Conservation Advice Conostylis Micrantha Small Flowered Conostylis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cunninghamia Date of Publication: February 2020 a Journal of Plant Ecology for Eastern Australia

Cunninghamia Date of Publication: February 2020 A journal of plant ecology for eastern Australia ISSN 0727- 9620 (print) • ISSN 2200 - 405X (Online) The Australian paintings of Marianne North, 1880–1881: landscapes ‘doomed shortly to disappear’ John Leslie Dowe Australian Tropical Herbarium, James Cook University, Smithfield, Qld 4878 AUSTRALIA. [email protected] Abstract: The 80 paintings of Australian flora, fauna and landscapes by English artist Marianne North (1830-1890), completed during her travels in 1880–1881, provide a record of the Australian environment rarely presented by artists at that time. In the words of her mentor Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker, director of Kew Gardens, North’s objective was to capture landscapes that were ‘doomed shortly to disappear before the axe and the forest fires, the plough and the flock, or the ever advancing settler or colonist’. In addition to her paintings, North wrote books recollecting her travels, in which she presented her observations and explained the relevance of her paintings, within the principles of a ‘Darwinian vision,’ and inevitable and rapid environmental change. By examining her paintings and writings together, North’s works provide a documented narrative of the state of the Australian environment in the late nineteenth- century, filtered through the themes of personal botanical discovery, colonial expansion and British imperialism. Cunninghamia (2020) 20: 001–033 doi: 10.7751/cunninghamia.2020.20.001 Cunninghamia: a journal of plant ecology for eastern Australia © 2020 Royal Botanic Gardens and Domain Trust www.rbgsyd.nsw.gov.au/science/Scientific_publications/cunninghamia 2 Cunninghamia 20: 2020 John Dowe, Australian paintings of Marianne North, 1880–1881 Introduction The Marianne North Gallery in the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew houses 832 oil paintings which Marianne North (b. -

5.3.1 Flora and Vegetation

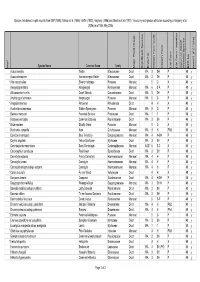

Flora and fauna assessment for the Calingiri study area Prepared for Muchea to Wubin Integrated Project Team (Main Roads WA, Jacobs and Arup) 5.3 FIELD SURVEY 5.3.1 Flora and vegetation A total of 296 plant taxa (including subspecies and varieties) representing 154 genera and 55 families were recorded in the study area. This total is comprised of 244 (82.4%) native species and 52 (17.6%) introduced (weed) species, and included 60 annual, 223 perennial species, one species that is known to be either annual or perennial and 12 unknown life cycles (Appendix 8). The current survey recorded a similar number of species to previous flora surveys conducted along GNH and higher average diversity (average number of taxa per km) (Table 5-7). Table 5-7 Comparison of floristic data from the current survey with previous flora surveys of GNH between Muchea and Wubin Survey Road Vegetation Taxa Av. taxa Families Genera Weeds length types (no.) per km (no.) (no.) (no.) (km) (no.) Current survey 19 25 296 16 55 154 52 Worley Parsons (2013) 21 12 197 9 48 114 29 ENV (ENV 2007) 25 18 357 14 59 171 44 Western Botanical (2006) 68 34 316 5 52 138 26 Ninox Wildlife Consulting (1989) 217 19 300 1 59 108 40 The most prominent families recorded in the study area were Poaceae, Fabaceae, Proteaceae, Myrtaceae, Asteraceae and Iridaceae (Table 5-8). The dominant families recorded were also prominent in at least some of the previous flora surveys. Table 5-8 Comparison of total number of species per family from the current survey with previous flora surveys Family Current survey Worley Parsons ENV (2007) Western Botanical Ninox Wildlife (2013) (2006) Consulting (1989) Poaceae 40 N/A1 42 4 15 Fabaceae 36 31 50 64 60 Proteaceae 30 N/A1 38 48 43 Myrtaceae 23 30 29 64 40 Asteraceae 19 N/A1 22 5 7 Iridaceae 14 N/A1 6 3 - 1 data not available. -

Flora and Vegetation Survey of the Proposed Kwinana to Australind Gas

__________________________________________________________________________________ FLORA AND VEGETATION SURVEY OF THE PROPOSED KWINANA TO AUSTRALIND GAS PIPELINE INFRASTRUCTURE CORRIDOR Prepared for: Bowman Bishaw Gorham and Department of Mineral and Petroleum Resources Prepared by: Mattiske Consulting Pty Ltd November 2003 MATTISKE CONSULTING PTY LTD DRD0301/039/03 __________________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1. SUMMARY............................................................................................................................................... 1 2. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 2 2.1 Location................................................................................................................................................. 2 2.2 Climate .................................................................................................................................................. 2 2.3 Vegetation.............................................................................................................................................. 3 2.4 Declared Rare and Priority Flora......................................................................................................... 3 2.5 Local and Regional Significance........................................................................................................... 5 2.6 Threatened -

BFS048 Site Species List

Species lists based on plot records from DEP (1996), Gibson et al. (1994), Griffin (1993), Keighery (1996) and Weston et al. (1992). Taxonomy and species attributes according to Keighery et al. (2006) as of 16th May 2005. Species Name Common Name Family Major Plant Group Significant Species Endemic Growth Form Code Growth Form Life Form Life Form - aquatics Common SSCP Wetland Species BFS No kens01 (FCT23a) Wd? Acacia sessilis Wattle Mimosaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Acacia stenoptera Narrow-winged Wattle Mimosaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y * Aira caryophyllea Silvery Hairgrass Poaceae Monocot 5 G A 48 y Alexgeorgea nitens Alexgeorgea Restionaceae Monocot WA 6 S-R P 48 y Allocasuarina humilis Dwarf Sheoak Casuarinaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Amphipogon turbinatus Amphipogon Poaceae Monocot WA 5 G P 48 y * Anagallis arvensis Pimpernel Primulaceae Dicot 4 H A 48 y Austrostipa compressa Golden Speargrass Poaceae Monocot WA 5 G P 48 y Banksia menziesii Firewood Banksia Proteaceae Dicot WA 1 T P 48 y Bossiaea eriocarpa Common Bossiaea Papilionaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y * Briza maxima Blowfly Grass Poaceae Monocot 5 G A 48 y Burchardia congesta Kara Colchicaceae Monocot WA 4 H PAB 48 y Calectasia narragara Blue Tinsel Lily Dasypogonaceae Monocot WA 4 H-SH P 48 y Calytrix angulata Yellow Starflower Myrtaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Centrolepis drummondiana Sand Centrolepis Centrolepidaceae Monocot AUST 6 S-C A 48 y Conostephium pendulum Pearlflower Epacridaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Conostylis aculeata Prickly Conostylis Haemodoraceae Monocot WA 4 H P 48 y Conostylis juncea Conostylis Haemodoraceae Monocot WA 4 H P 48 y Conostylis setigera subsp. -

Darwinia Hortiorum (Myrtaceae: Chamelaucieae), a New Species from the Darling Range, Western Australia

K.R.Nuytsia Thiele, 20: 277–281 Darwinia (2010) hortiorum (Myrtaceae: Chamelaucieae), a new species 277 Darwinia hortiorum (Myrtaceae: Chamelaucieae), a new species from the Darling Range, Western Australia Kevin R. Thiele Western Australian Herbarium, Department of Environment and Conservation, Locked Bag 104, Bentley Delivery Centre, Western Australia 6983 Email: [email protected] Abstract Thiele, K.R. Darwinia hortiorum (Myrtaceae: Chamelaucieae), a new species from the Darling Range, Western Australia. Nuytsia 20: 277–281 (2010). The distinctive, new, rare species Darwinia hortiorum is described, illustrated and discussed. Uniquely in the genus it has strongly curved- zygomorphic flowers with the sigmoid styles arranged so that they group towards the centre of the head-like inflorescences. Introduction Darwinia Rudge comprises c. 90 species, mostly from the south-west of Western Australia with c. 15 species in New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia. Phylogenetic analyses (M. Barrett, unpublished) have shown that the genus is polyphyletic, with distinct eastern and western Australian clades. Along with the related genera Actinodium Schauer, Chamelaucium Desf., Homoranthus A.Cunn. ex Schauer and Pileanthus Labill., the Darwinia clades are nested in a paraphyletic Verticordia DC. Many undescribed species of Darwinia are known in Western Australia, and these are being progressively described (Rye 1983; Marchant & Keighery 1980; Marchant 1984; Keighery & Marchant 2002; Keighery 2009). A significant number of taxa in the genus are narrowly endemic or rare and are of high conservation significance. Although taxonomic reassignment of the Western Australian species of Darwinia may be required in the future, resolving the status of these undescribed species and describing them under their current genus helps provide information for conservation assessments and survey. -

Supporting Information Appendix Pliocene Reversal of Late Neogene

1 Supporting Information Appendix 2 Pliocene reversal of late Neogene aridification 3 4 J.M.K. Sniderman, J. Woodhead, J. Hellstrom, G.J. Jordan, R.N. Drysdale, J.J. Tyler, N. 5 Porch 6 7 8 SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS AND METHODS 9 10 Pollen analysis. We attempted to extract fossil pollen from 81 speleothems collected from 11 16 caves from the Western Australian portion of the Nullarbor Plain. Nullarbor speleothems 12 and caves are essentially “fossil” features that appear to have been preserved by very slow 13 rates of landscape change in a semi-arid landscape. Sample collection targeted fallen, well 14 preserved speleothems in multiple caves. U-Pb dates of these speleothems (Table S3) 15 ranged from late Miocene (8.19 Ma) to Middle Pleistocene (0.41 Ma), with an average age 16 of 4.11 Ma. 17 Fossil pollen typically is present in speleothems in very low concentrations, so pollen 18 processing techniques were developed to minimize contamination by modern pollen (1), but 19 also to maximize recovery, to accommodate the highly variable organic matter content of the 20 speleothems, and to remove a clay- to fine silt-sized mineral fraction present in many 21 samples, which was resistant to cold HF and which can become electrostatically attracted to 22 pollen grains, inhibiting their identification. Stalagmite and flowstone samples of 30-200 g 23 mass were first cut on a diamond rock saw in order to remove any obviously porous material. 24 All subsequent physical and chemical processes were carried out within a HEPA-filtered 25 exhausting clean air cabinet in an ISO Class 7 clean room. -

Wildflower Society of Western Australia Newsletter Australian Native Plants Society (Australia), W

Wildflower Society of Western Australia Newsletter Australian Native Plants Society (Australia), W. A. Region ISSN 2207- 6204 February 2019 Vol. 57 No. 1 Price $4.00 Published quarterly. Registered by Australia Post. Publication No. 639699-00049 Ask for our seed packets at garden centres, nurseries, botanic gardens and souvenir shops or visit our website to see our range and extensive growing advice. Many Australian native plants require smoke to germinate their seeds. Our Wildflower Seed Starter granules are impregnated with smoke. Simple instructions on the packet. Suitable for all our packaged seed. Safe to handle. Phone: (08) 9470 6996 wildflowersofaustralia.com.au Wildflower Society of WA Newsletter, February 2019 1 WILDFLOWER SOCIETY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA The newsletter is published quarterly in February, May, August and November by the Wildflower Society of WA (Inc). Editor Committee convener and layout: Bronwen Keighery Contents Mail: PO Box 519 Floreat 6014 From the President 3 E-mail: [email protected] Management AGM 2019 Annoucements 4 New and rejoining Members 6 Deadline for the May issue is Events 2019 7 5 April 2019. Northern Suburbs – Annual Plant Sale 7 Landsdale Farm 7 Articles are the copyright of their authors. Branch Contacts and Meeting Details 7 In most cases permission to reprint articles Armadale Branch 9 Eastern Hill Branch 10 in not-for-profit publications can be Unusual branching in Xanthorrhoea 12 obtained from the author without charge, These People Really Care!!!! 12 on request. On death - and resurrection 16 Senecio One More One Less 23 The views and opinions expressed in the Who can explain it? 28 articles in this Newsletter are those of the Northern Suburbs Branch 28 Facebook Page Membership 29 authors and do not necessarily reflect those ANPSA Blooming Biodiversity Pre and Post of the Wildflower Society of WA (Inc.). -

Kew Science Publications for the Academic Year 2017–18

KEW SCIENCE PUBLICATIONS FOR THE ACADEMIC YEAR 2017–18 FOR THE ACADEMIC Kew Science Publications kew.org For the academic year 2017–18 ¥ Z i 9E ' ' . -,i,c-"'.'f'l] Foreword Kew’s mission is to be a global resource in We present these publications under the four plant and fungal knowledge. Kew currently has key questions set out in Kew’s Science Strategy over 300 scientists undertaking collection- 2015–2020: based research and collaborating with more than 400 organisations in over 100 countries What plants and fungi occur to deliver this mission. The knowledge obtained 1 on Earth and how is this from this research is disseminated in a number diversity distributed? p2 of different ways from annual reports (e.g. stateoftheworldsplants.org) and web-based What drivers and processes portals (e.g. plantsoftheworldonline.org) to 2 underpin global plant and academic papers. fungal diversity? p32 In the academic year 2017-2018, Kew scientists, in collaboration with numerous What plant and fungal diversity is national and international research partners, 3 under threat and what needs to be published 358 papers in international peer conserved to provide resilience reviewed journals and books. Here we bring to global change? p54 together the abstracts of some of these papers. Due to space constraints we have Which plants and fungi contribute to included only those which are led by a Kew 4 important ecosystem services, scientist; a full list of publications, however, can sustainable livelihoods and natural be found at kew.org/publications capital and how do we manage them? p72 * Indicates Kew staff or research associate authors. -

Guide for Preconference Tour Perth

GUIDE FOR PRECONFERENCE TOUR PERTH - GERALDTON 28 AUGUST 1988 @ ECOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF AUSTRALIA 1 AUSTRALIAN ECOSYSTEMS: 200 YEARS OF UTILISATION, DEGRADATION AND RECONSTRUCTION BIENNIAL SYMPOSIUM - GERALDTON, WESTERN AUSTRALIA 28 AUGUST - 2 SEPTEMBER 1988 PRE-CONFERENCE FIELD TRIP Angas Hopkins, Ted Griffin, David Bell & John Dell TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION • ....•.........•••.•••••••.•.•••••••••...•.•.•..••..... 2 CL IMA TE . ••••.•.•...•.•••..••••••••••••••••••••••••.••••..••.•••••.• 2 GEOLOGY • •••••.•••••••••..•••••••••••••••••••.••••••••••••..•••••••. 2 BIOGEOGRAPHY AND VEGETATION ..•.•.•...•••••..••...•.•....•......••.. 5 BOTANICAL HISTORY . ...........••••••••••••••.•...•...•••.••..•..•... 7 HUMA.N OCCUPATION .••....•.....•••••••••••••••••..•..••.•••••.•.•••.. 8 TUART WOODLANDS - YANCHEP NATIONAL PARK •••••..•....••.•••..•••.•.. 10 BANKSIA WOODLANDS - MOORE RIVER NATIONAL PARK •..••.•••••••.••.•••. 11 GINGIN SHIRE- CEt1ETERY . ..•.•..•••••••••••••••.•.•••••••••.......•.. 12 BANKSIA WOODLAND FAUNA •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 12 STREAMSIDE WOODLAND - REGAN'S FORD •••••••••.••••••••••.•.•••...•.. 13 BADGINGARRA NATIONAL PARK ••..••••••••.•••••••...••.••••••••..•.•.• 14 WOODLAND AND SHRUBLANDS - COOMALOO CREEK •••••••••••••••••••••.•••. 14 WOODLAND FAUNA . ••.•.•••.•.•••••••••••••••••••••••.••••••.•••••.•• • 16 ENEABBA KWONGAN - SAND MINING OPERATIONS ••••••••••••••••.•••.•••.. 16 GREENOUGH HISTORICAL VILLAGE •••••••••••..•••.•••••••••••.•••••••.. 18 REFERENCES • •••••..•.••••.••.•.•••••.•••..•••.••..••••••....••••••. -

Low Flammability Local Native Species (Complete List)

Indicative List of Low Flammability Plants – All local native species – Shire of Serpentine Jarrahdale – May 2010 Low flammability local native species (complete list) Location key – preferred soil types for local native species Location Soil type Comments P Pinjarra Plain Beermullah, Guildford and Serpentine River soils Alluvial soils, fertile clays and loams; usually flat deposits carried down from the scarp Natural vegetation is typical of wetlands, with sheoaks and paperbarks, or marri and flooded gum woodlands, or shrublands, herblands or sedgelands B Bassendean Dunes Bassendean sands, Southern River and Bassendean swamps Pale grey-yellow sand, infertile, often acidic, lacking in organic matter Natural vegetation is banksia woodland with woollybush, or woodlands of paperbarks, flooded gum, marri and banksia in swamps F Foothills Forrestfield soils (Ridge Hill Shelf) Sand and gravel Natural vegetation is woodland of jarrah and marri on gravel, with banksias, sheoaks and woody pear on sand S Darling Scarp Clay-gravels, compacted hard in summer, moist in winter, prone to erosion on steep slopes Natural vegetation on shallow soils is shrublands, on deeper soils is woodland of jarrah, marri, wandoo and flooded gum D Darling Plateau Clay-gravels, compacted hard in summer, moist in winter Natural vegetation on laterite (gravel) is woodland or forest of jarrah and marri with banksia and snottygobble, on granite outcrops is woodland, shrubland or herbs, in valleys is forests of jarrah, marri, yarri and flooded gum with banksia Flammability -

Floristics of the Banksia Woodlands on the Wallingup Plain in Relation to Environmental Parameters

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses : Honours Theses 2003 Floristics of the banksia woodlands on the Wallingup Plain in relation to environmental parameters Claire McCamish Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons Part of the Environmental Monitoring Commons Recommended Citation McCamish, C. (2003). Floristics of the banksia woodlands on the Wallingup Plain in relation to environmental parameters. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/359 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/359 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. -

City of Swan

418500mE 419000mE 419500mE 420000mE 420500mE 421000mE LEGEND WOODLANDS AND FORESTS W6: Woodland of Eucalyptus marginata , Corymbia calophylla and Eucalyptus wandoo over Low Open Woodland of Banksia grandis over Tall Open Shrubland of Xanthorrhoea preissii over Low Shrubland dominated by Hibbertia hypericoides and Dryandra lindleyana on sandy-gravel with lateritic outcropping M2 6490000mN W8: Woodland of Corymbia calophylla and Eucalyptus wandoo over Low Open Woodland of Melaleuca preissiana and Melaleuca viminea subsp. viminea over Shrubland of Calothamnus quadrifidus , W13 M2 Xanthorrhoea preissii and Acacia saligna over Very Open Sedgeland of W13 Schoenus subfascicularis on sand near creekline W9: Woodland of Eucalyptus wandoo over Open Heath dominated W6 by Hakea erinacea over Low Open Shrubland dominated by Hibbertia hypericoides on sandy clay W10: Open Forest of Corymbia calophylla and Eucalyptus wandoo M2 over Open Shrubland of Xanthorrhoea preissii over Low Shrubland dominated by Hakea lissocarpha and Dryandra lindleyana on sandy-clay W13 M2 W11: Woodland of Corymbia calophylla, Eucalyptus marginata and M2 occasional Eucalyptus wandoo over an Open Heath dominated by Xanthorrhoea preissii over Low Shrubland dominated by mixed species M2 including Hibbertia hypericoides and Tetraria octandra on sandy-loam W13 M2 W12: Woodland of Corymbia calophylla and Eucalyptus wandoo over 6489500mN Open Heath dominated by Calothamnus quadrifidus and Trymalium ledifolium over Low Shrubland of mixed species on sandy-loam W13 W13: Woodland of Eucalyptus