Cokie Roberts Oral History Interview Final Edited Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

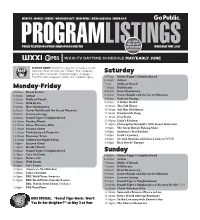

WXXI Program Guide | May 2021

WXXI-TV | WORLD | CREATE | WXXI KIDS 24/7 | WXXI NEWS | WXXI CLASSICAL | WRUR 88.5 SEE CENTER PAGES OF CITY PROGRAMPUBLIC TELEVISION & PUBLIC RADIO FOR ROCHESTER LISTINGSFOR WXXI SHOW MAY/EARLY JUNE 2021 HIGHLIGHTS! WXXI-TV DAYTIME SCHEDULE MAY/EARLY JUNE PLEASE NOTE: WXXI-TV’s daytime schedule listed here runs from 6:00am to 7:00pm. The complete prime time television schedule begins on page 2. Saturday The PBS Kids programs below are shaded in gray. 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 6:30am Arthur 7vam Molly of Denali Monday-Friday 7:30am Wild Kratts 6:00am Ready Jet Go! 8:00am Hero Elementary 6:30am Arthur 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 7:00am Molly of Denali 9:00am Curious George 7:30am Wild Kratts 9:30am A Wider World 8:00am Hero Elementary 10:00am This Old House 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 10:30am Ask This Old House 9:00am Curious George 11:00am Woodsmith Shop 9:30am Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood 11:30am Ciao Italia 10:00am Donkey Hodie 12:00pm Lidia’s Kitchen 10:30am Elinor Wonders Why 12:30pm Christopher Kimball’s Milk Street Television 11:00am Sesame Street 1:00pm The Great British Baking Show 11:30am Pinkalicious & Peterrific 2:00pm America’s Test Kitchen 12:00pm Dinosaur Train 2:30pm Cook’s Country 12:30pm Clifford the Big Red Dog 3:00pm Second Opinion with Joan Lunden (WXXI) 1:00pm Sesame Street 3:30pm Rick Steves’ Europe 1:30pm Donkey Hodie 2:00pm Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood Sunday 2:30pm Let’s Go Luna! 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 3:00pm Nature Cat 6:30am Arthur 3:30pm Wild Kratts 7:00am Molly -

2/1/75 - Mardi Gras Ball” of the Betty Ford White House Papers, 1973-1977 at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 2, folder “2/1/75 - Mardi Gras Ball” of the Betty Ford White House Papers, 1973-1977 at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Betty Ford donated to the United States of America her copyrights in all of her unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. A MARDI GRAS HISTORY Back in the early 1930's, United States Senator Joseph KING'S CAKE Eugene Ransdell invited a few fellow Louisianians to his Washington home for a get together. Out of this meeting grew 2 pounds cake flour 6 or roore eggs the Louisiana State Society and, in turn, the first Mardi Gras l cup sugar 1/4 cup warm mi lk Ball. The king of the first ball was the Honorable F. Edward 1/2 oz. yeast l/2oz. salt Hebert. The late Hale Boggs was king of the second ball . l pound butter Candies to decorate The Washington Mardi Gras Ball, of course, has its origins in the Nardi Gras celebration in New Orleans, which in turn dates Put I 1/2 pounds flour in mixing bowl. -

Cenotaphs Would Suggest a Friendship, Clay Begich 11 9 O’Neill Historic Congressional Cemetery and Calhoun Disliked Each Other in Life

with Henry Clay and Daniel Webster he set the terms of every important debate of the day. Calhoun was acknowledged by his contemporaries as a legitimate successor to George Washington, John Adams or Thomas Jefferson, but never gained the Revised 06.05.2020 presidency. R60/S146 Clinton 2 3 Tracy 13. HENRY CLAY (1777–1852) 1 Latrobe 4 Blount Known as the “Great Compromiser” for his ability to bring Thornton 5 others to agreement, he was the founder and leader of the Whig 6 Anderson Party and a leading advocate of programs for modernizing the economy, especially tariffs to protect industry, and a national 7 Lent bank; and internal improvements to promote canals, ports and railroads. As a war hawk in Congress demanding the War of Butler 14 ESTABLISHED 1807 1812, Clay made an immediate impact in his first congressional term, including becoming Speaker of the House. Although the 10 Boggs Association for the Preservation of closeness of their cenotaphs would suggest a friendship, Clay Begich 11 9 O’Neill Historic Congressional Cemetery and Calhoun disliked each other in life. Clay 12 Brademas 8 R60/S149 Calhoun 13 14. ANDREW PICKENS BUTLER (1796–1857) Walking Tour As the nation drifted toward war between the states, tensions CENOTAPHS rose even in the staid Senate Chamber of the U.S. Congress. When Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts disparaged Senator Andrew Butler of South Carolina (who was not istory comes to life in Congressional present) during a floor speech, Representative Preston Brooks Cemetery. The creak and clang of the of South Carolina, Butler’s cousin, took umbrage and returned wrought iron gate signals your arrival into to the Senate two days later and beat Sumner severely with a the early decades of our national heritage. -

PARTNERS in Hope and Discovery Where the Power of Childhood Meets the Power of Research

PARTNERS in Hope and Discovery Where the power of childhood meets the power of research 2016 ANNUAL REPORT WHERE BREAKTHROUGHS HAPPEN The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is the world’s premier biomedical research institution—and the breakthroughs that happen here are the first steps toward eradicating diseases, easing pain, and making better lives possible. None Inn residents of these medical advances would be participated possible without the people who drive them: children, families and caregivers, in 283 clinicians and staff—the community The CLINICAL Children’s Inn brings together. The Inn TRIALS provides relief, support, and strength to at the NIH these pioneers whose participation in in FY16 medical trials at the NIH can change the story for children around the world. Inn residents are a part of pediatric protocols in 15 of the 27 INSTITUTES and CENTERS at the NIH On the cover: Inn resident Reem, age 7 from Egypt, with her NIH physician, Dr. Neal Young. She is being treated for aplastic anemia at the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. As partners in discovery and care, OUR VISION we strive for the day when no family endures the heartbreak of a seriously ill child. Letter from the Chair of the Board and Chief Executive Officer The Inn’s Board of Directors had an eventful We are so grateful to you: our donors, volunteers, year. We have worked diligently to restructure and friends, who help The Children’s Inn make a and prepare The Inn for the future, and recently profound impact on the lives of the NIH’s young- welcomed some talented new members to our est patients. -

House of Representatives June 5, 1962, at 12 O'clock Meridian

1962 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-· HOUSE 9601 Mr. Lincoln's word. is good enough for me .. COMMITTEE ON INTERSTATE AND The SPEAKER. Is there objection to The tyrant will not come to America from FOREIGN COMMERCE the request of the gentleman from across the seas. If he comes he will ride Michigan? down Pennsylvania A.venue from his inaugu Mr. CELI.ER. Mr. Speaker, I ask There was no objection ration and take his residence in the White unanimous consent that H.R. 10038, to House. We have, in the last 15 months in provide civil remedies to persons. dam the Congress, inadvertently and carelessly aged by unfair commercial activities in STATUTORY AWARD FOR APHONIA we must assume, moved at- a hellish rate to or affecting commerce, and H.R. 10124, establish preconditions of dictatorship. The Clerk called the bill (H.R. 10066) There will be no coup d' etat. Rather, at the be referred to the Committee on Inter to amend title 38 of the United States worst, there will be an extension and vigorous state and Foreign Commerce. They Code to provide additional compensa exercise of the powers we have granted. were improperly referred to the Commit tion for veterans suffering the loss or Is the matter beyond control? I do not tee on the Judiciary. The subject mat loss of use of both vocal chords, with know and you're not sure. In all sadness ter of these bills should be properly be resulting complete aphonia. I say I do not know. The ancients tell us fore the Committee on Interstate and that democracy degenerates into tyranny. -

Marie Corinne Claiborne “Lindy” Boggs by Abbey Herbert

Marie Corinne Claiborne “Lindy” Boggs By Abbey Herbert Presented by: Women’s Resource Center & NOLA4Women Designed by: the Donnelley Center Marie Corrine Claiborne Born in Louisiana on March 13, 1916, Marie Corinne Democratic National Convention where delegates Claiborne “Lindy” Boggs became one of the most chose Jimmy Carter as the presidential nominee. influential political leaders in Louisiana and the Throughout her career, Boggs fought tirelessly United States. She managed political campaigns for for gender and racial equality. Boggs fought for her husband, Hale Boggs, mothered three children the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and who all grew up to lead important lives, and became later The Equal Credit Opportunity Act of 1974, the first woman in Louisiana to be elected to the Head Start as well as many other programs to United States Congress. In her later career, she empower and uplift women, people of color, and the served as ambassador to the Holy See. Throughout her impoverished. The Equal Credit Opportunity Act eventful and unorthodox life, Boggs vehemently advocated originally prevented creditors from discriminating for women’s rights and minority rights during the backlash against applicants based on race, color, religion, against the Civil Rights Movement and the second wave or national origin. Boggs demonstrated her zeal to of feminism. protect women’s rights by demanding that “sex or On January 3, 1973, Hale Bogg’s seat in Congress as marital status” be incorporated into this law. She House Majority Leader was declared empty after his plane succeeded. Boggs dedicated herself to including women disappeared on a trip to Alaska. -

Robert W. Edgar, General Secretary, National Council of Churches MR

Robert W. Edgar, General Secretary, National Council of Churches MR. EDGAR: I'm pleased to be here, not only to say a word of focus and commitment to the legacy of Geno, but sitting side-by-9side with all of these colleagues, and especially Stu Eizenstat. Stu was the domestic policy adviser to President Carter, and I was a young congressperson elected by accident in the Watergate years, and had the chance and the opportunity for the four years of the Carter administration -- although I served for six terms -- to work with Stu on many domestic issues, especially water policy that became so controversial in those years. So it's great to reconnect with him, and it's great to be here with you. As the senator indicated, Rosa Parks died yesterday. I mark my entry into political life and the bridge between my faith life as a pastor in Philadelphia, an urban pastor, who founded the first shelter for homeless women in the city of Philadelphia, I mark my bridge from my faith tradition to politics, based on the life and work of Dr. Martin Luther King. And the civil rights movement had an impact, not just on the black community but on the white community, as well. I grew up in a white suburb of Philadelphia. I grew up in a blue-collar working-class family. But I 20didn't really see poverty until I was about a senior in high school. And the United Methodist Church had what they called "come see" tours, where they literally put young people on buses and took them into the city of Philadelphia, and into the city of Chester, to see with their own eyes the impact of policies on the poor. -

How First-Term Members Enter the House Burdett

Coming into the Country: How First-Term Members Enter the House Burdett Loomis University of Kansas and The Brookings Institution November 17, 2000 In mulling over how newly elected Members of Congress (henceforth MCs1) “enter” the U.S. House of Representatives, I have been drawn back to John McPhee’s classic book on Alaska, Coming into the Country. Without pushing the analogy too far, the Congress is a lot like Alaska, especially for a greenhorn. Congress is large, both in terms of numbers (435 members and 8000 or so staffers) and geographic scope (from Seattle to Palm Beach, Manhattan to El Paso). Even Capitol Hill is difficult to navigate, as it requires a good bit of exploration to get the lay of the land. The congressional wilderness is real, whether in unexplored regions of the Rayburn Building sub-basements or the distant corridors of the fifth floor of the Cannon Office Building, where a sturdy band of first-term MCs must establish their Washington outposts. Although both the state of Alaska and the House of Representatives are governed by laws and rules, many tricks of survival are learned informally -- in a hurried conversation at a reception or at the House gym, in the wake of a pick-up basketball game. In the end, there’s no single understanding of Alaska – it’s too big, too complex. Nor is there any single way to grasp the House. It’s partisan, but sometimes resistant to partisanship. It’s welcoming and alienating. It’s about Capitol Hill, but also about 435 distinct constituencies. -

Fiscal 2019 Congressional Budget Justification

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS FISCAL 2019 BUDGET JUSTIFICATION SUBMITTED FOR USE OF THE COMMITTEES ON APPROPRIATIONS LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Provided by Brian Williams TABLE OF CONTENTS LIBRARY OF CONGRESS OVERVIEW FISCAL 2019 .................................................................................1 ORGANIZATION CHART ..................................................................................................................................7 SUMMARY TABLES ...........................................................................................................................................9 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, SALARIES AND EXPENSES 17 OFFICE OF THE LIBRARIAN .................................................................................................................................21 Fiscal 2019 Program Changes ..................................................................................................................24 Librarian’s Office ....................................................................................................................................... 29 Office of the Chief Financial Officer ..........................................................................................................39 Integrated Support Services .....................................................................................................................43 OFFICE OF THE CHIEF INFORMATION OFFICER ...............................................................................................47 Fiscal 2019 Program -

![Presidential Files; Folder: 7/28/77 [2]; Container 34](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1583/presidential-files-folder-7-28-77-2-container-34-341583.webp)

Presidential Files; Folder: 7/28/77 [2]; Container 34

7/28/77 [2] Folder Citation: Collection: Office of Staff Secretary; Series: Presidential Files; Folder: 7/28/77 [2]; Container 34 To See Complete Finding Aid: http://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/library/findingaids/Staff_Secretary.pdf WITHDRAWAL SHEET (PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARIES) FORM OF CORRESPONDENTS OR TITLE DATE RESTRICTION DOCUMENT letter From President Carter to Sen. Inouye (5 pp.) 7/27/77 A w/att. Intelligence Oversight Board/ enclosed in Hutcheson to Frank Moore 7/28~~? r.l I I {)~ L 7 93 FILE LOCATION Carter Presidential Papers- Staff Of fcies, Off~£e of the Staff Sec.- Pres. Handwriting File 7/28777 [2] Box 41' RESTRICTION CODES (A) Closed by Executive Order 12356'governing access to national security information. B) Closed by statute or by the agency which originated the document. C) Closed in accordance with restrictions contained in the donor's deed of gift. t-· 1\TIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION. NA FORM 1429 (6-85) t ~ l-~~- ------------------------------~I . ( ~, 1. • I ' \ \ . • THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON July 28, 1977 ·I ! Frank Moore ( . I The attached was returned in the President's outbox. I . It is forwarded to you for appropriate handling. Rick Hutcheson cc: The Vice President Hamilton Jordan Bob Lipshutz Zbig Brzezinski • I Joe Dennin ! RE: LETTER TO SENATOR INOUYE ON INTELLIGENCE OVERSIGHT \ BOARD t ' . ·\ •I ' 1 THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON FOR STAFFING FOR INFORMATION FROH PRESIDENT'S OUTBOX LOG IN TO PRESIDENT TODAY z IMMEDIATE TURNAROUND 0 I H ~ ~·'-'\ 8 H c.... C. (Ji u >t ,::X: ~ / MONDALE ENROLLED BILL COSTANZA AGENCY REPORT EIZENSTAT CAB DECISION I JORDAN EXECUTIVE ORDER I LIPSHUTZ Comments due to / MOORE of'"• ~ ,_. -

The Effects of Secret Voting Procedures on Political Behavior

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Voting Alone: The Effects of Secret Voting Procedures on Political Behavior A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science by Scott M. Guenther Committee in charge: Professor James Fowler, Chair Professor Samuel Kernell, Co-Chair Professor Julie Cullen Professor Seth Hill Professor Thad Kousser 2016 Copyright Scott M. Guenther, 2016 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Scott M. Guenther is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-Chair Chair University of California, San Diego 2016 iii DEDICATION To my parents. iv EPIGRAPH Three may keep a secret, if two of them are dead. { Benjamin Franklin v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page................................... iii Dedication...................................... iv Epigraph......................................v Table of Contents.................................. vi List of Figures................................... viii List of Tables.................................... ix Acknowledgements.................................x Vita......................................... xiv Abstract of the Dissertation............................ xv Chapter 1 Introduction: Secrecy and Voting.................1 1.1 History of Secret Voting...................2 1.2 Conceptual Issues.......................5 1.2.1 Internal Secrecy....................6 1.2.2 External Secrecy...................7 1.3 Electoral Regimes.......................8 -

Ronald Reagan, Louisiana, and the 1980 Presidential Election Matthew Ad Vid Caillet Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2011 "Are you better off "; Ronald Reagan, Louisiana, and the 1980 Presidential election Matthew aD vid Caillet Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Caillet, Matthew David, ""Are you better off"; Ronald Reagan, Louisiana, and the 1980 Presidential election" (2011). LSU Master's Theses. 2956. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2956 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ―ARE YOU BETTER OFF‖; RONALD REAGAN, LOUISIANA, AND THE 1980 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History By Matthew David Caillet B.A. and B.S., Louisiana State University, 2009 May 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to many people for the completion of this thesis. Particularly, I cannot express how thankful I am for the guidance and assistance I received from my major professor, Dr. David Culbert, in researching, drafting, and editing my thesis. I would also like to thank Dr. Wayne Parent and Dr. Alecia Long for having agreed to serve on my thesis committee and for their suggestions and input, as well.