Feasibility Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annie Oakley Topic Guide for Chronicling America (

Annie Oakley Topic Guide for Chronicling America (http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov) Introduction Annie Oakley (1860-1926) was an American sharpshooter and exhibition shooter born in Darke County, Ohio, as Phoebe Ann Mosey. When she was five, her father died, and Annie learned to trap, shoot and hunt by age eight to help support her family. In 1875 (though some sources say it was in 1881), Annie met her future husband, Frank E. Butler, at the Baughman & Butler shooting act in Cincinnati, while beating him in a shooting contest. They were married a year later, and in 1885, they joined Buffalo Bill’s Wild West where she was given the nickname “Little Sure Shot.” Considered America’s first female star, Oakley traveled all over the United States and Europe showing off her skills. Oakley set shooting records into her sixties, and also did philanthropic work for women’s rights and other causes. In 1925, she died in Greenville, Ohio. Important Dates . August 13, 1860: Annie Oakley is born Phoebe Ann Mosey in Darke County, Ohio. November 1875: Oakley defeats Frank E. Butler in a shooting contest. The pair marries a year later. 1885: Oakley and Butler join Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. 1889: Oakley travels to France to perform in the Paris Exposition. 1901: Oakley is injured in a train accident but recovers and returns to show business. 1912-1917: Oakley and Butler retire temporarily and reside in Cambridge, Maryland. 1917: Oakley and Butler move to North Carolina and return to public life. 1922: Oakley and Butler are injured in a car accident, but Oakley performs again a year or so later. -

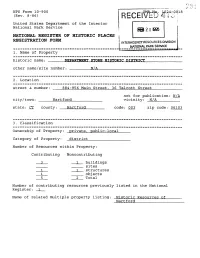

1 . Name of Property Other Name/Site

NPS Form 10-900 34-OQ18 (Rev. 8-86) RECE United States Department of the Interior National Park Service 2\ 1995 NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM JNTERAGENCY RESOURCES OMSION 1 . Name of Property historic name: ______ DEPARTMENT STORE HISTORIC DISTRICT ______________ other name/site number: _______N/A ______________________________ 2 . Location street & number: 884-956 Main Street. 36 Talcott Street __________ not for publication: N/A city/town: _____ Hartford __________ vicinity: N/A ________ state: CT county: Hartford______ code: 003 zip code: 06103 3 . Classification Ownership of Property: private, public-local ____ Category of Property: district_______________ Number of Resources within Property: Contributing Noncontributing 3 1 buildings ____ ____ sites 1 1 structures __ objects 2_ Total Number of contributing resources previously listed in the National Register: 1 Name of related multiple property listing: Historic Resources of Hartford USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form Page 2 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X meets does not meej: the National Register Criteria. ___ See cont. sheet. 2/15/95_______________ Date John W. Shannahan, Director Connecticut Historical Crmni ggj ran State or Federal agency and bureau In my opinion, the property ___ meets does not meet the National Register criteria. __ See continuation sheet. -

Selected Highlights of Women's History

Selected Highlights of Women’s History United States & Connecticut 1773 to 2015 The Permanent Commission on the Status of Women omen have made many contributions, large and Wsmall, to the history of our state and our nation. Although their accomplishments are too often left un- recorded, women deserve to take their rightful place in the annals of achievement in politics, science and inven- Our tion, medicine, the armed forces, the arts, athletics, and h philanthropy. 40t While this is by no means a complete history, this book attempts to remedy the obscurity to which too many Year women have been relegated. It presents highlights of Connecticut women’s achievements since 1773, and in- cludes entries from notable moments in women’s history nationally. With this edition, as the PCSW celebrates the 40th anniversary of its founding in 1973, we invite you to explore the many ways women have shaped, and continue to shape, our state. Edited and designed by Christine Palm, Communications Director This project was originally created under the direction of Barbara Potopowitz with assistance from Christa Allard. It was updated on the following dates by PCSW’s interns: January, 2003 by Melissa Griswold, Salem College February, 2004 by Nicole Graf, University of Connecticut February, 2005 by Sarah Hoyle, Trinity College November, 2005 by Elizabeth Silverio, St. Joseph’s College July, 2006 by Allison Bloom, Vassar College August, 2007 by Michelle Hodge, Smith College January, 2013 by Andrea Sanders, University of Connecticut Information contained in this book was culled from many sources, including (but not limited to): The Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame, the U.S. -

Women's History Is Everywhere: 10 Ideas for Celebrating in Communities

Women’s History is Everywhere: 10 Ideas for Celebrating In Communities A How-To Community Handbook Prepared by The President’s Commission on the Celebration of Women in American History “Just think of the ideas, the inventions, the social movements that have so dramatically altered our society. Now, many of those movements and ideas we can trace to our own founding, our founding documents: the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. And we can then follow those ideas as they move toward Seneca Falls, where 150 years ago, women struggled to articulate what their rights should be. From women’s struggle to gain the right to vote to gaining the access that we needed in the halls of academia, to pursuing the jobs and business opportunities we were qualified for, to competing on the field of sports, we have seen many breathtaking changes. Whether we know the names of the women who have done these acts because they stand in history, or we see them in the television or the newspaper coverage, we know that for everyone whose name we know there are countless women who are engaged every day in the ordinary, but remarkable, acts of citizenship.” —- Hillary Rodham Clinton, March 15, 1999 Women’s History is Everywhere: 10 Ideas for Celebrating In Communities A How-To Community Handbook prepared by the President’s Commission on the Celebration of Women in American History Commission Co-Chairs: Ann Lewis and Beth Newburger Commission Members: Dr. Johnnetta B. Cole, J. Michael Cook, Dr. Barbara Goldsmith, LaDonna Harris, Gloria Johnson, Dr. Elaine Kim, Dr. -

Women by County

WOMEN BY COUNTY Albany County Maria Van Rensselaer, 1645-1688 (Colonial and Revolutionary Eras) “Mother” Ann Lee, 1736-1784 (Faith Leaders) Harriet Myers, 1807-1865 (Abolition and Suffrage) Columbia County Margaret Beekman Livingston, 1724-1800 (Entrepreneurs) “Mother” Ann Lee, 1736-1784 (Faith Leaders) Elizabeth Freeman, “Mumbet,” 1742-1829 (Abolition and Suffrage) Janet Livingston Montgomery, 1743-1828 (Colonial & Revolutionary War Eras) Flavia Marinda Bristol, 1824-1918 (Entrepreneurs) Ida Helen Ogilvie, 1874-1963 (STEM) Edna St. Vincent Millay, 1892-1950 (The Arts) Ella Fitzgerald, 1917-1996 (The Arts) Lillian “Pete” Campbell, 1929-2017 (Reformers, Activists, and Trailblazers) Dutchess County Cathryna Rombout Brett, 1687-1763 (Entrepreneurs) Janet Livingston Montgomery, 1743-1828 (Colonial & Revolutionary War Eras) Sybil Ludington, 1761-1839 (Colonial & Revolutionary War Eras) Lucretia Mott, 1793-1880 (Abolition and Suffrage) Maria Mitchell, 1818-1889 (STEM) Antonia Maury, 1866-1952 (STEM) Beatrix Farrand, 1872-1959 (STEM) Eleanor Roosevelt, 1884-1962 (Reformers, Activists, and Trailblazers) Inez Milholland, 1886-1916 (Abolition and Suffrage) Edna St. Vincent Millay, 1892-1950 (The Arts) Dorothy Day, 1897-1980 (Faith Leaders) Elizabeth “Lee” Miller, 1907-1977 (Reformers, Activists, and Trailblazers) Jane Bolin, 1908-2007 (Reformers, Activists, and Trailblazers) Katharine Graham, 1917-2001(Entrepreneurs) Frances “Franny” Reese, 1917-2003 (Reformers, Activists, and Trailblazers) Raquel Rabinovich, b. 1929 (The Arts) Greene County Sybil Ludington, 1761-1839 (Colonial and Revolutionary War Eras) Candace Wheeler, 1827-1923 (The Arts) Margaret Newton Van Cott, 1830-1914 (Faith Leaders) Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman “Nellie Bly,” 1864-1922 (Reformers, Activists…) Ruth Franckling Reynolds, 1918-2007 (Reformers, Activists, and Trailblazers) Orange County Jane Colden, 1724-1760 (STEM) Margaret “Capt. -

238 Linear Feet Creator Annie Smith Peck

BROOKLYN COLLEGE LIBRARY ARCHIVES & SPECIAL COLLECTIONS 2900 BEDFORD AVENUE BROOKLYN NEW YORK 11210 718.951.5346 http://library.brooklyn.cuny.edu THE ANNIE SMITH PECK COLLECTION Accession #89-002 Dates Bulk dates: 1873-1935 Extent 16.5 cubic feet; 238 linear feet Creator Annie Smith Peck (1850-1935) Access / Use The Collection is open for research. Copyright is retained by Brooklyn College. Files can be accessed at the Brooklyn College Library Archives & Special Collection, 2900 Bedford Ave., Brooklyn, New York, Main floor (Room 130). 1 Languages English, German, Greek and Latin Finding aid Guide presently available in-house and on-line. Acquisition/Appraisal This collection was donated to Brooklyn College Archives by the late Prof. Shaista Rahman, Professor Emeritus of English, Brooklyn College. In 2016, additional correspondence was donated by Hannah Kimberley. Description Control: Guide adheres to that prescribed by Describing Archives: A Content Standard. Preferred Citation Item, folder title, box number, The Annie Smith Peck Collection, Brooklyn College Archives & Special Collections, Brooklyn College Library Subject Heading Peck, Annie S., 1850-1935. South America -- Economic conditions -- 1918-1961. South America -- Description and travel. Mountaineering. Peru -- Description and travel. Bolivia -- Description and travel. Huascaran Mountain (Peru). Related Materials New York Times newspaper 1908-1934 2 Biographical Note Annie Smith Peck (1850-1935), scholar and mountaineer, was born in Providence, R. I., October 19, 1850, the youngest of five children of George Batchelder Peck and Ann Power Smith Peck. Mr. Peck (father) was a graduate of Brown University and a member of the Providence City Council with a successful law practice. He also owned a wood and coal yard. -

The 19Th Amendment

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Women Making History: The 19th Amendment Women The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation. —19th Amendment to the United States Constitution In 1920, after decades of tireless activism by countless determined suffragists, American women were finally guaranteed the right to vote. The year 2020 marks the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. It was ratified by the states on August 18, 1920 and certified as an amendment to the US Constitution on August 26, 1920. Developed in partnership with the National Park Service, this publication weaves together multiple stories about the quest for women’s suffrage across the country, including those who opposed it, the role of allies and other civil rights movements, who was left behind, and how the battle differed in communities across the United States. Explore the complex history and pivotal moments that led to ratification of the 19th Amendment as well as the places where that history happened and its continued impact today. 0-31857-0 Cover Barcode-Arial.pdf 1 2/17/20 1:58 PM $14.95 ISBN 978-1-68184-267-7 51495 9 781681 842677 The National Park Service is a bureau within the Department Front cover: League of Women Voters poster, 1920. of the Interior. It preserves unimpaired the natural and Back cover: Mary B. Talbert, ca. 1901. cultural resources and values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this work future generations. -

Julia Anna Gardner Proceedings Volume of the Geological Society of America Annual Report for 1960 Pp

GEOL. soc. AM., PROC. FOR 1960 PLATE 6 JULIA ANNA GARDNER PROCEEDINGS VOLUME OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA ANNUAL REPORT FOR 1960 PP. 87-92. PL. 6 FEBRUARY 1962 MEMORIAL TO JULIA ANNA GARDNER (1882-1960) By HARRY S. LADD Julia Anna Gardner, distinguished paleontol worked at the Museum under contract with the ogist and authority on the stratigraphy of the U. S. Geological Survey until, at the end of Coastal Plain, died at her home in Bethesda, 1917, she joined the Red Cross for duty in Maryland, on November 15, 1960, after a long France. After the war, early in 1920, she became illness. She was 78 years of age. a Paleontologist with the Survey, a position Julia Gardner was born in Chamberlain, she was to hold for the next 32 years. South Dakota, on January 26, 1882. Her father, Miss Gardner's doctor's thesis at Johns Dr. Charles Henry Gardner, a practicing Hopkins dealt with a part of the fauna of the physician in Chamberlain, died when Julia Upper Tertiary beds of Virginia and North was but four months old. Julia was raised by Carolina, but this document was not completed her mother, Julia Brackett Gardner. Much of and published until many years later. While Julia Anna's girlhood was spent in South with the Maryland Survey she studied Upper Dakota where her early schooling was by Cretaceous mollusks and some minor groups. Her comprehensive reports in the two volumes private tutors. In 1898 mother and daughter that appeared in 1916 constituted a valuable moved to North Adams, Massachusetts, where pioneering effort. -

SSAWW-2021-Conference-Program-11-July-2021.Docx

2021 SSAWW Conference Schedule (Draft 11 July 2021) WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 3 Conference Registration: 4:00-8:00 p.m., Regency THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 4 Registration: 6:30 a.m.-4:00 p.m., Regency Book exhibition: 8:15 a.m.-5:00 p.m., Brightons Mentoring Breakfast: 7:00 a.m.-8:15 a.m., Hamptons Thursday, 8:30-9:45 a.m. Session 1A, North Whitehall “Gothic Ecologies: Alcott, Her Contexts, and Contemporaries” Sponsored by the Louisa May Alcott Society Chair: Sandra Harbert Petrulionis, Pennsylvania State University, Altoona ● "Never Mind the Boys": Gothic Persuasions of Jane Goodwin Austin and Louisa May Alcott Kari Miller, Perimeter College at Georgia State University ● Wealth, Handicaps, and Jewels: Alcott's Gothic Tales of Dis-Possession Monika Elbert, Montclair State University ● Alcott in the Cadre of Scribbling Women: 'Realizing' the Female Gothic for Nineteenth Century American Periodicals Wendy Fall, Marquette University Session 1B, Guilford “Pedagogy and the Archives (Part I)” Chair: TBD ● Commonplace Book Practices and the Digital Archive Kirsten Paine, University of Pittsburgh ● Making Literary Artifacts and Exhibits as Acts of Scholarship Mollie Barnes, University of South Carolina Beaufort ● "My dearest sweet Anna": Transcribing Laura Curtis Bullard's Love Letters to Anna Dickinson and Zooming to the Library of Congress Denise Kohn, Baldwin Wallace University ● Nineteenth Century Science of Surgery as Cure for the Greatest Curse Sigrid Schönfelder, Universität Passau 1 - DRAFT: 11 July 2021 Session 1C, Westminster (Need AV) “Recovering Abolitionist Lives and Histories” Chair: Laura L. Mielke, University of Kansas ● Audubon's Black Sisters Brigitte Fielder, University of Wisconsin-Madison ● Recovery Work and the Case of Fanny Kemble's Journal of a Residence on a Georgia Plantation, 1838-39 Laura L. -

Our Kind of People: Social Status and Class Awareness in Post -Reconstruction African American Fiction

OUR KIND OF PEOPLE: SOCIAL STATUS AND CLASS AWARENESS IN POST -RECONSTRUCTION AFRICAN AMERICAN FICTION Andreá N. Williams A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English Chapel Hill 2006 Approved by Advisor: William L. Andrews Reader: James W. Coleman Reader: Philip F. Gura Reader: Trudier Harris Reader: Jane F. Thrailkill © 2006 Andreá N. Williams ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT ANDREÁ N. WILLIAMS: Our Kind of People: Social Status and Class Awareness in Post -Reconstruction African American Fiction (Under the dir ection of William L. Andrews) Postbellum African American fiction provides an index to the complex attitudes toward social status and class divisions that arose within post -Civil War black communities. As I argue, African American narratives in the last quarter of the nineteenth century encode the discourse of class in discussions of respectability, labor, and discrimination. Conceiving of class as a concept that does not necessarily denote economic conditions, both well -known and largely ignored narrativ es of the period emphasize moral and ideological parameters for judging social distinctions. Writers theorize whether intraracial class stratification thwarts black sociopolitical advancement, fracturing black communities from within, or conversely, foster s racial uplift led by the black “better class.” Though the fiction variably delineates social classes, each of the texts under study in Our Kind of People imagines classification as an inevitable and useful means of reforming the turn -of-the-century Ameri can social order. Subverting the class disparity spurred by Gilded Age materialism, Frances E. -

Fall 2013 Fall 2013

W ORCESTER W OMEN’S H ISTORY P ROJECT We remember our past . to better shape our future. WWHP VOL.WWHP 13, VOLUME NO. 2 13, NO. 2 FALL 2013 FALL 2013 WWHP and the Intergenerational Urban Institute at NOTICE Worcester State University are pleased to OF present 18th ANNUAL MEETING Michèle LaRue Thursday, October 24, 2013 in 5:30 p.m. Someone Must Wash the Dishes: Worcester Historical Museum followed by a talk by An Anti-Suffrage Satire Karen Board Moran Many women fought against getting the vote in the early 1900s, on her new book but none with more charm, prettier clothes—and less logic— than the fictional speaker in this satiric monologue written by Gates Along My Path pro-suffragist Marie Jenney Howe, back in 1912. “Woman suf- Booksigning frage is the reform against nature,” declares Howe’s unlikely, but irresistibly likeable, heroine. Light Refreshments “Ladies, get what you want. Pound pillows. Make a scene. Photo by Ken Smith of Quiet Heart Images Make home a hell on earth—but do it in a womanly way! That is All Welcome so much more dignified and refined than walking up to a ballot box and dropping in a piece of paper!” See page 3 for details. Reviewers have called this production “wicked” in its wit, and have labeled Michèle LaRue’s performance "side-splitting." An Illinois native, now based in New York, LaRue is a professional actress who tours nationally with a repertoire of shows by turn-of-the- previous-century American writers. Panel Discussion follows on the unfinished business of women’s rights. -

Search Titles and Presenters at Past AAHN Conferences from 1984

American Association for the History of Nursing, Inc. 10200 W. 44th Avenue, Suite 304 Wheat Ridge, CO 80033 Phone: (303) 422-2685 Fax: (303) 422-8894 [email protected] www.aahn.org Titles and Presenters at Past AAHN Conferences 1984 – 2010 Papers remain the intellectual property of the researchers and are not available through the AAHN. 2010 Co-sponsor: Royal Holloway, University of London, England September 14 - 16, 2010 London, England Photo Album Conference Podcasts The following podcasts are available for download by right-clicking on the talk required and selecting "Save target/link as ..." Fiona Ross: Conference Welcome [28Mb-28m31s] Mark Bostridge: A Florence Nightingale for the 21st Century [51Mb-53m29s] Lynn McDonald: The Nightingale system of training and its influence worldwide [13Mb-13m34s] Carol Helmstadter: Nightingale Training in Context [15Mb-16m42s] Judith Godden: The Power of the Ideal: How the Nightingale System shaped modern nursing [17Mb-18m14s] Barbra Mann-Wall: Nuns, Nightingale and Nursing [15Mb-15m36s] Dr Afaf Meleis: Nursing Connections Past and Present: A Global Perspective [58Mb-61m00s] 2009 Co-sponsor: School of Nursing, University of Minnesota September 24 - 27, 2009 Minneapolis, Minnesota Paper Presentations Protecting and Healing the Physical Wound: Control of Wound Infection in the First World War Christine Hallett ―A Silent but Serious Struggle Against the Sisters‖: Working-Class German Men in Nursing, 1903- 1934 Aeleah Soine, PhDc The Ties that Bind: Tale of Urban Health Work in Philadelphia‘s Black Belt, 1912-1922 J. Margo Brooks Carthon, PhD, RN, APN-BC The Cow Question: Solving the TB Problem in Chicago, 1903-1920 Wendy Burgess, PhD, RN ―Pioneers In Preventative Health‖: The Work of The Chicago Mts.