Marnie Hay Book Review1x

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Going Against the Flow: Sinn Féin´S Unusual Hungarian `Roots´

The International History Review, 2015 Vol. 37, No. 1, 41–58, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07075332.2013.879913 Going Against the Flow: Sinn Fein’s Unusual Hungarian ‘Roots’ David G. Haglund* and Umut Korkut Can states as well as non-state political ‘actors’ learn from the history of cognate entities elsewhere in time and space, and if so how and when does this policy knowledge get ‘transferred’ across international borders? This article deals with this question, addressing a short-lived Hungarian ‘tutorial’ that, during the early twentieth century, certain policy elites in Ireland imagined might have great applicability to the political transformation of the Emerald Isle, in effect ushering in an era of political autonomy from the United Kingdom, and doing so via a ‘third way’ that skirted both the Scylla of parliamentary formulations aimed at securing ‘home rule’ for Ireland and the Charybdis of revolutionary violence. In the political agenda of Sinn Fein during its first decade of existence, Hungary loomed as a desirable political model for Ireland, with the party’s leading intellectual, Arthur Griffith, insisting that the means by which Hungary had achieved autonomy within the Hapsburg Empire in 1867 could also serve as the means for securing Ireland’s own autonomy in the first decades of the twentieth century. This article explores what policy initiatives Arthur Griffith thought he saw in the Hungarian experience that were worthy of being ‘transferred’ to the Irish situation. Keywords: Ireland; Hungary; Sinn Fein; home rule; Ausgleich of 1867; policy transfer; Arthur Griffith I. Introduction: the Hungarian tutorial To those who have followed the fortunes and misfortunes of Sinn Fein in recent dec- ades, it must seem the strangest of all pairings, our linking of a party associated now- adays mainly, if not exclusively, with the Northern Ireland question to a small country in the centre of Europe, Hungary. -

Secret Societies and the Easter Rising

Dominican Scholar Senior Theses Student Scholarship 5-2016 The Power of a Secret: Secret Societies and the Easter Rising Sierra M. Harlan Dominican University of California https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2016.HIST.ST.01 Survey: Let us know how this paper benefits you. Recommended Citation Harlan, Sierra M., "The Power of a Secret: Secret Societies and the Easter Rising" (2016). Senior Theses. 49. https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2016.HIST.ST.01 This Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Dominican Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Dominican Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE POWER OF A SECRET: SECRET SOCIETIES AND THE EASTER RISING A senior thesis submitted to the History Faculty of Dominican University of California in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Arts in History by Sierra Harlan San Rafael, California May 2016 Harlan ii © 2016 Sierra Harlan All Rights Reserved. Harlan iii Acknowledgments This paper would not have been possible without the amazing support and at times prodding of my family and friends. I specifically would like to thank my father, without him it would not have been possible for me to attend this school or accomplish this paper. He is an amazing man and an entire page could be written about the ways he has helped me, not only this year but my entire life. As a historian I am indebted to a number of librarians and researchers, first and foremost is Michael Pujals, who helped me expedite many problems and was consistently reachable to answer my questions. -

Volunteer Women: Militarized Femininity in the 1916 Easter Rising

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons War and Society (MA) Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-20-2019 Volunteer Women: Militarized Femininity in the 1916 Easter Rising Sasha Conaway Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/war_and_society_theses Part of the Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Conaway, Sasha. Volunteer Women: Militarized Femininity in the 1916 Easter Rising. 2019. Chapman University, MA Thesis. Chapman University Digital Commons, https://doi.org/10.36837/chapman.000079 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in War and Society (MA) Theses by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Volunteer Women: Militarized Femininity in the 1916 Easter Rising A Thesis by Sasha Conaway Chapman University Orange, CA Wilkinson College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in War and Society May 2019 Committee in Charge Jennifer Keene, Ph.D., Chair Charissa Threat, Ph.D. John Emery, Ph. D. May 2019 Volunteer Women: Militarized Femininity in the 1916 Easter Rising Copyright © 2019 by Sasha Conaway iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my parents, Elda and Adam Conaway, for supporting me in pursuit of my master’s degree. They provided useful advice when tackling such a large project and I am forever grateful. I would also like to thank my advisor, Dr. -

Bulmer Hobson and the Nationalist Movement in Twentieth-Century Ireland by Marnie Hay Review By: Fergal Mccluskey Source: Irish Historical Studies, Vol

Review Reviewed Work(s): Bulmer Hobson and the nationalist movement in twentieth-century Ireland by Marnie Hay Review by: Fergal McCluskey Source: Irish Historical Studies, Vol. 37, No. 145 (May 2010), pp. 158-159 Published by: Cambridge University Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20750083 Accessed: 31-12-2019 18:31 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Irish Historical Studies This content downloaded from 82.31.34.218 on Tue, 31 Dec 2019 18:31:59 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 158 Irish Historical Studies BULMER HOBSON AND THE NATIONALIST MOVEMENT IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY IRELAND. By Mamie Hay. Pp 272, illus. Manchester: Manchester University Press. 2009. ?55 hardback; ?18.99 paperback. Bulmer Hobson's formative influence in numerous political and cultural organisations begs the question as to why, until now, his autobiographical Ireland: yesterday and tomorrow (1968) remained the only consequential account of his career. Dr Hay expresses little surprise, however, at this historiographical gap. In fact, Hobson's position as 'worsted in the political game' (p. 1) serves as this book's premise. -

Roinn Cosanta

ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS. DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 1,765. Witness His Excellency, Seán T. O'Kelly, Árus an Uachtaráin, Phoenix Park, Dublin. Identity. Speaker, Dáil Éireann, 1920; Irish Representative, Paris & Rome, 1920-21; Minister for Local Government & Finance, 1932-45; President of Ireland, 1945-59. Subject. National activities, 1898-1921. Conditions, if any, Stipulated by Witness. Nil. File No S.9. Form B.S.M.2 DREACHT/4 A very considerable revival of national feeling and sentiment was caused as a result of the many meetings and demonstrations held in Dublin and in many parts of the co in celebration of the Centenary of the Insurrection of 17 Dublin, I think, was particularly affected. There were nationalist organisations established during the year 189 a year or two following, '98 Clubs became a fairly common of national political life in all parts of the City, and of the country. For a number of years after the '98 Ce demonstations took place in the counties where there had considerable activity in 1798, and monuments were erect connection with the unveiling of the monuments, demonstrd were held to which large numbers of people travelled, and these meetings speeches urging a revival of national sent and national activity of various kinds were made by peop prominently associated with the national movement. As far as I remember, all sections of the, what wo the called Gaelic movement, were associated with Centenary celebrations. The Parliamentary Party of the d took a prominent part in it, and the various sections of the deman tatiam associated but these meetings and demonstration themselves4, were utilised by a small but effective group of people who the 2. -

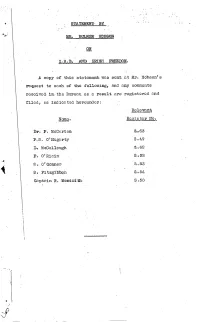

STATEMENT by MR. BULMER HOBSON on I. R. B. and IRISH FREEDOM a Copy of This Statement Was Sent. at Mr. Hobson's Request to Each

STATEMENT BY MR. BULMER HOBSON ON I. R. B. AND IRISH FREEDOM A copy of this statement was sent. at Mr. Hobson's request to each of the following, and any comments received in the Bureau as a result are registered and filed, as. indicated hereunder: Relevant Name Rogister NO. Dr. P McCartan S.63 P.S, O'Hogarty S.49 D, McCuliough S,62 P. O'Rinin S,32 S. 0'Connor S.53 S. Fitzgihbon S.54 Captain R. Montcith S.50 PÁDRAIG PEARSE. After The formation of the Irish Volunteers in October, 1913, Pádraig Pearse was sworn in by me as a member of the I.R.B. in December of that year. I cannot recollect which Circle. The circumstances leading to this were as follows: Being in financial difficulties with his school, St. Enda's, Rathfarnham, and being afraid of bankruptcy, Pearse came to me in December 1913 with his problem. He had started his school on a promise of £500 which had never materialised. I arranged a lecture tour for him in the United States after correspondence with John Devoy, of the stare of NewYork Joe McGarrity, Judge Keogh of the Supreme Court, and, I think, John Quinn. When these arrangements were made, and in view of the fact that pearse would almost certainly have been brought in to the I.R.B. at a very early date, I swore him in before his departure for the States. Pearse went to the United States. I followed a fortnight later. Pearse was quite unaware of my intention to go there and was surprised when I turned up. -

Sinn Féin and the Labour Movement Arthur Griffith and Sinn Féin Griffith

3.0 Those who Set the Stage 3.3 Those with other agenda: Sinn Féin and the labour movement 3.3.1 Arthur Griffith and Sinn Féin Griffith and Sinn Féin contributed directly to the Rising by his brilliant propaganda and by radicalising a generation of Irish nationalists. Arthur Griffith (1871-1922) was born at 61 Upper Dominick Street, Dublin and was educated at the Christian Brothers’ schools at Strand Street and St Mary’s Place. He worked as a printer at the Irish Independent, spending much of his spare time in debating societies where he came under the influence of the journalist and poet William Rooney. In 1893 they founded the Celtic Literary Society which promoted the study of Irish language, literature, history and music, its political slogan being ‘independent action’. Griffith was also active in the Gaelic League in which Rooney was a teacher. He was a member of the separatist Irish Republican Brotherhood up until 1910, after which time he generally repudiated the use of physical force for political ends. Following a period in South Africa where he worked in the gold mines and gave some assistance to the Boers, he became editor of the new weekly radical paper, the United Irishman, first published in Dublin in March 1899. In 1900, together with Rooney he established Cumann na nGaedheal, an umbrella body designed to co-ordinate the activities of the various groups endeavouring to counteract the continuing anglicisation of the country. After the failure of the Home Rule bills of 1886 and 1893, Griffith had little faith in the current mode of parliamentary action. -

HQ. Sean . 'Duffy, 7. Pall Faggfthg COURTS 1919

REG. NO. OF THE COLLECTION CD. HQ. NAME OF DONOR Sean . 'Duffy, SUB. OBSERVATIONS NO. DOCUMENT FORMAT Etc. PAlL faggftHg COURTS 1919 - 1922. Croup 5. Appointments £c Conferences etc. of Parish & District Court Justices, 1921-22. Circular, undated, from Minister for Home Affairs instructing that a meeting be called of all District Justices - (annotated "Issued during the Truce period"). Republican Court Convention at Annacurra, Saturday, 24tb September, 1921 - Suggested Agen^i. Letter, 28th September, 1921, from Mis* Barton re her intention net to attend a meeting at Togher, Roundwood, on following Thursday. List of persons, addresses tions in connection v/ith meeting at Togher, 29/9/1921 Copy of Circular to be sent to various Registrars, 21st October, 1921, from Sean Iff* Ua Dubhthaigh re proposed meeting of District Justices & Clerks. Election of Parish & District Justices - Convention for East 7/icklow Constituency at Hioklqw on 22nd October, 1921: (a) Notice 10/10/21 convening meeting for 22/10/1921; (b) Suggested Agenda; (c) Letter, 21st October, 1921, from llicheal Ua Duinn, 0/C *F* Coy., Battn. , 2, Enniskerrv, regretting inability to attend convention; (d) Letter, 22nd October, 1921, from Niss Barton, Glendalough House, regretting inability to attend convention; (e) List of personnel in attendance and notes of jjroceedings. 7. Parish Conventions, V/icklow 1st November, 1921, Enniskerry 1st November, 1921, Bray 27th October, 1921, & Delgany 1st November, 1921: (a) Draft & copy of convention notice, 24th October, 1921; (b) Note of Proceedings at Delgany Convention, 1st November, 1921. Papers relating to establishment of Courts in East V/icklow & North Vfexford, October-November, 1921. -

View/Download

PART EIGHT OF TEN SPECIAL MAGAZINES IN PARTNERSHIP WITH 1916 AND COLLECTION Thursday 4 February 2016 www.independent.ie/1916 CONSTANCE MARKIEVICZ AND THE WOMEN OF 1916 + Nurse O’Farrell: airbrushed from history 4 February 2016 I Irish Independent mothers&babies 1 INTRODUCTION Contents Witness history 4 EQUALITY AGENDA Mary McAuliffe on the message for women in the Proclamation from GPO at the 6 AIRBRUSHED OUT Nurse Elizabeth O’Farrell’s role was cruelly excised from history heart of Rising 7 FEMALE FIGHTERS Joe O’Shea tells the stories of the women who saw 1916 action WITH its central role newlyweds getting their appeal to an international 8 ARISTOCRATIC REBEL in Easter Week, it was photos taken, the GPO audience, as well as Conor Mulvagh profiles the inevitable focus would has always been a seat of those closer to Dublin 1 enigmatic Constance Markievicz fall on the GPO for the “gathering, protest and who want a “window on Rising commemorations. celebration”, according to Dublin at the time” and its 9 ‘WORLD’S WILD REBELS’ And with the opening of McHugh. When it comes residents. Lucy Collins on Eva Gore- the GPO Witness History to its political past, the As part of the exhibition, Booth’s poem ‘Comrades’ exhibition, An Post hopes immersive, interactive visitors will get to see to immerse visitors in the centre does not set out to inside a middle-class 10 HEART OF THE MATER building’s 200-year past. interpret the events of the child’s bedroom in a Kim Bielenberg delves into the According to Anna time. -

Those Who Set the Stage Republicans and Those Who Would Resort to Physical Force Bulmer Hobson and Denis Mccullough They Contrib

3.0 Those who Set the Stage 3.2 Republicans and those who would resort to physical force 3.2.1 Bulmer Hobson and Denis McCullough They contributed to the Rising by revitalising the Irish Republican Brotherhood and promoting the Irish Volunteers. Throughout the nineteenth century the republican movement tended to wax and wane: it experienced a particularly low ebb for the ten years following the death of Parnell in 1891. At the time most nationalists looked to parliamentary politics as the only feasible and moral means of advancing Ireland’s cause. Home Rule was the objective: most people believed it was inevitable and that it would transform the Irish economy. While some hoped that it would lead to eventual separation from Britain, most people accepted Ireland’s role as part of the United Kingdom - the most powerful empire on earth: for many their situation was not particularly irksome. While dormant, the republican tradition, however, was not dead. There was always a minority of people who believed that Britain had no legitimate claim to jurisdiction over Ireland. They also felt that Home Rule would bring little material benefit to Ireland and that the only worthwhile objective was absolute independence. Considering how well-nigh impossible it was to wrest any concession from Britain by constitutional means (as was the experience of O’Connell with Repeal of the Union and of Parnell with Home Rule), the only option for republicans appeared to be physical force. 1 3.2.1 Bulmer Hobson and Denis McCullough In the early years of the twentieth century republicanism underwent a revival in Belfast. -

The Dlr Roger Casement Summer School / Festival 2019

The dlr Roger Casement Summer School / Festival 2019 dlr Lexicon, Haigh Terrace, Moran Park, Dún Laoghaire Friday 30th August to Sunday 1st September Tickets €35 (includes free entry to social) or €10 per Session Full details of the 3 day programe available www.rogercasementsummerschool.ie Email or telephone for info /tickets: [email protected] Facebook: DLR Roger Casement Summer School Tel: 087-2611597 / 086-0572005 Social: Saturday, 31st August Join us for an evening of music and song in the Dún Laoghaire Club, Eblana Ave, Dún Laoghaire at 8.30pm – €10 per ticket Summer School Festival Speakers 2019 ABDULAZIZ ALMOAYYAD and an MA (English) from UCD (1970). He joined the Abdulaziz Almoayyad is a Saudi dissident Department of Foreign Affairs as Third Secretary in who has been resident in Ireland for the past 1970 and subsequently served in New York, Geneva and 5 years. He is regularly interviewed by Al Brussels. Appointed as ambassador in 1990, initially to Jazeera, the BBC and other media outlets on Iran, subsequently in Brussels (EU), Italy (plus Malta, Libya the parlous state of human rights, especially and UN-FAO) and Austria (plus UN and IAEA, Vienna). women’s rights, in Saudi Arabia. Before He acted as Ambassador, head of the Task Force for the coming to Ireland he had a long career as a publisher Irish Chairmanship of the Organisation for Security and and marketer. He was collaborating with the Saudi journalist Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) in 2012, following which Jamal Khashoggi just prior to Khashoggi’s assassination in he retired from the Foreign Service. -

Art Ó Briain Papers

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 150 Art Ó Briain Papers (MSS 2141, 2154-2157, 5105, 8417-61) Accession No. 1410 The papers of Art Ó Briain (c.1900-c.1945) including records and correspondence of the London Office of Dáil Eireann (1919-22), papers of the Irish Self-Determination League of Great Britain (1919-25), the Gaelic League of London (1896-1944) and Sinn Féin (1918-25). The collection includes correspondence with many leading figures in the Irish revolution, material on the truce and treaty negotiations and the cases of political prisoners (including Terence MacSwiney). Compiled by Owen McGee, 2009 1 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................. 4 I. The Gaelic League of London (1896-1944) ............................................................... 10 II. Ó Briain’s earliest political associations (1901-16) ................................................. 23 III. Ó Briain’s work for Irish political prisoners (1916-21)........................................ 28 III.i. Irish National Aid Association and Volunteer Dependants Fund......................... 28 III.ii. The Irish National Relief Fund and The Irish National Aid (Central Defense Fund)............................................................................................................................. 30 III.iii. The hunger-strike and death of Terence MacSwiney......................................... 42 IV. Ó Briain’s