'Either You Bring the Water to L.A. Or You Bring L.A. To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gangster Squad :: Rogerebert.Com :: Reviews

movie reviews Reviews Great Movies Answer Man People Commentary Festivals Oscars Glossary One-Minute Reviews Letters Roger Ebert's Journal Scanners Store News Sports Business Entertainment Classifieds Columnists search GANGSTER SQUAD (R) Ebert: Users: You: Rate this movie right now GO Search powered by YAHOO! register You are not logged in. Log in » Subscribe to weekly newsletter » times & tickets in theaters Fandango Search movie more current releases » showtimes and buy Gangster Squad tickets. one-minute movie reviews by Jeff Shannon / January 9, 2013 still playing about us You may have noticed that the trailers for "Gangster About the site » Squad" are peppered with cast & credits The Loneliest Planet hyperbolic review quotes 56 Up Site FAQs » provided by syndicated Sean Penn Mickey Cohen Amour Beautiful Creatures critics of dubious merit. Josh Brolin Sgt. John O'Mara Contact us » Bless Me, Ultima They're a sure sign of a Ryan Gosling Sgt. Jerry Wooters Broken City movie's mediocrity, and my Emma Stone Grace Faraday Email the Movie Bullet to the Head favorite blurb hypes Answer Man » Mireille Enos Connie O'Mara Consuming Spirits "Gangster Squad" as "the Nick Nolte Chief Parker Dark Skies best gangster film of the Robert Patrick Officer Max Kennard Everybody in Our Family on sale now decade!!" Man, what a drag. Giovanni Ribisi Officer Conway Future Weather If that's true, the next seven Gangster Squad Keeler years are going to be lousy The Gatekeepers Michael Peña Officer Navidad for the world's favorite crime A Glimpse Inside the Mind of Charles Swan III genre. Ramirez A Good Day to Die Hard Happy People: A Year in the Taiga To be fair, this tawdry dose Warner Bros. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Beer Blood and Ashes by Michael Madsen Mr Blonde's Ambition

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Beer Blood and Ashes by Michael Madsen Mr Blonde's ambition. A fortnight before the American release of Quentin Tarantino's Kill Bill Vol 2, its star, Michael Madsen, sits on the upper deck of his Malibu beach home, smoking Chesterfields and watching the dolphins. There are four in the distance, jumping happy arcs through the waves. This morning, though, they're the only ones leaping for joy. 'It's hard, man. I got a big overhead,' says the actor, shaking his head. 'I'm taking care of three different families at the moment. There's my ex- wife, then my mom and my niece. And then there's all this.' He indicates the four-bedroom house behind him where he lives with his third wife and his five sons. It's a great place - bright, white and tall, every wall filled with old movie posters, lovingly framed. He bought it from Ted Danson, who bought it from Walt Disney's daughter, who bought it from the man who built it - Keith Moon of The Who. Since the boys are at school (the eldest is 16) the house is relatively quiet. Besides the whoosh of the Pacific on to his private beach below, all you can hear is his beautiful wife Deanna on the phone in the kitchen, his parrot Marlon squawking merrily downstairs, and Madsen's own quiet, whisky rasp, bemoaning his hard times. 'I'm trying to downscale,' he says. 'I already let two of my motorcycles go and I sold three of my cars - a Corvette, a little Porsche that I had and a '57 Chevy.' He sighs and shrugs. -

The Reel Latina/O Soldier in American War Cinema

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 10-26-2012 12:00 AM The Reel Latina/o Soldier in American War Cinema Felipe Q. Quintanilla The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Rafael Montano The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Hispanic Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Felipe Q. Quintanilla 2012 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Quintanilla, Felipe Q., "The Reel Latina/o Soldier in American War Cinema" (2012). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 928. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/928 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE REEL LATINA/O SOLDIER IN AMERICAN WAR CINEMA (Thesis format: Monograph) by Felipe Quetzalcoatl Quintanilla Graduate Program in Hispanic Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Hispanic Studies The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Felipe Quetzalcoatl Quintanilla 2012 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION Supervisor Examiners ______________________________ -

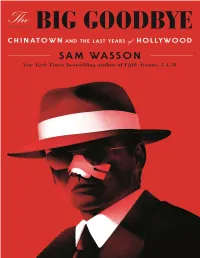

The Big Goodbye

Robert Towne, Edward Taylor, Jack Nicholson. Los Angeles, mid- 1950s. Begin Reading Table of Contents About the Author Copyright Page Thank you for buying this Flatiron Books ebook. To receive special offers, bonus content, and info on new releases and other great reads, sign up for our newsletters. Or visit us online at us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup For email updates on the author, click here. The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy. For Lynne Littman and Brandon Millan We still have dreams, but we know now that most of them will come to nothing. And we also most fortunately know that it really doesn’t matter. —Raymond Chandler, letter to Charles Morton, October 9, 1950 Introduction: First Goodbyes Jack Nicholson, a boy, could never forget sitting at the bar with John J. Nicholson, Jack’s namesake and maybe even his father, a soft little dapper Irishman in glasses. He kept neatly combed what was left of his red hair and had long ago separated from Jack’s mother, their high school romance gone the way of any available drink. They told Jack that John had once been a great ballplayer and that he decorated store windows, all five Steinbachs in Asbury Park, though the only place Jack ever saw this man was in the bar, day-drinking apricot brandy and Hennessy, shot after shot, quietly waiting for the mercy to kick in. -

Elmer Bernstein Elmer Bernstein

v7n2cov 3/13/02 3:03 PM Page c1 ORIGINAL MUSIC SOUNDTRACKS FOR MOTION PICTURES AND TV V OLUME 7, NUMBER 2 OSCARmania page 4 THE FILM SCORE HISTORY ISSUE RICHARD RODNEY BENNETT Composing with a touch of elegance MIKLMIKLÓSÓS RRÓZSAÓZSA Lust for Life in his own words DOWNBEAT DOUBLE John Q & Frailty PLUS The latest DVD and CD reviews HAPPY BIRTHDAY ELMER BERNSTEIN 50 years of film scores, 80 years of exuberance! 02> 7225274 93704 $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada v7n2cov 3/13/02 3:03 PM Page c2 composers musicians record labels music publishers equipment manufacturers software manufacturers music editors music supervisors music clear- Score with ance arrangers soundtrack our readers. labels contractors scoring stages orchestrators copyists recording studios dubbing prep dubbing rescoring music prep scoring mixers Film & TV Music Series 2002 If you contribute in any way to the film music process, our four Film & TV Music Special Issues provide a unique marketing opportunity for your talent, product or service throughout the year. Film & TV Music Spring Edition: April 23, 2002 Film & TV Music Summer Edition: August 20, 2002 Space Deadline: April 5 | Materials Deadline: April 11 Space Deadline: August 1 | Materials Deadline: August 7 Film & TV Music Fall Edition: November 5, 2002 Space Deadline: October 18 | Materials Deadline: October 24 LA Judi Pulver (323) 525-2026, NY John Troyan (646) 654-5624, UK John Kania +(44-208) 694-0104 www.hollywoodreporter.com v7n02 issue 3/13/02 5:16 PM Page 1 CONTENTS FEBRUARY 2002 departments 2 Editorial The Caviar Goes to Elmer. 4News Williams Conducts Oscar, More Awards. -

Mulholland Falls

Mulholland Falls THIS ISN’T AMERICA, cumb to its pleasures, and there are (for which he won the Oscar), and many THIS IS LOS ANGELES many. The performances are all wonder - others. Everyone has their favorite ful, the direction hits the right marks, and Grusin scores, and Mulholland Falls is Sometimes it’s just timing. Sometimes the story is compellingly told. mine. Not only does his music do every - it’s just the luck of the draw. In 1996, an thing that film music is supposed to do, LA film noir called Mulholland Falls was Roger Ebert really liked the film, saying, i.e. propel the film, establish its moods, released. Very much attempting to tap “This is the kind of movie where every define its characters, and illuminate its into the feel of the film Chinatown , it re - note is put in lovingly. It’s a 1950s crime story, but apart from the film it is a great ceived some good reviews and some movie, but with a modern, ironic edge.” listening experience – its themes are bad reviews; but not many people cared The Los Angeles Times ’ Kenneth Turan beautiful and memorable, exciting and to see a period LA film noir set in the also liked it, and said, “Mulholland Falls melancholy, mysterious and smoky and early 1950s in 1996, despite its excellent combines a vivid sense of place with a intoxicating. In fact, it’s one of the best cast, which included Nick Nolte, Chaz visceral directorial style that fuses con - noir scores ever written, and right up Palminteri, Jennifer Connelly, John trolled fury onto everything it touches.” there with other classics of the post- Malkovich, Melanie Griffith, Chris Penn, The New York Times’ Janet Maslin, de - 1970s noir scores, Chinatown (Jerry Michael Madsen, Andrew McCarthy, and spite her concerns about the story itself, Goldsmith), Farewell, My Lovely (David Treat Williams, as well as small roles lauded the film: “Mr. -

La Città Che Sale

LUNEDÌ 24 MARTEDÌ 25 Il sogno dell’architetto Le mani sulla città: speculazione edilizia, criminalità organizzata e il malessere delle periferie ore 16 La fonte meravigliosa di King Vidor (Usa 1949) ore 16 Accattone ore 18,30 Manhattan di Pier Paolo Pasolini (Italia 1961) di Woody Allen (Usa 1979) ore 18,30 Chinatown di Roman Polanski (USA 1974) Interventi: Sergio Arecco copia restaurata (storico-critico cinematografico) Interventi: Sergio Arecco ore 21,15 Caro diario (ep. In Vespa) LA di Nanni Moretti (It-Fr 1993) ore 21,15 Take Five Medianeras di Guido Lombardi (Italia 2013) di Gustavo Taretto anteprima (Arg-Sp-Ger 2011) Largo Baracche CITTÀ anteprima di Gaetano Di Vaio (Italia 2014) anteprima Interventi: Giovanni Maffei Cardellini CHE (architetto urbanista), Augusto Interventi: Gaetano Di Vaio Mazzini (architetto urbanista) (attore-regista-produttore), Guido Lombardi (regista) SALE CAMPOECONTROCAMPO.IT A cura di Claudio Carabba e L’IMMAGINARIO SIENA CINEMA Giovanni M. Rossi URBANO 24–25 NUOVO DEL CINEMA NOVEMBRE PENDOLA 2014 LUNEDÌGIOVEDÌ 24 22 NOVEMBRE MARZO, ORE – ORE 16.30 16,00 LUNEDÌGIOVEDÌ 24 22 NOVEMBRE MARZO, ORE – ORE 16.30 18,30 LUNEDÌGIOVEDÌ 24 22 NOVEMBRE MARZO, ORE – ORE16.30 21,15 GIOVEDÌLUNEDÌ 2422 NOVEMBREMARZO, ORE – 16.30ORE 21,15 La fonte meravigliosa Manhattan In Vespa (ep. di Caro diario) Medianeras The Fountainhead Innamorarsi a Buenos Aires Di KING VIDOR (Usa 1949, BN, 114’ - v.o. sott. it.) Di WOODY ALLEN (Usa 1979, BN, 96’ - v.o. sott. it.) Di NANNI MORETTI (Italia-Francia 1993, COL, 25’) Di GUSTAVO TARETTO (Argentina-Spagna-Germania 2011, COL, 95’) Soggetto: dal romanzo omonimo di Ayn Rand. -

Michigan State University, R

I n s id e a*otioft tp«l< for (tv- MICHIGAN fp rather ¡s page »• . ly w ith tem o * ft STATI 5 dff<3ft4i obov u n iv e r s it y r- »- * . • S 1 Edited by-Stadents f o r the M i tate University Communitj i 54 NTo. 82 - East Lansing, Mlchigi 'hursday, January 24, 1963 forili News at a Glance Muslim Leader Is By AP and UPI Wire Service« a York For Newspaper Strike Tali Anti-lntegrationist rÉrnffiÉfi ax Reduction Program Tt VASH1NCTON d a special uction progn t I reads Wayne§/ President Soapy’ Big Boy Chain To Retire Plans 2 Area M USLIM L H ADER--Malcolm X pteoches the in the Ki*t la y . 0 « doctrine of Mu slim to an over-capacity crowd tended the Restaurants rre Of Clemson Cl U Of M f lits Snag iid VVedne; ion calling here was- In Delta Annexation C». 2 Grads Receive . > ..A» ■ h i Coveted tiffany Art Fellowships igo9*d To Greek To Debate tfanes call Franco-German Pact Con-Con May Divide West Proposal in Ax Murder after she dl< W fwi ritt#w4 Wai B e e r f a n s felt* i ! ly System Plans Uniform Ti fhe State Univcr si tv Trustee F i n d A l l y 000 sti ¡Students Go Loop De Loop ¡ I n C a p i t o l M H A L If ith Nejk) C ar-C huting Fadi Hades Determine O n >SS P olicy net of New England co 100 rnoid, 23, of Windsor O n c e A g a i n 'S L 1-î lohn Dorspv. -

April 2, 1987

China exchange agreements expand More University disciplines involved oncordia's recently with The People's Republic has laborative research and student signed electrical engi already succeeded in serving as training, Concordia faculty C neering and computer "a vehicle for Concordia to members did not receive one .s cience agreement with th~ establish itself, alongside other penny of those funds . Nanjing Institute of Technolo large Canadian universities, as The China initiative should gy may have stolen all the a full participant in govern begin to change all that, Whyte headlines, but the University's ment-funded international said. For a variety of reasons - ongoing China initiative development programs," he not least of which is the innova involves disciplines in numer said. tive nature of the linkage with ous University departments. Whyte noted that in 1985-86 NIT - "it is unquestionably In a report to Senate last alone, the Canadian govern the strongest project Con 1riday, Vice-Rector, Academic, ment allocated $22 million to cordia has ever had for obtain :<'rancis Whyte said that a total Canadian universities for inter ing very substantial Canadian of six agreements have been national academic activities government funding in the area negotiated with universities in involving China. Despite the of international development the People's Republic of Chi fact Concordia is very active in activities." The magic offilm. See stories on movie stars and a film about a na. Four were signed during international exchanges, col- See CHINA page 2 woman guerrilla, page 4. February and March; the other two will likely be signed during upcoming visits to Concordia by three delegations from The Of trusteeship, funding & vandalism People's Republic. -

Approved Movie List 10-9-12

APPROVED NSH MOVIE SCREENING COMMITTEE R-RATED and NON-RATED MOVIE LIST Updated October 9, 2012 (Newly added films are in the shaded rows at the top of the list beginning on page 1.) Film Title ALEXANDER THE GREAT (1968) ANCHORMAN (2004) APACHES (also named APACHEN)(1973) BULLITT (1968) CABARET (1972) CARNAGE (2011) CINCINNATI KID, THE (1965) COPS CRUDE IMPACT (2006) DAVE CHAPPEL SHOW (2003–2006) DICK CAVETT SHOW (1968–1972) DUMB AND DUMBER (1994) EAST OF EDEN (1965) ELIZABETH (1998) ERIN BROCOVICH (2000) FISH CALLED WANDA (1988) GALACTICA 1980 GYPSY (1962) HIGH SCHOOL SPORTS FOCUS (1999-2007) HIP HOP AWARDS 2007 IN THE LOOP (2009) INSIDE DAISY CLOVER (1965) IRAQ FOR SALE: THE WAR PROFITEERS (2006) JEEVES & WOOSTER (British TV Series) JERRY SPRINGER SHOW (not Too Hot for TV) MAN WHO SHOT LIBERTY VALANCE, THE (1962) MATA HARI (1931) MILK (2008) NBA PLAYOFFS (ESPN)(2009) NIAGARA MOTEL (2006) ON THE ROAD WITH CHARLES KURALT PECKER (1998) PRODUCERS, THE (1968) QUIET MAN, THE (1952) REAL GHOST STORIES (Documentary) RICK STEVES TRAVEL SHOW (PBS) SEX AND THE SINGLE GIRL (1964) SITTING BULL (1954) SMALLEST SHOW ON EARTH, THE (1957) SPLENDER IN THE GRASS APPROVED NSH MOVIE SCREENING COMMITTEE R-RATED and NON-RATED MOVIE LIST Updated October 9, 2012 (Newly added films are in the shaded rows at the top of the list beginning on page 1.) Film Title TAMING OF THE SHREW (1967) TIME OF FAVOR (2000) TOLL BOOTH, THE (2004) TOMORROW SHOW w/ Tom Snyder TOP GEAR (BBC TV show) TOP GEAR (TV Series) UNCOVERED: THE WAR ON IRAQ (2004) VAMPIRE SECRETS (History -

SUSAN GERMAINE Hair Stylist IATSE 706

SUSAN GERMAINE Hair Stylist IATSE 706 FILM THE TWILIGHT SAGA: Department Head, Vancouver BREAKING DAWN PARTS 1 AND 2 Director: Bill Condon Cast: Robert Pattison, Taylor Lautner, Billy Burke YELLOW SUBMARINE Hair Designer Director: Robert Zemeckis THE NEXT THREE DAYS Personal Hair Stylist to Russell Crowe Director: Paul Haggis TRON: LEGACY Personal Hair Stylist to Jeff Bridges Director: Joseph Kosinski PUBLIC ENEMIES Personal Hair Stylist to Marion Cotillard Director: Michael Mann THE DAY THE EARTH STOOD STILL Personal Hair Stylist to Keanu Reeves Director: Scott Derrickson A CHRISTMAS CAROL Hair Designer Director: Robert Zemeckis STREET KINGS Department Head Personal Hair Stylist to Keanu Reeves Director: David Ayer Cast: Keanu Reeves, Hugh Laurie, Chris Evans, Forrest Whitaker 3:10 TO YUMA Personal Hair Stylist to Russell Crowe Director: James Mangold SLIPSTREAM Department Head Director: Anthony Hopkins Cast: Christian Slater, Gena Rowlands, Anthony Hopkins FRACTURE Department Head Director: Gregory Hoblit Cast: Anthony Hopkins, Embeth Davidtz, Ryan Gosling, Rosamund Pike THE MILTON AGENCY Susan Germaine 6715 Hollywood Blvd #206, Los Angeles, CA 90028 Hair Telephone: 323.466.4441 Facsimile: 323.460.4442 IATSE 706 [email protected] www.miltonagency.com Page 1 of 3 BEOWULF Hair Designer Director: Robert Zemeckis Cast: Robin Wright Penn, Anthony Hopkins, John Malkovich, Alison Lohman, Brendan Gleeson STICK IT Personal Hair Stylist to Jeff Bridges Director: Jessica Bendinger SKY HIGH Department Head Personal Hair Stylist to Kurt -

Extensions of Remarks E129 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

February 14, 2006 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E129 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS HONORING CHARLES C. COOK, SR. and is currently an adjunct faculty member at J. Jasen entered into his eternal rest on Feb- ON HIS RETIREMENT FROM THE Cleveland State University. ruary 4, 2006, at the age of 90. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE Her life long professional focus on improving Without seeking to be repetitive, Mr. Speak- the state of struggling urban school districts is er, the fact remains that Judge Jasen was HON. VERNON J. EHLERS evidenced throughout her profession. Her ca- widely regarded as one of the sharpest legal minds of his era. Taking his seat on the Court OF MICHIGAN reer in education began in her hometown of New York City, where she taught at the ele- of Appeals back in the days when that bench IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES mentary and high school levels. She later was still elected by popular vote statewide, Tuesday, February 14, 2006 served as a school principal and District Ad- Judge Jasen was the last western New Yorker Mr. EHLERS. Mr. Speaker, I rise to honor ministrator and served twice as Super- to serve on the court, and his decisions were Charles C. Cook, Sr., for his 36 years of ex- intendent of two of the lowest performing widely regarded as fair and impeccably re- emplary service at the U.S. Government Print- school districts in New York City, Chancellor’s searched. Rising to the position of senior as- ing Office, GPO. District and Crown Heights District in Brooklyn. sociate judge before his mandated retirement Charlie came to the GPO in November 1969 Her leadership is credited with dramatically im- in 1985, Judge Jasen was well known as a and was assigned as a Compositor in the proving academic achievement in both of lawyer’s judge—someone who knew the law, Monotype Section.