Bony Excrescences in Skull Base and Upper Extremity, P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clinical Features of Benign Tumors of the External Auditory Canal According to Pathology

Central Annals of Otolaryngology and Rhinology Research Article *Corresponding author Jae-Jun Song, Department of Otorhinolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, Korea University College of Clinical Features of Benign Medicine, 148 Gurodong-ro, Guro-gu, Seoul, 152-703, South Korea, Tel: 82-2-2626-3191; Fax: 82-2-868-0475; Tumors of the External Auditory Email: Submitted: 31 March 2017 Accepted: 20 April 2017 Canal According to Pathology Published: 21 April 2017 ISSN: 2379-948X Jeong-Rok Kim, HwibinIm, Sung Won Chae, and Jae-Jun Song* Copyright Department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Korea University College © 2017 Song et al. of Medicine, South Korea OPEN ACCESS Abstract Keywords Background and Objectives: Benign tumors of the external auditory canal (EAC) • External auditory canal are rare among head and neck tumors. The aim of this study was to analyze the clinical • Benign tumor features of patients who underwent surgery for an EAC mass confirmed as a benign • Surgical excision lesion. • Recurrence • Infection Methods: This retrospective study involved 53 patients with external auditory tumors who received surgical treatment at Korea University, Guro Hospital. Medical records and evaluations over a 10-year period were examined for clinical characteristics and pathologic diagnoses. Results: The most common pathologic diagnoses were nevus (40%), osteoma (13%), and cholesteatoma (13%). Among the five pathologic subgroups based on the origin organ of the tumor, the most prevalent pathologic subgroup was the skin lesion (47%), followed by the epithelial lesion (26%), and the bony lesion (13%). No significant differences were found in recurrence rate, recurrence duration, sex, or affected side between pathologic diagnoses. -

Bone and Soft Tissue Tumors Have Been Treated Separately

EPIDEMIOLOGY z Sarcomas are rare tumors compared to other BONE AND SOFT malignancies: 8,700 new sarcomas in 2001, with TISSUE TUMORS 4,400 deaths. z The incidence of sarcomas is around 3-4/100,000. z Slight male predominance (with some subtypes more common in women). z Majority of soft tissue tumors affect older adults, but important sub-groups occur predominantly or exclusively in children. z Incidence of benign soft tissue tumors not known, but Fabrizio Remotti MD probably outnumber malignant tumors 100:1. BONE AND SOFT TISSUE SOFT TISSUE TUMORS TUMORS z Traditionally bone and soft tissue tumors have been treated separately. z This separation will be maintained in the following presentation. z Soft tissue sarcomas will be treated first and the sarcomas of bone will follow. Nowhere in the picture….. DEFINITION Histological z Soft tissue pathology deals with tumors of the classification connective tissues. of soft tissue z The concept of soft tissue is understood broadly to tumors include non-osseous tumors of extremities, trunk wall, retroperitoneum and mediastinum, and head & neck. z Excluded (with a few exceptions) are organ specific tumors. 1 Histological ETIOLOGY classification of soft tissue tumors tumors z Oncogenic viruses introduce new genomic material in the cell, which encode for oncogenic proteins that disrupt the regulation of cellular proliferation. z Two DNA viruses have been linked to soft tissue sarcomas: – Human herpes virus 8 (HHV8) linked to Kaposi’s sarcoma – Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) linked to subtypes of leiomyosarcoma z In both instances the connection between viral infection and sarcoma is more common in immunosuppressed hosts. -

CASE REPORT Intradermal Nevus of the External Auditory Canal

Int. Adv. Otol. 2009; 5:(3) 401-403 CASE REPORT Intradermal Nevus of the External Auditory Canal: A Case Report Sedat Ozturkcan, Ali Ekber, Riza Dundar, Filiz Gulustan, Demet Etit, Huseyin Katilmis Department of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery ‹zmir Atatürk Research and Training Hospital, Ministry of Health, ‹ZM‹R-TURKEY (SO, AE, FG, DE, HK) Department of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery Etimesgut Military Hospital , ANKARA-TURKEY (RD) Intradermal nevus is the most common skin tumor in humans; however, its occurrence in the external auditory canal (EAC) is uncommon. The clinical manifestations of pigmented nevus of the EAC have been reported to include ear fullness, foreign body sensation, hearing impairment, and otalgia, but some cases were asymptomatic and were found incidentally. The treatment of choice for a symptomatic intradermal nevus in the EAC is complete excision. There has been no recurrence reported in the literature . A pedunculated, papillomatous hair-bearing lesion was detected in the external auditory canal of the patient who was on follow-up for pruritus. Clinical and pathologic features of an intradermal nevus of the external auditory canal are presented, and the literature reviewed. Submitted : 14 October 2008 Revised : 01 July 2009 Accepted : 09 July 2009 Intradermal nevus is the most common skin tumor in left external auditory canal. Otomicroscopic humans; however, its occurrence in the external examination revealed a pedunculated, papillomatous auditory canal (EAC) is uncommon [1-4]. Intradermal hair-bearing lesion in the postero-inferior cartilaginous nevus is considered to be a form of benign cutaneous portion of the external auditory canal (Figure 1). -

A Case of Intradermal Melanocytic Nevus with Ossification (Nevus of Nanta)

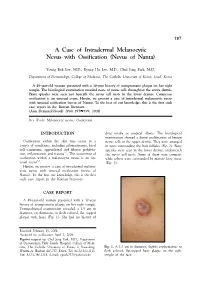

197 A Case of Intradermal Melanocytic Nevus with Ossification (Nevus of Nanta) Young Bok Lee, M.D., Kyung Ho Lee, M.D., Chul Jong Park, M.D. Department of Dermatology, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea A 49-year-old woman presented with a 30-year history of asymptomatic plaque on her right temple. The histological examination revealed nests of nevus cells throughout the entire dermis. Bony spicules were seen just beneath the nevus cell nests in the lower dermis. Cutaneous ossification is an unusual event. Herein, we present a case of intradermal melanocytic nevus with unusual ossification (nevus of Nanta). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first such case report in the Korean literature. (Ann Dermatol (Seoul) 20(4) 197∼199, 2008) Key Words: Melanocytic nevus, Ossification INTRODUCTION drug intake or medical illness. The histological examination showed a dense proliferation of benign Ossification within the skin may occur in a nevus cells in the upper dermis. They were arranged variety of conditions, including pilomatricoma, basal in nests surrounding the hair follicles (Fig. 2). Bony cell carcinoma, appendageal and fibrous prolifera- spicules were seen in the lower dermis, underneath 1,2 tion, inflammation and trauma . The occurrence of the nevus cell nests. Some of them were compact ossification within a melanocytic nevus is an un- while others were surrounded by mature fatty tissue 3-5 usual event . (Fig. 3). Herein, we present a case of intradermal melano- cytic nevus with unusual ossification (nevus of Nanta). To the best our knowledge, this is the first such case report in the Korean literature. -

Basal Cell Carcinoma Associated with Non-Neoplastic Cutaneous Conditions: a Comprehensive Review

Volume 27 Number 2| February 2021 Dermatology Online Journal || Review 27(2):1 Basal cell carcinoma associated with non-neoplastic cutaneous conditions: a comprehensive review Philip R Cohen MD1,2 Affiliations: 1San Diego Family Dermatology, National City, California, USA, 2Touro University California College of Osteopathic Medicine, Vallejo, California, USA Corresponding Author: Philip R Cohen, 10991 Twinleaf Court, San Diego, CA 92131-3643, Email: [email protected] pathogenesis of BCC is associated with the Abstract hedgehog signaling pathway and mutations in the Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) can be a component of a patched homologue 1 (PCTH-1) transmembrane collision tumor in which the skin cancer is present at tumor-suppressing protein [2-4]. Several potential the same cutaneous site as either a benign tumor or risk factors influence the development of BCC a malignant neoplasm. However, BCC can also concurrently occur at the same skin location as a non- including exposure to ultraviolet radiation, genetic neoplastic cutaneous condition. These include predisposition, genodermatoses, immunosuppression, autoimmune diseases (vitiligo), cutaneous disorders and trauma [5]. (Darier disease), dermal conditions (granuloma Basal cell carcinoma usually presents as an isolated faciale), dermal depositions (amyloid, calcinosis cutis, cutaneous focal mucinosis, osteoma cutis, and tumor on sun-exposed skin [6-9]. However, they can tattoo), dermatitis, miscellaneous conditions occur as collision tumors—referred to as BCC- (rhinophyma, sarcoidal reaction, and varicose veins), associated multiple skin neoplasms at one site scars, surgical sites, systemic diseases (sarcoidosis), (MUSK IN A NEST)—in which either a benign and/or systemic infections (leischmaniasis, leprosy and malignant neoplasm is associated with the BCC at lupus vulgaris), and ulcers. -

Osteoid Osteoma and Your Everyday Practice

n Review Article Instructions 1. Review the stated learning objectives at the beginning cme ARTICLE of the CME article and determine if these objectives match your individual learning needs. 2. Read the article carefully. Do not neglect the tables and other illustrative materials, as they have been selected to enhance your knowledge and understanding. 3. The following quiz questions have been designed to provide a useful link between the CME article in the issue Osteoid Osteoma and your everyday practice. Read each question, choose the correct answer, and record your answer on the CME Registration Form at the end of the quiz. Petros J. Boscainos, MD, FRCSEd; Gerard R. Cousins, MBChB, BSc(MedSci), MRCS; 4. Type or print your full name and address and your date of birth in the space provided on the CME Registration Form. Rajiv Kulshreshtha, MBBS, MRCS; T. Barry Oliver, MBChB, MRCP, FRCR; 5. Indicate the total time spent on the activity (reading article and completing quiz). Forms and quizzes cannot be Panayiotis J. Papagelopoulos, MD, DSc processed if this section is incomplete. All participants are required by the accreditation agency to attest to the time spent completing the activity. educational objectives 6. Complete the Evaluation portion of the CME Regi stration Form. Forms and quizzes cannot be processed if the Evaluation As a result of reading this article, physicians should be able to: portion is incomplete. The Evaluation portion of the CME Registration Form will be separated from the quiz upon receipt at ORTHOPEDICS. Your evaluation of this activity will in no way affect educational1. -

Basal Cell Carcinoma with Osteoma Cutis

Open Access Case Report DOI: 10.7759/cureus.3170 Basal Cell Carcinoma with Osteoma Cutis Stella X. Chen 1 , Philip R. Cohen 2 1. School of Medicine, University of California, San Diego 2. Dermatologist, San Diego Family Dermatology, San Diego, USA Corresponding author: Stella X. Chen, [email protected] Abstract Osteoma cutis is the formation of bone within the skin. It can present as either primary osteoma cutis or secondary osteoma cutis. Secondary osteoma cutis is more common and is associated with inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic disorders, including basal cell carcinoma. A 79-year-old Caucasian man without underlying kidney disease or calcium abnormalities presented with a basal cell carcinoma with osteoma cutis on the chin. Basal cell carcinoma with osteoma cutis has seldom been described; however, the occurrence of this phenomenon may be more common than suggested by the currently published literature. The preferred treatment is surgical excision—with or without using Mohs micrographic technique. When the histopathologic examination reveals bone formation in the skin, clinicians should consider the possible presence of an adjacent malignancy, such as a basal cell carcinoma. Categories: Dermatology, Oncology Keywords: basal, bone, calcium, calcinosis, carcinoma, cell, cutis, ossification, osteoma Introduction Basal cell carcinoma is the most common type of skin cancer. Osteoma cutis is the formation of bone within the skin; it can occur either as a distinct cutaneous entity or associated with other conditions. In primary osteoma cutis, idiopathic ossification occurs and can be congenital, acquired, or related to Albright’s hereditary osteodystrophy and fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Secondary osteoma cutis is more commonly seen and may be associated with infectious, inflammatory, or neoplastic disorders, including basal cell carcinoma. -

Orbital Osteoma

Orbital Osteoma Gina M. Rogers, MD and Keith D. Carter, MD June 3, 2011 Chief Complaint: Left eyelid mass History of Present Illness: A healthy 20 year-old woman presented to the Oculoplastics Clinic with a 9- month history of left upper lid droopiness. Over the same period of time, she also noted a “bump” at the nasal aspect of her upper eyelid and felt that it was increasing in size. She denied any vision changes, ocular pain, pain with eye movement, or headaches. A complete review of systems was negative. Past Ocular History: Myopia Past Medical History: Non-contributory Medications: None Review of Systems: Negative OCULAR EXAMINATION: Visual acuity with correction: • Right (OD): 20/20 • Left (OS): 20/20 Pupils: Briskly reactive without relative afferent pupillary defect Extraocular motility: Full OU Intraocular pressure: 17 mmHg OD, 18 mmHg OS External Exam Right Left External Normal Fullness of superonasal orbit Exophthalmometry 17 mm 18 mm Palpebral Fissure 10 mm 9 mm Margin Reflex Distance 1 4 mm 4 mm with medial ptosis Palpation Within normal limits Superonasal immobile, hard, smooth lesion Slit lamp exam: Normal OU Dilated fundus exam: Normal disc with 0.2 cup to disc ratio and normal macula, vessels and periphery OU Figure 1: External Photograph demonstrating minimal medial ptosis of the left eyelid Figures 2, 3, and 4: Axial and coronal CT images demonstrating the ill-defined hyperosteotic lesion in the superior medial orbit with extension into the ethmoid sinus COURSE: Given the history of recent growth, the decision was made to perform an excisional biopsy of the lesion. -

Things That Go Bump in the Light. the Differential Diagnosis of Posterior

Eye (2002) 16, 325–346 2002 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0950-222X/02 $25.00 www.nature.com/eye IG Rennie Things that go bump THE DUKE ELDER LECTURE 2001 in the light. The differential diagnosis of posterior uveal melanomas Eye (2002) 16, 325–346. doi:10.1038/ The list of lesions that may simulate a sj.eye.6700117 malignant melanoma is extensive; Shields et al4 in a study of 400 patients referred to their service with a pseudomelanoma found these to encompass 40 different conditions at final diagnosis. Naturally, some lesions are Introduction mistaken for melanomas more frequently than The role of the ocular oncologist is two-fold: others. In this study over one quarter of the he must establish the correct diagnosis and patients referred with a diagnosis of a then institute the appropriate therapy, if presumed melanoma were subsequently found required. Prior to the establishment of ocular to have a suspicious naevus. We have recently oncology as a speciality in its own right, the examined the records of patients referred to majority of patients with a uveal melanoma the ocular oncology service in Sheffield with were treated by enucleation. It was recognised the diagnosis of a malignant melanoma. that inaccuracies in diagnosis occurred, but Patients with iris lesions or where the the frequency of these errors was not fully diagnosis of a melanoma was not mentioned appreciated until 1964 when Ferry studied a in the referral letter were excluded. During series of 7877 enucleation specimens. He the period 1985–1999 1154 patients were found that out of 529 eyes clinically diagnosed referred with a presumed melanoma and of as containing a melanoma, 100 harboured a these the diagnosis was confirmed in 936 lesion other than a malignant melanoma.1 cases (81%). -

Enlargement of Choroidal Osteoma in a Child

OCULAR ONCOLOGY ENLARGEMENT OF CHOROIDAL OSTEOMA IN A CHILD A discussion and case report of the diagnosis and management of this rare tumor. BY MARIA PEFKIANAKI, MD, MSC, PHD; KAREEM SIOUFI, MD; AND CAROL L. SHIELDS, MD Choroidal osteoma On ultrasonography, the lesion demonstrated a hyper- is a rare intraocular echoic signal with posterior shadowing suggestive of calcifi- bony tumor that cation. On spectral domain enhanced depth imaging optical typically manifests coherence tomography (EDI-OCT), the mass extended under as a yellow-white, the foveola and there was no evidence of choroidal neovas- well-demarcated cular membrane (CNVM) or subretinal fluid (Figure 2). mass with geographic These features were suggestive of choroidal osteoma with pseudopodal mar- documentation of slow, slight enlargement. Given the pre- gins.1-3 This benign tumor predominantly occurs in the served visual acuity and subfoveal location of the osteoma, we peripapillary or papillomacular region, most often in young elected to observe the lesion. Calcium supplementation was women.1,2 Occasionally, choroidal osteoma can simulate an suggested to maintain calcification of the mass, as decalcifica- amelanotic choroidal tumor such as melanoma, nevus, or tion is a known factor predictive of poor visual outcome.6 metastasis.1,2 This tumor can also simulate choroidal inflam- matory disease such as sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, and other DISCUSSION causes of solitary idiopathic choroiditis.2,4 Due to its calcified Choroidal osteoma is a benign calcified tumor that can nature, -

2018 Solid Tumor Rules Lois Dickie, CTR, Carol Johnson, BS, CTR (Retired), Suzanne Adams, BS, CTR, Serban Negoita, MD, Phd

Solid Tumor Rules Effective with Cases Diagnosed 1/1/2018 and Forward Updated November 2020 Editors: Lois Dickie, CTR, NCI SEER Carol Hahn Johnson, BS, CTR (Retired), Consultant Suzanne Adams, BS, CTR (IMS, Inc.) Serban Negoita, MD, PhD, CTR, NCI SEER Suggested citation: Dickie, L., Johnson, CH., Adams, S., Negoita, S. (November 2020). Solid Tumor Rules. National Cancer Institute, Rockville, MD 20850. Solid Tumor Rules 2018 Preface (Excludes lymphoma and leukemia M9590 – M9992) In Appreciation NCI SEER gratefully acknowledges the dedicated work of Dr. Charles Platz who has been with the project since the inception of the 2007 Multiple Primary and Histology Coding Rules. We appreciate the support he continues to provide for the Solid Tumor Rules. The quality of the Solid Tumor Rules directly relates to his commitment. NCI SEER would also like to acknowledge the Solid Tumor Work Group who provided input on the manual. Their contributions are greatly appreciated. Peggy Adamo, NCI SEER Elizabeth Ramirez, New Mexico/SEER Theresa Anderson, Canada Monika Rivera, New York Mari Carlos, USC/SEER Jennifer Ruhl, NCI SEER Louanne Currence, Missouri Nancy Santos, Connecticut/SEER Frances Ross, Kentucky/SEER Kacey Wigren, Utah/SEER Raymundo Elido, Hawaii/SEER Carolyn Callaghan, Seattle/SEER Jim Hofferkamp, NAACCR Shawky Matta, California/SEER Meichin Hsieh, Louisiana/SEER Mignon Dryden, California/SEER Carol Kruchko, CBTRUS Linda O’Brien, Alaska/SEER Bobbi Matt, Iowa/SEER Mary Brandt, California/SEER Pamela Moats, West Virginia Sarah Manson, CDC Patrick Nicolin, Detroit/SEER Lynda Douglas, CDC Cathy Phillips, Connecticut/SEER Angela Martin, NAACCR Solid Tumor Rules 2 Updated November 2020 Solid Tumor Rules 2018 Preface (Excludes lymphoma and leukemia M9590 – M9992) The 2018 Solid Tumor Rules Lois Dickie, CTR, Carol Johnson, BS, CTR (Retired), Suzanne Adams, BS, CTR, Serban Negoita, MD, PhD Preface The 2007 Multiple Primary and Histology (MPH) Coding Rules have been revised and are now referred to as 2018 Solid Tumor Rules. -

FOS Expression in Osteoid Osteoma and Osteoblastoma

Amary et al FOS Expression in Osteoid Osteoma and Osteoblastoma FOS Expression in Osteoid Osteoma and Osteoblastoma A Valuable Ancillary Diagnostic Tool Fernanda Amary, MD, PhD,*† Eva Markert, MD,* Fitim Berisha, MSc,* Hongtao Ye, PhD,* Craig Gerrand, MD,* Paul Cool, MD,‡ Roberto Tirabosco, MD,* Daniel Lindsay, MD,* Nischalan Pillay, MD, PhD,*† Paul O’Donnell, MD,* Daniel Baumhoer, MD, PhD,§ and Adrienne M. Flanagan, MD, PhD*† light of morphologic, clinical, and radiologic features. Abstract: Osteoblastoma and osteoid osteoma together are the Key Words: bone tumor, osteoblastoma, osteoid osteoma, most frequent benign bone-forming tumor, arbitrarily separated by FOS, c-FOS, immunohistochemistry, FISH, osteosarcoma size. In some instances, it can be difficult to differentiate osteo- blastoma from osteosarcoma. Following our recent description of Osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma together are FOS gene rearrangement in these tumors, the aim of this study is to the most common bone-forming tumors. Arbitrarily evaluate the value of immunohistochemistry in osteoid osteoma, separated by size, osteoid osteoma is defined as measuring osteoblastoma, and osteosarcoma for diagnostic purposes. A total <2 cm diameter, and usually with a classic clinical pre- of 337 cases were tested with antibodies against c-FOS: 84 osteo- sentation of nocturnal pain that is relieved with the use of blastomas, 33 osteoid osteomas, 215 osteosarcomas, and 5 samples non–steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.1,2 Osteoblastoma of reactive new bone formation. In all, 83% of osteoblastomas and is less common than osteoid osteoma and represents 1% of 73% of osteoid osteoma showed significant expression of c-FOS in all benign bone tumors, being by definition 2 cm or more 3,4 the osteoblastic tumor cell component.