National Park System Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saskatchewan Discovery Guide

saskatchewan discovery guide OFFICIAL VACATION AND ACCOMMODATION PLANNER CONTENTS 1 Contents Welcome.........................................................................................................................2 Need More Information? ...........................................................................................4 Saskatchewan Tourism Zones..................................................................................5 How to Use the Guide................................................................................................6 Saskatchewan at a Glance ........................................................................................9 Discover History • Culture • Urban Playgrounds • Nature .............................12 Outdoor Adventure Operators...............................................................................22 Regina..................................................................................................................... 40 Southern Saskatchewan.................................................................................... 76 Saskatoon .............................................................................................................. 158 Central Saskatchewan ....................................................................................... 194 Northern Saskatchewan.................................................................................... 276 Events Guide.............................................................................................................333 -

Department of Environment– Wildlife Division

Department of Environment– Wildlife Division Wildlife Research Section Department of Environment Box 209 Igloolik, NU X0A 0L0 Tel: (867) 934-2179 Fax: (867) 934-2190 Email: [email protected] Frequently Asked Questions Government of Nunavut 1. What is the role of the GN in issuing wildlife research permits? On June 1, 1999, Nunavut became Canada’s newest territory. Since its creation, interest in studying its natural resources has steadily risen. Human demands on animals and plants can leave them vulnerable, and wildlife research permits allow the Department to keep records of what, and how much research is going on in Nunavut, and to use this as a tool to assist in the conservation of its resources. The four primary purposes of research in Nunavut are: a. To help ensure that communities are informed of scientific research in and around their communities; b. To maintain a centralized knowledgebase of research activities in Nunavut; c. To ensure that there are no conflicting or competing research activities in Nunavut; and d. To ensure that wildlife research activities abide by various laws and regulations governing the treatment and management of wildlife and wildlife habitat in Nunavut. 2. How is this process supported by the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement? Conservation: Article 5.1.5 The principles of conservation are: a. the maintenance of the natural balance of ecological systems within the Nunavut Settlement Area; b. the protection of wildlife habitat; c. the maintenance of vital, healthy, wildlife populations capable of sustaining harvesting needs as defined in this article; and d. the restoration and revitalization of depleted populations of wildlife and wildlife habitat. -

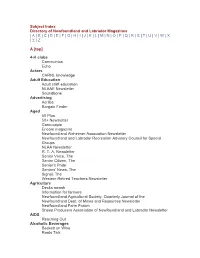

Subject Index Directory of Newfoundland and Labrador

Subject Index Directory of Newfoundland and Labrador Magazines | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z A [top] 4-H clubs Communico Echo Actors CARNL knowledge Adult Education Adult craft education NLAAE Newsletter Soundbone Advertising Ad libs Bargain Finder Aged 50 Plus 50+ Newsletter Cornucopia Encore magazine Newfoundland Alzheimer Association Newsletter Newfoundland and Labrador Recreation Advisory Council for Special Groups NLAA Newsletter R. T. A. Newsletter Senior Voice, The Senior Citizen, The Senior's Pride Seniors' News, The Signal, The Western Retired Teachers Newsletter Agriculture Decks awash Information for farmers Newfoundland Agricultural Society. Quarterly Journal of the Newfoundland Dept. of Mines and Resources Newsletter Newfoundland Farm Forum Sheep Producers Association of Newfoundland and Labrador Newsletter AIDS Reaching Out Alcoholic Beverages Beckett on Wine Roots Talk Winerack Alcoholism Alcoholism and Drug Addiction Foundation of Newfoundland and Labrador. Newsletter Banner of temperance Highlights Labrador Inuit Alcohol and Drug Abuse Program Alternate Alternate press Current Downtown Press Alumni Luminus OMA Bulletin Spencer Letter Alzheimer's disease Newfoundland Alzheimer Association Newsletter Anglican Church Angeles Avalon Battalion bugle Bishop's newsletter Diocesan magazine Newfoundland Churchman, The Parish Contact, The St. Thomas' Church Bulletin St. Martin's Bridge Trinity Curate West Coast Evangelist Animal Welfare Newfoundland Poney Care Inc. Newfoundland Pony Society Quarterly Newsletter SPCA Newspaws Aquaculture Aqua News Cod Farm News Newfoundland Aquaculture Association Archaeology Archaeology in Newfoundland & Labrador Avalon Chronicles From the Dig Marine Man Port au Choix National Historic Site Newsletter Rooms Update, The Architecture Goulds Historical Society. -

National Parks: Time to Burn (For Ecological Integrity’S Sake)

National Parks: Time to Burn (for Ecological Integrity’s Sake) By Andrea Johancsik, AWA Conservation Specialist tanding at the peak of the east end nities. In Alberta we saw the subsequent National Park this way in 1915. Eight de- of Rundle last month, my friends creation of Waterton Lakes National Park cades later, then- graduate student Jeanine S and I marveled at the sunny, spring in 1895, Elk Island National Park in 1906, Rhemtulla, Dr. Eric Higgs, and other mem- day we were fortunate enough to witness Jasper National Park in 1907, and Wood bers of the Mountain Legacy project pains- from 2,530m high. The hike gives vistas of Buffalo National Park in 1922. The high- takingly retook all 735 of Bridgland’s Jasper remote mountain peaks and forested slopes, ly popular and newly accessible mountain photos. They wanted to compare how the as well as the highly visible town of Can- parks became dominated by tourism and vegetation on the landscape had changed, more and the Spray Lakes dam. However, commercial development, roads, and re- if it had changed at all, over nearly a cen- arguably one of the biggest human-caused moval of keystone species like the plains tury. Their study found that vegetation has changes in the mountain national parks is bison. Many of the 3.6 million visitors who become less diverse and is now dominated much less obvious. Decades of fire suppres- passed through Banff National Park last year by closed-canopy coniferous forests; in 1915 sion have changed the landscape in a dra- probably didn’t realize they were looking at the landscape consisted of open coniferous matic way; had we been at the summit 80 a drastically different landscape from the one forest, grasslands, young forests and some years ago our view likely would have been of a century ago. -

The Effects of Linear Developments on Wildlife

Bibliography Rec# 5. LeBlanc, R. 1991. The aversive conditioning of a roadside habituated grizzly bear within Banff Park: progress report 1991. 6 pp. road impacts/ grizzly bear/ Ursus arctos/ Banff National Park/ aversive conditions/ Icefields Parkway. Rec# 10. Forman, R.T.T. 1983. Corridors in a landscape: their ecological structure and function. Ekologia 2 (4):375-87. corridors/ landscape/ width. Rec# 11. McLellan, B.N. 1989. Dymanics of a grizzly bear population during a period of industrial resource extraction. III Natality and rate of increase. Can. J. Zool. Vol. 67 :1865-1868. reproductive rate/ grizzly bear/ Ursus arctos/ British Columbia/ gas exploration/ timber harvest. Rec# 14. McLellan, B.N. 1989. Dynamics of a grizzly bear population during a period of industrial resource extraction. II.Mortality rates and causes of death. Can. J. Zool. Vol. 67 :1861-1864. British Columbia/ grizzly bear/ Ursus arctos/ mortality rate/ hunting/ outdoor recreation/ gas exploration/ timber harvest. Rec# 15. Miller, S.D., Schoen, J. 1993. The Brown Bear in Alaska . brown bear/ grizzly bear/ Ursus arctos middendorfi/ Ursus arctos horribilis/ population density/ distribution/ legal status/ human-bear interactions/ management/ education. Rec# 16. Archibald, W.R., Ellis, R., Hamilton, A.N. 1987. Responses of grizzly bears to logging truck traffic in the Kimsquit River valley, British Columbia. Int. Conf. Bear Res. and Manage. 7:251-7. grizzly bear/ Ursus / arctos/ roads/ traffic/ logging/ displacement/ disturbance/ carnivore/ BC/ individual disruption / habitat displacement / habitat disruption / social / filter-barrier. Rec# 20. Kasworm, W.F., Manley, T.L. 1990. Road and trail influences on grizzly bears and black bears in northwest Montana. -

Beautiful by Nature !

PRESS KIT Beautiful by Nature ! Bas-Saint-Laurent Gaspésie Côte-Nord Îles de la Madeleine ©Pietro Canali www.quebecmaritime.ca Explore Québec maritime… PRESENTATION 3 DID YOU KNOW THAT… 4 NATIONAL PARKS 5 WILDLIFE OBSERVATION 7 WINTER ACTIVITIES 8 UNUSUAL LODGING 10 GASTRONOMY 13 REGIONAL AMBASSADORS 17 EVENTS 22 STORY IDEAS 27 QUÉBEC MARITIME PHOTO LIBRARY 30 CONTACT AND SOCIAL MEDIA 31 Le Québec maritime 418 724-7889 84, Saint-Germain Est, bureau 205 418 724-7278 Rimouski (Québec) G5L 1A6 @ www.quebecmaritime.ca Presentation Located in Eastern Québec, Québec maritime is made up of the easternmost tourist regions in the province, which are united by the sea and a common tradition. These regions are Bas-Saint-Laurent, Gaspésie, Côte-Nord and the Îles de la Madeleine. A vast territory bordered by 3000 kilometres (1900 miles) of coastline, which alternates between wide fine- sand beaches and small, rocky bays or impressive cliffs, Québec maritime has a long tradition that has been shaped by the ever-present sea. This tradition is expressed in the lighthouses that dot the coast, diverse and abundant wildlife, colourfully painted houses, gatherings on the quays and especially the joie de vivre of local residents. There are places you have to see, feel and experience… Québec maritime is one of them! Did You Know That… The tallest lighthouse in Canada is in Cap-des-Rosiers and is 34 metres (112 feet) high? Jacques Cartier named the Lower North Shore “the land of many isles” because this region’s islands were too numerous to name individually? Lake Pohénégamook is said to hide a monster named Ponik? The Manicouagan impact crater is the fifth largest in the world and can be seen from space? Legendary Percé Rock had three arches in Jacques Cartier’s time? The award winning movie Seducing Dr. -

Fundy National Park

Fundy National Park New Brunswick Fundy Cover: Point Wolfe River with Point Wolfe in background View of McLaren Pond and Bay of Fundy Introducing a Park and an Idea blanket of rock debris called glacial till. It is from this Canada covers half a continent, fronts on three oceans, glacial till that most of the poor, stony soils of Fundy and stretches from the extreme Arctic more than half-way National Park have developed. National Park to the equator. A booklet describing the park's geology in more detail There is a great variety of land forms in this immense can be purchased at the park information office. country, and Canada's national parks have been created to preserve important examples for you and generations The Plants to come. The valleys and rounded hills of Fundy National Park The National Parks Act of 1930 specifies that national are covered with a varied vegetation, dominated by a parks are "dedicated to the people . for their benefit, mixture of broad-leaved and evergreen trees. education and enjoyment," and must remain "unimpaired Within the park are two forest zones. Along the coast, New Brunswick for the enjoyment of future generations." where summers are cool, yellow and white birch are Fundy National Park, 80 square miles in area, skirts scattered among red spruce and balsam fir. The warmer the Bay of Fundy for eight miles and extends inland for plateau is dominated on higher ground by stands of more than nine over a rolling, forested plateau. The sugar maple, beech, and yellow birch, while red spruce, park preserves a superb example of the Bay of Fundy's balsam fir, and red maple thrive in low, swampy areas. -

Bathurst Fact Sheet

Qausuittuq National Park Update on the national park proposal on Bathurst Island November 2012 Parks Canada, the Qikiqtani Inuit Association (QIA) and the community of Resolute Bay are working together to create a new national park on Bathurst Island, Nunavut. The purpose of the park is to protect an area within the The park will be managed in co-operation with Inuit for Western High Arctic natural region of the national park the benefit, education and enjoyment of all Canadians. system, to conserve wildlife and habitat, especially areas It is expected that the park’s establishment will enhance important to Peary caribou, and enable visitors to learn and support local employment and business as well as about the area and its importance to Inuit. help strengthen the local and regional economies. Qausuittuq National Park and neighbouring Polar Bear Within the park, Inuit will continue to exercise their Pass National Wildlife Area will together ensure protec - right to subsistence harvesting. tion of most of the northern half of Bathurst Island as well as protection of a number of smaller nearby islands. Bringing you Canada’s natural and historic treasures Did you know? After a local contest, the name of the proposed national park was selected as Qausuittuq National Park. Qausuittuq means “place where the sun does - n't rise” in Inuktitut, in reference to the fact that the sun stays below the horizon for several months in the winter at this latitude. What’s happening? Parks Canada and Qikiqtani Inuit Association (QIA) are working towards completion and rati - fication of an Inuit Impact and Benefit Agree - ment (IIBA). -

Biological Assessment on the Proposed Activities on Fort Drum

BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT on the PROPOSED ACTIVITIES ON FORT DRUM MILITARY INSTALLATION, FORT DRUM, NEW YORK (2015-2017) FOR THE INDIANA BAT (Myotis sodalis) and NORTHERN LONG-EARED BAT (Myotis septentrionalis) September 2014 Prepared By: U.S. Army Garrison Fort Drum Fish & Wildlife Management Program Environmental Division, Directorate of Public Works 2015-2017 FORT DRUM BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT FOR THE INDIANA AND NORTHERN LONG-EARED BAT TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures …………………………………………………………………… vi List of Tables ……………………………………………………………………. viii Executive Summary ……………………………………………………………………. ix 1.0 Background 1 1.1 Purpose ………………………………………………………………………... 1 1.2 Consultation History …..……………………………………………………… 1 1.3 Fort Drum Military Installation ……………………………………………….. 3 1.3.1 Regional Description of Fort Drum ……………………………….. 3 1.3.2 Military Mission & History ………………………………………….. 3 1.3.3 General Description of Fort Drum ……………………………….... 3 1.3.4 General Habitat Information on Fort Drum ……………………..... 3 1.4 Action Area ..………………………………………………………………….. 4 1.5 Indiana Bat ……………………………………………………………………. 7 1.5.1 General Description …………….………………………………….. 7 1.5.2 Distribution ………………………………………………………….. 7 1.5.3 Population Status …………………………………………………… 7 1.5.3.1 Rangewide and New York…………………………………. 7 1.5.3.2 Fort Drum……………………………………………………. 10 1.5.4 Background Ecology ……………………………………………….. 14 1.5.4.1 Hibernation ………..……………………………..…………. 14 1.5.4.2 Spring Emergence ….……………………………………… 14 1.5.4.3 Summer Roosting and Reproductive Behavior …………. 15 1.5.4.4 Foraging/Traveling Movements …………………………. 18 ….. …………………………… 1.5.4.5 Fall………. Swarming ……………………………………………… 22 1.6 Northern long-eared Bat …………………………………………………… 23 1.6.1 General Description………………………………………………... 23 1.6.2 Distribution ………………………………………………………….. 23 1.6.3 Population Status …………………………………………………… 24 1.6.3.1 Rangewide and New York…………………………………. 24 1.6.3.2 Fort Drum……………………………………………………. 24 1.6.4 Background Ecology ………………………………………………. -

Reclassifying the Wood Bison

6734 Federal Register / Vol. 76, No. 26 / Tuesday, February 8, 2011 / Proposed Rules input in person, by mail, e-mail, or January 13, 2011. generally means that we will post any phone at any time during the Peter J. Probasco, personal information you provide us rulemaking process. Acting Chair, Federal Subsistence Board. (see the Public Comments section below January 13, 2011. for more information). Executive Order 13211 Steve Kessler, FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: This Executive Order requires Subsistence Program Leader, USDA–Forest Marilyn Myers at U.S. Fish and Wildlife agencies to prepare Statements of Service. Service, Fisheries and Ecological Energy Effects when undertaking certain [FR Doc. 2011–2679 Filed 2–7–11; 8:45 am] Services, 1011 E. Tudor Road, actions. However, this proposed rule is BILLING CODE 3410–11–P; 4310–55–P Anchorage, Alaska 99503, or telephone not a significant regulatory action under 907–786–3559 or by facsimile at (907) E.O. 13211, affecting energy supply, 786–3848. If you use a distribution, or use, and no Statement of DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR telecommunications device for the deaf (TDD), please call the Federal Energy Effects is required. Fish and Wildlife Service Information Relay Service (FIRS) at Drafting Information 800–877–8339. 50 CFR Part 17 SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Theo Matuskowitz drafted these regulations under the guidance of Peter [Docket No. FWS–R9–IA–2008–0123; MO Public Comments 92210–1113FWDB B6] J. Probasco of the Office of Subsistence We intend that any final action Management, Alaska Regional Office, RIN 1018–AI83 resulting from this proposed rule will be U.S. -

Gros Morne National Park

DNA Barcode-based Assessment of Arthropod Diversity in Canada’s National Parks: Progress Report for Gros Morne National Park Report prepared by the Bio-Inventory and Collections Unit, Biodiversity Institute of Ontario, University of Guelph December 2014 1 The Biodiversity Institute of Ontario at the University of Guelph is an institute dedicated to the study of biodiversity at multiple levels of biological organization, with particular emphasis placed upon the study of biodiversity at the species level. Founded in 2007, BIO is the birthplace of the field of DNA barcoding, whereby short, standardized gene sequences are used to accelerate species discovery and identification. There are four units with complementary mandates that are housed within BIO and interact to further knowledge of biodiversity. www.biodiversity.uoguelph.ca Twitter handle @BIO_Outreach International Barcode of Life Project www.ibol.org Canadian Centre for DNA Barcoding www.ccdb.ca Barcode of Life Datasystems www.boldsystems.org BIObus www.biobus.ca Twitter handle @BIObus_Canada School Malaise Trap Program www.malaiseprogram.ca DNA Barcoding blog www.dna-barcoding.blogspot.ca International Barcode of Life Conference 2015 www.dnabarcodes2015.org 2 INTRODUCTION The Canadian National Parks (CNP) Malaise The CNP Malaise Program was initiated in 2012 Program, a collaboration between Parks Canada with the participation of 14 national parks in and the Biodiversity Institute of Ontario (BIO), Central and Western Canada. In 2013, an represents a first step toward the acquisition of additional 14 parks were involved, from Rouge detailed temporal and spatial information on National Urban Park to Terra Nova National terrestrial arthropod communities across Park (Figure 1). -

Entomological Opportunities in Grasslands National Park – an Invitation

Entomological opportunities in Grasslands National Park – an invitation Darcy C. Henderson Parks Canada, Western & Northern Service Center, 145 McDermot Avenue, Winnipeg MB, R3B 0R9 Beginning in summer 2006, two large-scale management experiments will begin in Grasslands National Park, both of which require long-term monitoring of many biological and environmen- tal indicators. The carefully planned experiments are designed to support future park management, and provide data suitable for scientific publica- tion. While the Park selected a few key indicators for staff to monitor, there were a number of other A rare blue form of the red-legged grasshopper, Melanoplus femurrubrum, found in Grasslands National Park. (photo by D.L. Johnson) indicators for which funds and time were simply not available. Not wanting to waste an opportu- nity for public participation and a chance to gain valuable information, Grasslands National Park is inviting professional and amateur entomologists to get involved in monitoring arthropods under several grazing and fire treatments planned for both the West and East Blocks of the Park (see map below; for an overview of the Park go to http: //www.pc.gc.ca/pn-np/sk/grasslands/index_e.asp). In the West Block, a combination of pre- scribed fire with short-duration, high-intensity livestock grazing will be implemented on na- tive mixed prairie and exotic crested wheatgrass vegetation between 2006 and 2007. The Park is primarily interested in the seed production re- sponse, because past experience indicates thrips (Thysanoptera) and possibly other insects damage much native seed in the ungrazed and unburned Upland grasslands dominated by needle and thread parts of the Park.