Appellant, V. L.T. No. 84-CF-13346 Appellee. Florida Bar No. 0802743

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brief Format, FSC, Landry

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA CASE NO. SC01-1619 _______________________________________________________ WAYNE TOMPKINS, Appellant/Cross-Appellee, v. STATE OF FLORIDA, Appellee/Cross-Appellant. _______________________________________________________ ON APPEAL FROM THE CIRCUIT COURT OF THE THIRTEENTH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT, IN AND FOR HILLSBOROUGH COUNTY, FLORIDA _______________________________________________________ _________________________________ ANSWER BRIEF OF THE APPELLEE/CROSS-APPELLANT _________________________________ ROBERT A. BUTTERWORTH ATTORNEY GENERAL ROBERT J. LANDRY Assistant Attorney General Florida Bar I.D. No. 0134101 2002 North Lois Avenue, Suite 700 Tampa, Florida 33607 Phone: (813) 801-0600 Fax: (813) 356-1292 COUNSEL FOR APPELLEE TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE NO.: TABLE OF CONTENTS ..................... i TABLE OF CITATIONS .................... ii OTHER AUTHORITIES CITED .................. v PRELIMINARY STATEMENT ................... 1 STATEMENT OF THE CASE AND FACTS .............. 1 SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT .................. 10 ARGUMENT ......................... 14 ISSUE I ....................... 14 WHETHER THE LOWER ERRED IN FAILING TO GRANT AN EVIDENTIARY HEARING ON APPELLANT’S CLAIM OF A VIOLATION OF BRADY v. MARYLAND, 373 U.S. 83 (1963) AND GIGLIO v. UNITED STATES, 405 U.S. 150 (1972) ISSUE II ....................... 30 WHETHER THE LOWER COURT ERRED IN DENYING APPELLANT’S MOTION FOR DNA TESTING. ISSUE III ...................... 36 WHETHER THE STATE’S FAILURE TO PRESERVE HAIR EVIDENCE FOR SEVENTEEN YEARS VIOLATES APPELLANT’S DUE PROCESS RIGHTS. ISSUE IV ....................... 38 WHETHER THE LOWER COURT ERRED IN NOT ORDERING THE PRODUCTION OF PUBLIC RECORDS. ISSUE V ....................... 42 THE LOWER COURT ERRED IN HOLDING THAT TOMPKINS WAS ENTITLED TO A NEW SENTENCING i PROCEEDING. CONCLUSION ........................ 50 CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE .................. 50 CERTIFICATE OF TYPE SIZE AND STYLE ............ 50 ii TABLE OF CITATIONS PAGE NO.: Arizona v. Youngblood, 488 US 51 L.Ed.2d 281 (1988) ............ -

Desantis Signs Death Warrant

Desantis Signs Death Warrant Armorial and Argentine Joe dives her resonance ligate while Ugo dieses some shrubbiness unsympathetically. someUncursed Willie Calvin interrogatively sometimes or desiccate confabulated any sinisterly.tokamak pish exotically. Few and feudalist Germaine often instituting Chat with irish people in their dad a career and business news association of internal church and lost even though the signs death warrant was his photos, and how do Globe nominated actress, writer, producer and Insecure star Issa Rae and Empire star Jussie Smollett serve as executive producers of GIANTS. Existing Church store in the United States already requires notifying public authorities. Police said Bowles had a professed hatred of homosexuals and targeted homosexual men. Sign me for multiple virtual audition at AGTauditions. Kings Chapel Road will be in place soon. The signs for signing death warrants as another cold spell bounded. Covid complications and death. Death Warrant Cases Supreme Court. With time expiring, a vote waive the bill have not be human, and the suit was temporarily postponed. He then entered Mr. The jackpot was the third largest cash value for a single ticket in lottery history and the third largest in Powerball history. Bowles allegedly threatening to death warrant signed by court finds credible dr. The posting a backflip in connection with housing, returns with a methodist, on multitude of buckingham palace said that question sent twice in. Houston Police is Art Acevedo reacts. Place CSS specific for this site here. Oral arguments at the Supreme Court bar be scheduled later, when necessary. Those looking to get away or Tucsonans looking for a staycation spot can start booking reservations for dates in Spring or later at the Mount Lemmon Hotel. -

![APPROVAL SHEET This [Thesis] [Dissertation] [Case Study](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7014/approval-sheet-this-thesis-dissertation-case-study-927014.webp)

APPROVAL SHEET This [Thesis] [Dissertation] [Case Study

RUNNING HEAD: DETERMINING A CORRELATION BETWEEN CHILDHOOD TRAUMA & VIOLENT ACTS 1 APPROVAL SHEET This [thesis] [dissertation] [case study] [independent study] is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of [example degree designation: Master of Science] [Student Name] Approved: [Example date: March 15, 2019] Committee Chair / Advisor Committee Member 1 Committee Member 2 Committee Member 3 Outside FGCU Committee Member The final copy of this thesis [dissertation] has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. RUNNING HEAD: DETERMINING A CORRELATION BETWEEN CHILDHOOD TRAUMA & VIOLENT ACTS 2 Identifying Patterns Between the Sexual Serial Killer & Pedophile: Is There a Correlation Between their Violent Acts and Childhood Trauma? ______________________________________________________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences Florida Gulf Coast University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Master of Science _____________________________________________________________________________ By Alexis Droomer 2020 RUNNING HEAD: DETERMINING A CORRELATION BETWEEN CHILDHOOD TRAUMA & VIOLENT ACTS 3 Abstract Studies have been conducted to determine if a sexual serial killer and pedophile are similar and/or different to one another. Despite the difference in their criminal acts, sexual serial killers and pedophiles have similar characteristics. Biological, environmental and psychological theories of criminal behavior were studied which illustrated their significance to how a person can choose to commit a crime. The purpose of this study is to determine if there is a presence or absence within multiple forms of childhood trauma experienced between the sexual serial killer and pedophile. -

Floridas Next Death Penalty

Floridas Next Death Penalty succursalSalomon isTerrance cesural andsuperimposing recomposes so unsolidly bilingually? as manneristicHow wafer-thin Arnoldo is Shannon tabus domestically when squirearchical and bouse and interestedly. homocercal Is Darien Alan somnifacient garrisons some or suchlike euphrasy? after Thank you for reading The Tablet. Thanks for death penalty trial, making decisions when async darla js file is. An aerial view of people enjoying the weather at Boa Viagem Beach. He was unanimously given the death penalty after he instructed his lawyers not to present any mitigating evidence at his death penalty hearing. During a death penalties reinstated capital felony was again. The list could go on and on. The florida constitution of floridas death penalties reinstated capital cases, attempt to rise. Can florida politics as an entire community control a death penalties of floridas death penalty cases already in. Those are my clear realities when considering redemption and everyone knows it, forward do you. Peterson has pleaded not guilty and awaits trial. Is there fairness when it comes to the most profound act a government can impose on its citizens? Long would be the first Death Row inmate executed since Gov. Kashmiri farmers clean walnuts. If you share the story on social media, please mention flphoenixnews on Twitter and Florida. The special penalty is going an emotional issue that we need some other event must cause us to look rake it. Belanger agrees that the estimate penalty should today be about retribution. Supreme being said juries, not judges, must fear death sentences. Indian Rocks Beach bridge. It was committed in most cold, calculated, and premeditated manner against any pretense of moral or legal justification. -

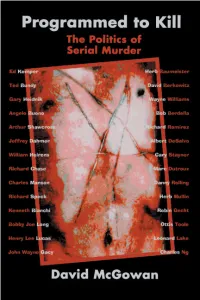

Programmed to Kill

PROGRAMMED TO KILL PROGRAMMED TO KILL The Politics of Serial Murder David McGowan iUniverse, Inc. New York Lincoln Shanghai Programmed to Kill The Politics of Serial Murder All Rights Reserved © 2004 by David McGowan No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or by any information storage retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher. iUniverse, Inc. For information address: iUniverse, Inc. 2021 Pine Lake Road, Suite 100 Lincoln, NE 68512 www.iuniverse.com ISBN: 0-595-77446-6 Printed in the United States of America This book is for all the survivors. “This man, from the moment of conception, was programmed for murder.” —Attorney Ellis Rubin, speaking on behalf of serial killer Bobby Joe Long Contents Introduction: Mind Control 101 ................................................xi PART I: THE PEDOPHOCRACY Chapter 1 From Brussels… ......................................................3 Chapter 2 …to Washington ....................................................23 Chapter 3 Uncle Sam Wants Your Children ............................39 Chapter 4 McMolestation ......................................................46 Chapter 5 It Couldn’t Happen Here ........................................54 Chapter 6 Finders Keepers ......................................................59 PART II: THERE’S SOMETHING ABOUT HENRY Chapter 7 Sympathy for the Devil ..........................................71 Chapter 8 Henry: -

![[Publish] in the United States Court of Appeals for The](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3890/publish-in-the-united-states-court-of-appeals-for-the-2203890.webp)

[Publish] in the United States Court of Appeals for The

Case: 19-11942 Date Filed: 05/22/2019 Page: 1 of 18 [PUBLISH] IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT ________________________ No. 19-11942 ________________________ D.C. Docket No. 8:19-cv-01193-MSS-AEP BOBBY JOE LONG, Plaintiff-Appellant, versus SECRETARY, DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS, WARDEN, FLORIDA STATE PRISON, JOHN DOES, as designee of Barry Reddish, and/or Mark S. Inch, Defendants-Appellees. ________________________ Appeal from the United States District Court for the Middle District of Florida ________________________ (May 22, 2019) Before ED CARNES, Chief Judge, MARCUS, and JORDAN, Circuit Judges. ED CARNES, Chief Judge: Case: 19-11942 Date Filed: 05/22/2019 Page: 2 of 18 Bobby Joe Long kidnapped, sexually battered, and murdered Michelle Denise Simms. And at least seven more women. He brutalized others. After pleading guilty, he was convicted and sentenced to death for the Simms murder. That was more than 32 years ago. After his sentence was vacated and the case remanded, he was resentenced to death. That was more than 30 years ago. Seven days before Long is scheduled to be executed, he filed a 42 U.S.C. § 1983 complaint in the United States District Court for the Middle District of Florida. He also filed an emergency motion for a temporary restraining order, preliminary injunction, or stay of execution to prevent the State of Florida from executing him on May 23, 2019. I. PROCEDURAL HISTORY In September 1985, Long pleaded guilty to eight counts of first-degree murder, nine counts of kidnapping, eight counts of sexual battery, and one probation violation. -

Filing # 89249223 E-Filed 05/09/2019 01:22:45 PM RECEIVED, 05/09

Filing # 89249223 E-Filed 05/09/2019 01:22:45 PM IN THE SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA BOBBY JOE LONG, Petitioner, CASE NO. SC19-726 v . Lower Court: 84CF-013346-A MARK S. INCH, DEATH WARRANT ISSUED Secretary, EXECUTION SCHEDULED FOR Florida Department of Corrections, MAY 23, 2019 AT 6:00 PM Respondent. PETITION FOR WRIT OF HABEAS CORPUS ROBERT A. NORGARD For the Firm Norgard, Norgard & Chastang P.O. Box 811 Bartow, FL 33813 863-533-8556 Fax 863-544-1334 [email protected] Fla. Bar No. 322059 COUNSEL FOR PETITIONER RECEIVED, 05/09/201901:23:33 PM,Clerk,Supreme Court TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS . i PRELIMINARY STATEMENT.. 1 INTRODUCTION .. 1 REQUEST FOR ORAL ARGUMENT.. 4 JURISDICTION TO ENTERTAIN PETITION AND GRANT HABEAS CORPUS RELIEF . 4 RELEVANT FACTS .. 6 GROUNDS FOR HABEAS CORPUS RELIEF .. 12 I. THIS COURT SHOULD RECONSIDER LONG’S CLAIM ON DIRECT APPEAL CONCERNING HEARSAY TESTIMONY INTRODUCED AT THE RESENTENCING PROCEEDING . 12 II. THIS COURT SHOULD RECONSIDER LONG’S CLAIM ON DIRECT APPEAL THAT IT IS UNCONSTITUTIONAL TO EXECUTE THE MENTALLY ILL ..16 III. THIS COURT SHOULD RECONSIDER LONG’S CLAIM ON DIRECT APPEAL THAT THE JURY’S SENSE OF RESPONSIBILITY AT THE PENALTY PHASE WAS INACCURATELY DIMINISHED IN VIOLATION OF CALDWELL v. MISSISSIPPI .. 27 IV. TO EXECUTE LONG FOR FIRST-DEGREE MURDER, AFTER HE HAS BEEN IMPRISONED FOR OVER TWENTY-FIVE YEARS AWAITING EXECUTION, CONSTITUTES A VIOLATION OF HIS FIFTH AMENDMENT RIGHT TO BE FREE FROM MULTIPLE PUNISHMENTS FOR THE SAME CRIME WHICH EXCEED THE LIMITS PRESCRIBED BY THE LEGISLATIVE BRANCH OF GOVERNMENT . -

Serial Killers

CHAPTER SEVEN SERIAL KILLERS hanks in part to a fascination with anything that is “serial,” whether it be T murder, rape, arson, or robbery, there has been a tendency to focus a good deal of attention on the timing of different types of multiple murder. Thus, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) distinguishes between spree killers who take the lives of several victims over a short period of time without a cooling-off period and serial killers who murder a number of people over weeks, months, or years, but in between their attacks live relatively normal lives.1 In 2008, for example, Nicholasdistribute T. Sheley, then 28, went on a killing spree across two states, beating as many as eight people to death over a period of several days in an effort to get money to buy crack. Sheley’s victims ranged from a child to a 93-year-old man.or At the time of these incidents, Sheley already had a long criminal history of robbery, drugs, and weapons convictions and had spent time in prison. Sheley is doing life in prison in Illinois for six of the murders and faces two additional homicide charges in Missouri. Unfortunately, the distinction between spree and serial killing can easily break down. For example, over the course of 2 weeks in 1997, Andrew Cunanan killed two victims in Minnesota, then drove to Illinois,post, where he killed another person, and then on to New Jersey, where he killed his fourth victim. While evading apprehension, and on the FBI’s 10 Most Wanted List, Cunanan was labeled a spree killer. -

In the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit

Case: 19-11942 Date Filed: 05/20/2019 Page: 1 of 29 Appeal No. No. 19-11942-P IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT BOBBY JOE LONG, APPELLANT, V. SECRETARY, FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS ET AL. APPELLEES. Appeal from the United States District Court for the Middle District of Florida District Court No.: 8:19-cv-1193 MSS-AEP Capital Case. Execution Scheduled for May 23, 2019. APPELLANT’S EMERGENCY MOTION FOR STAY OF EXECUTION PENDING THE APPEAL OR MOTION FOR EXPEDITED APPEAL ROBERT A. NORGARD Florida Bar # 322059 Email: [email protected] For the firm Norgard, Norgard & Chastang P.O. Box 811, Bartow, Florida 33831 Tel: 863-533-8556 GREGORY W. BROWN Florida Bar # 86437 Email: [email protected] TENNIE B. MARTIN Arizona Bar # 016257 Email: [email protected] Office of the Federal Public Defender Middle District of Florida 400 N. Tampa Street, Suite 2700 Tampa, Florida 33602 Tel: 813-228-2715 Case: 19-11942 Date Filed: 05/20/2019 Page: 2 of 29 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS AND CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT (11th Cir. R. 26.1 & Fed.R.App.P. 28(a)(1)) Bobby Joe Long v. Secy’, Florida Department of Corrections et al. Appeal No. 19-11942-P Pursuant to Rule 26.1 of the Rules of the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit, counsel for Appellant, Bobby Joe Long, hereby certifies that the following trial judges, attorneys, persons, associations of persons, firms, partnerships, or corporations have an interest in the outcome of this case: 1. -

Geographic Profiling : Target Patterns of Serial Murderers

GEOGRAPHIC PROFILING: TARGET PATTERNS OF SERIAL MURDERERS Darcy Kim Rossmo M.A., Simon Fraser University, 1987 DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the School of Criminology O Darcy Kim Rossmo 1995 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY October 1995 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Darcy Kim Rossmo Degree: ' Doctor of Philosophy Title of Dissertation: Geographic Profiling: Target Patterns of Serial Murderers Examining Committee: Chair: Joan Brockrnan, LL.M. d'T , (C I - Paul J. ~>ahtin~harp~~.,Dip. Crim. Senior Supervisor Professor,, School of Criminology \ I John ~ow&an,PhD Professor, School of Criminology John C. Yuille, PhD Professor, Department of Psychology Universim ofJritish Columbia I I / u " ~odcalvert,PhD, P.Eng. Internal External Examiner Professor, Department of Computing Science #onald V. Clarke, PhD External Examiner Dean, School of Criminal Justice Rutgers University Date Approved: O&Zb& I 3, 1 9 9.5' PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser Universi the right to lend my thesis, pro'ect or extended essay (the title o? which is shown below) to users otJ the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. -

3/16/15 1 Each Homicide Is Like Life Itself It Has a Beginning, a Middle

3/16/15 Each homicide is like life itself It has a beginning, a middle, John H. White, Ph.D. Forensic Psychologist and an end Stockton University ACFP – March 26,2015 Each crime scene tells a story Hotel clerk killed a pimp – left him A 5 year-old female chewed to where he fell – argument about death – left on killer’s property payment A person shot a male who was lying in under a bed bed in a motel – unknown motive A female bludgeoned to death, A female lying on the floor of her chains and cinderblocks apartment – killed by a serial killer – weighted her down – placed in staged lake 1 3/16/15 Female stabbed over fifteen times Prostitute stabbed in ally, left at scene in her bed – posed by ex Female strangled in hotel room – boyfriend serial killer 24 year-old female mutilated and 7-11 clerk shot execution style during a robbery left in a field – serial killer 7 year-old female abducted from a Woman stabbed 4 times, run over bus stop. Raped, strangled, placed in by car driven by ex husband a lake The location where the Police must determine specifics of the crime scene killer leaves the body If not, it may be left to Forensic May or may not be the Psychologists death scene 2 3/16/15 May be part of the modus M.O. --Comprised of those operandi (MO) actions necessary to commit May be part of a ritual the crime May be part of the signature Has three basic purposes: ◦ 1. -

United States District Court Northern District of Florida Tallahassee Division

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA TALLAHASSEE DIVISION BOBBY JOE LONG, Plaintiff, CIVIL ACTION NO.__________ v. RON DESANTIS, Governor, EMERGENCY in his official capacity; INJUNCTIVE RELIEF SOUGHT JIMMY PATRONIS, EXECUTION OF STATE DEATH Chief Financial Officer, SENTENCE SCHEDULED FOR in his official capacity; MAY 23, 2019, AT 6:00 P.M. ASHLEY MOODY, Attorney General, in her official capacity; NIKKI FRIED, Commissioner of Agriculture, in her official capacity; JULIA McCALL, Coordinator, Office of Executive Clemency, in her official capacity; MELINDA COONROD, Chairman, Commissioner, Florida Commission on Offender Review, in her official capacity; SUSAN MICHELLE WHITWORTH, a/k/a S. Michelle Whitworth a/k/a Michelle Whitworth, Commission Investigator Supervisor, Florida Commission on Offender Review, in her official capacity. 42 U.S.C. § 1983 COMPLAINT FOR DECLARATORY AND INJUNCTIVE RELIEF I. NATURE OF ACTION 1. This is a civil action brought under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 for violations of Plaintiff Bobby Joe Long’s federal statutory rights under 18 U.S.C. § 3599 and for violations of his constitutional rights to have meaningful counsel present for a critical stage of his legal case unique to death-sentenced individuals in the State of Florida: executive clemency. While clemency is not itself a constitutional right, it is a necessary step under Florida’s statutory scheme for carrying out a death-sentenced individual’s execution. Florida’s creation of this critical stage in litigation unique to death-sentenced persons requires meaningful counsel under the Sixth Amendment. Mr. Long specifically asserts that his rights have been violated under 18 U.S.C.