Print This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Functions and Uses of Egyptian Myth Fonctions Et Usages Du Mythe Égyptien

Revue de l’histoire des religions 4 | 2018 Qu’est-ce qu’un mythe égyptien ? Functions and Uses of Egyptian Myth Fonctions et usages du mythe égyptien Katja Goebs and John Baines Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/rhr/9334 DOI: 10.4000/rhr.9334 ISSN: 2105-2573 Publisher Armand Colin Printed version Date of publication: 1 December 2018 Number of pages: 645-681 ISBN: 978-2-200-93200-8 ISSN: 0035-1423 Electronic reference Katja Goebs and John Baines, “Functions and Uses of Egyptian Myth”, Revue de l’histoire des religions [Online], 4 | 2018, Online since 01 December 2020, connection on 13 January 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/rhr/9334 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/rhr.9334 Tous droits réservés KATJA GOEBS / JOHN BAINES University of Toronto / University of Oxford Functions and Uses of Egyptian Myth* This article discusses functions and uses of myth in ancient Egypt as a contribution to comparative research. Applications of myth are reviewed in order to present a basic general typology of usages: from political, scholarly, ritual, and medical applications, through incorporation in images, to linguistic and literary exploitations. In its range of function and use, Egyptian myth is similar to that of other civilizations, except that written narratives appear to have developed relatively late. The many attested forms and uses underscore its flexibility, which has entailed many interpretations starting with assessments of the Osiris myth reported by Plutarch (2nd century AD). Myths conceptualize, describe, explain, and control the world, and they were adapted to an ever-changing reality. Fonctions et usages du mythe égyptien Cet article discute les fonctions et les usages du mythe en Égypte ancienne dans une perspective comparatiste et passe en revue ses applications, afin de proposer une typologie générale de ses usages – applications politiques, érudites, rituelles et médicales, incorporation dans des images, exploitation linguistique et littéraire. -

New Discoveries in the Tomb of Khety Ii at Asyut*

Originalveröffentlichung in: The Bulletin ofthe Australian Centre for Egyptology 17, 2006, S. 79-95 NEW DISCOVERIES IN THE TOMB OF KHETY II AT ASYUT* Mahmoud El-Khadragy University of Sohag, Egypt Since September 2003, the "Asyut Project", a joint Egyptian-German mission of Sohag University (Egypt), Mainz University (Germany) and Münster University (Germany), has conducted three successive seasons of fieldwork and surveying in the cemetery at Asyut, aiming at documenting the architectural features and decorations of the First Intermediate Period and 1 Middle Kingdom tombs. Düring these seasons, the cliffs bordering the Western Desert were mapped and the geological features studied, providing 2 the clearest picture of the mountain to date (Figure l). In the south and the north, the mountain is cut by small wadis and consists of eleven layers of limestone. Rock tombs were hewn into each layer, but some chronological preferences became obvious: the nomarchs of the First Intermediate Period and the early Middle Kingdom chose layer no. 6 (about two thirds of the way up the mountain) for constructing their tombs, while the nomarchs ofthe 12th Dynasty preferred layer no. 2, nearly at the foot of the gebel. Düring the First Intermediate Period and the Middle Kingdom, stones were quarried in the 3 south ofthe mountain (017.1), thus not violating the necropolis. Düring the New Kingdom, however, stones were hewn from the necropolis of the First Intermediate Period and the Middle Kingdom (Ol5.1), sometimes in the nomarchs' tombs themselves (N12.2, N13.2, see below). 4 5 The tomb of Khety II (Tomb IV; N12.2) is located between the tomb of Iti- ibi (Tomb III; N12.1), his probable father, to the south and that of Khety I 6 (Tomb V; Ml 1.1), which is thought to be the earliest of the three, to the north. -

The Geography and History of Ancient Egypt

05_065440 ch01.qxp 5/31/07 9:20 AM Page 9 Chapter 1 Getting Grounded: The Geography and History of Ancient Egypt In This Chapter ᮣ Exploring the landscape of Egypt ᮣ Unifying the two lands ᮣ Examining the hierarchy of Egyptian society he ancient Egyptians have gripped the imagination for centuries. Ever since TEgyptologists deciphered hieroglyphs in the early 19th century, this won- derful civilisation has been opened to historians, archaeologists, and curious laypeople. Information abounds about the ancient Egyptians, including fascinating facts on virtually every aspect of their lives – everything from the role of women, sexuality, and cosmetics, to fishing, hunting, and warfare. The lives of the ancient Egyptians can easily be categorised and pigeonholed. Like any good historian, you need to view the civilisation as a whole, and the best starting point is the origin of these amazing people. So who were the ancient Egyptians? Where did they come from? This chapter answers these questions and begins to paint a picture of the intricately organ- ised culture that developed, flourished, and finally fell along the banks of the Nile river.COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL Splashing in the Source of Life: The Nile The ancient Egyptian civilisation would never have developed if it weren’t for the Nile. The Nile was – and still is – the only source of water in this region of north Africa. Without it, no life could be supported. 05_065440 ch01.qxp 5/31/07 9:20 AM Page 10 10 Part I: Introducing the Ancient Egyptians Ancient Egypt is often called the Nile valley. This collective term refers to the fertile land situated along the banks of the river, covering an area of 34,000 square kilometres. -

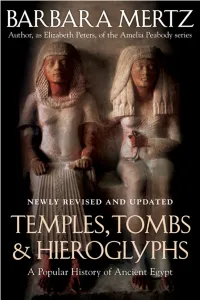

Temples, Tombs, Hieroglyphs, History

TEMPLES, TOMBS & HIEROGLYPHS A Popular History of Ancient Egypt SECOND EDITION Barbara Mertz To John A. Wilson 1899–1976 Scholar, teacher, humanist Contents Foreword to the First Edition vii Foreword to the Second Edition xi A Note on Names xiii Ancient Egyptian Chronology xv List of Black-and-White Illustrations xix List of Color Illustrations in Photograph Insert xxi List of Maps xxiii one: The Two Lands 1 Geb the Hunter 1 The Wagon or the Mountain 16 iv contents Troubles with Time 24 Wearers of the Double Crown 33 Wars of Religion? 41 two: Houses of Eternity 46 King Djoser’s Magician 46 Good King Snefru 54 The Missing Queen 64 Children of Re 75 three: The Good Shepherd 95 Despair and Deliverance 95 Binder of the Two Lands 107 four: The Fight for Freedom 126 Invasion 126 Liberation 132 five: The Woman Who Was king 142 Hatshepsut the Queen 142 The King of Upper and Lower Egypt 145 The Hatshepsut Problem 162 The Other Hatshepsut Problem 164 Photographic Insert six: The Conqueror 168 contents v seven: The Power and The Glory 190 Amenhotep II 190 Amenhotep the Magnificent 198 eight: The Great Heresy 205 nine: The Broken Reed 240 Look on My Works! 240 Ramses II 244 Peoples of the Sea 257 ten: The Long Dying 269 Adventures of a Man of No Consequence 269 The Quick and the Dead 274 Tomb Robbers and Royal Mummies 277 Mummy Musical Chairs 282 The Third Intermediate Period 283 Horse men from the Holy Mountain 286 Back to the Drawing Board 295 The Final Humiliation 299 Additional Reading 309 Sources of Quotes 313 Index 315 About the Author Other Books by Barbara Mertz Credits Cover Copyright About the Publisher Foreword to the First Edition My affaire de coeur with ancient Egypt began in remote childhood, when I first encountered James Henry Breasted’s History of Egypt at the local li- brary; it is still flourishing, although many years and many distractions have intervened. -

Hatshepsut: Pharaoh of Egypt

in fact a woman. Hatshepsut was the sixth pharaoh of ancient Egypt’s eighteenth dynasty, during the time called the New Kingdom period. Ancient Egypt’s New Kingdom lasted from 1570 until 1069 B.C.E. Some Hatshepsut: Pharaoh of the best-known pharaohs ruled during this time, including Thutmose, of Egypt Amenhotep, Akhenaten, and Tutankha- mun. However, the name Hatshepsut Although the pyramids of ancient remained largely unknown for thou- Egypt have existed for thousands of sands of years. years, the study of ancient Egypt, called Hatshepsut ruled Egypt from 1473 Egyptology, began in earnest in the until 1458 B.C.E. While she is not the early 1800s. At this time, people had fi- only woman to have ever served as pha- nally learned how to read hieroglyphics, raoh, no woman ruled longer. Today, the ancient Egyptian system of pictorial most historians agree that Hatshepsut writing. Once scholars could read hi- was the most powerful and successful eroglyphics, they were able to increase female pharaoh. their knowledge of ancient Egyptian cul- Historians are unsure of Hatshepsut’s ture and history. actual birthdate. They do know that she In 1822, when reading the text in- was the oldest of two daughters born to scribed on an ancient monument, Egyp- the Egyptian king Thutmose I and to his tologists encountered a puzzling figure. queen, Ahmes. Thutmose I was a charis- This person was a pharaoh of Egypt. matic ruler and a powerful military lead- Like other Egyptian rulers, this pha- er. Hatshepsut was married to her half raoh was depicted, or shown, wearing brother, Thutmose II. -

The Season's Work at Ahnas and Beni Hasan : 1890-1891

NYU IFA LIBRARY 3 1162 04538879 1 The Stephen Chan Library of Fine Arts NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES A private university in the public service INSTITUTE OF FINE ARTS /^ pn h 1^ liMt^itAiMfeiii a ^ D a D D D [1 D <c:i SLJ Ua iTi ^2^ EGYPT EXPLORATION FUND SPECIAL EXTBA BEPOBT THE SEASON'vS WORK AHNAS AND BENI HASAN CONTAIXING THE REPORTS OF M. NAVILLE, Mr. PERCY E. NEWBERRT AXIi Mr. ERASER (WITH SEVEN ILLUSTRATIONS) 1890—1891 FUBLISHED BY GILBERT k RIVIXGTON, Limited ST. JOHN'S HOUSE, CLERKENWELL, LONDON, E.G. ANll SOLr> AT TUE OFFICES OF THE EGYPT EXPLORATION FUND 17, Oxford JIan-siox, Oxford Circus, Loxnox, W. 181»1 J'ri'-i' Tirii Slullini/.-: au'J Sij-iniic- The Stephen Chan Library of Fine Arts NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES A private university in t/ie public service INSTITUTE OF FINE ARTS /d ilt^^^kftjMI IWMbftjfeJt^ll D D D ODD a a i THE SEASON'S WOEK AHNAS AND BENI HASAN. SPECIAL EXTEA EEPOET THE SEASON'S WOEK AT AHNAS AND BENI HASAN CONTAINIXG REPOETS BY M. NAVILLE, Mk. PERCY E. NEWBERRY 'I AND Me. GEORGE WILLOUGHBY ERASER WITH AN EISTOEICAL INTEODUCTION 1890—1891 PUBLISHED BY GILBEKT & EIVINGTON, LiiiiTED ST. JOHN'S HOUSE, CLERKENWELL, LONDON, E.G. AND SOLD AT THE OFFICES OF THE EGYPT EXPLORATION FUND 17, OxFOSD Mansion, Oxford Circus, London, W. 1891 TSStWm OF nSK EMS rew tOM. ONIVERSITT 7)7 A/ 3^ CONTENTS. Secretary 1 Introduction . Amelia B. Edwards, Honorary I. Excavations at Henassieh (Hanes) . Edouard Naville 5 II. The Tombs of Beni Hasan . -

Bulletin De L'institut Français D'archéologie

MINISTÈRE DE L'ÉDUCATION NATIONALE, DE L'ENSEIGNEMENT SUPÉRIEUR ET DE LA RECHERCHE BULLETIN DE L’INSTITUT FRANÇAIS D’ARCHÉOLOGIE ORIENTALE en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne BIFAO 117 (2017), p. 293-317 Aurore Motte Reden und Rufe, a Neglected Genre? Towards a Definition of the Speech Captions in Private Tombs Conditions d’utilisation L’utilisation du contenu de ce site est limitée à un usage personnel et non commercial. Toute autre utilisation du site et de son contenu est soumise à une autorisation préalable de l’éditeur (contact AT ifao.egnet.net). Le copyright est conservé par l’éditeur (Ifao). Conditions of Use You may use content in this website only for your personal, noncommercial use. Any further use of this website and its content is forbidden, unless you have obtained prior permission from the publisher (contact AT ifao.egnet.net). The copyright is retained by the publisher (Ifao). Dernières publications 9782724708288 BIFAO 121 9782724708424 Bulletin archéologique des Écoles françaises à l'étranger (BAEFE) 9782724707878 Questionner le sphinx Philippe Collombert (éd.), Laurent Coulon (éd.), Ivan Guermeur (éd.), Christophe Thiers (éd.) 9782724708295 Bulletin de liaison de la céramique égyptienne 30 Sylvie Marchand (éd.) 9782724708356 Dendara. La Porte d'Horus Sylvie Cauville 9782724707953 Dendara. La Porte d’Horus Sylvie Cauville 9782724708394 Dendara. La Porte d'Hathor Sylvie Cauville 9782724708011 MIDEO 36 Emmanuel Pisani (éd.), Dennis Halft (éd.) © Institut français d’archéologie orientale - Le Caire Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) 1 / 1 Reden und Rufe, a Neglected Genre? Towards a Definition of the Speech Captions in Private Tombs aurore motte* introduction Within the scope of my PhD research, I investigated a neglected corpus in Egyptology: the speech captions found in “daily life” scenes in private tombs. -

Pharaohs in Egypt Fathi Habashi

Laval University From the SelectedWorks of Fathi Habashi July, 2019 Pharaohs in Egypt Fathi Habashi Available at: https://works.bepress.com/fathi_habashi/416/ Pharaohs of Egypt Introduction Pharaohs were the mighty political and religious leaders who reigned over ancient Egypt for more than 3,000 years. Also known as the god-kings of ancient Egypt, made the laws, and owned all the land. Warfare was an important part of their rule. In accordance to their status as gods on earth, the Pharaohs built monuments and temples in honor of themselves and the gods of the land. Egypt was conquered by the Kingdom of Kush in 656 BC, whose rulers adopted the pharaonic titles. Following the Kushite conquest, Egypt would first see another period of independent native rule before being conquered by the Persian Empire, whose rulers also adopted the title of Pharaoh. Persian rule over Egypt came to an end through the conquests of Alexander the Great in 332 BC, after which it was ruled by the Hellenic Pharaohs of the Ptolemaic Dynasty. They also built temples such as the one at Edfu and Dendara. Their rule, and the independence of Egypt, came to an end when Egypt became a province of Rome in 30 BC. The Pharaohs who ruled Egypt are large in number - - here is a selection. Narmer King Narmer is believed to be the same person as Menes around 3100 BC. He unified Upper and Lower Egypt and combined the crown of Lower Egypt with that of Upper Egypt. Narmer or Mena with the crown of Lower Egypt The crown of Lower Egypt Narmer combined crown of Upper and Lower Egypt Djeser Djeser of the third dynasty around 2670 BC commissioned the first Step Pyramid in Saqqara created by chief architect and scribe Imhotep. -

History Nov 14 Early NK.Pdf

What are themes of the early 18th Dynasty? What should we look for when approaching reigns? How are kings and kingship defined in the early 18th Dynasty? What is the military position of Egypt in the early 18th Dynasty? Luxor How are the gods accommodated in Temple the early 18th Dynasty? Karnak Temple Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple What is the relationship at Deir el-Bahri between kingship and divinity in the early 18th Dynasty? What roles do royal women play in the early 18th Dynasty? Themes for studying 18th Dynasty: Kingship: builder, warrior, connected to divine Military: creation and maitenance of empire Religion: temples as major recipients of both the building impulse and the loot of war; become part and parcel of the refinement of the definition of kingship Royal women: individual women, offices held by women Non-royal part of the equation: government and the relations between bureaucrats and royalty; religious role of private individuals Genealogy of the early 18th Dynasty 17th Dynasty (Second Intermediate Period) 18th Dynasty (New Kingdom) = Red indicates people who ruled as kings Royal women in Ahmose’s reign: The ancestors Burial of Ahhotep by Stela for Tetisheri erected by Ahmose (her son) Ahmose (her grandson) at Abydos Ahmose-Nefertari, wife of Ahmose First “God’s Wife of Amun” More from Ahmose son of Abana from the reign of Ahmose “Now when his majesty had slain the nomads of Asia, he sailed south to Khent-hen-nefer, to destroy the Nubian Bowmen. His majesty made a great slaughter among them, and I brought spoil from there: two living men and three hands. -

Last Chance – Webinar – Hatshepsut 1 October 2020

MMA 29.3.3 MMA 29.3.3 F 1928/9.2 Leiden Oudheden Rijksmuseum van JE 53113 Cairo Last Chance – Webinar – Hatshepsut 1 October 2020 Dr Susanne Binder susanne.binder@ mq.edu.au Head of statue of Hatshepsut Frontispiece Catherine H. Roehrig, Hatshepsut from Queen to Pharaoh, New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005. When thinking about the difference between art and life, consider this ... examples of royal portraiture 1 2 3 Hatshesut as pharaoh – can you put these statues into chronological order? MMA 29.3.3 + Rijksmuseum van Oudheden Leiden F 1928/9.2 (cat. no. 95) | MMA 29.3.2 (cat. no.96) |striding statue: MMA 28.3.18 (cat. no. 94) Checklist – primary sources – primary data line up your facts personality Hatshepsut title “from queen to pharaoh” free download https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/Hat shepsut_From_Queen_to_Pharaoh Checklist – primary sources – primary data line up your facts personality Hatshepsut when ? family: parents marriage – children important life events “from queen to pharaoh” building program developments in politics /society international relations: Egypt and its neighbours Who is who? contemporaries /society burial place human remains free download https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/Hat shepsut_From_Queen_to_Pharaoh New Kingdom 1550 BCE Family Thutmosis I circa 1504-1492 BCE Hatshepsut circa 1473-1458 BCE father – mother Tuthmosis I Ahmose MMA 29.3.2 From the reliefs of Deir el Bahari Queen Ahmose water colour facsimile : Deir el Bahari Howard Carter Brooklyn 57.76.2 Roehrig, Hatshepsut from -

Egyptian Long-Distance Trade in the Middle Kingdom and the Evidence at the Red Sea Harbour at Mersa/Wadi Gawasis

Egyptian Long-Distance Trade in the Middle Kingdom and the Evidence at the Red Sea Harbour at Mersa/Wadi Gawasis Kathryn Bard Boston University Rodolfo Fattovich University of Naples l’Orientale Long-distance Trade in the Middle Kingdom After a period of breakdown of the centralized state in the late third millen- nium BC (the First Intermediate Period), Egypt was reunified as a result of war- fare. The victors of this warfare were kings of the later 11th Dynasty, whose power base was in the south, in Thebes. Known as the Middle Kingdom, this reunified state consolidated in the 12th Dynasty. The accomplishments of this dynasty are many, including a number of seafaring expeditions sent to the Southern Red Sea region from the harbor of Saww at Mersa/Wadi Gawasis. In the Early Middle Kingdom the reunified Egyptian state began to expand its activities outside the Nile Valley and abroad, especially for the exploitation and/or trade of raw materials used to make elite artifacts and tools, as well as timbers with which to build boats—all not available in Egypt. Copper and turquoise mines were actively exploited by expeditions in Southwestern Sinai, where extensive mines date to the Middle and New Kingdoms (Kemp 2006: 141–142; O’Connor 2006: 226). Cedar was imported in large quantities from Lebanon, and was used to make coffins for high status officials (Berman 2009), as well as to build seafaring ships that have been excavated at Egypt’s harbor on the Red Sea at Mersa/Wadi Gawasis (Bard and Fattovich 2007, 2010, 2012). -

Ritual Marriage Alliances and Consolidation of Power in Middle Egypt During the Middle Kingdom

Études et Travaux XXX (2017), 267–288 Ritual Marriage Alliances and Consolidation of Power in Middle Egypt during the Middle Kingdom N K Abstract: Middle Egypt is the most fertile region in the country and its provincial gover- nors were the richest and most powerful. Intermarriages between members of neighbouring nomarchic families created a strong power base, resulting in most governors gradually representing themselves in such forms and using formulae which are strictly royal. While there is no evidence that any of the governors actually challenged the authority of the king, it seems doubtful if the latter would have been pleased with the grand claims made by some of his top administrators and the royal prerogatives they attributed to themselves. The almost simultaneous end of Middle Kingdom nobility in diff erent provinces, under Senwosret III, even though presumably not everywhere at exactly the same time, appears to have been the result of a planned central policy, although each province was dealt with diff erently and as the opportunity presented itself. Keywords: Middle Kingdom Egypt, Twelfth Dynasty, provincial administration, marriage and politics, crown and offi cials, usurpation of power Naguib Kanawati, Australian Centre for Egyptology, Macquarie University, Sydney; [email protected] According to two studies conducted by the Egyptian Ministry of Agriculture, Middle Egypt, or broadly the area between nomes 9 and 20, is the most fertile and most productive land in the country,1 and we have no reason to believe that conditions were diff erent in the Middle Kingdom. The wealth of the region in ancient times may be gauged by the richness of the tombs of its provincial governors, particularly those of Asyut, Meir, el-Bersha and Beni Hassan.