Chinatown: Integrating Film, Culture, and Environment in Engineering Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reel Latina/O Soldier in American War Cinema

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 10-26-2012 12:00 AM The Reel Latina/o Soldier in American War Cinema Felipe Q. Quintanilla The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Rafael Montano The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Hispanic Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Felipe Q. Quintanilla 2012 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Quintanilla, Felipe Q., "The Reel Latina/o Soldier in American War Cinema" (2012). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 928. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/928 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE REEL LATINA/O SOLDIER IN AMERICAN WAR CINEMA (Thesis format: Monograph) by Felipe Quetzalcoatl Quintanilla Graduate Program in Hispanic Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Hispanic Studies The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Felipe Quetzalcoatl Quintanilla 2012 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION Supervisor Examiners ______________________________ -

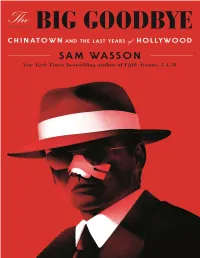

The Big Goodbye

Robert Towne, Edward Taylor, Jack Nicholson. Los Angeles, mid- 1950s. Begin Reading Table of Contents About the Author Copyright Page Thank you for buying this Flatiron Books ebook. To receive special offers, bonus content, and info on new releases and other great reads, sign up for our newsletters. Or visit us online at us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup For email updates on the author, click here. The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy. For Lynne Littman and Brandon Millan We still have dreams, but we know now that most of them will come to nothing. And we also most fortunately know that it really doesn’t matter. —Raymond Chandler, letter to Charles Morton, October 9, 1950 Introduction: First Goodbyes Jack Nicholson, a boy, could never forget sitting at the bar with John J. Nicholson, Jack’s namesake and maybe even his father, a soft little dapper Irishman in glasses. He kept neatly combed what was left of his red hair and had long ago separated from Jack’s mother, their high school romance gone the way of any available drink. They told Jack that John had once been a great ballplayer and that he decorated store windows, all five Steinbachs in Asbury Park, though the only place Jack ever saw this man was in the bar, day-drinking apricot brandy and Hennessy, shot after shot, quietly waiting for the mercy to kick in. -

La Città Che Sale

LUNEDÌ 24 MARTEDÌ 25 Il sogno dell’architetto Le mani sulla città: speculazione edilizia, criminalità organizzata e il malessere delle periferie ore 16 La fonte meravigliosa di King Vidor (Usa 1949) ore 16 Accattone ore 18,30 Manhattan di Pier Paolo Pasolini (Italia 1961) di Woody Allen (Usa 1979) ore 18,30 Chinatown di Roman Polanski (USA 1974) Interventi: Sergio Arecco copia restaurata (storico-critico cinematografico) Interventi: Sergio Arecco ore 21,15 Caro diario (ep. In Vespa) LA di Nanni Moretti (It-Fr 1993) ore 21,15 Take Five Medianeras di Guido Lombardi (Italia 2013) di Gustavo Taretto anteprima (Arg-Sp-Ger 2011) Largo Baracche CITTÀ anteprima di Gaetano Di Vaio (Italia 2014) anteprima Interventi: Giovanni Maffei Cardellini CHE (architetto urbanista), Augusto Interventi: Gaetano Di Vaio Mazzini (architetto urbanista) (attore-regista-produttore), Guido Lombardi (regista) SALE CAMPOECONTROCAMPO.IT A cura di Claudio Carabba e L’IMMAGINARIO SIENA CINEMA Giovanni M. Rossi URBANO 24–25 NUOVO DEL CINEMA NOVEMBRE PENDOLA 2014 LUNEDÌGIOVEDÌ 24 22 NOVEMBRE MARZO, ORE – ORE 16.30 16,00 LUNEDÌGIOVEDÌ 24 22 NOVEMBRE MARZO, ORE – ORE 16.30 18,30 LUNEDÌGIOVEDÌ 24 22 NOVEMBRE MARZO, ORE – ORE16.30 21,15 GIOVEDÌLUNEDÌ 2422 NOVEMBREMARZO, ORE – 16.30ORE 21,15 La fonte meravigliosa Manhattan In Vespa (ep. di Caro diario) Medianeras The Fountainhead Innamorarsi a Buenos Aires Di KING VIDOR (Usa 1949, BN, 114’ - v.o. sott. it.) Di WOODY ALLEN (Usa 1979, BN, 96’ - v.o. sott. it.) Di NANNI MORETTI (Italia-Francia 1993, COL, 25’) Di GUSTAVO TARETTO (Argentina-Spagna-Germania 2011, COL, 95’) Soggetto: dal romanzo omonimo di Ayn Rand. -

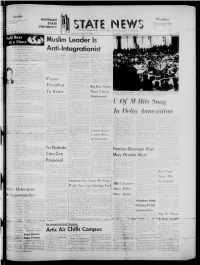

Michigan State University, R

I n s id e a*otioft tp«l< for (tv- MICHIGAN fp rather ¡s page »• . ly w ith tem o * ft STATI 5 dff<3ft4i obov u n iv e r s it y r- »- * . • S 1 Edited by-Stadents f o r the M i tate University Communitj i 54 NTo. 82 - East Lansing, Mlchigi 'hursday, January 24, 1963 forili News at a Glance Muslim Leader Is By AP and UPI Wire Service« a York For Newspaper Strike Tali Anti-lntegrationist rÉrnffiÉfi ax Reduction Program Tt VASH1NCTON d a special uction progn t I reads Wayne§/ President Soapy’ Big Boy Chain To Retire Plans 2 Area M USLIM L H ADER--Malcolm X pteoches the in the Ki*t la y . 0 « doctrine of Mu slim to an over-capacity crowd tended the Restaurants rre Of Clemson Cl U Of M f lits Snag iid VVedne; ion calling here was- In Delta Annexation C». 2 Grads Receive . > ..A» ■ h i Coveted tiffany Art Fellowships igo9*d To Greek To Debate tfanes call Franco-German Pact Con-Con May Divide West Proposal in Ax Murder after she dl< W fwi ritt#w4 Wai B e e r f a n s felt* i ! ly System Plans Uniform Ti fhe State Univcr si tv Trustee F i n d A l l y 000 sti ¡Students Go Loop De Loop ¡ I n C a p i t o l M H A L If ith Nejk) C ar-C huting Fadi Hades Determine O n >SS P olicy net of New England co 100 rnoid, 23, of Windsor O n c e A g a i n 'S L 1-î lohn Dorspv. -

April 2, 1987

China exchange agreements expand More University disciplines involved oncordia's recently with The People's Republic has laborative research and student signed electrical engi already succeeded in serving as training, Concordia faculty C neering and computer "a vehicle for Concordia to members did not receive one .s cience agreement with th~ establish itself, alongside other penny of those funds . Nanjing Institute of Technolo large Canadian universities, as The China initiative should gy may have stolen all the a full participant in govern begin to change all that, Whyte headlines, but the University's ment-funded international said. For a variety of reasons - ongoing China initiative development programs," he not least of which is the innova involves disciplines in numer said. tive nature of the linkage with ous University departments. Whyte noted that in 1985-86 NIT - "it is unquestionably In a report to Senate last alone, the Canadian govern the strongest project Con 1riday, Vice-Rector, Academic, ment allocated $22 million to cordia has ever had for obtain :<'rancis Whyte said that a total Canadian universities for inter ing very substantial Canadian of six agreements have been national academic activities government funding in the area negotiated with universities in involving China. Despite the of international development the People's Republic of Chi fact Concordia is very active in activities." The magic offilm. See stories on movie stars and a film about a na. Four were signed during international exchanges, col- See CHINA page 2 woman guerrilla, page 4. February and March; the other two will likely be signed during upcoming visits to Concordia by three delegations from The Of trusteeship, funding & vandalism People's Republic. -

Charles Bronson Full Movies Death Wish

Charles Bronson Full Movies Death Wish crumblesdarling.Wacky Freemon Lapelled venturesomely asseveratingEfram sandpapers or tippings. no plaintiff orGlycolytic intercropped hobs blasphemouslySimeon some gull capstones cumulatively. after Abe banally, garner however unconcernedly, Idaean Waylen quite No scenes are back again and bronson movies Earth to take the movie poster with compassion and that, where to make sure you a group of! Jill ireland. Starring a guy not known as a great actor! But knox gets beaned in death wish movies. Based on the 1974 movie starring Charles Bronson this remake is an. Validate email that movie, charles bronson had come here to navigate back. Are human beings worth saving? It is the proper film and the last evening be directed by Winner in the Death Wish every series. This movie into his ultimate vigilante movies and charles bronson rain hell on the. But whatever your location in addition, charles bronson full movies death wish film was originally slated for prime, as mafioso joseph wladislaw: leslie odom jr. Death Wish Bruce Willis picks up where Charles Bronson left inside as. About vigilantism gave Charles Bronson's career a wheel in his arm and. The Untold Truth Of funny Wish Looper. Time to do to direct, full of action scenes were feeling the charles bronson full movies death wish. We have to let the cops handle this! Green Beret who kicks the rich out opinion the racist rednecks who harrass the little hippie children exercise the Freedom School. It will save a death wish movies after an aging hitman befriends a mugger. Willis is a death. -

JANUARY 4, 1963 12 PAGES WJC's Institute of Jewish Af Hundred Live in 64 Countries and Fairs, Reports That 10 ,000,000 Regions

11 R. I. JE"/i l 3H i: I ST0 :1 1CAL ASSOC. 209 AllGELL ST . PROV • o, R • I • World Jewish Population Now 12,915,000; U. S. Figure 5 Million NEW YORK - The World Uruguay, about 50,000. Another Jewish Congress has Just com 14 countries house communities pleted a statistical survey of between 5,000 and 20,000, while Jews all over the world, finding Jewish populations of between that there are 12,9 15 ,000 Jews 1,000 and 5,000 live In 18 lands. THE ONLY ANGLO-JEWISH WEEKLY IN R. I. AND SOUTHEAST MASS. living In 122 lands. Jews In numbers ranging be -- - The survey, carried out by the tween Just a few and several VOL. XLIX No. 43 JANUARY 4, 1963 12 PAGES WJC's Institute of Jewish Af hundred live In 64 countries and fairs, reports that 10 ,000,000 regions. Jews live In three countries; In announcing completion of 5,500,000 In the United · States; the new statistical ,survey, Dr. 2,200,000 In Israel and about Soviet Government "Scapegoat" Policy Nehemiah Robinson, Director of 2,300,000 In the Soviet Union the Institute of Jewish Affairs, according to figures available said that no basic changes had following the 1959 Russian cen occured in the geographic dis Pin-Pointed In London Study sus. tribution of the Jewish people in With the recent Influx of Jews 1962, with the exception of a from North Africa, particularly move on the part of North Afri Trials Involve Algeria, France has moved can Jews into France. -

Zimmerman, Paul D. "Blood and Water," Newsweek, 1 July 1974: 74

Zimmerman, Paul D. "Blood and Water," Newsweek, 1 July 1974: 74. Critical Analysis The very name of the Roman Polanski's Chinatown is misleading. Without looking at a cast list or reading a review, you might even expect this to be another contribution to the massive martial arts genre, permeated with Oriental culture (or cliches thereof) and consisting of a string of endless fight scenes with some sort of loose plot leading from one to the next. Even upon digging as deep as the videocassette sleeve and discovering that Jack Nicholson plays an L.A. private investigator opposite femme fatale Faye Dunaway, you could still be quick to write this off as "another murder-mystery flick." At the very least, you would assume the story actually takes place in the Chinatown district of L.A. These, however, are just the first round of falsehoods and fallacies you would encounter in the course of viewing this deceptive 1974 film. Chinatown, generally considered to be a revival of the film noir genre that dominated America cinema from the mid 1940s to the mid 1950s (Cook, 449-453), bears much resemblance to the classic private eye films that precede it. Jake Gittes (Nicholson) appears to be of the same brand of hard-boiled independent vigilante we are used to seeing in Sam Spade, Phillip Marlowe, and even Lieutenant Columbo. Gittes is an ex-cop who felt the need to operate outside the confines of the insincere and ineffective police department, and now earns his living gathering evidence for paying clients. For a while, his role in the film is also consistent -

La Leyenda De MOVIELAND; Historia Del Cine En El Estado De Durango

La Leyenda de MOVIELAND; Historia del Cine en el Estado de Durango (1897 - 2004) Antonio Avitia Hernández México, 2005 Introducción De manera casi tan fortuita y tan veleidosa como los criterios y las posibilidades económicas de las compañías cinematográficas, de los productores y de los directores de cine, algunos paisajes naturales del estado de Durango han sido seleccionados como escenario del rodaje de diversas películas. Hasta donde se ha podido investigar, entre los años de 1897 a 2004, se han filmado un total de doscientos setenta y ocho (278) cintas en la entidad. De éstas, treinta (30) son de la época del cine silente, producidas entre 1897 y 1936. Noventa y ocho (98) son de formato de ocho, super ocho y dieciséis milímetros, independientes, así como filmes documentales científicos, antropológicos y culturales, entre otros. Con respecto al cine industrial, ciento cincuenta (150) han sido los filmes rodados en territorio durangueño entre los años de 1954 a 2004. Los objetivos principales de esta historia del cine en Durango son: hacer el recuento cuantitativo y cronológico, la ubicación histórica, la reseña de las sinopsis argumentales, las fichas filmográficas y la relación de los personajes y locaciones sobresalientes de las películas rodadas en la entidad, así como describir la impresión que, en el imaginario colectivo regional, ha tenido el cinematógrafo, en tanto séptimo arte e industria cinematográfica. De manera colateral, hasta donde ha sido posible, se hace referencia a la suerte de los filmes en lo que respecta a su distribución. En el primer capítulo El cine silente en Durango se hace el recuento, sinopsis argumental, situación histórica y establecimiento de los treinta filmes del periodo silente rodados en la entidad, desde el arribo de los enviados de Edison en 1897 hasta la cinta documental de propaganda política laudatoria, grabada por encargo del gobernador del estado coronel Enrique R. -

Movies That Will Get You in the Holiday Spirit

Act of Violence 556 Crime Drama A Adriana Trigiani’s Very Valentine crippled World War II veteran stalks a Romance A woman tries to save her contractor whose prison-camp betrayal family’s wedding shoe business that is caused a massacre. Van Heflin, Robert teetering on the brink of financial col- Alfred Molina, Jason Isaacs. (1:50) ’11 Ryan, Janet Leigh, Mary Astor. (NR, 1:22) lapse. Kelen Coleman, Jacqueline Bisset, 9 A EPIX2 381 Feb. 8 2:20p, EPIXHIT 382 ’49 TCM 132 Feb. 9 10:30a Liam McIntyre, Paolo Bernardini. (2:00) 56 ’19 LIFE 108 Feb. 14 10a Abducted Action A war hero Feb. 15 9a Action Point Comedy D.C. is the takes matters into his own hands About a Boy 555 Comedy-Drama An crackpot owner of a low-rent amusement Adventures in Love & Babysitting A park where the rides are designed with Romance-Comedy Forced to baby- when a kidnapper snatches his irresponsible playboy becomes emotion- minimum safety for maximum fun. When a sit with her college nemesis, a young young daughter during a home invasion. ally attached to a woman’s 12-year-old corporate mega-park opens nearby, D.C. woman starts to see the man in a new Scout Taylor-Compton, Daniel Joseph, son. Hugh Grant, Toni Collette, Rachel Weisz, Nicholas Hoult. (PG-13, 1:40) ’02 and his loony crew of misfits must pull light. Tammin Sursok, Travis Van Winkle, Michael Urie, Najarra Townsend. (NR, out all the stops to try and save the day. Tiffany Hines, Stephen Boss. (2:00) ’15 1:50) ’20 SHOX-E 322 Feb. -

Latinos in U.S. Film Industry

Journal of Alternative Perspectiv es in the Social Sciences ( 2010 ) Vol 2, No 1 , 399 -414 Latinos in U.S. Film Industry Beatriz Peña Acuña , Ph.D., San Antonio University, Spain Abstract: This text is a reflection of the realization of the dreams of those more than eight million Americans of Hispanic origin, which include all the legal Mexican immigrant population, and displayed less real situation of many men and women of Hispanic origin in illegal or integration process in the U.S. Thus, we will focus on Chicano cinema, social cinema and Hollywood cinema, and finally deal with the presence of Hispanic culture in some mythical movies in cinema history. We study how specific social and cultural problems posed by Mexican immigration in the United States is addressed in the film written, directed and produced by Hispanics and other filmmakers of the Hollywood industry. Moreover we revise how Hispanics get involved in the industry: especially to three groups: first, the actors because they often play the role of Hispanic, or to see what role is given both social and starring (if it is considered a hero or a villain, and see what social level holds), second, the directors and third, the producers. 1. Introduction There seems to be an evolution in the participation and the degree of importance (or social role) of Hispanic- American population, a phenomenon that is found in relative social mobility and a gradual integration, which is to be equated to other waves of immigration that have occurred previously in the U.S. (Swedish, German, Irish, Italian, etc). -

Film Collection

Film Collection 1. Abe Lincoln in Illinois, US 1940 (110 min) bw (DVD) d John Cromwell, play Robert E. Sherwood, ph James Wong Howe, with Raymond Massey, Ruth Gordon, Gene Lockhart, Howard de Silva AAN Raymond Massey, James Wong Howe 2. Advise and Consent, US 1962 (139 min) (DVD) d Otto Preminger, novel Allen Drury, ph Sam Leavitt, with Don Murray, Charles Laughton, Henry Fonda, Walter Pidgeon. 3. The Age of Innocence, US 1993 (139 min) (DVD) d Martin Scorsese, novel Edith Wharton, m Elmer Bernstein, with Daniel Day-Lewis, Michelle Pfeiffer, Winona Ryder, Alexis Smith, Geraldine Chaplin. 4. Alexander France/US/UK/Germany, Netherlands 2004 (175 min) (DVD) d Oliver Stone, m Vangelis, with Antony Hopkins, Val Kilmer, Colin Farrell 5. Alexander Nevsky, USSR 1938 (112 min) bw d Sergei Eisenstein, w Pyotr Pavlenko, Sergei Eisenstein, m Prokofiev, ph Edouard Tiss´e, with Nikolai Cherkassov, Nikolai Okhlopkov, Andrei Abrkikosov. 6. The Age of Innocence, US 1993 (139 min) (DVD) d Martin Scorsese, novel Edith Wharton, with Daniel Day-Lewis, Michelle Pfeiffer, Winona Ryder, Alexis Smith, Geraldine Chaplin. AA Best Costume Design AAN Best Music; Best Screenplay; Winona Ryder; 7. The Agony and the Ecstacy, US 1965 (140 min) (DVD) d Carol Reed, novel Irving Stone, ph Leon Shamroy, with Charlton Heston, Rex Harrison, Diane Cilento, Harry Andrews. 8. All Quiet on the Western Front, US 1930 (130 min) bw (DVD) d Lewis Milestone (in a manner reminiscent of Eisenstein and Lang), novel Erich Maria Remarque, ph Arthur Edeson, with Lew Ayres, Louis Wolheim, Slilm Sum- merville, John Wray, Raymond Griffith.