Nikolai Astrup in Dulwich

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oluf Wold Tornes Malerier Sett I Relasjon Til Symbolismen På 1890-Tallet Og I Overgangen Til Den Dekorative Retning I Norsk Kunst Etter 1900

Oluf Wold Tornes malerier sett i relasjon til symbolismen på 1890-tallet og i overgangen til den dekorative retning i norsk kunst etter 1900 Kristine Goderstad Masteroppgave i kunsthistorie 120 poeng Veileder Professor Øyvind Storm Bjerke Institutt for filosofi, idè- og kunsthistorie og klassiske språk Humanistisk fakultet Vår 2020 I II Oluf Wold Tornes malerier sett i relasjon til symbolismen på 1890-tallet og i overgangen til den dekorative retning i norsk kunst etter 1900 Masteroppgave i kunsthistorie Kristine Goderstad III © Kristine Goderstad 2020 Oluf Wold Tornes malerier sett i relasjon til symbolismen på 1890- tallet og i overgangen til den dekorative retning i norsk kunst etter 1900 Kristine Goderstad https://www.duo.uio.no/ Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo Forord IV Jeg vil gjerne få takke alle som har hjulpet meg underveis for hjelp og støtte under arbeidet med masteroppgaven: -Professor i kunsthistorie Øyvind Storm Bjerke for god veiledning og nyttige innspill under arbeidet. -Professor i kunsthistorie Marit Werenskiold som opprinnelig gav meg interessen og inspirasjonen til å lese og skrive om Oluf Wold Torne og kunstnere i hans samtid. -Cecilia Wahl, Oluf Wold Tornes barnebarn som velvillig har gitt meg innsyn i korrespondanse og sin private kunstsamling. -Turid Delerud, daglig leder ved Holmsbu Billedgalleri for all inspirasjon og hjelp. -Jeg må også få takke mine medstudenter Reidun Mæland og Cecilie Haugstøl Dubois som har vært til gjensidig støtte og inspirasjon gjennom hele studietiden. -En stor takk vil jeg også gi til mine venner som har støttet meg, og spesielt May Elin Flovik som har hjulpet til med korrigeringer og inspirerende innspill rundt oppgaven. -

Årets Kunstner 2016.2017.Pdf

Et barn er laget av hundre. Barnet har hundre språk hundre hender hundre tanker hundre måter å tenke på å leke og å snakke på hundre alltid hundre måter å lytte å undres, å synes om hundre lyster å synge og forstå hundre verdener å oppdage hundre verdener å oppfinne hundre verdener å drømme frem. Kreativitet og Glede Setter Spor Kreativitet og Glede Setter Spor Innledning Hvert år velger personalet ut en ny kunstner som skal gi barn og voksne inspirasjon til det videre prosjektarbeidet for året. Våre kriterier for å velge ut kunstner er: - Kunstneren skal være internasjonalt kjent. - Kunstneren skal ha en filosofi og kunst som er i tråd med barnehagens verdigrunnlag. - Kunstverkene skal provosere, inspirere og gi nye innfallsvinkler til prosjekttema. - Kunstneren skal ha variasjon i uttrykk og materiale. - Kunstuttrykkene skal tiltale barna og være mulig for dem å jobbe videre med. Personalet gjennomgår bilder, aktiviteter og innspill fra barna i året som har vært. Ut i fra dette reflekterer vi sammen over veien videre. Vi ser da etter; - Materiale som har inspirert barna. - Materiale vi har jobbet lite med eller har lite kjennskap til og som vi trenger å bli bedre kjent med. - Materiale som inspirerer personalet. Innimellom ber vi foreldre om innspill og hjelp til å finne aktuelle kunstnere. Dette skjer vanligvis ved skifte av 3-årig tema. 1 Kreativitet og Glede Setter Spor Ernesto Neto Bakgrunn Ernesto Neto er en brasiliansk konspetuell kunstner. Han er født i 1964 i Rio de Janerio hvor han fortsatt bor og jobber. Sin første utstilling hadde han i 2011 i Museo de Arte Contermoraneo de Monterry i Mexico. -

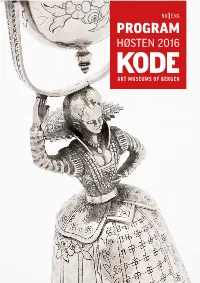

Program Høsten 2016

NO ENG PROGRAM HØSTEN 2016 1 VELKOMMEN TIL KODE #KODEBERGEN KODE er et av Nordens største museer for kunst og musikk – en unik kombinasjon av kunstmuseer og kunstnerhjem. Facebook: kodebergen Her ivaretas arven etter noen av Norges største kunstnere internasjonalt: Edvard Munch, Ole Bull, Nikolai Astrup, J.C. Dahl og Edvard Grieg. Vi tilbyr aktuell kunst, historiske gjenstander, eventyrlige naturområder og konserter i noen av verdens vakreste lokaler. Twitter: @kodebergen Våre utstillinger, kunstverk og konserter kan oppleves i KODE 1–4 i Bergen sentrum, og i komponisthjemmene til Ole Bull, Harald Sæverud og Edvard Grieg. Velkommen! Instagram: @kodebergen WELCOME TO KODE Snapchat: kode_bergen KODE is one of Scandinavia’s largest museums for art and music. It has a unique combination of art museums and composers’ homes, of visual art, historical Vil du ha informasjon om nye objects, concerts and parklands. KODE stewards almost 50,000 objects that can be utstillinger, arrangementer og experienced in four museum buildings in Bergen city centre, KODE 1–4, and in the homes of konserter? Meld deg på vårt the composers Ole Bull, Harald Sæverud and Edvard Grieg. Welcome to KODE! nyhetsbrev: kodebergen.no KODEBERGEN.NO 2 3 KODE 2 28.9. 2016 26.2. 2017 SØLVSKATTEN 1816 Nasjonsbygging gjennom dugnad og tvang: En utstilling om verdier og tillit. I år er det 200 år siden Norge fikk sin egen nasjonalbank. Bankens finansielle sikkerhet var forankret i et sølvfond, reist ved hjelp av private bidrag, på folkemunne kalt «sølvskatten». Sølvbyen Bergen øser fra en rik arv, og utstillingen gir oss anledning til å vise et utvalg av dette arvesølvet, presentert i lys av en historisk hendelse av stor nasjonal betydning. -

REISEGUIDE SUNNFJORD Førde · Gaular · Jølster · Naustdal

REISEGUIDE SUNNFJORD Førde · Gaular · Jølster · Naustdal 2018 – 2019 12 22 28 Foto: Espen Mills. Foto: Jiri Havran. Foto: Knut Utler. Astruptunet Nasjonal Turistveg Gaularfjellet Førdefestivalen Side 3 .................................................................................. Velkommen til Sunnfjord Side 4 ................................................................................. Topptureldorado sommar Side 6 ............................................................................................. Å, fagre Sunnfjord! Side 7 ..................................................................................... Topptureldorado vinter Side 8 .............................................................................................. Jølster – vår juvél! Side 9 ................................................................................................. Brebygda Jølster INNHALD Side 10 ...................................................................... Nasjonal turistveg Gaularfjellet Side 12 ................................................................. Kunst og kultur – i Astrup sitt rike Side 14 ...................................................................................................................... Fiske Side 16 ................................................... «Ete fysst» – Lokalmat som freistar ganen Side 19 ................................................................................................... Utelivet i Førde Side 20 ................................................................................ -

International Forum Oslo, Norway

INTERNATIONAL FORUM OSLO, NORWAY October NEWSLETTER 10/2016 2 Forum Diary 3 President’s Page 4 New Member 4 Coming Events 8 Reports 13 Winter Time 14 Around Oslo Number 414 1 Visiting address Arbins gt. 2, Victoria Passasjen, 5th floor Telephone 22 83 62 90 Office email [email protected] Office hours Monday, Tuesday and Thursday 10 - 12 Office Administrator Gunvor Klaveness Office Staff Vicky Alme, Lillan Akcora, Sigrid Langebrekke, May Scott, Kirsten Wensell Neighbourhood Contact Office Staff Auditor Karin Skoglund Website www.iforum.no Forum Diary DATE EVENT TIME PAGE October 20 The Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation 10:45 Sept NL November 7 H.E. Riffat Masood of Pakistan 18:45 4 November 10 Oslo Architecture Triennial 11:45 6 November 29 Christmas Lunch Asker Museum 11:30 5 Committee leaders: ART COMMITTEE Bee Ellingsen mob. 907 33 874 MONTHLY MEETINGS Laila Hægh mob. 957 54 282 Ruth Klungsøyr mob. 411 43 039 SPECIAL EVENTS Wenche Mohr mob. 901 14 259 2 From the President Dear members, The month of October started with an interesting and informative introduction to a country few of us knew much about. Ambassador Truls Erik Hanevold showed slides and talked about Bhutan in a way that convinced us all that this was a country worth visiting – a Shangri-La, and most probably, the last one of its kind. Monday the 3rd was also the day when summer decided to leave us this year; so ladies, it is time to take out the warmer clothes as we shall all have to prepare ourselves for shorter days, colder weather and maybe snow. -

Ord Fra Presidenten Spesiell Fødselsdager Special

****************************************** SPESIELL FØDSELSDAGER ORD FRA PRESIDENTEN SPECIAL BIRTHDAYS Don't we all appreciate the beautiful “Mountain Majesty” HeART sculpture at the entrance to Good Samaritan even more, now that we have seen and heard how Kathy and Ron Browne used their artistic talents to put it all together? It was a very interesting and educational program! At the Leadership Conference on February 6th many ideas were exchanged between the lodges. We thank Diane Molter and Lyle Berge for great direction. We were proud to hear that due to our increase in membership here in Stein Fjell and the installation of Storfjell Lodge, Zone 8 was able to maintain its membership numbers this year. All the lodges lent supportive ideas to one another, to attract new members and retain present ones. Think about what a good experience it would be to represent Stein Fjell as a delegate to the District Six Convention in Modesto, CA June 23-26. Our Lodge is Marian Erdal (L) gir blomster til Tillie Schopbach – allowed five delegates. Finances will be discussed at the som er 101 år gammal og Charter og Golden Medlem March Lodge meeting. If you are interested in representing Stein Fjell at the convention, have someone nominate you from the floor at this meeting. Our recent surveys revealed that the MOST WANTED extra program is a Syttende Mai Celebration. SAVE THE DATE – our Syttende Mai Celebration is set for Sunday, May 16th at the Pavilion at Good Samaritan. We thank Ron Browne for securing this facility. MARK YOUR CALENDARS! Much more information will be in the April and May Postens! As you see, there are many activities coming up! Look for the article on the upcoming dinner and show, and make your reservations with Barbara Nolin. -

Reconstructing Gardens Förord /Preface

för trädgårdshistorisk forskning Bulletin Nr 32, 2019 Reconstructing Gardens Förord /Preface Årets Bulletin innehåller till att börja med artiklar från och om se- Slutligen: Tack till alla engagerade författare, motläsare i redak- minariet Reconstructing Gardens som hölls på NMBU i Ås, Norge, tionsgruppen och till vår layoutare! Utan er skulle det inte bli nå- 11-12 oktober 2018. Den innehåller även texter som tar upp torkade gon Bulletin. blombuketter som forskningmaterial, Nikolai Astrups trädgård, ett pionprojekt i Norge, ett försök med historiska odlingssubstrat, Nu laddar vi också för seminariet i höst, 2020, då Forum firar ett NTAA-seminarium och ett par bokrapporter inom ämnet träd- 25-årsjubileum! gårds- och kulturväxthistoria. Du får även ta del av alla de stu- dentuppsatser i ämnet som producerats under året i Alnarp, Ul- A short translation in English: tuna och Göteborg. To all the devoted authors, the editorial group (see above) and Boel Nordgren (layout): thank you for all your work! This year’s Bulletin Ett stort tack för det ekonomiska bidraget vi har fått för semi- has contributions from the seminar Reconstructing Gardens in Ås, nariet i Norge, och för årets publikation, vill vi rikta till Nordisk Norway, Oct 11-12, 2018, but also texts on a peony project, trials kulturfond. Tack också till School of Landscape Architecture på with historic soil mixtures, a report from a Nordic seminar, info NMBU, Ås, för ert ekonomiska stöd och värdskap vid seminariet. on student theses and book reports. Ett stort tack till Madeleine von Essen och Mette Eggen, som gui- dade under exkursionen till Spydeberg, till Karsten Jørgensen som /Anna Jakobsson guidade i Ekeberg park, samt till Annegreth Dietze och Bjørn An- Redaktör för Bulletinen ders Fredriksen som planerade huvuddelarna av det fina semina- Editor rieprogrammet. -

Storberget Resigns from Post

(Periodicals postage paid in Seattle, WA) TIME-DATED MATERIAL — DO NOT DELAY Arts & Style Julegaveforslag: Special Issue Review of Til din fiende: tilgivelse. Til en motstander: toleranse. Til en venn: ditt Welcome to the “Luminous hjerte. Til en kunde: service. Til alle: Christmas Gift nestekjærlighet. Til hvert barn: et godt Modernism” eksempel. Til deg selv - respekt. Guide 2011! Read more on page 3 – Oren Arnold Read more on pages 8 – 18 Norwegian American Weekly Vol. 122 No. 42 November 18, 2011 Established May 17, 1889 • Formerly Western Viking and Nordisk Tidende $1.50 per copy Norway.com News Find more at www.norway.com Storberget resigns from post News City officials in Oslo, faced with Grete Faremo budget cuts, considered drop- ping their annual gift of large appointed city Christmas trees to Lon- don, Reykjavik and Rotterdam, as Minister of to save money. They appar- ently didn’t want to be seen as Justice Scrooge, though, and the trees will be sent as usual. (blog.norway.com/category/ STAFF COMPILATION news) Norwegian American Weekly Sports Norway’s cross country ace, Pet- After six years of serving as ter Northug, captured third place Norway’s Minister of Defense and in the 15km seaason opener in the Police, Knut Storberget stepped Bruksvallarn, Sweden on Sat- down from his post on Nov. 11. urday. Maurice Manificat of He was one of Norway’s lon- France won, with Sweden’s Jo- gest-serving justice ministers ever. han Olson in 2nd. Northug was “I have four good reasons to very pleased with his placing resign,” he told NRK, referring to in the firsts race of the season, his wife and three daughters back considering the lack of snow home in Elverum, Hedmark Coun- this winter. -

Og Saa Kommer Vi Til Brevskriveren Selv, Jo Tak Hun Har Det Upaaklageligt»

«Og saa kommer vi til brevskriveren selv, jo tak hun har det upaaklageligt» Kitty Kiellands brev til Dagmar Skavlan, Eilif Peterssen og Arne Garborg Sofie Steensnæs Engedal NOR4395 Masteroppgave i nordisk, særlig norsk, litteraturvitenskap Institutt for lingvistiske og nordiske studier Det humanistiske fakultet UNIVERSITETET I OSLO Vår 2019 II «Og saa kommer vi til brevskriveren selv, jo tak hun har det upaaklageligt» Kitty Kiellands brev til Dagmar Skavlan, Eilif Peterssen og Arne Garborg Sofie Steensnæs Engedal Selvportrett 1887 Kitty L. Kielland/Eier: Nasjonalmuseet III IV © Sofie Steensnæs Engedal 2019 «Og saa kommer vi til brevskriveren selv, jo tak hun har det upaaklageligt». Kitty Kiellands brev til Dagmar Skavlan, Eilif Peterssen og Arne Garborg Sofie Steensnæs Engedal http://www.duo.uio.no Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo V VI VII Sammendrag Kitty Lange Kielland (1843–1914) var både en engasjert samfunnsdebattant og den første store norske kvinnelige landskapsmaleren. I denne masteroppgaven foretar jeg en tematisk analyse av brevene hennes til Dagmar Skavlan, Eilif Peterssen og Arne Garborg, ved å se på hvordan hun skriver om kropp, helse, sosialt liv, kunstarbeidet, vær, geografi, kvinnesaken og selve brevskrivingen. Den russiske litteraturviteren og filosofen Mikhail Bakhtin hevdet at ingen ytringer står isolerte, og dette kommer til syne i analysen min, som viser at hun er en svært selvbevisst brevskriver som forholder seg ulikt til de tre mottakerne og skriver forskjellig til søsteren, maleren og forfatteren. Ved å ta utgangspunkt i disse brevene viser jeg en større bredde hos Kitty Kielland som brevskriver enn det jeg mener har blitt lagt frem før. Til tross for å ha vært fremtredende på flere arenaer finner jeg at Kitty Kielland til stadighet i ettertidens fremstillinger blir satt i relasjon til menn, med spesielt en interesse for å grave i kjærlighetslivet hennes. -

Nationality and Community

Nationality and Community in Norwegian Art Criticism around 1900 Tore Kirkholt Back in 1857, the Norwegian writer Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson (1832– 1910) considered the establishment of a theatre institution in Christiania (Oslo) as a vital necessity for the nation. One of his main arguments for having such an institution in Norway was what he saw as a lack of certainty, of self-confidence, in the people of Norway. This lack of confidence was easy to spot when a Norwegian stepped ashore on a foreign steamer-quay. He would be groping for his sense of ease, and end up conducting himself in a ‘rough, short, almost violent manner’, which gave an uncomfortable impression.1 In Bjørnson’s narrative, this feeling of uncertainty relates to the theme of modernity. Bjørnson described his home country as a small America – where factories and mining were expanding – dominated by the sheer material life. The solidity of tradition had gone; it was a time of flux, decoupled from the past. Modernity’s splitting of traditions was a common theme in most European countries, so why was the rough, short and violent behaviour so characteristic of Norwegians? According to Bjørnson, it was because Norway did not have an artistic culture that could negotiate the feeling of fragmentation and uncertainty. Arts such as theatre, music, painting and statuary could express what was common in what seemed like fragments. The arts could 1 Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, ‘En Stor- unite. However, cultural institutions that could support the arts thingsindstilling’, Morgenbladet, 21 June 1857. ‘Man kan f. Ex. paa en suffered from a lack of funding, a vital deficiency of Norwegian udenlandsk Damskibsbrygge meget godt se, det er en Normand, som society. -

Musikkekteparet Olaus Andreas Grøndahl Og Agathe Backer Grøndahl

Musikkekteparet Olaus Andreas Grøndahl og Agathe Backer Grøndahl En fellesbiografi Nina Steihaug Masteroppgave Institutt for arkeologi, historie, kultur- og religionsvitenskap UNIVERSITETET I BERGEN 15.05.2014 II Musikkekteparet Olaus Andreas Grøndahl (1847–1923) og Agathe Backer Grøndahl (1847–1907) En fellesbiografi III © Forfatter År 2014 Tittel: Musikkekteparet Olaus Andreas Grøndahl og Agathe Backer Grøndahl. En fellesbiografi Forfatter: Nina Steihaug https://bora.uib.no/ IV Sammendrag/Summary The title of the thesis is: A Marriage of Musicians. Agathe Backer Grøndahl and Olaus Andreas Grøndahl. A Collective Biography. The theme is the marriage of Agathe Backer Grøndahl (1847– 1907) and Olaus Andreas Grøndahl (1847–1923) (also known as O. A. Grøndahl and Olam Grøndahl) of Kristiania1 in Norway. The couple were married in 1875 and both were prominent musicians during the second half of the 19th century. Agathe was a famous pianist with an international career, a prolific composer of piano and songs and a piano teacher for a new generation of Norwegian professional pianists. Olam started his musical career as a singer, a tenor soloist, and composer, but later acted as a choir master and conductor of several male and mixed choirs and served as a music teacher at numerous schools. He also participated in the development of the music teaching in Norway, acting for the Government, at the time of the formation of the new national state. The couple lived in Kristiania, had three children and led a comparatively quiet home life, but travelled extensively at times, mostly on separate musical tours. The problem addressed is how a married woman by the end of the 19th century could be a professional musician, a public figure and earn her own money for the support of the family, take her space in the public sphere as an extremely popular concert pianist and at the same time being a conventional upper society housewife. -

Those Almond-Eyed Children of the Far East

Those almond-eyed children of the Far East. An exploration of japonist thought and Japanophilia in fin-de-siècle Nordic painters. Word count: 28948 Charlotte Van Hulle Student number: 01504426 Supervisor(s): Prof. Dr. Mick Deneckere A dissertation submitted to Ghent University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Oriental Languages and Cultures–Japanese Language and Culture. Academic year: 2019–2020 PREAMBLE CONCERNING COVID-19 Due to the outbreak of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic of 2020, it should be kept in mind that the research conducted for the purpose of this thesis could not take place as originally intended. The outbreak of the pandemic had direct consequences for the process of completing this master’s thesis—at the time when I began my research, I resided in Finland as a student at the University of Helsinki. A significant part of this thesis relied on the access to source material, as well as access to translation by native speakers of Finnish and Swedish, that this location provided. However, due to the outbreak of the COVID-19 virus, I was unable to stay in Finland, and saw myself forced to leave the country. Before the borders closed, I flew out to Sweden, to be with my partner and family-in-law during this crisis. I was, overall, among those fortunate enough to be able to move ahead with their research throughout the pandemic. That is, no field work was conducted for the purpose of this thesis’ argument, meaning that closed borders and national lockdowns had no bearing on my research as such.