This Historic Space Northeast of National Statuary Hall Once Served

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2/1/75 - Mardi Gras Ball” of the Betty Ford White House Papers, 1973-1977 at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 2, folder “2/1/75 - Mardi Gras Ball” of the Betty Ford White House Papers, 1973-1977 at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Betty Ford donated to the United States of America her copyrights in all of her unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. A MARDI GRAS HISTORY Back in the early 1930's, United States Senator Joseph KING'S CAKE Eugene Ransdell invited a few fellow Louisianians to his Washington home for a get together. Out of this meeting grew 2 pounds cake flour 6 or roore eggs the Louisiana State Society and, in turn, the first Mardi Gras l cup sugar 1/4 cup warm mi lk Ball. The king of the first ball was the Honorable F. Edward 1/2 oz. yeast l/2oz. salt Hebert. The late Hale Boggs was king of the second ball . l pound butter Candies to decorate The Washington Mardi Gras Ball, of course, has its origins in the Nardi Gras celebration in New Orleans, which in turn dates Put I 1/2 pounds flour in mixing bowl. -

Cenotaphs Would Suggest a Friendship, Clay Begich 11 9 O’Neill Historic Congressional Cemetery and Calhoun Disliked Each Other in Life

with Henry Clay and Daniel Webster he set the terms of every important debate of the day. Calhoun was acknowledged by his contemporaries as a legitimate successor to George Washington, John Adams or Thomas Jefferson, but never gained the Revised 06.05.2020 presidency. R60/S146 Clinton 2 3 Tracy 13. HENRY CLAY (1777–1852) 1 Latrobe 4 Blount Known as the “Great Compromiser” for his ability to bring Thornton 5 others to agreement, he was the founder and leader of the Whig 6 Anderson Party and a leading advocate of programs for modernizing the economy, especially tariffs to protect industry, and a national 7 Lent bank; and internal improvements to promote canals, ports and railroads. As a war hawk in Congress demanding the War of Butler 14 ESTABLISHED 1807 1812, Clay made an immediate impact in his first congressional term, including becoming Speaker of the House. Although the 10 Boggs Association for the Preservation of closeness of their cenotaphs would suggest a friendship, Clay Begich 11 9 O’Neill Historic Congressional Cemetery and Calhoun disliked each other in life. Clay 12 Brademas 8 R60/S149 Calhoun 13 14. ANDREW PICKENS BUTLER (1796–1857) Walking Tour As the nation drifted toward war between the states, tensions CENOTAPHS rose even in the staid Senate Chamber of the U.S. Congress. When Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts disparaged Senator Andrew Butler of South Carolina (who was not istory comes to life in Congressional present) during a floor speech, Representative Preston Brooks Cemetery. The creak and clang of the of South Carolina, Butler’s cousin, took umbrage and returned wrought iron gate signals your arrival into to the Senate two days later and beat Sumner severely with a the early decades of our national heritage. -

House of Representatives June 5, 1962, at 12 O'clock Meridian

1962 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-· HOUSE 9601 Mr. Lincoln's word. is good enough for me .. COMMITTEE ON INTERSTATE AND The SPEAKER. Is there objection to The tyrant will not come to America from FOREIGN COMMERCE the request of the gentleman from across the seas. If he comes he will ride Michigan? down Pennsylvania A.venue from his inaugu Mr. CELI.ER. Mr. Speaker, I ask There was no objection ration and take his residence in the White unanimous consent that H.R. 10038, to House. We have, in the last 15 months in provide civil remedies to persons. dam the Congress, inadvertently and carelessly aged by unfair commercial activities in STATUTORY AWARD FOR APHONIA we must assume, moved at- a hellish rate to or affecting commerce, and H.R. 10124, establish preconditions of dictatorship. The Clerk called the bill (H.R. 10066) There will be no coup d' etat. Rather, at the be referred to the Committee on Inter to amend title 38 of the United States worst, there will be an extension and vigorous state and Foreign Commerce. They Code to provide additional compensa exercise of the powers we have granted. were improperly referred to the Commit tion for veterans suffering the loss or Is the matter beyond control? I do not tee on the Judiciary. The subject mat loss of use of both vocal chords, with know and you're not sure. In all sadness ter of these bills should be properly be resulting complete aphonia. I say I do not know. The ancients tell us fore the Committee on Interstate and that democracy degenerates into tyranny. -

Marie Corinne Claiborne “Lindy” Boggs by Abbey Herbert

Marie Corinne Claiborne “Lindy” Boggs By Abbey Herbert Presented by: Women’s Resource Center & NOLA4Women Designed by: the Donnelley Center Marie Corrine Claiborne Born in Louisiana on March 13, 1916, Marie Corinne Democratic National Convention where delegates Claiborne “Lindy” Boggs became one of the most chose Jimmy Carter as the presidential nominee. influential political leaders in Louisiana and the Throughout her career, Boggs fought tirelessly United States. She managed political campaigns for for gender and racial equality. Boggs fought for her husband, Hale Boggs, mothered three children the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and who all grew up to lead important lives, and became later The Equal Credit Opportunity Act of 1974, the first woman in Louisiana to be elected to the Head Start as well as many other programs to United States Congress. In her later career, she empower and uplift women, people of color, and the served as ambassador to the Holy See. Throughout her impoverished. The Equal Credit Opportunity Act eventful and unorthodox life, Boggs vehemently advocated originally prevented creditors from discriminating for women’s rights and minority rights during the backlash against applicants based on race, color, religion, against the Civil Rights Movement and the second wave or national origin. Boggs demonstrated her zeal to of feminism. protect women’s rights by demanding that “sex or On January 3, 1973, Hale Bogg’s seat in Congress as marital status” be incorporated into this law. She House Majority Leader was declared empty after his plane succeeded. Boggs dedicated herself to including women disappeared on a trip to Alaska. -

Cokie Roberts Oral History Interview Final Edited Transcript

Cokie Roberts Congressional Correspondent and Daughter of Representatives Hale and Lindy Boggs of Louisiana Oral History Interview Final Edited Transcript May 25, 2017 Office of the Historian U.S. House of Representatives Washington, D.C. “And so she [Lindy Boggs] was on the Banking Committee. They were marking up or writing a piece of legislation to end discrimination in lending. And the language said, ‘on the basis of race, national origin, or creed’—something like that. And as she told the story, she went into the back room and wrote in, in longhand, ‘or sex or marital status,’ and Xeroxed it, and brought it back into the committee, and said, ‘I’m sure this was just an omission on the part of my colleagues who are so distinguished.’ That’s how we got equal credit, ladies.” Cokie Roberts May 25, 2017 Table of Contents Interview Abstract i Interviewee Biography i Editing Practices ii Citation Information iii Interviewer Biographies iii Interview 1 Notes 29 Abstract On May 25, 2017, the Office of the House Historian participated in a live oral history event, “An Afternoon with Cokie Roberts,” hosted by the Capitol Visitor Center. Much of the interview focused on Cokie Roberts’ reflections of her mother Lindy Boggs whose half-century association with the House spanned her time as the spouse of Representative Hale Boggs and later as a Member of Congress for 18 years. Roberts discusses the successful partnership of her parents during Hale Boggs’ 14 terms in the House. She describes the significant role Lindy Boggs played in the daily operation of her husband’s congressional office as a political confidante and expert campaigner—a function that continued to grow and led to her overseeing much of the Louisiana district work when Hale Boggs won a spot in the Democratic House Leadership. -

![Presidential Files; Folder: 7/28/77 [2]; Container 34](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1583/presidential-files-folder-7-28-77-2-container-34-341583.webp)

Presidential Files; Folder: 7/28/77 [2]; Container 34

7/28/77 [2] Folder Citation: Collection: Office of Staff Secretary; Series: Presidential Files; Folder: 7/28/77 [2]; Container 34 To See Complete Finding Aid: http://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/library/findingaids/Staff_Secretary.pdf WITHDRAWAL SHEET (PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARIES) FORM OF CORRESPONDENTS OR TITLE DATE RESTRICTION DOCUMENT letter From President Carter to Sen. Inouye (5 pp.) 7/27/77 A w/att. Intelligence Oversight Board/ enclosed in Hutcheson to Frank Moore 7/28~~? r.l I I {)~ L 7 93 FILE LOCATION Carter Presidential Papers- Staff Of fcies, Off~£e of the Staff Sec.- Pres. Handwriting File 7/28777 [2] Box 41' RESTRICTION CODES (A) Closed by Executive Order 12356'governing access to national security information. B) Closed by statute or by the agency which originated the document. C) Closed in accordance with restrictions contained in the donor's deed of gift. t-· 1\TIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION. NA FORM 1429 (6-85) t ~ l-~~- ------------------------------~I . ( ~, 1. • I ' \ \ . • THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON July 28, 1977 ·I ! Frank Moore ( . I The attached was returned in the President's outbox. I . It is forwarded to you for appropriate handling. Rick Hutcheson cc: The Vice President Hamilton Jordan Bob Lipshutz Zbig Brzezinski • I Joe Dennin ! RE: LETTER TO SENATOR INOUYE ON INTELLIGENCE OVERSIGHT \ BOARD t ' . ·\ •I ' 1 THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON FOR STAFFING FOR INFORMATION FROH PRESIDENT'S OUTBOX LOG IN TO PRESIDENT TODAY z IMMEDIATE TURNAROUND 0 I H ~ ~·'-'\ 8 H c.... C. (Ji u >t ,::X: ~ / MONDALE ENROLLED BILL COSTANZA AGENCY REPORT EIZENSTAT CAB DECISION I JORDAN EXECUTIVE ORDER I LIPSHUTZ Comments due to / MOORE of'"• ~ ,_. -

TUESDAY, M Y 1, 1962 the President Met with the Following of The

TUESDAY, MAYMYI,1, 1962 9:459:45 -- 9:50 am The PrePresidentsident met with the following of the Worcester Junior Chamber of CommeCommerce,rce, MasMassachusettssachusetts in the Rose Garden: Don Cookson JJamesarne s Oulighan Larry Samberg JeffreyJeffrey Richard JohnJohn Klunk KennethKenneth ScScottott GeorgeGeorge Donatello EdwardEdward JaffeJaffe RichardRichard MulhernMulhern DanielDaniel MiduszenskiMiduszenski StazrosStazros GaniaGaniass LouiLouiss EdmondEdmond TheyThey werewere accorrpaccompaniedanied by CongresCongressmansman HaroldHarold D.D. DonohueDonohue - TUESDAY,TUESbAY J MAY 1, 1962 8:45 atn LEGISLATIVELEGI~LATIVE LEADERS BREAKFAST The{['he Vice President Speaker John W. McCormackMcCortnack Senator Mike Mansfield SenatorSenato r HubertHube rt HumphreyHUInphrey Senator George SmatherStnathers s CongressmanCongresstnan Carl Albert CongressmanCongresstnan Hale BoggBoggs s Hon. Lawrence O'Brien Hon. Kenneth O'Donnell0 'Donnell Hon. Pierre Salinger Hon. Theodore Sorensen 9:35 amatn The President arrived in the office. (See insert opposite page) 10:32 - 10:55 amatn The President mettnet with a delegation fromfrotn tktre Friends'Friends I "Witness for World Order": Henry J. Cadbury, Haverford, Pa. Founder of the AmericanAtnerican Friends Service CommitteeCOtntnittee ( David Hartsough, Glen Mills, Pennsylvania Senior at Howard University Mrs. Dorothy Hutchinson, Jenkintown, Pa. Opening speaker, the Friends WitnessWitnes~ for World Order Mr. Samuel Levering, Arararat, Virginia Chairman of the Board on Peace and.and .... Social Concerns Edward F. Snyder, College Park, Md. Executive Secretary of the Friends Committe on National Legislation George Willoughby, Blackwood Terrace, N. J. Member of the crew of the Golden Rule (ship) and the San Francisco to Moscow Peace Walk (Hon. McGeorgeMkGeorge Bundy) (General Chester V. Clifton 10:57 - 11:02 am (Congre(Congresswomansswoman Edith Green, Oregon) OFF TRECO 11:15 - 11:58 am H. -

Ronald Reagan, Louisiana, and the 1980 Presidential Election Matthew Ad Vid Caillet Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2011 "Are you better off "; Ronald Reagan, Louisiana, and the 1980 Presidential election Matthew aD vid Caillet Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Caillet, Matthew David, ""Are you better off"; Ronald Reagan, Louisiana, and the 1980 Presidential election" (2011). LSU Master's Theses. 2956. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2956 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ―ARE YOU BETTER OFF‖; RONALD REAGAN, LOUISIANA, AND THE 1980 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History By Matthew David Caillet B.A. and B.S., Louisiana State University, 2009 May 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to many people for the completion of this thesis. Particularly, I cannot express how thankful I am for the guidance and assistance I received from my major professor, Dr. David Culbert, in researching, drafting, and editing my thesis. I would also like to thank Dr. Wayne Parent and Dr. Alecia Long for having agreed to serve on my thesis committee and for their suggestions and input, as well. -

5/14/80; Container 162 to Se

5/14/80 Folder Citation: Collection: Office of Staff Secretary; Series: Presidential Files; Folder: 5/14/80; Container 162 To See Complete Finding Aid: http://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/library/findingaids/Staff_Secretary.pdf t. THIRD REVISION 5/14/80 11:00 a.m. THE PRESIDENT'S SCHEDULE NOT ISSUED Wednesday - May 14, 1980 7:30 Dr. Zbigniew Brzezinski - �he Oval Office. ) 8:00 Breakfast to discuss Cuban Refugee Situation. ( 60 mins.) (Mr. Jack Watson) - The Cabinet Room. # 9:4 5 Meeting with Mr. Gamal a1 Sadat and -!-irs. (5 mins.) Dina al Sadat. (Mrs. Rosalynn Carter) The Oval Office 10:00 Mr. Hamilton Jordan and Mr. Frank Moore. The Oval Office. 11:10 Depart South Grounds via Motorcade en route . , HHH Building . 11:15 Launching Ceremony for New Department of HHS. (25 mins.) 11:45 Arrive South Lawn from HHH Building. / 11:55 Meeting with Prime Minister (John) David ( 5 mins.) Gibbons of Bermuda. (Hr. Frank Moore) The Oval Office / 1:00 Meeting with Auto Industry Executives and ( 4 5 mins.) Doug Fraser. (Mr. Stuart Eizenstat) -- The Cabinet Room. 2:30 Mr. Hedley Donovan - The Oval Office. :jl: 4:00 Meeting with Congressional Leadership on (10 mins.) Refugee Policy - The Cabinet Room (Frank Moore) �� 4:30 Announcement of Refuaee Policv - The Press Lobby (5 r:'.ins.) '(Stu E izenstat) - - - -·-·-··/�-�-�-�---·---- ·-·--·-·---- - --� Meeting with United States Delegation to the (10 mins.) International Labor Conference. (Mr. Landon Butler) - The Cabinet Room. "Thank You" Reception for Supporters. (The State Dining Room) SECOND REVISION 5/13/80 6:40 p.m. THE PRESIDENT'S SCHEDULE NOT ISSUED Wednesday - May 14, 1980 7:30 Dr. -

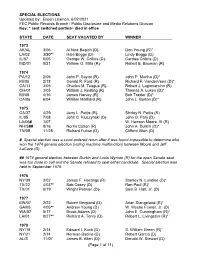

Special Election Dates

SPECIAL ELECTIONS Updated by: Eileen Leamon, 6/02/2021 FEC Public Records Branch / Public Disclosure and Media Relations Division Key: * seat switched parties/- died in office STATE DATE SEAT VACATED BY WINNER 1973 AK/AL 3/06 Al Nick Begich (D)- Don Young (R)* LA/02 3/20** Hale Boggs (D)- Lindy Boggs (D) IL/07 6/05 George W. Collins (D)- Cardiss Collins (D) MD/01 8/21 William O. Mills (R)- Robert E. Bauman (R) 1974 PA/12 2/05 John P. Saylor (R)- John P. Murtha (D)* MI/05 2/18 Gerald R. Ford (R) Richard F. VanderVeen (D)* CA/13 3/05 Charles M. Teague (R)- Robert J. Lagomarsino (R) OH/01 3/05 William J. Keating (R) Thomas A. Luken (D)* MI/08 4/16 James Harvey (R) Bob Traxler (D)* CA/06 6/04 William Mailliard (R) John L. Burton (D)* 1975 CA/37 4/29 Jerry L. Pettis (R)- Shirley N. Pettis (R) IL/05 7/08 John C. Kluczynski (D)- John G. Fary (D) LA/06# 1/07 W. Henson Moore, III (R) NH/S## 9/16 Norris Cotton (R) John A. Durkin (D)* TN/05 11/25 Richard Fulton (D) Clifford Allen (D) # Special election was a court-ordered rerun after it was found impossible to determine who won the 1974 general election (voting machine malfunction) between Moore and Jeff LaCaze (D). ## 1974 general election between Durkin and Louis Wyman (R) for the open Senate seat was too close to call and the Senate refused to seat either candidate. Special election was held in September 1975. -

H. Doc. 108-222

SEVENTY-SEVENTH CONGRESS JANUARY 3, 1941, TO JANUARY 3, 1943 FIRST SESSION—January 3, 1941, to January 2, 1942 SECOND SESSION—January 5, 1942, 1 to December 16, 1942 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES 2—JOHN N. GARNER, 3 of Texas; HENRY A. WALLACE, 4 of Iowa PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—PAT HARRISON, 5 of Mississippi; CARTER GLASS, 6 of Virginia SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—EDWIN A. HALSEY, of Virginia SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—CHESLEY W. JURNEY, of Texas SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—SAM RAYBURN, 7 of Texas CLERK OF THE HOUSE—SOUTH TRIMBLE, 8 of Kentucky SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—KENNETH ROMNEY, of Montana DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—JOSEPH J. SINNOTT, of Virginia POSTMASTER OF THE HOUSE—FINIS E. SCOTT ALABAMA ARKANSAS Albert E. Carter, Oakland SENATORS John H. Tolan, Oakland SENATORS John Z. Anderson, San Juan Bautista Hattie W. Caraway, Jonesboro John H. Bankhead II, Jasper Bertrand W. Gearhart, Fresno John E. Miller, 11 Searcy Lister Hill, Montgomery Alfred J. Elliott, Tulare George Lloyd Spencer, 12 Hope Carl Hinshaw, Pasadena REPRESENTATIVES REPRESENTATIVES Jerry Voorhis, San Dimas Frank W. Boykin, Mobile E. C. Gathings, West Memphis Charles Kramer, Los Angeles George M. Grant, Troy Wilbur D. Mills, Kensett Thomas F. Ford, Los Angeles Henry B. Steagall, Ozark Clyde T. Ellis, Bentonville John M. Costello, Hollywood Sam Hobbs, Selma Fadjo Cravens, Fort Smith Leland M. Ford, Santa Monica Joe Starnes, Guntersville David D. Terry, Little Rock Lee E. Geyer, 14 Gardena Pete Jarman, Livingston W. F. Norrell, Monticello Cecil R. King, 15 Los Angeles Walter W. -

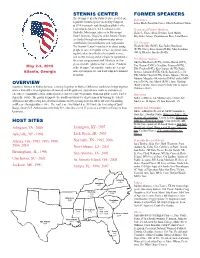

Fact Sheet 10.Indd

STENNIS CENTER FORMER SPEAKERS The Stennis Center for Public Service is a federal, First Ladies legislative branch agency created by Congress Laura Bush, Rosalynn Carter, Hillary Rodham Clinton in 1988 to promote and strengthen public service leadership in America. It is headquartered in Presidential Cabinet Members Starkville, Mississippi, adjacent to Mississippi Elaine L. Chao, Alexis Herman, Lynn Martin, State University. Programs of the Stennis Center Kay Coles James, Condoleezza Rice, Janet Reno are funded through an endowment plus private contributions from foundations and corporations. U.S. Senators The Stennis Center’s mandate is to attract young Elizabeth Dole (R-NC), Kay Bailey Hutchison people to careers in public service, to provide train- (R-TX), Nancy Kassebaum (R-KS), Mary Landrieu ing for leaders in or likely to be in public service, (D-LA), Blanche Lincoln (D-AR) and to offer training and development opportunities U.S. Representatives for senior congressional staff, Members of Con- Marsha Blackburn (R-TN), Corrine Brown (D-FL), gress, and other public service leaders. Products May 2-3, 2010 Eva Clayton (D-NC), Geraldine Ferraro (D-NY), of the Stennis Center include conferences, semi- Tillie Fowler (R-FL), Kay Granger (R-TX), Eddie Atlanta, Georgia nars, special projects, and leadership development Bernice Johnson (D-TX), Sheila Jackson Lee (D- programs. TX), Marilyn Lloyd (D-TN), Denise Majette ( D-GA), Marjorie Margolies-Mezvinsky (D-PA) Cynthia McK- inney (D-GA), Sue Myrick (R-NC), Anne Northup OVERVIEW (R-KY), Debbie Wasserman Schultz (D-FL), Karen Southern Women in Public Service: Coming Together to Make a Difference conference brings together Thurman (D-FL) women from different backgrounds—Democrats and Republicans, stay-at-home mothers and business executives, community leaders, political novices and veterans—to promote women in public service leader- Governors ship in the South.