Wildlife-Human Interactions in National Parks in Canada and the USA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Subject Index Directory of Newfoundland and Labrador

Subject Index Directory of Newfoundland and Labrador Magazines | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z A [top] 4-H clubs Communico Echo Actors CARNL knowledge Adult Education Adult craft education NLAAE Newsletter Soundbone Advertising Ad libs Bargain Finder Aged 50 Plus 50+ Newsletter Cornucopia Encore magazine Newfoundland Alzheimer Association Newsletter Newfoundland and Labrador Recreation Advisory Council for Special Groups NLAA Newsletter R. T. A. Newsletter Senior Voice, The Senior Citizen, The Senior's Pride Seniors' News, The Signal, The Western Retired Teachers Newsletter Agriculture Decks awash Information for farmers Newfoundland Agricultural Society. Quarterly Journal of the Newfoundland Dept. of Mines and Resources Newsletter Newfoundland Farm Forum Sheep Producers Association of Newfoundland and Labrador Newsletter AIDS Reaching Out Alcoholic Beverages Beckett on Wine Roots Talk Winerack Alcoholism Alcoholism and Drug Addiction Foundation of Newfoundland and Labrador. Newsletter Banner of temperance Highlights Labrador Inuit Alcohol and Drug Abuse Program Alternate Alternate press Current Downtown Press Alumni Luminus OMA Bulletin Spencer Letter Alzheimer's disease Newfoundland Alzheimer Association Newsletter Anglican Church Angeles Avalon Battalion bugle Bishop's newsletter Diocesan magazine Newfoundland Churchman, The Parish Contact, The St. Thomas' Church Bulletin St. Martin's Bridge Trinity Curate West Coast Evangelist Animal Welfare Newfoundland Poney Care Inc. Newfoundland Pony Society Quarterly Newsletter SPCA Newspaws Aquaculture Aqua News Cod Farm News Newfoundland Aquaculture Association Archaeology Archaeology in Newfoundland & Labrador Avalon Chronicles From the Dig Marine Man Port au Choix National Historic Site Newsletter Rooms Update, The Architecture Goulds Historical Society. -

Publisher Index Directory of Newfoundland and Labrador Magazines

Publisher Index Directory of Newfoundland and Labrador Magazines | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z A Aardvark Communications Decks Awash Abitibi-Price Inc. Abitibi-Price Grand Falls News Abitibi-Price Stephenville News AdCom Publishing Ltd. This Week Advocate Pub. Co. Favourite, The Newfoundland Magazine and Commercial Advertiser Agnes Pratt Home Agnes Pratt newsletter Air Transport Command. North Atlantic Wing Harmoneer Alcoholism and Drug Dependency Commission of Newfoundland and Labrador Highlights Allied Nfld. Publications Newfoundland Profile Alternative Bookstore Co-operative Alternates Aluminum Company of Canada Newfluor News Amalgamated Senior Citizens Association of Newfoundland Ltd. Seniors' News, The Anglican Church of Canada. Diocese of Newfoundland Bishop's news-letter Diocesan magazine Newfoundland Churchman Anglo-Newfoundland Development Co. AND news Price News-Log Price facts and figures Argentia Base Ordnance Office Ordnance News Arnold's Cove Development Committee Cove, The Art Gallery of Newfoundland and Labrador Insight Arts and Culture Centre Showtime Association of Catholic Trade Unionists. St. John's Chapter. ACTU-ANA Association of Engineering Technicians and Technologists of Newfoundland AETTN Newsletter Association of Newfoundland and Labrador Archivists ANLA bulletin Association of Newfoundland Psychologists Newfoundland Psychologist Association of Newfoundland Surveyors Newfoundland Surveyor Association of Professional Engineers of Newfoundland Newfoundland and Labrador Engineer. Association of Registered Nurses of Newfoundland and Labrador ARNNL Access Association of Early Childhood Educators of Newfoundland and Labrador AECENL Quarterly Atkinson & Associates Ltd. Nickelodeon Atlantic Cool Climate Crop Research Centre Crops Communique Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency Newfoundland Interaction Atlantic Fisheries Development Program Project Summary Atlantic Focus Pub. -

Gros Morne National Park

DNA Barcode-based Assessment of Arthropod Diversity in Canada’s National Parks: Progress Report for Gros Morne National Park Report prepared by the Bio-Inventory and Collections Unit, Biodiversity Institute of Ontario, University of Guelph December 2014 1 The Biodiversity Institute of Ontario at the University of Guelph is an institute dedicated to the study of biodiversity at multiple levels of biological organization, with particular emphasis placed upon the study of biodiversity at the species level. Founded in 2007, BIO is the birthplace of the field of DNA barcoding, whereby short, standardized gene sequences are used to accelerate species discovery and identification. There are four units with complementary mandates that are housed within BIO and interact to further knowledge of biodiversity. www.biodiversity.uoguelph.ca Twitter handle @BIO_Outreach International Barcode of Life Project www.ibol.org Canadian Centre for DNA Barcoding www.ccdb.ca Barcode of Life Datasystems www.boldsystems.org BIObus www.biobus.ca Twitter handle @BIObus_Canada School Malaise Trap Program www.malaiseprogram.ca DNA Barcoding blog www.dna-barcoding.blogspot.ca International Barcode of Life Conference 2015 www.dnabarcodes2015.org 2 INTRODUCTION The Canadian National Parks (CNP) Malaise The CNP Malaise Program was initiated in 2012 Program, a collaboration between Parks Canada with the participation of 14 national parks in and the Biodiversity Institute of Ontario (BIO), Central and Western Canada. In 2013, an represents a first step toward the acquisition of additional 14 parks were involved, from Rouge detailed temporal and spatial information on National Urban Park to Terra Nova National terrestrial arthropod communities across Park (Figure 1). -

2022 Atlantic Canada Brochure! We Especially Appreciate Your Interest in Our Region Considering the Uncertainty As to When You Will Be Able to Visit Us

Showcasing ATLANTIC CANADA for over 50 YEARS s Cove ’ Peggy Scoria Nova Tourism Credit: 1-800-565-7173 | www.atlantictours.com LABRADOR 1 - 800 - 565 - 7173 |www.atlantictours.com 7173 Where to Find Us 22 Waddell Avenue, Suite 101 | Dartmouth, NS | B3B 1K3 www.atlantictours.com | [email protected] T. 902-423-7172 | TF. 1-800-565-7173 | F. 902-425-3596 2 Thank you for viewing our 2022 Atlantic Canada brochure! We especially appreciate your interest in our region considering the uncertainty as to when you will be able to visit us. When you can, we will welcome you with open arms and our renowned East Coast hospitality. We can’t wait to showcase Atlantic Canada, our home, to our friends all across the world again! Our signature tours of Atlantic Canada are typically guaranteed to travel; however, considering the pandemic, this might not be pos- sible in 2021. We will do our absolute best to provide as much notice as possible if it becomes necessary to cancel a departure, and if the pandemic affects your ability to travel, we will work with you to change your arrangements to an alternate date in the future. When looking at vacation options, please know that we are based in Atlantic Canada, and our Tour Director Team all live in Atlantic Canada. We live it, we love, and we know it! All Escorted tours include Transportation, Atlantic Canada Tour Director, Accommodations, Meals as Noted, and Fees for all Sightsee- ing Referenced. All Self-Drive Vacations include Accommodations, Meals as Noted, and Fees for all Sightseeing Referenced. -

Parks Canada Agency

Parks Canada Agency Application for Filming in Newfoundland East Field Unit Terra Nova National Park and Signal Hill, Cape Spear Lighthouse, Ryan Premises, Hawthorne Cottage, and Castle Hill National Historic Sites of Canada Thank you for your interest in filming in our national parks and national historic sites. To help expedite this process for you, please take the time to complete the following application and forward to Lauren Saunders at P. O. Box 1268, St. John’s, NL A1C 5M9; by fax at (709) 772-3266; or by e-mail at [email protected]. Proposed filming activities must meet certain conditions and receive the approval of the Field Unit Superintendent. Applications will be reviewed based on: potential impacts of the production on ecological and cultural resources appropriateness of activities to the national settings and regulations consistency with and contribution to park objectives, themes and messages level of disruption to the area and/or other park users required level of assistance and/or supervision by park staff Applicant Information Production Company Name: Project Name: Name, Address of authorized production representative: Telephone: Fax: e-mail: (Receipt of your application will be made by phone, fax or e-mail) Name of Producer: Designated Representative on Site: Filming/Photography - Requirements 1. How your production enhances the National Park/National Historic Site management 2. A list of other National Parks or National Historic Sites of Canada in which you have worked or propose to work 3. Location, date and time requirements 4. Production size (including cast, crew and drivers) 5. Type of equipment, sets and props and extent of use, including vehicles.Usage of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) at the sites in the Newfoundland East Field Unit requires Transport Canada permit along with special permission from the Field Unit Superintendent. -

National Park System Plan

National Park System Plan 39 38 10 9 37 36 26 8 11 15 16 6 7 25 17 24 28 23 5 21 1 12 3 22 35 34 29 c 27 30 32 4 18 20 2 13 14 19 c 33 31 19 a 19 b 29 b 29 a Introduction to Status of Planning for National Park System Plan Natural Regions Canadian HeritagePatrimoine canadien Parks Canada Parcs Canada Canada Introduction To protect for all time representa- The federal government is committed to tive natural areas of Canadian sig- implement the concept of sustainable de- nificance in a system of national parks, velopment. This concept holds that human to encourage public understanding, economic development must be compatible appreciation and enjoyment of this with the long-term maintenance of natural natural heritage so as to leave it ecosystems and life support processes. A unimpaired for future generations. strategy to implement sustainable develop- ment requires not only the careful manage- Parks Canada Objective ment of those lands, waters and resources for National Parks that are exploited to support our economy, but also the protection and presentation of our most important natural and cultural ar- eas. Protected areas contribute directly to the conservation of biological diversity and, therefore, to Canada's national strategy for the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity. Our system of national parks and national historic sites is one of the nation's - indeed the world's - greatest treasures. It also rep- resents a key resource for the tourism in- dustry in Canada, attracting both domestic and foreign visitors. -

Gros Morne National Park of Canada Management Plan, 2019

Management Plan Gros Morne 2019 National Park of Canada 2019 Gros Morne National Park of Canada A UNESCO World Heritage Site Management Plan ii © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Chief Executive Officer of Parks Canada, 2019. Gros Morne National Park of Canada Management Plan, 2019. Paper: R64-105/67-2019E 978-0-660-30733-6 PDF: R64-105/67-2019E-PDF 978-0-660-30732-9 Cette publication est aussi disponible en français. For more information about the management plan or about GROS MORNE NATIONAL PARK: GROS MORNE NATIONAL PARK PO Box 130 Rocky Harbour, NL A0K 4N0 Tel: 709-458-2417 Email: [email protected] www.pc.gc.ca/en/pn-np/nl/grosmorne Front cover image credits top from left to right: G. Paquette-Jetten/Parks Canada, D. Kennedy, S. Stone/Parks Canada, bottom: G. Paquette-Jetten/Parks Canada Gros Morne National Park iii Management Plan Foreword Canada’s national parks, national historic sites and national marine conservation areas belong to all Canadians and offer truly Canadian experiences. These special places make up one of the finest and most extensive systems of protected natural and cultural heritage areas in the world. The Government is committed to preserving our natural and cultural heritage, expanding the system of protected places and contributing to the recovery of species-at-risk. At the same time, we must continue to offer new and innovative visitor and outreach programs and activities so that more Canadians can experience Parks Canada places and learn about our environment, history and culture. -

Newfoundland and Labrador

Proudly Bringing You Canada At Its Best and and culture are woven into the tapestry of Canada’s history Land the Canadian spirit. The richness of our great country is cele- brated in a network of protected places that allow us to understand the land, people and events that shaped Canada. Some things just can’t be replaced and, therefore, your support is vital in protecting the ecological and commemorative integrity of these nat- ural areas and symbols of our past, so they will persist, intact and vibrant, into the future. Discover for yourself the many wonders, adventures and learning experiences that await you in Canada’s national parks, national historic sites, historic canals and national marine conservation areas, help us keep them healthy and whole for their sake, for our sake. Our Mission Parks Canada’s mission is to ensure that Canada’s national parks, nation- al historic sites and related heritage areas are protected and presented for this and future generations. These nationally significant examples of Canada’s natural and cultural heritage reflect Canadian values, identity, and pride. Contents Welcome......................................................................................................1 Terra Nova National Park of Canada.....................................................4 Terra Nova National Park of Canada Map ...........................................9 Castle Hill National Historic Site of Canada ........................................10 Signal Hill National Historic Site of Canada ........................................11 -

National Park System: a Screening Level Assessment

Environment Canada Parks Canada Environnement Canada Parcs Canada Edited by: Daniel Scott Adaptation & Impacts Research Group, Environment Canada and Roger Suffling School of Planning, University of Waterloo May 2000 Climate change and Canada’s national park system: A screening level assessment Le Changement climatique et le réseau des parcs nationaux du Canada : une évaluation préliminaire This report was prepared for Parks Canada, Department of Canadian Heritage by the Adaptation & Impacts Research Group, Environment Canada and the Faculty of Environmental Studies, University of Waterloo. The views expressed in the report are those of the study team and do not necessarily represent the opinions of Parks Canada or Environment Canada. Catalogue No.: En56-155/2000E ISBN: 0-662-28976-5 This publication is available in PDF format through the Adaptation and Impacts Research Group, Environment Canada web site < www1.tor.ec.gc.ca/airg > and available in Canada from the following Environment Canada office: Inquiry Centre 351 St. Joseph Boulevard Hull, Quebec K1A 0H3 Telephone: (819) 997-2800 or 1-800-668-6767 Fax: (819) 953-2225 Email: [email protected] i Climate change and Canada’s national park system: A screening level assessment Le Changement climatique et le réseau des parcs nationaux du Canada : une évaluation préliminaire Project Leads and Editors: Dr. Daniel Scott1 and Dr. Roger Suffling2 1 Adaptation and Impacts Research Group, Environment Canada c/o the Faculty of Environmental Studies, University of Waterloo Waterloo, Ontario N2L 3G1 519-888-4567 ext. 5497 [email protected] 2 School of Planning Faculty of Environmental Studies, University of Waterloo Waterloo, Ontario N2L 3G1 Research Team: Derek Armitage - Ph.D. -

ASFWB Fall AGM in Terra Nova National Park, Newfoundland

The Official Newsletter of the Atlantic Society of Fish and Wildlife Biologists VOLUME 51, ISSUE I April 2015 ASFWB Fall AGM in Terra Nova National Park, Newfoundland Left: Group shot before heading out on the field trip. Right: Student Award winners Louis Charron and Emily Kissler with president Mark Pulsifer (Photos: Kate Goodall) A small but mighty contingent topics including the impact of raised by the silent auction for of biologists headed to Terra moose on forests in the scholarship fund. Nova National Park in late Newfoundland, the perceptions The AGM ended off with a field October for the 51st ASFWB of nuisance wildlife among trip to Park Harbour, South Annual General Meeting. The farmers in Nova Scotia and Broad Cove, and Minchins event kicked off with a special New Brunswick, and the Cove. ice breaker hosted by Kirby. restoration of watershed Attendees were treated to local processes on Base Gagetown. A special thank you goes out to cuisine including cod Student award winners were everyone who participated, and “britches”, crab, moose, and Emilie Kissler who spoke on those involved in planning and snowshoe hare along with the impacts of moose on coordinating the event, some local beverages. The Newfoundland forests and especially Kirby Tulk. musical talents of many a Louis Charron who spoke on biologist were showcased well balsm fir forest restoration Stay tuned for more info on the into the wee hours of the following excessive moose 52nd AGM which will be in morning. browse. Nova Scotia next fall! The following day nine talks A fun time was had by all at were delivered on a variety of the banquet and $350 was Don’t miss this! Above: Chef Insects of Hypopagea 3 Kirby using a table saw as a Eelgrass Mapping 7 cooking surface, look out Gordon Ramsey! Profile: Bon Portage Island 17 (Photo: Kate Upcoming Events 21 Goodall) PAGE 2 BIOLINK VOLUME 51, ISSUE I The David J. -

Geocaching: Using Technology As a National Historic Site’S World Heritage Sirmilik and Ukkusiksalik Means to a Great Experience

parks canada agency Words to Action a p r i l 2 0 0 8 www.pc.gc.ca Cover Photos Background image (front and back): Kluane National Park and Reserve of Canada, J.F. Bergeron/ENVIROFOTO, 2000 Featured Images (left to right, top to bottom): Prince Albert National Park of Canada, W. Lynch, 1997; Gros Morne National Park of Canada, Michael Burzynski, 2001; Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Site of Canada, Chris Reardon, 2006; Parkdale Fire Station, Parks Canada Inside Cover Photo S. Munn, 2000 Amended (July, 2008) Words to Action Table of Contents INTRODUctiON . 1 PARKS CANADA’S RELAtiONShipS With FAciLitAtiNG ViSitOR EXPERIENCE . 39 ABORIGINAL PEOPLES . 23 Explorer Quotient: CONSERVAtiON OF Healing Broken Connections at Personalizing Visitor Experiences . .41 CULTURAL RESOURCES . 3 Kluane National Park and Making Personal Connections Hands-on History . 4 Reserve of Canada . 24 Through Interpretation . 43 Celebrating the Rideau Canal Inuit Knowledge at Auyuittuq, Geocaching: Using Technology as a National Historic Site’s World Heritage Sirmilik and Ukkusiksalik Means to a Great Experience . 45 National Parks of Canada . 25 Designation . 5 Planning for Great Visitor Experiences: Enhancing the System of National Employment Program: The Visitor Experience Assessment . 47 Enhancing Aboriginal Employment Historic Sites . 7 Opportunities . 26 A Role in the Lives of Today’s CONTActiNG PARKS CANADA . 49 Communities: Parkdale Fire Station . 10 Presentation of Aboriginal Themes: Aboriginal Interpretation Innovation Sahoyúé §ehdacho National Historic Fund . 27 Site of Canada: A Sacred Place . 11 Commemoration of Aboriginal History . 29 PROTEctiON OF NATURAL RESOURCES . 13 Establishing New National Parks OUTREAch EDUCAtiON . 31 and National Marine Conservation Areas . -

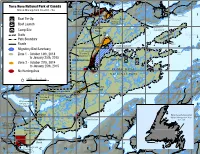

MMA Hunting Season 2014-2015 with Grid

Glovertown Culls Harbour Sandringham Northeast Arm Terra Nova National Park of Canada Traytown Moose Management Area NO. 28A UTM coordinate Eastport 280850m E 310 5392330m N Louil Hills Sandy Cove 1 UTM coordinate Boat Tie-Up Happy Adventure 284332m E 5393589m N North Broad Boat Launch Cove UTM coordinate Southwest 292018m E Camp Site Brook 5389506m N Blue d n nd Bonavista Trails Hill ou sla S le I a Bay 2 Park Boundary Sw an m Seal Roads ew Island UTM coordinate N 728437m E Migratory Bird Sanctuary UTM coordinate 5383551m N Hurloc Zone 1 - October 14th, 2014 718389m E Head to January 25th, 2015 5384104m N Park Administration Outport Trail 3 Zone 2 - October 27th, 2014 to January 25th, 2015 No Hunting Area TERRA NOVA N ATIONAL PARK N 0 0.5 1 2 3 4 km 301 4 UTM coordinate 718651m E oad Ochre Te rra ova R 5376068m N N Hill The Town of Gros Bog UTM coordinate Terra Nova 712135m E UTM coordinate 5375846m N 711112m E Sandy 5375089m N Pond UTM coordinate 710725m E 5 5369649m N UTM coordinate 708809m E 5368295m N Dunphys Clode Sound Terra Nova National Park Pond Moose Management Area Trail Charlottetown NO. 28A UTM coordinate 706207m E 6 5367663m N UTM coordinate 708677m E 5365780m N UTM coordinate Golf 706278m E Course Cobblers 5365786m N 0 25 50 100 Brook Kilometers UTM coordinate A B 708688m E C D E F G H I Port Blandford 5363679m N Terra Nova National Areas excluded to hunting FEDERAL AND PROVINCIAL MAP TERRAPark NOVA of Canada NATIONAL PARK Areas excluded to hunting include a 20 m buer around Hunters interested in obtaining topographic maps or aerial TerraAREA Nova NO.