X. brachystachyum W.J. de Wilde & Duyfjes, X. crassum W.J. de Wilde & Duyfjes, X. inflatum W.J. de Wilde & Duyfjes, X. ionanthum W.J. de Wilde & Duyfjes, X. longum W.J. de Wilde & Duyfjes, X. nitidum W.J. de Wilde & Duyfjes, X. pachycarpon W.J. de Wilde & Duyfjes, X. rectum W.J. de Wilde & Duyfjes and X. rheophilum W.J. de Wilde & Duyfjes, and the new variety is X. griffithii A.W. Benn var. papillosum W.J. de Wilde & Duyfjes. New taxonomic status has been accorded to X. adenotus Miq. var. arsatii (C.E.C. Fisch.) W.J. de Wilde & Duyfjes and X. lineare (Meijden) W.J. de Wilde & Duyfjes. Introduction During the study of Xanthophyllum carried out in the BO, KEP, L, SAN, SAR and SING herbaria for the account of Polygalaceae in the Tree Flora of Sabah and Sarawak, several new taxa were defined. Their taxonomic position within the more than 50 species of Xanthophyllum recognised in Sabah and Sarawak will be clarified in the treatment of the family in the forthcoming volume of the Tree Flora of Sabah and Sarawak series. -

TITLE Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program: Malaysia 1995

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 405 265 SO 026 916 TITLE Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program: Malaysia 1995. Participants' Reports. INSTITUTION Center for International Education (ED), Washington, DC.; Malaysian-American Commission on Educational Exchange, Kuala Lumpur. PUB DATE 95 NOTE 321p.; Some images will not reproduce clearly. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) Reports Descriptive (141) Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; *Asian History; *Asian Studies; Cultural Background; Culture; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; Foreign Culture; *Global Education; Human Geography; Instructional Materials; *Non Western Civilization; Social Studies; *World Geography; *World History IDENTIFIERS Fulbright Hays Seminars Abroad Program; *Malaysia ABSTRACT These reports and lesson plans were developed by teachers and coordinators who traveled to Malaysia during the summer of 1995 as part of the U.S. Department of Education's Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program. Sections of the report include:(1) "Gender and Economics: Malaysia" (Mary C. Furlong);(2) "Malaysia: An Integrated, Interdisciplinary Social Studies Unit for Middle School/High School Students" (Nancy K. Hof);(3) "Malaysian Adventure: The Cultural Diversity of Malaysia" (Genevieve M. Homiller);(4) "Celebrating Cultural Diversity: The Traditional Malay Marriage Ritual" (Dorene H. James);(5) "An Introduction of Malaysia: A Mini-unit for Sixth Graders" (John F. Kennedy); (6) "Malaysia: An Interdisciplinary Unit in English Literature and Social Studies" (Carol M. Krause);(7) "Malaysia and the Challenge of Development by the Year 2020" (Neale McGoldrick);(8) "The Iban: From Sea Pirates to Dwellers of the Rain Forest" (Margaret E. Oriol);(9) "Vision 2020" (Louis R. Price);(10) "Sarawak for Sale: A Simulation of Environmental Decision Making in Malaysia" (Kathleen L. -

The Provider-Based Evaluation (Probe) 2014 Preliminary Report

The Provider-Based Evaluation (ProBE) 2014 Preliminary Report I. Background of ProBE 2014 The Provider-Based Evaluation (ProBE), continuation of the formerly known Malaysia Government Portals and Websites Assessment (MGPWA), has been concluded for the assessment year of 2014. As mandated by the Government of Malaysia via the Flagship Coordination Committee (FCC) Meeting chaired by the Secretary General of Malaysia, MDeC hereby announces the result of ProBE 2014. Effective Date and Implementation The assessment year for ProBE 2014 has commenced on the 1 st of July 2014 following the announcement of the criteria and its methodology to all agencies. A total of 1086 Government websites from twenty four Ministries and thirteen states were identified for assessment. Methodology In line with the continuous and heightened effort from the Government to enhance delivery of services to the citizens, significant advancements were introduced to the criteria and methodology of assessment for ProBE 2014 exercise. The year 2014 spearheaded the introduction and implementation of self-assessment methodology where all agencies were required to assess their own websites based on the prescribed ProBE criteria. The key features of the methodology are as follows: ● Agencies are required to conduct assessment of their respective websites throughout the year; ● Parents agencies played a vital role in monitoring as well as approving their agencies to be able to conduct the self-assessment; ● During the self-assessment process, each agency is required to record -

The Response of the Indigenous Peoples of Sarawak

Third WorldQuarterly, Vol21, No 6, pp 977 – 988, 2000 Globalizationand democratization: the responseo ftheindigenous peoples o f Sarawak SABIHAHOSMAN ABSTRACT Globalizationis amulti-layered anddialectical process involving two consequenttendencies— homogenizing and particularizing— at the same time. Thequestion of howand in whatways these contendingforces operatein Sarawakand in Malaysiaas awholeis therefore crucial in aneffort to capture this dynamic.This article examinesthe impactof globalizationon the democra- tization process andother domestic political activities of the indigenouspeoples (IPs)of Sarawak.It shows howthe democratizationprocess canbe anempower- ingone, thus enablingthe actors to managethe effects ofglobalization in their lives. Thecon ict betweenthe IPsandthe state againstthe depletionof the tropical rainforest is manifested in the form of blockadesand unlawful occu- pationof state landby the former as aform of resistance andprotest. Insome situations the federal andstate governmentshave treated this actionas aserious globalissue betweenthe international NGOsandthe Malaysian/Sarawakgovern- ment.In this case globalizationhas affected boththe nation-state andthe IPs in different ways.Globalization has triggered agreater awareness of self-empow- erment anddemocratization among the IPs. These are importantforces in capturingsome aspects of globalizationat the local level. Globalization is amulti-layered anddialectical process involvingboth homoge- nization andparticularization, ie the rise oflocalism in politics, economics, -

Borneo Research Bulletin, Deparunenr

RESEAR BULLETIN --1. 7, NO. 2 September -1975 Notes From the Editor: Appreciation to Donald E. Brown; Contributions for the support of the BRC; Suggestions for future issues; List of Fellows ................... 4 4 Research Notes Distribution of Penan and Punan in the Belaga District ................Jay1 Langub 45 Notes on the Kelabit ........... Mady Villard 49 The Distribution of Secondary Treatment of the Dead in Central North mrneo ...Peter Metcalf 54 Socio-Ecological Sketch of Two Sarawak Longhouses ............. Dietrich Kuhne i 60 Brief Communications The Rhinoceros and Mammal Extinction in General ...............Tom Harrisson 71 News and Announcements ! Mervyn Aubrey Jaspan, 1926-1975. An Obituary ............... Tom Harrisson Doctoral Dissertations on Asia .... Frank J. Shulman Borneo News .................... Book Reviews, Abstracts and Bibliography Tom Harrisson: Prehistoric Wood from Brunei, Borneo. (Barbara Harrisson) ............ Michael and Patricia Fogden: Animals and Their Colours. (Tom Harrisson) ...... Elliott McClure: Migration and Survival of the Birds of Asia. (Tom Harrisson) .... The Borneo Research Bullt e yearly (A and September) by the 601 Please ad all inquiries and contribut:ons ror pwllcacioln to Vinson bUC- 'live, Editor, Borneo Research Bulletin, Deparunenr... or Anthropology. College of William ant liamsburg, 'Virginia 231 85. U.S.A. Single isaiues are ave JSS?.50. 14- -45- 1 kak Reviews, Abstracts and Biblioqraphy (cont.) RESEARCH NOTES Sevinc Carlson: Malaysia: Search for National Unity and Economic Growth .............................. 7 9 DISTRIBUTION OF PENAN AND PUNAN IN THE: BELAGA DISTRICT Robert Reece: The Cession of Sarawak to the British Crown in 1946 . ' Jay1 Langub Joan Seele,r: Kenyah A Description and ' I S.... ...........80 hy ... ........... 80 After reading the reports on the Punan in Kalimantan by Victor xing and H.L. -

The Dominant Anopheles Vectors of Human Malaria in the Asia-Pacific

Sinka et al. Parasites & Vectors 2011, 4:89 http://www.parasitesandvectors.com/content/4/1/89 RESEARCH Open Access The dominant Anopheles vectors of human malaria in the Asia-Pacific region: occurrence data, distribution maps and bionomic précis Marianne E Sinka1*, Michael J Bangs2, Sylvie Manguin3, Theeraphap Chareonviriyaphap4, Anand P Patil1, William H Temperley1, Peter W Gething1, Iqbal RF Elyazar5, Caroline W Kabaria6, Ralph E Harbach7 and Simon I Hay1,6* Abstract Background: The final article in a series of three publications examining the global distribution of 41 dominant vector species (DVS) of malaria is presented here. The first publication examined the DVS from the Americas, with the second covering those species present in Africa, Europe and the Middle East. Here we discuss the 19 DVS of the Asian-Pacific region. This region experiences a high diversity of vector species, many occurring sympatrically, which, combined with the occurrence of a high number of species complexes and suspected species complexes, and behavioural plasticity of many of these major vectors, adds a level of entomological complexity not comparable elsewhere globally. To try and untangle the intricacy of the vectors of this region and to increase the effectiveness of vector control interventions, an understanding of the contemporary distribution of each species, combined with a synthesis of the current knowledge of their behaviour and ecology is needed. Results: Expert opinion (EO) range maps, created with the most up-to-date expert knowledge of each DVS distribution, were combined with a contemporary database of occurrence data and a suite of open access, environmental and climatic variables. -

Dewan Rakyat Parlimen Ketiga Belas Penggal Pertama Mesyuarat Ketiga

Naskhah belum disemak DEWAN RAKYAT PARLIMEN KETIGA BELAS PENGGAL PERTAMA MESYUARAT KETIGA Bil. 46 Rabu 27 November 2013 K A N D U N G A N JAWAPAN-JAWAPAN LISAN BAGI PERTANYAAN-PERTANYAAN (Halaman 1) USUL MENANGGUHKAN MESYUARAT DI BAWAH P.M. 18(1): ■ Tuntutan Coalition of Malaysia NGOs (Comango) Bertentangan Dengan Agama Islam dan Perlembagaan Persekutuan - Datuk Seri Haji Noh bin Omar (Tanjong Karang) (Halaman 25) RANG UNDANG-UNDANG: Rang Undang-undang Perbekalan 2014 Jawatankuasa:- Jadual:- B.32 (Halaman 29) B.20 (Halaman 98) B.42 (Halaman 128) USUL-USUL: Waktu Mesyuarat dan Urusan Dibebaskan Daripada Peraturan Mesyuarat (Halaman 28) Usul Anggaran Pembangunan 2014 Jawatankuasa:- P.32 (Halaman 29) P.20 (Halaman 98) P.42 (Halaman 128) DR.27.11.2013 1 MALAYSIA DEWAN RAKYAT PARLIMEN KETIGA BELAS PENGGAL PERTAMA MESYUARAT KETIGA Rabu, 27 November 2013 Mesyuarat dimulakan pada pukul 10.00 pagi DOA [Timbalan Yang di-Pertua (Datuk Ronald Kiandee) mempengerusikan Mesyuarat] JAWAPAN-JAWAPAN LISAN BAGI PERTANYAAN-PERTANYAAN 1. Dato' Seri Tiong King Sing [Bintulu] minta Perdana Menteri menyatakan: (a) adakah pihak kerajaan berhasrat untuk menaik taraf pusat pentadbiran, pangkalan, peralatan dengan kediaman bagi Agensi Penguatkuasaan Maritim Malaysia di Bintulu, Sarawak pada masa terdekat ini; dan (b) sejauh manakah keberkesanan agensi ini menjalankan tugasan operasi semenjak ditubuhkan beberapa tahun yang lalu dari segi tangkapan, pencegahan dan lain-lain. Menteri di Jabatan Perdana Menteri [Dato' Seri Shahidan bin Kassim]: Bismillahi Rahmani Rahim. Semoga Allah merahmati mereka yang menonton siaran ini. Tuan Yang di-Pertua, Agensi Penguatkuasaan Maritim Malaysia (APMM) telah mula beroperasi di Bintulu pada 1 Oktober 2008 dengan menggunakan bangunan yang disewa daripada Pejabat Maritim Daerah Bintulu. -

Action Items

International President’s Appeal Women, Water and Leadership (WWL) Update on Projects supported – December 2018 Five projects have been selected to benefit from funds raised by the four Federations in support of the International President’s Appeal 2017-2019, “Women Water and Leadership” (WWL). The following is an update on the amount raised and what has taken place for each project by the end of the first year. Funds raised by the four Federations in Year 1 of the 2 year Appeal Donations through Federations amount to £ 138,856 SIGBI raised £19,685 SI Europe raised £31,300 SI South West Pacific raised £14,071 SI Americas raised £73,800 In addition, there have been several private donations (not made through the Federation HQ) which amount to £55,685, plus £12,000 made from the sale of pins and pendants, making the total raised at the end of the first year £206,541. Project 1 – Continent Africa – Kenya – SI Union Kenya “Mwihoko Women Group”. As the area was hit by a very bad weather which affected the crop severely a Field Day on 29th of November had to be cancelled to a later date during the rainy season in 2019. The plan is to showcase the project to the community and stakeholders. Part of the activities that day will be presentation of certificates to the farmer members of the first group who were trained in Egerton University. Other partners and suppliers will also be showcasing their products and services. Project 2 - Continent Europe – Bulgaria – Earth Forever together with SI club Plovdiv “WeWash (Women empowerment through water, sanitation and health)”. -

Dewan Rakyat

Bil. 46 Rabu 27 November 2013 MALAYSIA PENYATA RASMI PARLIMEN DEWAN RAKYAT PARLIMEN KETIGA BELAS PENGGAL PERTAMA MESYUARAT KETIGA K A N D U N G A N JAWAPAN-JAWAPAN LISAN BAGI PERTANYAAN-PERTANYAAN (Halaman 1) USUL MENANGGUHKAN MESYUARAT DI BAWAH P.M. 18(1): ■ Tuntutan Coalition of Malaysia NGOs (Comango) Bertentangan Dengan Agama Islam dan Perlembagaan Persekutuan - Datuk Seri Haji Noh bin Omar (Tanjong Karang) (Halaman 20) RANG UNDANG-UNDANG: Rang Undang-undang Perbekalan 2014 Jawatankuasa:- Jadual:- B.32 (Halaman 23) B.20 (Halaman 78) B.42 (Halaman 101) USUL-USUL: Waktu Mesyuarat dan Urusan Dibebaskan Daripada Peraturan Mesyuarat (Halaman 22) Anggaran Pembangunan 2014 Jawatankuasa:- P.32 (Halaman 23) P.20 (Halaman 78) P.42 (Halaman 101) Diterbitkan Oleh: CAWANGAN PENYATA RASMI PARLIMEN MALAYSIA 2013 DR.27.11.2013 i AHLI-AHLI DEWAN RAKYAT 1. Yang Berhormat Tuan Yang di-Pertua, Tan Sri Datuk Seri Panglima Pandikar Amin Haji Mulia, P.S.M., S.P.D.K., S.U.M.W., P.G.D.K., J.S.M., J.P. 2. “ Timbalan Yang di-Pertua, Datuk Ronald Kiandee, P.G.D.K., A.S.D.K. [Beluran] - UMNO 3. “ Timbalan Yang di-Pertua, Dato’ Haji Ismail bin Haji Mohamed Said, D.I.M.P., S.M.P., K.M.N. [Kuala Krau] - UMNO MENTERI 1. Yang Amat Berhormat Perdana Menteri dan Menteri Kewangan I, Dato’ Sri Mohd. Najib bin Tun Abdul Razak, Orang Kaya Indera Shah Bandar, S.P.D.K., S.S.A.P., S.S.S.J., S.I.M.P., D.P.M.S., D.S.A.P., P.N.B.S. -

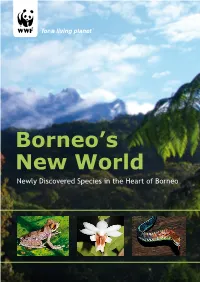

Borneo's New World

Borneo’s New World Newly Discovered Species in the Heart of Borneo Dendrelaphis haasi, a new snake species discovered in 2008 © Gernot Vogel © Gernot WWF’s Heart of Borneo Vision With this report, WWF’s Initiative in support of the Heart of Borneo recognises the work of scientists The equatorial rainforests of the Heart and researchers who have dedicated countless hours to the discovery of of Borneo are conserved and effectively new species in the Heart of Borneo, managed through a network of protected for the world to appreciate and in its areas, productive forests and other wisdom preserve. sustainable land-uses, through cooperation with governments, private sector and civil society. Cover photos: Main / View of Gunung Kinabalu, Sabah © Eric in S F (sic); © A.Shapiro (WWF-US). Based on NASA, Visible Earth, Inset photos from left to right / Rhacophorus belalongensis © Max Dehling; ESRI, 2008 data sources. Dendrobium lohokii © Amos Tan; Dendrelaphis kopsteini © Gernot Vogel. A declaration of support for newly discovered species In February 2007, an historic Declaration to conserve the Heart of Borneo, an area covering 220,000km2 of irreplaceable rainforest on the world’s third largest island, was officially signed between its three governments – Brunei Darussalam, Indonesia and Malaysia. That single ground breaking decision taken by the three through a network of protected areas and responsibly governments to safeguard one of the most biologically managed forests. rich and diverse habitats on earth, was a massive visionary step. Its importance is underlined by the To support the efforts of the three governments, WWF number and diversity of species discovered in the Heart launched a large scale conservation initiative, one that of Borneo since the Declaration was made. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2011 HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION of MALAYSIA First Printing, 2012

ANNUAL REPORT 2011 HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION OF MALAYSIA First Printing, 2012 © Copyright Human Rights Commission of Malaysia (SUHAKAM) The copyright of this report belongs to the Commission. All or any part of this report may be reproduced provided acknowledgement of source is made or with the Commission’s permission. The Commission assumes no responsibility, warranty and liability, expressed or implied by the reproduction of this publication done without the Commission’s permission. Notification of such use is required. All rights reserved. Published in Malaysia by HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION OF MALAYSIA 11th Floor, Menara TH Perdana 1001, Jalan Sultan Ismail, 50250 Kuala Lumpur Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.suhakam.org.my Designed & Printed in Malaysia by Reka Cetak Sdn Bhd No. 14, Jalan Jemuju Empat 16/13D Seksyen 16, 40200 Shah Alam Selangor Darul Ehsan National Library of Malaysia Cataloguing-in-Publication Data ISBN: 1675-1159 MEMBERS OF THE COMMISSION 2011 STANDING FROM LEFT PROF DATO’ DR MAHMOOD ZUHDI HJ AB MAJID, MR JAMES NAYAGAM, MS JANNIE LASIMBANG, MR MUHAMMAD SHA’ANI ABDULLAH, MR DETTA SAMEN SEATED FROM LEFT PROF DATUK DR KHAW LAKE TEE (Vice-Chairman), TAN SRI HASMY AGAM (Chairman), MRS HASHIMAH NIK JAAFAR (Secretary) HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION OF MALAYSIA ANNUAL REPORT 2011 CONTENTS CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 7 KEY ISSUES 13 CHAPTER 1 REPORT OF THE EDUCATION AND PROMOTION WORKING GROUP 23 CHAPTER 2 REPORT OF THE COMPLAINTS AND INQUIRIES WORKING GROUP 39 CHAPTER 3 REPORT OF THE LAW REFORM AND INTERNATIONAL