Biological Assessment on the Proposed Activities on Fort Drum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fundy National Park

Fundy National Park New Brunswick Fundy Cover: Point Wolfe River with Point Wolfe in background View of McLaren Pond and Bay of Fundy Introducing a Park and an Idea blanket of rock debris called glacial till. It is from this Canada covers half a continent, fronts on three oceans, glacial till that most of the poor, stony soils of Fundy and stretches from the extreme Arctic more than half-way National Park have developed. National Park to the equator. A booklet describing the park's geology in more detail There is a great variety of land forms in this immense can be purchased at the park information office. country, and Canada's national parks have been created to preserve important examples for you and generations The Plants to come. The valleys and rounded hills of Fundy National Park The National Parks Act of 1930 specifies that national are covered with a varied vegetation, dominated by a parks are "dedicated to the people . for their benefit, mixture of broad-leaved and evergreen trees. education and enjoyment," and must remain "unimpaired Within the park are two forest zones. Along the coast, New Brunswick for the enjoyment of future generations." where summers are cool, yellow and white birch are Fundy National Park, 80 square miles in area, skirts scattered among red spruce and balsam fir. The warmer the Bay of Fundy for eight miles and extends inland for plateau is dominated on higher ground by stands of more than nine over a rolling, forested plateau. The sugar maple, beech, and yellow birch, while red spruce, park preserves a superb example of the Bay of Fundy's balsam fir, and red maple thrive in low, swampy areas. -

National Park System Plan

National Park System Plan 39 38 10 9 37 36 26 8 11 15 16 6 7 25 17 24 28 23 5 21 1 12 3 22 35 34 29 c 27 30 32 4 18 20 2 13 14 19 c 33 31 19 a 19 b 29 b 29 a Introduction to Status of Planning for National Park System Plan Natural Regions Canadian HeritagePatrimoine canadien Parks Canada Parcs Canada Canada Introduction To protect for all time representa- The federal government is committed to tive natural areas of Canadian sig- implement the concept of sustainable de- nificance in a system of national parks, velopment. This concept holds that human to encourage public understanding, economic development must be compatible appreciation and enjoyment of this with the long-term maintenance of natural natural heritage so as to leave it ecosystems and life support processes. A unimpaired for future generations. strategy to implement sustainable develop- ment requires not only the careful manage- Parks Canada Objective ment of those lands, waters and resources for National Parks that are exploited to support our economy, but also the protection and presentation of our most important natural and cultural ar- eas. Protected areas contribute directly to the conservation of biological diversity and, therefore, to Canada's national strategy for the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity. Our system of national parks and national historic sites is one of the nation's - indeed the world's - greatest treasures. It also rep- resents a key resource for the tourism in- dustry in Canada, attracting both domestic and foreign visitors. -

Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction Du Branch Patrimoine De I'edition

DEFINING A FOREST REFERENCE CONDITION FOR KOUCHIBOUGUAC NATIONAL PARK AND ADJACENT LANDSCAPE IN EASTERN NEW BRUNSWICK USING FOUR RECONSTRUCTIVE APPROACHES by Donna R. Crossland BScH Biology, Acadia University, 1986 BEd, St Mary's University, 1990 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Forestry in the Graduate Academic Unit of Forestry and Environmental Management Supervisor: Judy Loo, PhD, Adjunct Professor of Forestry and Environmental Management/Ecological Geneticist, Canadian Forest Service, NRCan. Examining Board: Graham Forbes, PhD, Department of Forestry and Environmental Management, Chair Antony W. Diamond, PhD, Department of Biology This thesis is accepted. Dean of Graduate Studies THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW BRUNSWICK December 2006 © Donna Crossland, 2006 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-49667-1 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-49667-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. -

Caring for Canada

312-329_Ch12_F2 2/1/07 4:50 PM Page 312 CHAPTER 12 Caring for Canada hink of a natural area that is special to you. What if Tthere was a threat to your special place? What could you do? You might take positive steps as David Grassby did recently. David Grassby was 12 years old when he read an article about environmental threats to Oakbank Pond near his home in Thornhill, Ontario. David decided to help protect the pond and its wildlife. David talked to classmates and community members. He discovered that writing letters and informing the media are powerful tools to get action. He wrote many letters to the Town Council, the CBC, and newspapers. He appeared on several TV shows, including The Nature of Things hosted by David Suzuki. In each of his letters and interviews, David explained the problems facing the pond and suggested some solutions. For example, people were feeding the ducks. This attracted too many ducks for the pond to support. David recommended that the town install signs asking people not to feed the ducks. The media were able to convince people to make changes. David Grassby learned that it is important to be patient and to keep trying. He learned that one person can make a difference. Today, Oakbank Pond is a nature preserve, home to many birds such as ducks, Canada geese, blackbirds, and herons. It is a peaceful place that the community enjoys. 312 312-329_Ch12_F2 2/1/07 4:50 PM Page 313 Canada: Our Stories Continue What David Grassby did is an example of active citizenship. -

Fundy National Park 2011 Management Plan

Fundy National Park of Canada Management Plan NOVEMBER 2011 Fundy National Park of Canada Management Plan ii © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Chief Executive Officer of Parks Canada, 2011. Cette publication est aussi disponible en français. National Library of Canada cataloguing in publication data: Parks Canada Fundy National Park of Canada management plan [electronic resource]. Electronic monograph in PDF format. Issued also in French under the title: Parc national du Canada Fundy, plan directeur. Issued also in printed form. ISBN 978-1-100-13552-6 Cat. no.: R64-105/80-2010E-PDF 1. Fundy National Park (N.B.)—Management. 2. National parks and reserves—New Brunswick—Management. 3. National parks and reserves—Canada—Management. I. Title. FC2464 F85 P37 2010 971.5’31 C2009-980240-6 For more information about the management plan or about Fundy National Park of Canada: Fundy National Park of Canada P.O. Box 1001, Fundy National Park, Alma, New Brunswick Canada E4H 1B4 tel: 506-887-6000, fax: 506-887-6008 e-mail: [email protected] www.parkscanada.gc.ca/fundy Front Cover top images: Chris Reardon, 2009 bottom image: Chris Reardon, 2009 Fundy National Park of Canada iii Management Plan Foreword Canada’s national historic sites, national parks and national marine conservation areas are part of a century-strong Parks Canada network which provides Canadians and visitors from around the world with unique opportunities to experience and embrace our wonderful country. From our smallest national park to our most visited national historic site to our largest national marine conservation area, each of Canada’s treasured places offers many opportunities to enjoy Canada’s historic and natural heritage. -

Fundy Tourism MAP Final

Alpine Motor Inn World Class View Come experience the world’s highest tides as well as our historic fishing culture from the comfort of our ocean front accommodations. Alpine Motor Inn, 8591 Main Street, Alma, New Brunswick, E4H 1N5, Route 114 Phone: (506) 887-2052 | E-mail: [email protected]| Toll Free: 1 (866) 887-2052| Website: www.alpinemotorinn.ca Season: beginning of June to the middle of October 2021 Moosin’Moosin’ AroundAround GiftsGifts && ApparelApparel AlbertAlbert CountyCounty ClayClay Co.Co. “We’ve“We’ve GotGot TheThe LargestLargest SelectionSelection inin TheseThese Woods”Woods” Parkland Village Inn Drift with your Dreams... On the world’s highest tides. Panoramic oceanside accommodation at reasonable prices. Also enjoy Fundy’s finest seafood with us. Tides Restaurant is recommended in “Where to Eat in Canada” food guide. Parkland Village Inn & Tides Restaurant, 8601 Main Street, Alma, NB, E4H 1N6 Route 114, off route 1, exit 211 Phone: (506) 887 2313 Toll free: 1-866-668-4337 Free High -speed Internet Email: [email protected] Web site: www.parklandvillageinn.com Season: beginning of May to end of October Located in the heart of Alma, we have been providing Fundy visitors with gifts and apparel for 40 years and counting. BayBay ofof FundyFundy ClayClay Our unique sculptured pottery is a fusion of local raw clay with designs inspired by nature. 8591 Main Street, Alma, New Brunswick We make use of an abundant resource of natural clay within 10 km of the studio. Route 915 / 114 Phone: 1-506-887-2052 Studio -

National Parks, Monuments, and Historical Landmarks Visited

National Parks, Monuments, and Historical Landmarks Visited Abraham Lincoln Birthplace, KY Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, AZ Acadia National Park, ME Castillo de San Marcos, FL Adirondack Park Historical Landmark, NY Castle Clinton National Monument, NY Alibates Flint Quarries National Monument, TX Cedar Breaks National Monument, UT Agua Fria National Monument, AZ Central Park Historical Landmark, NY American Stock Exchange Historical Landmark, NY Chattahoochie River Recreation Area, GA Ancient Bristlecone Pine Forest, CA Chattanooga National Military Park, TN Angel Mounds Historical Landmark, IN Chichamauga National Military Park, TN Appalachian National Scenic Trail, NJ & NY Chimney Rock National Monument, CO Arkansan Post Memorial, AR Chiricahua National Monument, CO Arches National Park, UT Chrysler Building Historical Landmark, NY Assateague Island National Seashore, Berlin, MD Cole’s Hill Historical Landmark, MA Aztec Ruins National Monument, AZ Colorado National Monument, CO Badlands National Park, SD Congaree National Park, SC Bandelier National Monument, NM Constitution Historical Landmark, MA Banff National Park, AB, Canada Crater Lake National Park, OR Big Bend National Park, TX Craters of the Moon National Monument, ID Biscayne National Park, FL Cuyahoga Valley National Park, OH Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park, CO Death Valley National Park, CA & NV Blue Ridge, PW Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area, NJ & PA Bonneville Salt Flats, UT Denali (Mount McKinley) National Park. AK Boston Naval Shipyard Historical -

National Parks and National Historic Sites of Canada in New Brunswick

National Parks and National Historic Sites of Canada in New Brunswick Saint Croix Island International Historic Site Look inside for information on Kouchibouguac National Park, Fundy National Park and much more! Proudly Bringing You Canada At Its Best Land and culture are woven into the tapestry of Canada’s history and the Canadian spirit. The richness of our great country is celebrated in a network of protected places that allow us to understand the land, people and events that shaped Canada. Some things just can’t be replaced and, therefore, your support is vital in protecting the ecological and commemorative integrity of these natural areas and symbols of our past, so they will persist, intact and vibrant, into the future. Discover for yourself the many wonders, adventures and learning experiences that await you in Canada’s national parks, national historic sites, historic canals and national marine conservation areas. Help us keep them healthy and whole — for their sake, for our sake. Iceland Greenland U.S.A. Yukon Northwest Nunavut Territories British Newfoundland Columbia CCaannaaddaa and Labrador Alberta Manitoba Seattle Ontario Saskatchewan Quebec P.E.I. U.S.A. Nova Scotia New Brunswick Chicago New York Our Mission Parks Canada’s mission is to ensure that Canada’s national parks, national historic sites and related heritage areas are protected and presented for this and future generations. These nationally significant examples of Canada’s natural and cultural heritage reflect Canadian values, identity, and pride. 1 Welcome New Brunswick’s scenic beauty and abundant history will create lasting memories for you and your family. -

Geocaching: Using Technology As a National Historic Site’S World Heritage Sirmilik and Ukkusiksalik Means to a Great Experience

parks canada agency Words to Action a p r i l 2 0 0 8 www.pc.gc.ca Cover Photos Background image (front and back): Kluane National Park and Reserve of Canada, J.F. Bergeron/ENVIROFOTO, 2000 Featured Images (left to right, top to bottom): Prince Albert National Park of Canada, W. Lynch, 1997; Gros Morne National Park of Canada, Michael Burzynski, 2001; Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Site of Canada, Chris Reardon, 2006; Parkdale Fire Station, Parks Canada Inside Cover Photo S. Munn, 2000 Amended (July, 2008) Words to Action Table of Contents INTRODUctiON . 1 PARKS CANADA’S RELAtiONShipS With FAciLitAtiNG ViSitOR EXPERIENCE . 39 ABORIGINAL PEOPLES . 23 Explorer Quotient: CONSERVAtiON OF Healing Broken Connections at Personalizing Visitor Experiences . .41 CULTURAL RESOURCES . 3 Kluane National Park and Making Personal Connections Hands-on History . 4 Reserve of Canada . 24 Through Interpretation . 43 Celebrating the Rideau Canal Inuit Knowledge at Auyuittuq, Geocaching: Using Technology as a National Historic Site’s World Heritage Sirmilik and Ukkusiksalik Means to a Great Experience . 45 National Parks of Canada . 25 Designation . 5 Planning for Great Visitor Experiences: Enhancing the System of National Employment Program: The Visitor Experience Assessment . 47 Enhancing Aboriginal Employment Historic Sites . 7 Opportunities . 26 A Role in the Lives of Today’s CONTActiNG PARKS CANADA . 49 Communities: Parkdale Fire Station . 10 Presentation of Aboriginal Themes: Aboriginal Interpretation Innovation Sahoyúé §ehdacho National Historic Fund . 27 Site of Canada: A Sacred Place . 11 Commemoration of Aboriginal History . 29 PROTEctiON OF NATURAL RESOURCES . 13 Establishing New National Parks OUTREAch EDUCAtiON . 31 and National Marine Conservation Areas . -

The Bay of Fundy, with a Dash of Acadian Flavour

Capture your vacation memories by downloading the Keepmyvacation lite your app free or memories by visiting the website www.myphoto.album.com and gain bragging rights! Instagram / Facebook / Twitter The Bay of Fundy, with a dash of Acadian Flavour Day of arrival Anticipate your ARRIVAL into the exciting hub city of Moncton, New Brunswick. Take this opportunity to get settled into your new space, relax and visit your surroundings! Get some rest, because a few days of fun- filled learning opportunities await you! Day One The Bay of Fundy was Canada’s only finalist, one Wake up and start your day with breakfast and get some comfortable shoes on! You will of 28 worldwide locations then depart and travel to the cozy community competing to become one and town of Saint Martins, NB. Your learning adventures will begin at FUNDY TRAIL of the New 7 Wonders of with a guided tour that will leave you breathless as you take in the beauty of the bay. Nature.in 2011. The 100 You will have the opportunity to walk the beach and visit the Saint Martin Caves billion tones of water that (times may alternate with Fundy Trail visit according to tides). Your appetite will lead fill the bay twice daily, you to enjoy a great lunch, overlooking the Bay of Fundy. could fill the Grand Relax while travelling to FUNDY NATIONAL PARK for a guided educational tour. Canyon. The Bay is a Notice the difference in the Bay and the tides in only a few short hours. A treat awaits unique phenomenon, and you at Kelly’s Bake Shop, which you can enjoy en route to CAPE ENRAGE known world-wide as a ADVENTURES. -

Superintendents Biographies

Superintendents Biographies Waterton Lakes National Park This document contains the superintendents biographies written by Chris Morrison of Lethbridge and Waterton Park, Alberta, as a component of the 2015-2016 Waterton Lakes National Park History Project. 1. John George “Kootenai” Brown 1910 - 1914 page 1 2. Robert Cooper 1914 - 1919 page 3 3. Frederick E. Maunder 1919 page 5 4. George Ace Bevan 1919 - 1924 page 7 5. William David Cromarty 1925 - 1930 page 9 6. Herbert Knight 1924 - 1939 page 11 7. Charles King “Cap” LeCapelain 1939 - 1942 page 13 8. Herbert A. DeVeber 1942 - 1951 page 15 9. James H. Atkinson 1951 - 1957 page 17 10. Tony W. Pierce 1957 - 1961 page 19 11. Fred Browning 1961 - 1964 page 21 12. J. Al Pettis 1965 page 23 13. W. James Lunney 1966 - 1969 page 25 14. Thomas L. Ross 1969 - 1979 page 27 15. Dave Adie 1971 - 1973 page 29 16. Tom W. Smith 1973 - 1976 page 31 17. Jean Pilon 1976 - 1978 page 33 18. Tony Bull 1978 - 1981 page 35 19. Bernie Lieff 1981 - 1988 page 37 20. Charlie Zinkan 1988 - 1992 page 39 21. Merv Syroteuk 1992 - 1996 page 41 22. Ian Syme 1996 - 1997 page 43 23. Josie Weninger 1997 - 1999 page 45 24. Peter Lamb 1999 - 2004 page 47 25. Rod Blair 2005 - 2009 page 49 26. Dave McDonough 2009 - 2011 page 51 27. Ifan Thomas 2012 - present page 53 John George “Kootenai” Brown Forest Ranger in Charge 1910-1914 John George “Kootenai” Brown is often called Waterton’s first superintendent but his official title was “forest ranger in charge” when he was appointed in 1910 to supervise what was then called Kootenay Lakes Forest Park.1 Brown was hired on the recommendation of a member of Parliament because he knew the area well, was a long-time land owner within the reserve, and had 10 years in the district as fishery officer for the Department of Marine and Fisheries.2 As Alberta’s population grew,3 and the park was beginning to be discovered 4 by more people, the need to protect Photo: WLNP Archives natural resources and enforce regulations was essential. -

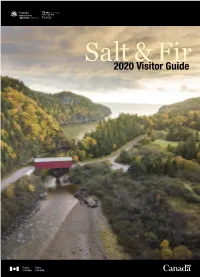

2020-Visitor-Guide-Salt-And-Fir.Pdf

Salt2020 & Visitor Fir Guide How to Reach Us Fundy National Park 8642 Highway # 114 Fundy National Park, NB E4H 4V2 Mailing Address: Fundy National Park P.O Box 1001 Alma, NB E4H 1B4 Tel: 506-887-6000 Fax: 506-887-6008 Email: [email protected] www.pc.gc.ca/fundy Parks Canada Reservation Service 1-877-737-3783 www.reservation.pc.gc.ca Welcome to Fundy National Park Your Bay of Fundy adventure starts here! Follow us FundyNP Welcome to Fundy National Park, a special protected piece of Canada’s coastal wilderness. Parks Canada manages sites in the Province of New Brunswick that are, since time immemorial, the traditional territories of @FundyNP the Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqiyik, and Peskotomuhkati peoples. This year, we are delighted to announce the opening of our newly Parks.Canada rebuilt Amphitheatre. This modern outdoor theatre is the ideal venue for enjoying our exciting programs including the 10th annual Rising Tide Emergency Numbers Festival in late August which plays host to the best musical talent the East Coast has to offer. Police, fire, ambulance: 911 Parks Canada visitor safety emergencies: After a year of work, the entirely new and ecologically sustainable 1-877-852-3100 Goose River Trail is now open. With its stunning views, this trail will quickly be recognized as one of Atlantic Canada’s premium coastal hiking Medical Centres and Services and biking experiences. Also, trail lovers of all types will delight in the First Aid: visit any campground kiosk or endless networks of multi-use trails in the Chignecto Recreation Area.