Temples, Tombs, Hieroglyphs, History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winter 2004/2005

By Elizabeth Peters In chronological order: Crocodile on the Sandbank Curse of the Pharaohs The Mummy Case MPM Lion in the Valley Deeds of the Disturber The Last Camel Died at Noon a bulletin on the doings and undoings of The Snake, the Crocodile, and the Dog Barbara Mertz/Elizabeth Peters/Barbara Michaels The Hippopotamus Pool Issue 45 Seeing a Large Cat The Ape Who Guards the Balance Winter 2004/2005 The Falcon at the Portal Kristen Whitbread, Editor He Shall Thunder in the Sky Lord of the Silent The Golden One Children of the Storm Guardian of the Horizon The Amelia Peabody Books Serpent on the Crown also look for: mpmbooks.com MPM: Mertz Peters Michaels The official Barbara Mertz/Elizabeth Peters/Barbara Michaels website by Margie Knauff & Lisa Speckhardt PUBLISHING The Serpent on the Crown April 2005 hardcover WilliamMorrow Guardian of the Horizon March 2005 paperback Avon Suspense Children of the Storm April 2004 paperback Avon Suspense The Golden One April 2003 paperback Avon Suspense Amelia Peabody’s Egypt, A Compendium October 2003 hardcover WilliamMorrow Gardening is an exercise in optimism. Sometimes, it is the triumph of hope over experience. Marina Schinz Visions of Paradise MPM For the first time since I bought my camellia Winter Rose, it is blooming its head off. The flowers are smallish, only a couple of inches in diameter, but they are exquisite--shell pink shading to darker in the center. That’s why I love gardening. One might say, if one were pompous (which I am sometimes inclined to be) that it is a metaphor for life: you win some, you lose some, and a good deal of the time you have no idea why. -

Mystery Series 2

Mystery Series 2 Hamilton, Steve 15. Murder Walks the Plank 13. Maggody and the Alex McKnight 16. Death of the Party Moonbeams 1. A Cold Day in Paradise 17. Dead Days of Summer 14. Muletrain to Maggody 2. Winter of the Wolf Moon 18. Death Walked In 15. Malpractice in Maggody 3. The Hunting Wind 19. Dare to Die 16. The Merry Wives of 4. North of Nowhere 20. Laughed ‘til He Died Maggody 5. Blood is the Sky 21. Dead by Midnight Claire Mallory 6. Ice Run 22. Death Comes Silently 1. Strangled Prose 7. A Stolen Season 23. Dead, White, and Blue 2. The Murder at the Murder 8. Misery Bay 24. Death at the Door at the Mimosa Inn 9. Die a Stranger 25. Don’t Go Home 3. Dear Miss Demeanor 10. Let It Burn 26. Walking on My Grave 4. A Really Cute Corpse 11. Dead Man Running Henrie O Series 5. A Diet to Die For Nick Mason 1. Dead Man’s Island 6. Roll Over and Play Dead 1. The Second Life of Nick 2. Scandal in Fair Haven 7. Death by the Light of the Mason 3. Death in Lovers’ Lane Moon 2. Exit Strategy 4. Death in Paradise 8. Poisoned Pins Harris, Charlaine 5. Death on the River Walk 9. Tickled to Death Aurora Teagarden 6. Resort to Murder 10. Busy Bodies 1. Real Murders 7. Set Sail for Murder 11. Closely Akin to Murder 2. A Bone to Pick Henry, Sue 12. A Holly, Jolly Murder 3. Three Bedrooms, One Jessie Arnold 13. -

The Epic Quest Continues in July...@ Your Library Photos from The

Discover What’s New at Your Library Vol. 18 ◊ Issue 4 Jul / Aug 2017 The Epic Quest Continues in July...@ Your Library Summer Reading 2017 July 1st - July 29th Photos from the Newport Aquarium June visit at the Eaton Branch Pictured (L-R): Joseph Armstrong and Clayton Jaros. Photo by Victoria Albaugh, Everyone knows librarians help students find books and other research materials used to write papers, but sometimes they decide to go above and beyond to help those who pass through their library. Joseph Armstrong, a senior in the middle of finals season, needed help to finish his web page design project. He thought he would have to hire an expensive tutor. But Clayton, a children’s librarian at the Eaton Branch who just graduated with a business degree that included a focus on web page design, volunteered his time to help Joseph. They sat down together for a while in the library, and now Joseph is one step closer to completing his project. It’s always wonderful to see our library team going out of their way to help their community. ~Rachel Duncan, Library Assistant, Eaton Branch~ Library Admin. Office 450 S. Barron St. Eaton, OH 45320 (937) 456-4250 www.preblelibrary.org 2 Let’s discover NoveList Plus Emily Hackett, Reference Librarian together! Did you know that the library offers a free readers’ advisory tool that you can use to find that next great read? NoveList Plus is the The Gale Virtual Reference Library has hundreds of titles answer to that age-old question, “What do I read next?” available for your information needs. -

Print This Article

Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections CULTURAL AND RELIGIOUS IMPACTS OF LONG -T ERM CROSS -C ULTURAL MIGRATION BETWEEN EGYPT AND THE LEVANT Thomas Staubli university of fribourg, switzerland ABSTRACT An increase of cross-cultural learning as a consequence of increased travel and migration between Egypt and the Levant during the Iron Age occurred after millennia of migration in earlier times. The result was an Egyptian-Levantine koine, often not recognized as relevant by historians due to an uncritical reproduction of ancient myths of separation. However, the cultural exchange triggered by migration is attested in the language, in the iconography of the region, in the history of the alphabet, in literary motifs, in the characterization of central characters of the Hebrew Bible and, last but not least, in the rise of new religions, which integrated the experience of otherness in a new ethos. Egypt and the Levant: two areas that have countries. in reality, the relations between the eastern continually shaped societies and the advancement of Delta and the Levant were probably, for many centuries, civilization in both the past and the present.” more intense than the relations between the eastern delta “ —Anna-Latifa Mourad (2015, i) and Thebes. in other words, in order to deal seriously with the 1. I NTRODUCTION 1 Levant and northern Egypt as an area of intensive 1.1. T hE ChALLEngE : T hE EsTAbLishED usE of “E gypT ” AnD migration over many millennia and with a focus of the “C AnAAn ” As sEpArATE EnTiTiEs hinDErs ThE rECogniTion effects of this migration on culture, and especially religion, of ThE CrEoLizing EffECTs of MigrATion As highLy rELEvAnT the magic of the biblical Exodus paradigm and its for ThE hisTory of CuLTurEs AnD rELigions in ThE rEgion counterpart, the Egyptian expulsion paradigm, must be The impact of migration on religious development both in removed. -

Women Sleuths 20

Women Sleuths Bibliography Edition 20 January 2020 Brown Deer Public Library 5600 W. Bradley Road Brown Deer, WI 53223 1 MMMysteryMystery Murder Investigation Detective Evidence ClueClue…… She may be a police officer, a private detective, an office worker, a professor, an attorney, a nun, or even a librarian, but the woman sleuth is always tenacious and self-reliant. She may occasionally use her physical strength or a weapon in the course of her crime solving; more often, though, she uses her intelligence, her expertise in a specific area, and her understanding of human nature to reach a solution. The Women Sleuths Bibliography was first compiled by Linda Paulaskas, former South Milwaukee Library Director, and Cathy Morris-Nelson, former Brown Deer Library Director. Kelley Hinton, Reference Librarian at the Brown Deer Library, continued to revise and update the bibliography through the 13th Edition. Since then, updates have been made by Brown Deer Library volunteer and mystery enthusiast Paula Reiter. This is not a comprehensive bibliography, but rather a compilation of current series, which feature a woman sleuth. Most of the titles in this bibliography can be found arranged alphabetically by author at the Brown Deer Public Library. ___ We have added lines in front of each title, so you might keep track of the books and authors you read. We have also included author website addresses and unique features found on the sites. This symbol indicates a series new to the twentieth edition. The cover photo was found on the Paumelia Flickr Creative Commons photostream. Thank you for sharing your photo! Kimura, Yumi. -

Item More Personal, More Unique, And, Therefore More Representative of the Experience of the Book Itself

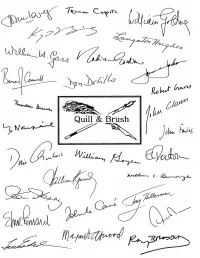

Q&B Quill & Brush (301) 874-3200 Fax: (301)874-0824 E-mail: [email protected] Home Page: http://www.qbbooks.com A dear friend of ours, who is herself an author, once asked, “But why do these people want me to sign their books?” I didn’t have a ready answer, but have reflected on the question ever since. Why Signed Books? Reading is pure pleasure, and we tend to develop affection for the people who bring us such pleasure. Even when we discuss books for a living, or in a book club, or with our spouses or co- workers, reading is still a very personal, solo pursuit. For most collectors, a signature in a book is one way to make a mass-produced item more personal, more unique, and, therefore more representative of the experience of the book itself. Few of us have the opportunity to meet the authors we love face-to-face, but a book signed by an author is often the next best thing—it brings us that much closer to the author, proof positive that they have held it in their own hands. Of course, for others, there is a cost analysis, a running thought-process that goes something like this: “If I’m going to invest in a book, I might as well buy a first edition, and if I’m going to invest in a first edition, I might as well buy a signed copy.” In other words we want the best possible copy—if nothing else, it is at least one way to hedge the bet that the book will go up in value, or, nowadays, retain its value. -

MPM: Mertz . Peters . Michaels

The Amelia Peabody Books By Elizabeth Peters In chronological order: Crocodile on the Sandbank Curse of the Pharaohs MPM The Mummy Case Lion in the Valley Deeds of the Disturber a bulletin on the doings and undoings of The Last Camel Died at Noon Barbara Mertz/Elizabeth Peters/Barbara Michaels The Snake, the Crocodile, and the Dog Issue 41 The Hippopotamus Pool Seeing a Large Cat Winter 2002/2003 The Ape Who Guards the Balance Kristen Whitbread, Editor The Falcon at the Portal He Shall Thunder in the Sky Lord of the Silent The Golden One Children of the Storm also look for: mpmbooks.com MPM: Mertz Peters Michaels The official Barbara Mertz/Elizabeth Peters/Barbara Michaels website by Margie Knauff & Lisa Speckhardt PUBLISHING CHILDREN OF THE STORM April 2003 Hardcover Avon Mystery The Golden One April 2003 paperback Avon Mystery other Elizabeth Peters paperbacks recently (or soon to be) released by Avon Mystery: He Shall Thunder in the Sky April 2002 Legend in Green Velvet September 2002 The Jackal’s Head June 2002 The Night of Four Hundred Rabbits March 2002 Die for Love January 2002 Barbara Michaels paperback released by Harper Torch: Smoke and Mirrors February 2002 I’m a universal patriot, if you could understand me rightly: my country is the world. Charlotte Bronte, The Professor MPM Once again we offer holiday greetings to all people of good will, whatever their beliefs. May they prevail against the forces of violence, war and injustice, here and throughout the world. When you read this, I will be in Egypt again, accompanied by several friends and meeting many oth- ers. -

The Twelfth Dynasty, Whose Capital Was Lisht

استمارة تقييم الرسائل البحثية ملقرر دراس ي اوﻻ : بيانات تمﻷ بمعرفة الطالب اسم الطالب : مصطفى طه علي سليمان كلية : اﻷداب الفرقة/املستوى : اﻷولى الشعبة : شعبة عامة اسم املقرر : English كود املقرر: .. استاذ املقرر : د.آيات الخطيب - د.محمد حامد عمارة البريد اﻻلكترونى للطالب : [email protected] عنوان الرسالة البحثية : The History of the Ancient Egypt ثانيا: بيانات تمﻷ بمعرفة لجنة املمتحنيين هل الرسالة البحثية املقدمة متشابة جزئيا او كليا ☐ نعم ☐ ﻻ فى حالة اﻻجابة بنعم ﻻ يتم تقييم املشروع البحثى ويعتبر غير مجاز تقييم املشروع البحثى م عناصر التقييم الوزن التقييم النسبى 1 الشكل العام للرسالة البحثية 2 تحقق املتطلبات العلمية املطلوبة 3 يذكر املراجع واملصادر العلمية 4 الصياغة اللغوية واسلوب الكتابة جيد نتيجة التقييم النهائى /100 ☐ ناجح ☐ راسب توقيع لجنة التقييم 1. .2 .3 .4 .5 بسم هللا الرمحن الرحي "المقدمة" The history of ancient Egypt spans the period from the early prehistoric settlements of the northern Nile valley to the Roman conquest of Egypt in 30 BC. The pharaonic period, the period in which Egypt was ruled by a pharaoh, is dated from the 32nd century BC, when Upper and Lower Egypt were unified, until the country fell under Macedonian rule in 332 BC. The historical records of ancient Egypt begin with Egypt as a unified state, which occurred sometime around 3150 BC. According to Egyptian tradition, Menes, thought to have unified Upper and Lower Egypt, was the first king. This Egyptian culture, customs, art expression, architecture, and social structure were closely tied to religion, remarkably stable, and changed little over a period of nearly 3000 years. -

ISRAEL in EGYPT This Page Intentionally Left Blank ISRAEL in EGYPT

ISRAEL IN EGYPT This page intentionally left blank ISRAEL IN EGYPT The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Exodus Tradition JAMES K. HOFFMEIER New York Oxford • Oxford University Press Oxford University Press Oxford NewYork Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogota Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris Sao Paulo Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Copyright © 1996 by James K. HofFmeier Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, NewYork, New York 10016 First issued as an Oxford University Press paperback, 1999 Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data HofFmeier, James Karl, 1951- Israel in Egypt : the evidence for the authenticity of the Exodus tradition /James K. HofFmeier p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1SBN-13 978-0-19-509715-3; 978-0-19-513088-1 (pbk.) ISBN 0-19-50971 5-7; 0-19-513088-x (pbk.) I. Exodus, The. 2. Egyptian literature — Relation to the Old Testament. 3. Bible. O.T. Exodus I-XV — Extra-canonical parallels. 1. Title. US680.E9H637 1997 222'. I 2O95 dc2O 96-3 1595 9 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper To Professor Kenneth A. Kitchen on the occasion of his retirement from the University of Liverpool in appreciation for his many yean of friendship, support, and encouragement This page intentionally left blank PREFACE The biblical stories about Israel's origins in Egypt are so well known to people of Europe and the English-speaking world that one hardly has to rehearse the details. -

Print This Article

Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections The Aamu of Shu in the Tomb of Khnumhotep II at Beni Hassan Janice Kamrin American Research Center in Egypt— Cairo A)786(*8 is paper addresses the well- known scene of “Asiatics” in the tomb of Khnumhotep II at Beni Hassan (tomb BH 3), which an associated inscription dates to Year 6 of Senusret II (ca. 1897–1878 bce ). Many scholars have studied this scene and come to a variety of conclusions about the original home of the foreigners represented and the specific reason for their apparent visit to Egypt. ese various theories are dis - cussed and evaluated herein through a detailed review of the scene’s individual elements, along with its accompanying inscriptions. Attention is also paid to the additional levels of meaning embedded in the scene, in which the foreigners function as symbols of controlled and pacified denizens of the chaotic realm that constantly surrounds and threatens the ordered world of the Egyptians. e symbolic levels at which the scene functions within its ritually charged setting neither conflict with nor detract om its historic value, but rather complement and enhance the inherent richness and complexity of the concepts that underlay its creation. he subject of this paper is a well- known image of a group of Amenemhat II and held until at least Year 6 of Senusret II, of foreigners from the tomb of Khnumhotep II at Beni and Mayor ( HAty-a , %¥) in Menat Khufu. 6 As such, it is Hassan (Tomb 3, henceforth BH 3) dating from the thought by some scholars that he would have been in charge of T 1 reign of Senusret II (ca. -

Audio Books on Cassette Tapes Or Cds As of SCN Media Center

SCN Media Center Catalog Audio Books on Cassette Tapes or CDs as of 10/20/2014 (Excludes Music) All Rivers to the Sea Fiction Thoene, Bodie and Brock Audio Book CT 2 3 hrs. 1/1/2000 It is October 1844. As Kate waits for the birth of their baby, Joseph is hiding in London, trying to find a way to come to Ireland and assure himself of his wife's safety. Both plot and counter plot stand between him and a reunion with those he loves. Animal Medicine: Guide to Your Spirit Allies Healing Sams, Jamie Nature Audio Book CT 3 3.5 hr. 1996 These tapes tell about the Native American symbols and spirits in which you find what animal is your power ally. Discover how the animal world can guide you on your path with symbols that have guided the ancient peoples. Blue Shoes and Happiness Botswana Smith, Alexander McCall Botswana Committee Audio Book CD 7 8.25 hr. 2006 Entertainment This is the seventh novel in the phenomenally popular and endlessly charming series that began with the No.1 Ladies Detective Agency. Danger hits close to home when a cobra is found in Mna Ramotsee's office. Bonesetters's Daughter, The Fiction Tan, Amy Audio Book CT 4 6 hr. 2001 The excavation of the Peking Man is being done. This story is an excavation of the human spirit: the past and its wounds and most profound hopes., Page 1 of 7 Children of the Storm Peters, Elizabeth Audio Book CD 5 6 hours 2003 Abridged version performed by Barbara Rosenblat. -

The Merenptah Stele and the Biblical Origins of Israel

JETS 62.3 (2019): 463–93 THE MERENPTAH STELE AND THE BIBLICAL ORIGINS OF ISRAEL LARRY D. BRUCE* Abstract: The Merenptah (or Israel) stele is a fundamental and problematic datum affecting the biblical account of Israel’s origins. The stele contains the first and only accepted reference to Israel in ancient Egyptian records and may suggest the location of Israel before ca. 1209 BC. Virtually all engaged scholars believe the stele intends to locate Israel in Canaan at the time of Pharaoh Merenptah. But the traditional arguments (linguistic and literary) supporting this view may also allow an Israel-in-Egypt interpretation, as this study will attempt to show. A problem with the traditional Israel-in-Canaan interpretation is that it renders the Bible’s ac- count of Israel’s origins in the land of Canaan incoherent and irreconcilable with the archaeo- logical evidence. An Israel-in-Egypt reading, in contrast, presumes an exodus after Meren- ptah’s time (e.g., ca. 1175 BC) resulting in a chronology that aligns or accommodates the bib- lical events and the archaeological evidence at every clearly identified biblical site with data. The books of Genesis and Exodus support the Israel-in-Egypt interpretation. If the post- Merenptah exodus chronology is correct, the Bible’s account of Israel’s origins may be histori- cally accurate in its present form. Key words: Merenptah stele (stela), Israel stele, exodus, conquest, Israel in Canaan, Israel in Egypt, Libyans, Sea People, Ramesses II, Ramesses III, Goshen Sir William Flinders Petrie found a ten-foot-tall black granite slab (a stele or stela) in the ruins of the funerary temple of Pharaoh Merenptah in 1896.1 He dis- covered that the hieroglyphic text on the stele cOntained the first and only known ancient Egyptian reference to the people of Israel.