A Prisoner's Conviction: Time, Space, and Morality in W.F. Hermans's The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View List (.Pdf)

Symphony Society of New York Stadium Concert United States Premieres New York Philharmonic Commission as of November 30, 2020 NY PHIL Biennial Members of / musicians from the New York Philharmonic Click to jump to decade 1842-49 | 1850-59 | 1860-69 | 1870-79 | 1880-89 | 1890-99 | 1900-09 | 1910-19 | 1920-29 | 1930-39 1940-49 | 1950-59 | 1960-69 | 1970-79 | 1980-89 | 1990-99 | 2000-09 | 2010-19 | 2020 Composer Work Date Conductor 1842 – 1849 Beethoven Symphony No. 3, Sinfonia Eroica 18-Feb 1843 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 7 18-Nov 1843 Hill Vieuxtemps Fantasia pour le Violon sur la quatrième corde 18-May 1844 Alpers Lindpaintner War Jubilee Overture 16-Nov 1844 Loder Mendelssohn The Hebrides Overture (Fingal's Cave) 16-Nov 1844 Loder Beethoven Symphony No. 8 16-Nov 1844 Loder Bennett Die Najaden (The Naiades) 1-Mar 1845 Wiegers Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3, Scottish 22-Nov 1845 Loder Mendelssohn Piano Concerto No. 1 17-Jan 1846 Hill Kalliwoda Symphony No. 1 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Furstenau Flute Concerto No. 5 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Donizetti "Tutto or Morte" from Faliero 20-May 1846 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 9, Choral 20-May 1846 Loder Gade Grand Symphony 2-Dec 1848 Loder Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld Beethoven Symphony No. 4 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld 1850 – 1859 Schubert Symphony in C major, Great 11-Jan 1851 Eisfeld R. Schumann Introduction and Allegro appassionato for Piano and 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld Orchestra Litolff Chant des belges 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld R. Schumann Overture to the Incidental Music to Byron's Dramatic 21-Nov 1857 Eisfeld Poem, Manfred 1860 - 1869 Brahms Serenade No. -

QNF V5 Proef 4.1 2

no. 5 spring 2001 QUALITY NON-FICTION FROM HOLLAND FOUNDATION FOR THE PRODUCTION Special Issue: AND TRANSLATION OF DUTCH th LITERATURE 20 Century Classics Singel 464 nl6-61017 aw2Amsterdam contained brief biographical sketches of more than 150 tel+631 206620662661 fifteenth and sixteenth-century Dutch and Flemish painters. Three quarters of a century later there fol- fax 6 6 6 6 + 31 20 620 71 79 lowed a most original book by Rembrandt’s pupil [email protected] Samuel van Hoogstraeten, the Inleyding tot de Hooge website www.nlpvf.nl Schoole der Schilderkonst (Introduction to the High School of Painting; 1678). Arnold Houbraken’s De groote schouwburgh der Nederlantsche konstschilders en schilderessen (The Great Theatre of Dutch Painters; 1718- 1721) was a sequel to Mander’s book, as entertaining as Which tradition can be said to lie at the root of the it was informative. With his account of nearly a thou- books we have been presenting as the best Netherlands sand Dutch painters of both sexes he set the tone for non-fiction over the past four years? Everyone knows generations of art collectors. A modern classic in the the historian Johan Huizinga who achieved world history of Dutch art, finally, is Bob Haak’s Hollandse renown with his The Waning of the Middle Ages (1919), schilders in de Gouden Eeuw (Dutch Painters in the but even Huizinga had important predecessors. Golden Age; 1984), a lavishly illustrated book by a lead- From the end of the sixteenth century, Dutchmen could ing connoisseur. be found crossing the oceans. Their travel books con- Erasmus and Spinoza, the most important philosophers veyed a vivid picture of the life of seafarers, but above the Netherlands has produced, admittedly wrote in all they had a lasting influence on the European view of Latin, but left an indelible impression on Dutch litera- the outside world. -

The Development of Free Indirect Constructions in Dutch Novels

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2014 The development of free indirect constructions in Dutch novels Clement, Marja Abstract: Why is the free indirect style such a useful narrative means to portray characters’ minds in fictional texts? This article gives more insight into this phenomenon by analyzing texts fromearlier times. Previous studies state that the free indirect style for the representation of thoughts emerged in Dutch literary prose in the 19th century. However, this article shows that the roots of this technique were already present in 17th century Dutch popular literature novels. The analysis of these novels provides us with more insight into this phenomenon. Before the emergence of free indirect style, the most common form for the representation of a character’s consciousness was direct discourse. The suggestion that the character is ‘thinking out loud’ makes this thought representation unnatural, as emotions and feelings are often pre-verbal and wordless. Free indirect style gives the narrator the possibility to formulate that which the character cannot put into words. The free indirect style allows the author to merge descriptions of events and actions with the character’s inner life, feelings, questions and wishes without a change in the narrative style when it comes to personal pronouns and tense. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/jls-2014-0009 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-105884 Journal Article Published Version Originally published at: Clement, Marja (2014). -

This Cannot Happen Here Studies of the Niod Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies

This Cannot Happen Here studies of the niod institute for war, holocaust and genocide studies This niod series covers peer reviewed studies on war, holocaust and genocide in twentieth century societies, covering a broad range of historical approaches including social, economic, political, diplomatic, intellectual and cultural, and focusing on war, mass violence, anti- Semitism, fascism, colonialism, racism, transitional regimes and the legacy and memory of war and crises. board of editors: Madelon de Keizer Conny Kristel Peter Romijn i Ralf Futselaar — Lard, Lice and Longevity. The standard of living in occupied Denmark and the Netherlands 1940-1945 isbn 978 90 5260 253 0 2 Martijn Eickhoff (translated by Peter Mason) — In the Name of Science? P.J.W. Debye and his career in Nazi Germany isbn 978 90 5260 327 8 3 Johan den Hertog & Samuël Kruizinga (eds.) — Caught in the Middle. Neutrals, neutrality, and the First World War isbn 978 90 5260 370 4 4 Jolande Withuis, Annet Mooij (eds.) — The Politics of War Trauma. The aftermath of World War ii in eleven European countries isbn 978 90 5260 371 1 5 Peter Romijn, Giles Scott-Smith, Joes Segal (eds.) — Divided Dreamworlds? The Cultural Cold War in East and West isbn 978 90 8964 436 7 6 Ben Braber — This Cannot Happen Here. Integration and Jewish Resistance in the Netherlands, 1940-1945 isbn 978 90 8964 483 8 This Cannot Happen Here Integration and Jewish Resistance in the Netherlands, 1940-1945 Ben Braber Amsterdam University Press 2013 This book is published in print and online through the online oapen library (www.oapen.org) oapen (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) is a collaborative initiative to develop and implement a sustainable Open Access publication model for academic books in the Humanities and Social Sciences. -

Almost Memories / Almost True Stories

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Flinders Academic Commons Cees Nooteboom, The Foxes Come at Night translated from Dutch by Ina Rilke (Quercus, 2011) Cees Nooteboom belongs to a generation of Dutch writers who were born before the war and with the death earlier this year of Harry Mulisch (The Discovery of Heaven, 1982) Nooteboom is one of the last alive. Unlike Mulisch who wrote relentlessly about the post-war Dutch landscape and whose work is thus closer to Gunther Grass in Germany, Nooteboom is more identifiable with writers such as the much younger Ian Buruma (Murder in Amsterdam, 2006) who, if they write about the Netherlands at all, do so from an outsider/expatriate viewpoint. Like Buruma, Nooteboom is an analytical essayist with an extensive oeuvre of travel writing and commentary about the arts. Nooteboom is unique however in that he is an experimenter and thus is not easily classifiable at all. In The Foxes Come at Night he pushes the boundaries of what we think of as the short story genre to the furthest edges of his imagination. Something else to keep in mind in any consideration of Nooteboom is that his father died in an Allied bombing raid during the war. He has known tragic, inexplicable death from an early age and, like Proust who came to realise that he was the subject of his writing, there is a sense that Nooteboom is studying himself in these stories. A melancholy, the black bile of ancient Greece, pervades all of Nooteboom’s work, an attraction to decay, ennui – the end of things. -

ACF Regionals 2020 Packet O by the Editors Edited by Jinah Kim, Jordan

ACF Regionals 2020 Packet O by the Editors Edited by JinAh Kim, Jordan Brownstein, Geoffrey Chen, Taylor Harvey, Wonyoung Jang, Nick Jensen, Dennis Loo, Nitin Rao, and Neil Vinjamuri, with contributions from Billy Busse, Ophir Lifshitz, Tejas Raje, and Ryan Rosenberg Tossups 1. Voters in this state wrote “No Dams” on their ballot paper as part of a campaign to block the construction of the Franklin Dam. The flooding of this state’s Lake Pedder led to the formation of a “United Group” named for this state that became the world’s first green party. George Augustus Robinson arrived in this colony to “conciliate” a conflict between colonists and an indigenous group whose last surviving member was Truganini. This colony’s governor George Arthur ordered the formation of a human cordon to round up its indigenous inhabitants. John Howard instituted a mandatory buyback policy on long guns after 35 people died in this state’s Port Arthur Massacre. For 10 points, the Black War exterminated the aboriginal inhabitants of what Australian island? ANSWER: Tasmania <European History> 2. Schlenk and Brauns name a group of these molecules that exist as biradicals and are paramagnetic with a triplet ground state. The F number is correlated to the log of the retention factor in chromatography of these molecules. Clar’s rule is used to determine the most stable forms of these molecules. A process in which these molecules are broken down uses a system consisting of an alumina matrix, a silica binder, a kaolin filler, and a zeolite catalyst; that process is fluid catalytic cracking. -

Coming to Terms with the Past and Searching for an Identity: the Treatment of the Occupied Netherlands 179 Brother Alqng with Qther Hqstages

178 JOHN MICHIELSEN, BROCK UNIVERSITY i • I ; Coming to Terms With the Past and Searching for an Identity: II The Treatment of The Occupied Netherlands in the Fi<;tion of Hermans, Mulisch and Vestdijk / The popularity of Harry Mulisch's De had been somewhere else at a certain time aanslag, which was published in September things would have worked out differently. 1982, shows the constant interest that the This is especially the case in De aanslag and Dutch have had in literature dealing with the De donkere kamer. Pastorale 1943 concerns occupation of the Netherlands during World itself less with this question, perhaps because War Two. Simon Vestdijk's Pastorale 1943, it was written during and immediately after published in 1946, and Willem Frederik the occupation and its author's stay in prison. Hermans' De donkere kamer van Damokles of Vestdijk wished to render a vivid and realistic 1958 also deal with the same period. The three description of the lives of those who novels are interesting as a picture of the time; collaborated with the Germans, those who they concern themselves in part with the role worked for the underground, and those who of the resistance during the occupation and were hiding from the Germans. Even here, also the relationship between the occupied however, chance plays a role in what happens Dutch and the enemy. Naturally, the question to the characters. of guilt, both of the Germans and their collaborators the Dutch Nazis, arises in this As far as the structure of the novels is context. The three novels also present the concerned, De aanslag and De donkere kamer thesis that groups working against the enemy are the more complex novels of the three and were composed of bungling dilettantes, they are also the richest in symbols. -

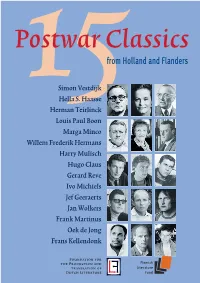

From Holland and Flanders

Postwar Classics from Holland and Flanders Simon Vestdijk 15Hella S. Haasse Herman Teirlinck Louis Paul Boon Marga Minco Willem Frederik Hermans Harry Mulisch Hugo Claus Gerard Reve Ivo Michiels Jef Geeraerts Jan Wolkers Frank Martinus Oek de Jong Frans Kellendonk Foundation for the Production and Translation of Dutch Literature 2 Tragedy of errors Simon Vestdijk Ivory Watchmen n Ivory Watchmen Simon Vestdijk chronicles the down- I2fall of a gifted secondary school student called Philip Corvage. The boy6–6who lives with an uncle who bullies and humiliates him6–6is popular among his teachers and fellow photo Collection Letterkundig Museum students, writes poems which show true promise, and delights in delivering fantastic monologues sprinkled with Simon Vestdijk (1898-1971) is regarded as one of the greatest Latin quotations. Dutch writers of the twentieth century. He attended But this ill-starred prodigy has a defect: the inside of his medical school but in 1932 he gave up medicine in favour of mouth is a disaster area, consisting of stumps of teeth and literature, going on to produce no fewer than 52 novels, as the jagged remains of molars, separated by gaps. In the end, well as poetry, essays on music and literature, and several this leads to the boy’s downfall, which is recounted almost works on philosophy. He is remembered mainly for his casually. It starts with a new teacher’s reference to a ‘mouth psychological, autobiographical and historical novels, a full of tombstones’ and ends with his drowning when the number of which6–6Terug tot Ina Damman (‘Back to Ina jealous husband of his uncle’s housekeeper pushes him into Damman’, 1934), De koperen tuin (The Garden where the a canal. -

Willem Frederik Hermans Het Behouden Huis (1951)

Willem Frederik Hermans (1921-1995) Het behouden huis (1951) Vragen en opdrachten Inhoud Willem Frederik Hermans (1921-1995) 3 Het behouden huis (1951) 5 De Grote Drie (Hermans, Reve en Mulisch) 7 Vragen en opdrachten 10 Verder lezen 13 Bronnen 14 2 Willem Frederik Hermans (1921-1995) Willem Frederik Hermans werd in 1921 geboren in Amsterdam in een onderwijzersgezin. Aan het begin van de oorlog pleegde zijn zus zelfmoord; dat was een grote schok voor Hermans. Na het afronden van het gymnasium ging hij fysische geografie studeren. Hij promoveerde cum laude in 1955 en werkte tot 1973 aan de universiteit van Groningen. Daarna ging hij in Parijs en later nog in Brussel wonen. Hermans schreef romans, verhalen, gedichten, toneelstukken en essays. Zijn bekendste boeken zijn De donkere kamer van Damokles (1958) en Nooit meer slapen (1966). In 1947 verscheen zijn debuutroman De tranen der acacia’s en vele lezers vonden het een schokkend boek. In de personages van dit boek zag men een door de oorlog getekende generatie zonder hoop, geloof en idealen. De hoofdpersonen bedriegen elkaar, zijn wanhopig en hebben geen grenzen in hun seksuele omgang. Bovendien liet Hermans in het boek zien dat het Nederlands verzet tegen de Duitsers niet altijd even heldhaftig was. De personages in de wereld van Hermans proberen greep te krijgen op de wereld, maar dat is altijd tevergeefs. Uiteindelijk zijn ze gedesillusioneerd, ontgoocheld. Hermans noemt zichzelf ook ‘misantroop’ (iemand die mensen haat) en hij komt ook in interviews erg cynisch over. Hermans stond wel bekend als de meest gevreesde schrijver van Nederland, als de kwelgeest van de literatuur. -

Rory's List (In Alphabetical Order)

Rory's List (in alphabetical order) 1984 by George Orwell The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll (TBR) The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon An American Tragedy by Theodore Dreiser Angela's Ashes by Frank McCourt Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank Archidamian War by Donald Kagan The Art of Fiction by Henry James The Art of War by Sun Tzu As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner Atonement by Ian McEwan Autobiography of a Face by Lucy Grealy The Awakening by Kate Chopin Babe by Dick King-Smith Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women by Susan Faludi Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress by Dai Sijie Bel Canto by Ann Patchett The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath (TBR) Beloved by Toni Morrison Beowulf: A New Verse Translation by Seamus Heaney The Bhagava Gita The Bielski Brothers: The True Story of Three Men Who Defied the Nazis, Built a Village in the Forest, and Saved 1,200 Jews by Peter Duffy Bitch in Praise of Difficult Women by Elizabeth Wurtzel A Bolt from the Blue and Other Essays by Mary McCarthy Brave New World by Aldous Huxley Brick Lane by Monica Ali Bridgadoon by Alan Jay Lerner Candide by Voltaire The Canterbury Tales by Chaucer Carrie by Stephen King Catch-22 by Joseph Heller The Catcher in the Rye by J. D. Salinger Charlotte's Web by E. B. White The Children's Hour by Lillian Hellman Christine by Stephen King A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess The Code of the Woosters by P.G. -

181284Pub.Pdf

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/181284 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-09-29 and may be subject to change. Review Edwin Praat, Verrek, het is geen kunstenaar. Gerard Reve en het schrijverschap (Amsterdam: AUP, 2014) Sander Bax, De Mulisch Mythe. Harry Mulisch: schrijver, intellectueel, icoon (Amsterdam: Meulenhoff, 2015) Daan Rutten, De ernst van het spel. Willem Frederik Hermans en de ethiek van de persoonlijke mythologie (Hilversum: Verloren, 2016) Roel Smeets, Radboud University Nijmegen Every national literary field has its darlings and this is true for Dutch literature as well. After the Second World War, an obsession emerged with three writers that have been referred to as the ‘Great Three’: Harry Mulisch (1927-2010), Gerard Reve (1923-2006) and Willem Frederik Hermans (1921-1995). For decades, Simon Vestdijk (1898-1971) was considered to be the nestor of Dutch literature, yet with his death emerged the need for new grand names.1 Mulisch, Reve and Hermans were coined as the Great Three in the 1970s, and their reputation has been reiterated time and again and consolidated by critics as well as in literary histories and schoolbooks. A widespread attention for these three post-World War II writers was set, both in- and outside the walls of academia, and the recent publication of three major studies attest to the continued interest for their work. Sander Bax’s De Mulisch Mythe. -

The Aggressive Logic of Singularity: Willem Frederik Hermans1 Frans Ruiter, University of Utrecht, and Wilbert Smulders, University of Utrecht

The Aggressive Logic of Singularity: Willem Frederik Hermans1 Frans Ruiter, University of Utrecht, and Wilbert Smulders, University of Utrecht Abstract: Willem Frederik Hermans is considered to be one of the major Dutch authors of the twentieth century. In his novels ideals of every kind are unmasked, and his Weltanschauung leaves little room for pursuing a ‘good life’. Nevertheless, there seems to be one option left to him, namely literature. In his poetic essays he explains that literature has nothing to do with escapism, but offers a vital way of facing the bleak facts of life. Literary critics and scholars have commented extensively on his poetic ideas, but have never truly addressed the riddle Hermans’ œuvre confronts us with: what might be the value of writing in a world without values? In this article we will focus on this paradoxical problem, which could perhaps be characterized as one of ‘aesthetics of nihilism’. We argue that Hermans’ so-called autonomous and a-political literary position can certainly be interpreted as a form of commitment that goes far beyond literature. We will first give an overview of Hermans’ work. Subsequently we will reflect on the social and cultural status of literary autonomy. Our main aim is to analyze a critical text by Hermans which seems clear at first sight but actually is rather enigmatic: the compact, well- known essay Antipathieke romanpersonages (‘Unsympathetic Fictional Characters’).2 Keywords: Literary Autonomy, Alterity, Willem Frederik Hermans Singularity: to Spring a Leak in the Fullness… In his autobiographical story Het grote medelijden (The Great Compassion) Hermans’ alter ego Richard Simmilion says about the people who surround him, i.e.