Interview Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interview Transcript

ORAL HISTORY 7 TRANSCRIPT GLYNN S. LUNNEY INTERVIEWED BY CAROL BUTLER HOUSTON, TX – 18 OCTOBER 1999 BUTLER: Today is October 18, 1999. This oral history with Glynn Lunney is being conducted in the offices of the Signal Corporation in Houston, Texas, for the Johnson Space Center Oral History Project. Carol Butler is the interviewer and is assisted by Kevin Rusnak and Jason Abbey. Thank you for joining us today, again. LUNNEY: You're welcome. Glad to be here. BUTLER: We began talking the last time about Apollo-Soyuz [Test Project (ASTP)], and you told us a little bit about how you got involved with it and how Chris [Christopher C.] Kraft [Jr.] had called you up and asked you to become a part of this program, and how that was a little bit of a surprise, but you jumped into it. What did you think about working with the Soviet Union and people that had for so long been considered enemies, who you'd been in competition with on the space program, but were also enemies of the nation, to say? LUNNEY: Especially on the front end, it's a fairly foreboding and intimidating kind of an idea. Of course, I was raised and came of age in the fifties and sixties, and we went through a great deal of scare with respect to the Soviet Union. The newsreels had the marches through Red Square, you know, with the missiles and so on, tanks. A lot of things happened to reinforce that. There was, of course, the Cuban Missile Crisis early in [President] John [F.] Kennedy's administration. -

Apollo Soyuz Test Project

https://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=20190025708 2019-08-31T11:45:11+00:00Z Karol J. Bobko Background • Soviet –American cooperation in space had been discussed as early as 1962 by NASA’s Hugh Dryden and Academician Blagonrovov. • The major objectives for a cooperative space mission were: – 1) Demonstration in space of the new androgynous docking system, and – 2) Improvement of communication and reduction of Cold War tensions between East and West • In October 1970 R. Gilruth headed a small NASA delegation for a visit to Moscow to promote space cooperation. That visit was successful. • Following additional meetings, when President Nixon visited Moscow in May 1972, he and Alexei Kosygin signed an agreement providing for cooperation and the peaceful uses of space – The leaders specifically approved the Apollo-Soyuz flight being planned and they agreed on a 1975 launch. • Dr. Glynn Lunney was appointed as the U.S. technical director of the project • The US crew was announced in January; the USSR crew in May of 1973 • The first training visit was cosmonauts visiting JSC in July of 1973 System Changes • A Docking Module was developed to: – Act as an airlock between the two spacecraft • The Apollo operated with a 100% oxygen but at .34 atmospheres • The Soyuz normally operated at 1.0 atmospheres but for this flight it operated at .68 atmospheres • Since the difference between the modules was only .34 atmospheres it was felt the danger of going from one pressure to the other, without pre-breathe, was minimal. – The Docking Module had extra oxygen and nitrogen and executed the change in pressures to allow passage back and forth between the modules – The docking module had no capability to remove CO2 Docking Module (Cont.) • The front end of the Docking Module had the APDS, which was used to dock with the Soyuz • The rear part of the Docking Module had the probe and drogue system which was used to dock with the Apollo Command Module. -

Apollo 13 Mission Review

APOLLO 13 MISSION REVIEW HEAR& BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON AERONAUTICAL AND SPACE SCIENCES UNITED STATES SENATE NINETY-FIRST CONGRESS SECOR’D SESSION JUR’E 30, 1970 Printed for the use of the Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 47476 0 WASHINGTON : 1970 COMMITTEE ON AEROKAUTICAL AND SPACE SCIENCES CLINTON P. ANDERSON, New Mexico, Chairman RICHARD B. RUSSELL, Georgia MARGARET CHASE SMITH, Maine WARREN G. MAGNUSON, Washington CARL T. CURTIS, Nebraska STUART SYMINGTON, bfissouri MARK 0. HATFIELD, Oregon JOHN STENNIS, Mississippi BARRY GOLDWATER, Arizona STEPHEN M.YOUNG, Ohio WILLIAM B. SAXBE, Ohio THOJfAS J. DODD, Connecticut RALPH T. SMITH, Illinois HOWARD W. CANNON, Nevada SPESSARD L. HOLLAND, Florida J4MES J. GEHRIG,Stad Director EVERARDH. SMITH, Jr., Professional staffMember Dr. GLENP. WILSOS,Professional #tad Member CRAIGVOORHEES, Professional Staff Nember WILLIAMPARKER, Professional Staff Member SAMBOUCHARD, Assistant Chief Clerk DONALDH. BRESNAS,Research Assistant (11) CONTENTS Tuesday, June 30, 1970 : Page Opening statement by the chairman, Senator Clinton P. Anderson-__- 1 Review Board Findings, Determinations and Recommendations-----_ 2 Testimony of- Dr. Thomas 0. Paine, Administrator of NASA, accompanied by Edgar M. Cortright, Director, Langley Research Center and Chairman of the dpollo 13 Review Board ; Dr. Charles D. Har- rington, Chairman, Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel ; Dr. Dale D. Myers, Associate Administrator for Manned Space Flight, and Dr. Rocco A. Petrone, hpollo Director -___________ 21, 30 Edgar 11. Cortright, Chairman, hpollo 13 Review Board-------- 21,27 Dr. Dale D. Mvers. Associate Administrator for Manned SDace 68 69 105 109 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIOSS 1. Internal coinponents of oxygen tank So. 2 ---_____-_________________ 22 2. -

Wings in Orbit Scientific and Engineering Legacies of the Space Shuttle

https://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=20100041317 2019-08-30T13:21:15+00:00Z National Aeronautics and Space Administration Wings In Orbit Scientific and Engineering Legacies of the Space Shuttle N. Wayne Hale Helen Lane Executive Editor Chief Editor Kamlesh Lulla Gail Chapline Editor Editor An agency-wide Space Shuttle book project involving contributions from all NASA centers Space Shuttle book: September 2010 Wings In Orbit A new, authentic and authoritative book written by the people of the Space Shuttle Program • Description of the Shuttle and its operations • Engineering innovations • Major scientific discoveries • Social, cultural, and educational legacies • Commercial developments • The Shuttle continuum, role of human spaceflight Vision Overall vision for the book: The “so what” factor? Our vision is to “inform” the American people about the accomplishments of the Space Shuttle and to “empower” them with the knowledge about the longest-operating human spaceflight program and make them feel “proud” about nation’s investment in science and technology that led to Space Shuttle Program accomplishments. Vision (continued) Focus: • Science and Engineering accomplishments (not history or hardware or mission activities or crew activities) • Audience: American public with interest in science and technology (e.g., Scientific American Readership: a chemical engineer, a science teacher, a physician, etc.) Definition of Accomplishment: • Space Shuttle Program accomplishments are those “technical results, developments, and innovations that will shape future space programs” or “have affected the direction of science or engineering” with a focus on unique contributions from the shuttle as a platform. Guiding Principles: • Honest • Technically correct • Capture the passion of the NASA team that worked on the program Editorial Board “…to review and provide recommendations to the Executive Editor on the contents and the final manuscript…” Wayne Hale, Chair of Board Iwan Alexander Steven A. -

Skylab: the Human Side of a Scientific Mission

SKYLAB: THE HUMAN SIDE OF A SCIENTIFIC MISSION Michael P. Johnson, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: J. Todd Moye, Major Professor Alfred F. Hurley, Committee Member Adrian Lewis, Committee Member and Chair of the Department of History Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Johnson, Michael P. Skylab: The Human Side of a Scientific Mission. Master of Arts (History), May 2007, 115pp., 3 tables, references, 104 titles. This work attempts to focus on the human side of Skylab, America’s first space station, from 1973 to 1974. The thesis begins by showing some context for Skylab, especially in light of the Cold War and the “space race” between the United States and the Soviet Union. The development of the station, as well as the astronaut selection process, are traced from the beginnings of NASA. The focus then shifts to changes in NASA from the Apollo missions to Skylab, as well as training, before highlighting the three missions to the station. The work then attempts to show the significance of Skylab by focusing on the myriad of lessons that can be learned from it and applied to future programs. Copyright 2007 by Michael P. Johnson ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not be possible without the help of numerous people. I would like to begin, as always, by thanking my parents. You are a continuous source of help and guidance, and you have never doubted me. Of course I have to thank my brothers and sisters. -

International Space Medicine Summit 2019

INTERNATIONAL SPACE MEDICINE SUMMIT 2019 October 10–13, 2019 • Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy • Houston, Texas INTERNATIONAL SPACE MEDICINE SUMMIT 2019 October 10–13, 2019 • Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy • Houston, Texas About the Event As we continue human space exploration, much more research is needed to prevent and/or mitigate the medical, psychological and biomedical challenges spacefarers face. The International Space Station provides an excellent laboratory in which to conduct such research. It is essential that the station be used to its fullest potential via cooperative studies and the sharing of equipment and instruments between the international partners. The application of the lessons learned from long-duration human spaceflight and analog research environments will not only lead to advances in technology and greater knowledge to protect future space travelers, but will also enhance life on Earth. The 13th annual International Space Medicine Summit on Oct. 10-13, 2019, brings together the leading physicians, space biomedical scientists, engineers, astronauts, cosmonauts and educators from the world’s spacefaring nations for high-level discussions to identify necessary space medicine research goals as well as ways to further enhance international cooperation and collaborative research. All ISS partners are represented at the summit. The summit is co-sponsored by the Baker Institute Space Policy Program, Texas A&M University College of Engineering and Baylor College of Medicine. Organizers Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy The mission of Rice University’s Baker Institute is to help bridge the gap between the theory and practice of public policy by drawing together experts from academia, government, media, business and nongovernmental organizations. -

The Elmer A. Sperry Award 2008

Eng-Russian-Sperry-Broc-COLOR-apr09:new-Apr2009 4/27/09 2:50 PM Page 1 The Elmer A. Sperry Award 2008 FOR ADVANCING THE ART OF TRANSPORTATION Eng-Russian-Sperry-Broc-COLOR-apr09:new-Apr2009 4/27/09 2:50 PM Page 3 Hаграда имени Элмера А. Сперри 2008 ЗА ПЕРЕДОВЫЕ ДОСТИЖЕНИЯ В ТРАНСПОРТЕ Eng-Russian-Sperry-Broc-COLOR-apr09:new-Apr2009 4/27/09 2:50 PM Page 4 The Elmer A. Sperry Award The Elmer A. Sperry Award shall be given in recognition of a distinguished engineering contribution which, through application, proved in actual service, has advanced the art of transportation whether by land, sea, air, or space. In the words of Edmondo Quattrocchi, sculptor of the Elmer A. Sperry Medal: “This Sperry medal symbolizes the struggle of man’s mind against the forces of nature. The horse represents the primitive state of uncontrolled power. This, as suggested by the clouds and celestial fragments, is essentially the same in all the elements. The Gyroscope, superimposed on these, represents the bringing of this power under control for man’s purposes.” Eng-Russian-Sperry-Broc-COLOR-apr09:new-Apr2009 4/27/09 2:50 PM Page 5 Presentation of The Elmer A. Sperry Award for 2008 to THOMAS P. STAFFORD GLYNN S. LUNNEY ALEKSEI A. LEONOV KONSTANTIN D. BUSHUYEV as leaders of the Apollo-Soyuz mission and as representatives of the Apollo-Soyuz docking interface design team: in recognition of seminal work on spacecraft docking technology and international docking interface methodology. By The Elmer A. Sperry Board of Award under the sponsorship of the: American Society of Mechanical Engineers American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers SAE International Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers American Society of Civil Engineers with special thanks to: The Boeing Company American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics at the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics Gala Washington, DC 13 May 2009 Eng-Russian-Sperry-Broc-COLOR-apr09:new-Apr2009 4/27/09 2:50 PM Page 2 General Thomas P. -

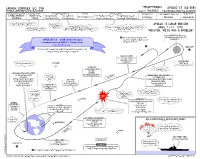

View the Apollo 13 Chart

APOLLO 13 (AS-508) LC-39A JULY 2015 JOHN F. KENNEDY SPACE CENTER AS-508-2 3rd LUNAR LANDING MISSION MISSION FACTS & HIGHLIGHTS Apollo 13 was to be NASA’s third mission to land on the Moon. The spacecraft launched from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Midway to the moon, an explosion in one of the oxygen tanks of the service module crippled the spacecraft. After the in-flight emergency, for safety reasons, the crew was forced to temporarily power down and evacuate the command module, taking refuge in the lunar module. The spacecraft then orbited the Moon without landing. Later in the flight, heading back toward Earth, the crew returned to the command module, restored power, jettisoned the damaged service module, then the lunar module and, after an anxious re- entry blackout period, returned safely to the Earth. The command module and its crew slasheddown in the South Pacific Ocean and were recovered by the U.S.S. Iwo Jima (LPH-2). FACTS • Apollo XIII Mission Motto: Ex Luna, Scientia • Lunar Module: Aquarius • Command and Service Module: Odyssey • Crew: • James A. Lovell, Jr. - Commander • John L. Swigert, Jr. - Command Module Pilot ( * ) • Fred W. Haise, Jr. - Lunar Module Pilot • NASA Flight Directors • Milt Windler - Flight Director Shift #1 • Gerald Griffin - Flight Director Shift #2 • Gene Kranz - Flight Director Shift #3 • Glynn Lunney - Flight Director Shift #4 • William Reeves - Systems • Launch Site: John F. Kennedy Space Center, Florida • Launch Complex: Pad 39A • Launch: 2:13 pm EST, April 11, 1970 •Orbit: • Altitude: 118.99 miles • Inclination 32.547 degrees • Earth orbits: 1.5 • Lunar Landing Site: Intended to be Fra Mauro (later became landing site for Apollo 14) • Return to Earth: April 17, 1970 • Splashdown: 18:07:41 UTC (1:07:41 pm EST) • Recovery site location: South Pacific Ocean (near Samoa) S21 38.6 W165 21.7 • Recovery ship: U.S.S. -

Interview Transcript

ORAL HISTORY 3 TRANSCRIPT GLYNN S. LUNNEY INTERVIEWED BY CAROL L. BUTLER HOUSTON, TEXAS – 8 FEBRUARY 1999 BUTLER: Today is February 8, 1999. This oral history is with Glynn Lunney at the offices of the Signal Corporation in Houston, Texas. The interview is being conducted for the Johnson Space Center Oral History Project by Carol Butler, assisted by Summer Chick Bergen and Kevin Rusnak. Thank you for joining us again. LUNNEY: You're welcome. Glad to be here. BUTLER: We'll start with Apollo. In the earlier interview you talked some about the early Apollo missions, Apollo 1, Apollo 7, and Apollo 8, but you mentioned in our last interview that while Gemini was going on, you were working on some of the unmanned Apollo missions. What can you tell us about what you did? LUNNEY: There were actually sort of two series of unmanned flights. One was called the boilerplate. "BP" was the designator, and it was a set of tests of the escape system, the Apollo abort escape system, the little tower that was on top of the spacecraft that would pull it over, pull it off the vehicle, if there were a problem during the launch phase. That was considered critical enough that there was a whole set of tests designed that were conducted out at White Sands. We used a solid rocket motor, and the idea was to boost the spacecraft to high dynamic pressures, high loads, and then trigger the abort system to see that it worked properly under a variety of sets of conditions. -

Spm July 2016

July 2016 Vol. 3 No. 7 National Aeronautics and Space Administration KENNEDY SPACE CENTER’S magazine FIRED UP! SLS booster passes major milestone Earth Solar Aeronautics Mars Technology Right ISS System & NASA’S Research Now Beyond LAUNCH National Aeronautics and Space Administration KENNEDY SPACE CENTER’S SCHEDULE Date: July 6, 9:36 p.m. EDT SPACEPORT MAGAZINE Mission: Launch of Expedition 48 Crew Description: Launch of the CONTENTS Expedition 48 crew on the Soyuz MS-01 spacecraft from 9 �������������������CCP Launch Site Integrator Misty Snopkowski the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan to the International 11 ����������������Final Spacecraft 1 major component arrives for assembly Space Station. http://go.nasa.gov/1VHuSAv 13 ����������������Juno spacecraft sets sights on orbit Date: July 18. 12:45 a.m. EDT 20 ����������������2016 advances mark Commercial Crew’s path to flight Mission: SpaceX CRS-9 Launch Description: An uncrewed SpaceX 22 ����������������Commercial Crew manufacturing gains momentum Dragon spacecraft, carrying crew GLENN CHIN supplies and station hardware, will 25 ����������������Astronauts provide vital feedback for CCP spacecraft lift off on a Falcon 9 rocket from I am the deputy manager for the Orion Production Opera- Space Launch Complex 40 at Cape tions Office within the Orion Program. Orion Production ����������������Kennedy Space Center makes land available 29 Canaveral Air Force Station. Operations is responsible for overseeing the production of the 32 ����������������Platforms provide access to world’s most powerful rocket http://go.nasa.gov/293FmfN Orion spacecraft for the Exploration Mission 1 launching in 2018. My Kennedy career started in 1989 with the histori- Targeted Date: August 34 ����������������NASA’s Ground Systems Team Puts Students ‘FIRST’ cal Spacelab Program as a “hands-on” fluid systems engineer. -

NASA's Glynn Lunney Author Robert H. Sholly, Col

February 2015 In This Issue Friendswood Library hosts authors... Election filing window Tree Giveaway helps NASA's Glynn Lunney Keep Friendswood Beautiful Highways Into Space: A first-hand 2015: The Year of the account of the beginnings of the Business human space program Weather watcher training Thursday, February 12 at 7 p.m. Friendswood Library events Lunney was a Medal of Freedom award Grill safety winner as part of the Mission Operations Team for Apollo 13. A book signing will conclude the event. Author Robert H. Sholly, Col., USA (Ret.) Young Soldiers Amazing Warriors: Inside one of the most highly decorated Mayor battalions of Vietnam Kevin M. Holland Thursday, February 26 at 7 p.m. Mayor Pro Tem Jim Hill Sholly is a multi-award winning author and businessman. He served two tours Council Position 1 in Vietnam, the first of which is Steve Rockey captured in his book. He began writing Young Soldiers Amazing Warriors after retiring from military and Council Position 2 corporate life. Sholly is currently the President of the 8th Billy Enochs Infantry Regiment Association. Council Position 4 Patrick J. McGinnis Election filing window Council Position 5 John Scott A General Election is scheduled to be held on May 9 to elect a Mayor, Council Position No. 1, and Council Position 6 Council Position No. 3. Carl Gustafson A packet with information for potential candidates is available and may be picked up in the City Secretary's office during regular office hours. City of Friendswood Mission Statement The period for a candidate to file an application for a place It is the Mission of on the ballot ends February 27, 2015, at 5 p.m. -

Interview Transcript

ORAL HISTORY 6 TRANSCRIPT GLYNN S. LUNNEY INTERVIEWED BY ROY NEAL HOUSTON, TEXAS – 26 APRIL 1999 NEAL: And I’m going to give you a little voice slate right at the top. This is Roy Neal. We’re speaking from the third floor of the old Mission Control, Building 30 at the Johnson Space Center [Houston, Texas]. Our guest is Glynn Lunney, G-l-y-n-n L-u-n-n-e-y. And if I misspelled it, he’d wince; so I know that that was the correct spelling. LUNNEY: That’s right. NEAL: And we are literally sitting just a few feet away from a place where you once wrote a lot of history, Glynn. So, let’s dive into that history if we can. As we ended our first interview, you had just discussed Apollo 13 in quite some detail. So, now we’d like to start by going into the other Apollo missions, and then we’ll move on to Apollo-Soyuz [Test- Project (ASTP)] and Skylab, if you want to. Or we can go into Space Station. But we’ll get to those things one small step at a time. So, let’s begin with the other Apollo missions. [Apollo] 7 was the first manned flight, and it came after the Apollo 1 [AS-204] fire. Was there any warning that Apollo, before that fire, perhaps was an accident waiting to happen? Did anybody really catch up to the facts of life in the program? LUNNEY: Well, there’s sort of two backgrounds for your question.