Things That Go Bump in the Light. the Differential Diagnosis of Posterior

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clinical Features of Benign Tumors of the External Auditory Canal According to Pathology

Central Annals of Otolaryngology and Rhinology Research Article *Corresponding author Jae-Jun Song, Department of Otorhinolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, Korea University College of Clinical Features of Benign Medicine, 148 Gurodong-ro, Guro-gu, Seoul, 152-703, South Korea, Tel: 82-2-2626-3191; Fax: 82-2-868-0475; Tumors of the External Auditory Email: Submitted: 31 March 2017 Accepted: 20 April 2017 Canal According to Pathology Published: 21 April 2017 ISSN: 2379-948X Jeong-Rok Kim, HwibinIm, Sung Won Chae, and Jae-Jun Song* Copyright Department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Korea University College © 2017 Song et al. of Medicine, South Korea OPEN ACCESS Abstract Keywords Background and Objectives: Benign tumors of the external auditory canal (EAC) • External auditory canal are rare among head and neck tumors. The aim of this study was to analyze the clinical • Benign tumor features of patients who underwent surgery for an EAC mass confirmed as a benign • Surgical excision lesion. • Recurrence • Infection Methods: This retrospective study involved 53 patients with external auditory tumors who received surgical treatment at Korea University, Guro Hospital. Medical records and evaluations over a 10-year period were examined for clinical characteristics and pathologic diagnoses. Results: The most common pathologic diagnoses were nevus (40%), osteoma (13%), and cholesteatoma (13%). Among the five pathologic subgroups based on the origin organ of the tumor, the most prevalent pathologic subgroup was the skin lesion (47%), followed by the epithelial lesion (26%), and the bony lesion (13%). No significant differences were found in recurrence rate, recurrence duration, sex, or affected side between pathologic diagnoses. -

Bone and Soft Tissue Tumors Have Been Treated Separately

EPIDEMIOLOGY z Sarcomas are rare tumors compared to other BONE AND SOFT malignancies: 8,700 new sarcomas in 2001, with TISSUE TUMORS 4,400 deaths. z The incidence of sarcomas is around 3-4/100,000. z Slight male predominance (with some subtypes more common in women). z Majority of soft tissue tumors affect older adults, but important sub-groups occur predominantly or exclusively in children. z Incidence of benign soft tissue tumors not known, but Fabrizio Remotti MD probably outnumber malignant tumors 100:1. BONE AND SOFT TISSUE SOFT TISSUE TUMORS TUMORS z Traditionally bone and soft tissue tumors have been treated separately. z This separation will be maintained in the following presentation. z Soft tissue sarcomas will be treated first and the sarcomas of bone will follow. Nowhere in the picture….. DEFINITION Histological z Soft tissue pathology deals with tumors of the classification connective tissues. of soft tissue z The concept of soft tissue is understood broadly to tumors include non-osseous tumors of extremities, trunk wall, retroperitoneum and mediastinum, and head & neck. z Excluded (with a few exceptions) are organ specific tumors. 1 Histological ETIOLOGY classification of soft tissue tumors tumors z Oncogenic viruses introduce new genomic material in the cell, which encode for oncogenic proteins that disrupt the regulation of cellular proliferation. z Two DNA viruses have been linked to soft tissue sarcomas: – Human herpes virus 8 (HHV8) linked to Kaposi’s sarcoma – Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) linked to subtypes of leiomyosarcoma z In both instances the connection between viral infection and sarcoma is more common in immunosuppressed hosts. -

CASE REPORT Intradermal Nevus of the External Auditory Canal

Int. Adv. Otol. 2009; 5:(3) 401-403 CASE REPORT Intradermal Nevus of the External Auditory Canal: A Case Report Sedat Ozturkcan, Ali Ekber, Riza Dundar, Filiz Gulustan, Demet Etit, Huseyin Katilmis Department of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery ‹zmir Atatürk Research and Training Hospital, Ministry of Health, ‹ZM‹R-TURKEY (SO, AE, FG, DE, HK) Department of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery Etimesgut Military Hospital , ANKARA-TURKEY (RD) Intradermal nevus is the most common skin tumor in humans; however, its occurrence in the external auditory canal (EAC) is uncommon. The clinical manifestations of pigmented nevus of the EAC have been reported to include ear fullness, foreign body sensation, hearing impairment, and otalgia, but some cases were asymptomatic and were found incidentally. The treatment of choice for a symptomatic intradermal nevus in the EAC is complete excision. There has been no recurrence reported in the literature . A pedunculated, papillomatous hair-bearing lesion was detected in the external auditory canal of the patient who was on follow-up for pruritus. Clinical and pathologic features of an intradermal nevus of the external auditory canal are presented, and the literature reviewed. Submitted : 14 October 2008 Revised : 01 July 2009 Accepted : 09 July 2009 Intradermal nevus is the most common skin tumor in left external auditory canal. Otomicroscopic humans; however, its occurrence in the external examination revealed a pedunculated, papillomatous auditory canal (EAC) is uncommon [1-4]. Intradermal hair-bearing lesion in the postero-inferior cartilaginous nevus is considered to be a form of benign cutaneous portion of the external auditory canal (Figure 1). -

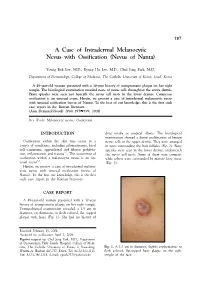

A Case of Intradermal Melanocytic Nevus with Ossification (Nevus of Nanta)

197 A Case of Intradermal Melanocytic Nevus with Ossification (Nevus of Nanta) Young Bok Lee, M.D., Kyung Ho Lee, M.D., Chul Jong Park, M.D. Department of Dermatology, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea A 49-year-old woman presented with a 30-year history of asymptomatic plaque on her right temple. The histological examination revealed nests of nevus cells throughout the entire dermis. Bony spicules were seen just beneath the nevus cell nests in the lower dermis. Cutaneous ossification is an unusual event. Herein, we present a case of intradermal melanocytic nevus with unusual ossification (nevus of Nanta). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first such case report in the Korean literature. (Ann Dermatol (Seoul) 20(4) 197∼199, 2008) Key Words: Melanocytic nevus, Ossification INTRODUCTION drug intake or medical illness. The histological examination showed a dense proliferation of benign Ossification within the skin may occur in a nevus cells in the upper dermis. They were arranged variety of conditions, including pilomatricoma, basal in nests surrounding the hair follicles (Fig. 2). Bony cell carcinoma, appendageal and fibrous prolifera- spicules were seen in the lower dermis, underneath 1,2 tion, inflammation and trauma . The occurrence of the nevus cell nests. Some of them were compact ossification within a melanocytic nevus is an un- while others were surrounded by mature fatty tissue 3-5 usual event . (Fig. 3). Herein, we present a case of intradermal melano- cytic nevus with unusual ossification (nevus of Nanta). To the best our knowledge, this is the first such case report in the Korean literature. -

Short Course 11 Pigmented Lesions of the Skin

Rev Esp Patol 1999; Vol. 32, N~ 3: 447-453 © Prous Science, SA. © Sociedad Espafiola de Anatomfa Patol6gica Short Course 11 © Sociedad Espafiola de Citologia Pigmented lesions of the skin Chairperson F Contreras Spain Ca-chairpersons S McNutt USA and P McKee, USA. Problematic melanocytic nevi melanin pigment is often evident. Frequently, however, the lesion is solely intradermal when it may be confused with a fibrohistiocytic RH. McKee and F.R.C. Path tumor, particularly epithelloid cell fibrous histiocytoma (4). It is typi- cally composed of epitheliold nevus cells with abundant eosinophilic Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, cytoplasm and large, round, to oval vesicular nuclei containing pro- USA. minent eosinophilic nucleoli. Intranuclear cytoplasmic pseudoinclu- sions are common and mitotic figures are occasionally present. The nevus cells which are embedded in a dense, sclerotic connective tis- Whether the diagnosis of any particular nevus is problematic or not sue stroma, usually show maturation with depth. Less frequently the nevus is composed solely of spindle cells which may result in confu- depends upon a variety of factors, including the experience and enthusiasm of the pathologist, the nature of the specimen (shave vs. sion with atrophic fibrous histiocytoma. Desmoplastic nevus can be distinguished from epithelloid fibrous histiocytoma by its paucicellu- punch vs. excisional), the quality of the sections (and their staining), larity, absence of even a focal storiform growth pattern and SiQO pro- the hour of the day or day of the week in addition to the problems relating to the ever-increasing range of histological variants that we tein/HMB 45 expression. -

Eyelid Conjunctival Tumors

EYELID &CONJUNCTIVAL TUMORS PHOTOGRAPHIC ATLAS Dr. Olivier Galatoire Dr. Christine Levy-Gabriel Dr. Mathieu Zmuda EYELID & CONJUNCTIVAL TUMORS 4 EYELID & CONJUNCTIVAL TUMORS Dear readers, All rights of translation, adaptation, or reproduction by any means are reserved in all countries. The reproduction or representation, in whole or in part and by any means, of any of the pages published in the present book without the prior written consent of the publisher, is prohibited and illegal and would constitute an infringement. Only reproductions strictly reserved for the private use of the copier and not intended for collective use, and short analyses and quotations justified by the illustrative or scientific nature of the work in which they are incorporated, are authorized (Law of March 11, 1957 art. 40 and 41 and Criminal Code art. 425). EYELID & CONJUNCTIVAL TUMORS EYELID & CONJUNCTIVAL TUMORS 5 6 EYELID & CONJUNCTIVAL TUMORS Foreword Dr. Serge Morax I am honored to introduce this Photographic Atlas of palpebral and conjunctival tumors,which is the culmination of the close collaboration between Drs. Olivier Galatoire and Mathieu Zmuda of the A. de Rothschild Ophthalmological Foundation and Dr. Christine Levy-Gabriel of the Curie Institute. The subject is now of unquestionable importance and evidently of great interest to Ophthalmologists, whether they are orbital- palpebral specialists or not. Indeed, errors or delays in the diagnosis of tumor pathologies are relatively common and the consequences can be serious in the case of malignant tumors, especially carcinomas. Swift diagnosis and anatomopathological confirmation will lead to a treatment, discussed in multidisciplinary team meetings, ranging from surgery to radiotherapy. -

Lection: Oncology

Lection: Oncology Poltava -2021 • Oncology – branch of science dealing with study of ethiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of tumour. Name comes from word ”oncoma”, which in Greek language means tumour. • A tumor or tumour is the name for a swelling or lesion formed by an abnormal growth of cells (termed neoplastic). • Tumor is not synonymous with cancer. • A tumor can be benign, pre-malignant or malignant, whereas cancer is by definition malignant • Synonyms of the word are blastoma, neoplasm tumour. Tumour • Tumour— this is a self developing pathological formation. Developing in different tissues and organs. • A tumor may be benign, pre-malignant or malignant. The nature of the tumor is determined by a pathologist after examination of the tumor tissues from a biopsy or a surgical excision specimen. Ethiology and pathogenesis • In present time there is not a single theory of arigin of tumour. From the existing theories doctors are attentive to following. 1. Theory of stimulation: given by R.O.Virkhov (1822—1902) according to this theory the mason of existence of cancer is due to long duration of effecting stimulating substance on tissue which leads to the charge of cellular structure and polymorphism of all and their progressive and unlimited growth. 2 .Theory of embryonic origin: given by Kongame (1839—1884) according to this theory tumours arising due to embryonic cells which during the embryonic development did not take part in the formation of organs, not exbased to differentiation i.e. they remained in the facial composition. As a result any mechanical or chemical stimulator effect on them (hey study started reproducing and form tumours. -

Nonpigmented Metastatic Melanoma in a Two-Year-Old Girl: a Serious Diagnostic Dilemma

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Case Reports in Oncological Medicine Volume 2015, Article ID 298273, 3 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/298273 Case Report Nonpigmented Metastatic Melanoma in a Two-Year-Old Girl: A Serious Diagnostic Dilemma Gulden Diniz,1 Hulya Tosun Yildirim,2 Selcen Yamaci,2 and Nur Olgun3 1 Izmir Tepecik Education and Research Hospital, Pathology Laboratory, Turkey 2Izmir Dr. Behcet Uz Children’s Hospital, Pathology Laboratory and Dermatology Clinics, Turkey 3Pediatric Oncology Clinics, Izmir Dokuz Eylul University, Turkey Correspondence should be addressed to Gulden Diniz; [email protected] Received 23 July 2014; Revised 20 January 2015; Accepted 21 January 2015 Academic Editor: Francesca Micci Copyright © 2015 Gulden Diniz et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Although rare, malignant melanoma may occur in children. Childhood melanomas account for only 0.3–3% of all melanomas. In particular the presence of congenital melanocytic nevi is associated with an increased risk of development of melanoma. We herein report a case of malignant melanoma that developed on a giant congenital melanocytic nevus and made a metastasis to the subcutaneous tissue of neck in a two-year-old girl. The patient was hospitalized for differential diagnosis and treatment of cervical mass with a suspicion of hematological malignancy, because the malignant transformation of congenital nevus was not noticed before. In this case, we found out a nonpigmented malignant tumor of pleomorphic cells after the microscopic examination of subcutaneous lesion. -

2. Cancer NOMENCLATURE HYSTOPATHOLOGY-STUDENTS

Why it is important to give the right name to a CANCER disease understanding the pathology and/or histology of CANCER cancer helps you: • to make a correct diagnosis (fundamental Nomenclature - Histopathology step for a correct therapy) • to formulate a better research question (fundamental for studying the etiology, the molecular pathogenesis, and the progression of the disease) • to design novel targeted therapeutic strategies Cancer is not a single static state Neoplasia but a progression and mixture of phenotypic and genetic/epigenetic • Benign tumours : changes that proceed toward – Will remain localized – Cannot (by definition= DOES NOT) spread greater aggressive biological to distant sites behavior – Generally can be locally excised – Patient generally survives Mutation in Mutation in Increasing • Malignant tumours: gene A gene B,C, etc. chromosomal aneuploidy – Can invade and destroy adjacent structure – Can (and OFTEN DOES) spread to distant Normal Cell Increased Benign neoplasia Carcinoma proliferation sites – Cause death (if not treated ) Cancer Hystopathology Diagnosis Neoplasia • Biopsy • two basic components: • Fine-Needle aspiration (FNA) – Parechyma: made up of neoplastic cells • Exfoliative cytology (pap smear) – Stroma: made up of non -neoplastic, • Biochemical markers (PSA, CEA, Alpha- host -derived connective tissue and fetoprotein) blood vessels The parenchyma: The stroma: Determines the Carries the blood biological behavior of the supply tumor Provides support for From which the tumour the growth of the derives its name parenchyma 1. Principle of nomenclature NOMENCLATURE (1) Benign tumors Attaching the suffix “-oma” to the type of cell (glandular, muscular, stromal, etc) The most basic classification plus the organ: e.g., adenoma of thyroid. of human cancer is the More detail: organ or body location in The name of organ and derived tissue/ cell + morphologic character + oma which the cancer arises e. -

Basal Cell Carcinoma Associated with Non-Neoplastic Cutaneous Conditions: a Comprehensive Review

Volume 27 Number 2| February 2021 Dermatology Online Journal || Review 27(2):1 Basal cell carcinoma associated with non-neoplastic cutaneous conditions: a comprehensive review Philip R Cohen MD1,2 Affiliations: 1San Diego Family Dermatology, National City, California, USA, 2Touro University California College of Osteopathic Medicine, Vallejo, California, USA Corresponding Author: Philip R Cohen, 10991 Twinleaf Court, San Diego, CA 92131-3643, Email: [email protected] pathogenesis of BCC is associated with the Abstract hedgehog signaling pathway and mutations in the Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) can be a component of a patched homologue 1 (PCTH-1) transmembrane collision tumor in which the skin cancer is present at tumor-suppressing protein [2-4]. Several potential the same cutaneous site as either a benign tumor or risk factors influence the development of BCC a malignant neoplasm. However, BCC can also concurrently occur at the same skin location as a non- including exposure to ultraviolet radiation, genetic neoplastic cutaneous condition. These include predisposition, genodermatoses, immunosuppression, autoimmune diseases (vitiligo), cutaneous disorders and trauma [5]. (Darier disease), dermal conditions (granuloma Basal cell carcinoma usually presents as an isolated faciale), dermal depositions (amyloid, calcinosis cutis, cutaneous focal mucinosis, osteoma cutis, and tumor on sun-exposed skin [6-9]. However, they can tattoo), dermatitis, miscellaneous conditions occur as collision tumors—referred to as BCC- (rhinophyma, sarcoidal reaction, and varicose veins), associated multiple skin neoplasms at one site scars, surgical sites, systemic diseases (sarcoidosis), (MUSK IN A NEST)—in which either a benign and/or systemic infections (leischmaniasis, leprosy and malignant neoplasm is associated with the BCC at lupus vulgaris), and ulcers. -

A Comparative Study of Oral Hamartoma and Choristoma

Journal of Interdisciplinary Histopathology www.scopmed.org Original Research DOI: 10.5455/jihp.20151020122441 A comparative study of oral hamartoma and choristoma Ilana Kaplan1a, Irit Allon1a, Benjamin Shlomi2, Vadim Raiser2, Dror M. Allon3 1Department of Oral Pathology and Oral ABSTRACT Medicine, School of Dental Aim: To compare the clinical and microscopic characteristics of hamartoma and choristoma of the oral mucosa Medicine, Tel-Aviv, Israel, and jaws and discuss the challenges in diagnosis. Materials and Methods: Analysis of patients diagnosed 2Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, between 2000 and 2012, and literature review of the same years. A sub-classification into “single tissue” Sourasky Medical Center, or “mixed-tissue” types was applied for all the diagnoses according to the histopathological description. Tel-Aviv, Israel, 3Department Results: A total of 61 new cases of hamartoma or choristoma were retrieved, the majority were hamartoma. of Oral and Maxillofacial The literature analysis yielded 155 cases, of which 44.5% were choristoma. The majority of hamartoma were Surgery, Rabin Medical Center, Petach Tiqva, Israel mixed. Among these, neurovascular hamartoma was the most prevalent type (36.7%). Of the choristoma, aThe two authors contributed 59.4% were single tissue, with respiratory, gastric and cartilaginous being the most prevalent single tissue equally to this work types. The tongue was the most frequent location of both groups. Conclusion: Differentiating choristoma from Address of correspondence: hamartoma -

Acral Melanoma

Accepted Date : 07-Jul-2015 Article type : Original Article The BRAAFF checklist: a new dermoscopic algorithm for diagnosing acral melanoma Running head: Dermoscopy of acral melanoma Word count: 3138, Tables: 6, Figures: 6 A. Lallas,1 A. Kyrgidis,1 H. Koga,2 E. Moscarella,1 P. Tschandl,3 Z. Apalla,4 A. Di Stefani,5 D. Ioannides,2 H. Kittler,4 K. Kobayashi,6,7 E. Lazaridou,2 C. Longo,1 A. Phan,8 T. Saida,3 M. Tanaka,6 L. Thomas,8 I. Zalaudek,9 G. Argenziano.10 Article 1. Skin Cancer Unit, Arcispedale Santa Maria Nuova IRCCS, Reggio Emilia, Italy 2. Department of Dermatology, Shinshu University School of Medicine, Matsumoto, Japan 3. Department of Dermatology, Division of General Dermatology, Medical University, Vienna, Austria 4. First Department of Dermatology, Medical School, Aristotle University, Thessaloniki, Greece 5. Division of Dermatology, Complesso Integrato Columbus, Rome, Italy 6. Department of Dermatology, Tokyo Women’s Medical University Medical Center East, Tokyo, Japan 7. Kobayashi Clinic, Tokyo, Japan 8. Department of Dermatology, Claude Bernard - Lyon 1 University, Centre Hospitalier Lyon-Sud, Pierre Bénite, France. 9. Department of Dermatology and Venereology, Medical University, Graz, Austria 10. Dermatology Unit, Second University of Naples, Naples, Italy. This article has been accepted for publication and undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process, which may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record. Please cite this article as Accepted doi: 10.1111/bjd.14045 This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved. Please address all correspondence to: Aimilios Lallas, MD.