Baseline Information and Status Assessment of the Pallas's Cat in Iran

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Photographic Evidence of Desert Cat Felis Silvestris Ornata and Caracal

[VOLUME 5 I ISSUE 4 I OCT. – DEC. 2018] e ISSN 2348 –1269, Print ISSN 2349-5138 http://ijrar.com/ Cosmos Impact Factor 4.236 Photographic evidence of Desert cat Felis silvestris ornata and Caracal Felis caracal using camera traps in human dominated forests of Ranthambhore Tiger Reserve, Rajasthan, India Raju Lal Gurjar* & Anil Kumar Chhangani Department of Environmental Science, Maharaja Ganga Singh University, Bikaner- 334001 (Rajasthan) *Email: [email protected] Received: July 04, 2018 Accepted: August 22, 2018 ABSTRACT We recorded movement of Desert cat Felis silvestris ornata and Caracal Felis caracal using camera traps in human dominated corridors from Ranthambhore National Park to Kailadevi Wildlife Sanctuary, Western India. We obtained 9 caracal captures and one Desert cat capture in 360 camera trap nights. Our findings revels that presence of both cat species outside park in corridors was associated with functionality of corridor as well as availability of prey. Further the forest patches, ravines and undulating terrain supports dispersal of small mammals too. Desert cat and Caracals were more active late at night and during crepuscular hours. There was a difference in their activity between dusk and dawn. Since this is its kind of observation beyond parks regime we genuinely argue for conservation of corridors and its protection leads us to conserve both large as well as small cats in the region. Keywords: Desert Cat, Caracal, Camera Trap, Ranthambhore National Park, Kailadevi Wildlife Sanctuary INTRODUCTION India has 11 species of small cats besides the charismatic big cats like tiger Panthera tigris, leopard Panthera pardus, Snow leopard Panthera uncia and Asiatic lion Panthera leo persica. -

Curriculum Vita Gholamreza Mowlavi

Curriculum Vita Gholamreza Mowlavi Professor of Parasitology Department of Medical Parasitology & Mycology, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences P.O. Box: 14155-6446, Tehran, Iran Office Phone: +98 21 88951408 Fax: +98 21 88951392 Cell phone: +98 912 2080220 Email: [email protected] / [email protected]/ [email protected] Date of birth: 11 Sep 1960 Education Ph.D. Medical Parasitology, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, July 2004 RESEARCH INTEREST - Helminthes in tissue sections - Small mammal helminthes and Zoonosis - Palaeoparasitology (http://www.saltmen-iran.com) - Wildlife Parasitology 1 Courses Taught - Medical Helminthology for the students of Medicine, Pharmacy and Dentistry - Advanced Helminthology for the M.S. students of Parasitology - Identification of Helminthes in Tissue Sections for PhD students of Medical Parasitology - Laboratory Animals for the post graduate students of Medical Sciences Researches Done - Echinococcusis and Hydatidosis in North of Iran.(1996 – 2000 ) - Helminthic Fauna on Carnivores in Iran.(1996 – 2002 ) - Investigation on the Causes of Death Among Migratory Crane Birds.(2000 ) - Histopathological Study of Human Placentas in northwestern and southern Iran from the perspective of parasitology.(2001 – 2002 ) - Intestinal Parasites amongst Isfahan Municipality workers .(1977 -1978 ) - Isolation and Maintenance of Trypanosome lewisi in Laboratory Rat and In- vitro conditions. ( 2000 ) - Histopathology and Microanatomy of helminthes in human and animal tissues.( 2002 – 2004 -

Small Carnivores in Tinjure-Milke-Jaljale, Eastern Nepal

SMALL CARNIVORES IN TINJURE-MILKE-JALJALE, EASTERN NEPAL The content of this booklet can be used freely with permission for any conservation and education purpose. However we would be extremely happy to get a hard copy or soft copy of the document you have used it for. For further information: Friends of Nature Kathmandu, Nepal P.O. Box: 23491 Email: [email protected], Website: www.fonnepal.org Facebook: www.facebook.com/fonnepal2005 First Published: April, 2018 Photographs: Friends of Nature (FON), Jeevan Rai, Zaharil Dzulkafly, www.pixabay/ werner22brigitte Design: Roshan Bhandari Financial support: Rufford Small Grants, UK Authors: Jeevan Rai, Kaushal Yadav, Yadav Ghimirey, Som GC, Raju Acharya, Kamal Thapa, Laxman Prasad Poudyal and Nitesh Singh ISBN: 978-9937-0-4059-4 Acknowledgements: We are grateful to Zaharil Dzulkafly for his photographs of Marbled Cat, and Andrew Hamilton and Wildscreen for helping us get them. We are grateful to www.pixabay/werner22brigitte for giving us Binturong’s photograph. We thank Bidhan Adhikary, Thomas Robertson, and Humayra Mahmud for reviewing and providing their valuable suggestions. Preferred Citation: Rai, J., Yadav, K., Ghimirey, Y., GC, S., Acharya, R., Thapa, K., Poudyal, L.P., and Singh, N. 2018. Small Carnivores in Tinjure-Milke-Jaljale, Eastern Nepal. Friends of Nature, Nepal and Rufford Small Grants, UK. Small Carnivores in Tinjure-Milke-Jaljale, Eastern Nepal Why Protect Small Carnivores! Small carnivores are an integral part of our ecosystem. Except for a few charismatic species such as Red Panda, a general lack of research and conservation has created an information gap about them. I am optimistic that this booklet will, in a small way, be the starting journey of filling these gaps in our knowledge bank of small carnivore in Nepal. -

Feline Conservation Federation May/June 2011 • Volume 55, Issue 3 T ABLE Ofcontents Features MAY/JUNE 2011 | VOLUME 55, ISSUE 3

Feline Conservation Federation May/June 2011 • Volume 55, Issue 3 T ABLE OFcontents Features MAY/JUNE 2011 | VOLUME 55, ISSUE 3 Great Art for a Great Cause 15 Ocelot cub portrait by Jessica Kale to go to the highest bidder. 17 Make Fundraising Music with the FCF Let J.W. Everitt make your next event sing! 21 Initial Steps Toward Bigger & Greater Dreams Wildlife educators course and top-level exhibitors help prepare Craig DeRosa for his future. Stewie the Serval: Supercat! 25 Jackie Adebahr introduces us to a beloved member of her family. 30 Small Cat Populations Decimated in the Kẻ Gỗ-Khê Nét Lowlands, Central Vietnam Daniel Wilson finds no cats in the forest. Paws for More Outstanding Art at 32 Convention Cindy Weitzel makes a philanthropic gift to the FCF. Can I really buy a Cheetah on the Internet?! 35 Internet investigator Dolly Gluck wants answers. Small Cat Awareness in Massachusetts 45 Mona Headen attends show featuring Jim Sanderson, Debi Willoughby and Geoffroy’s cat Spirit. 25 Cover Photo: Gucci lays in wait for the Easter bunny. Photo by Rebecca Jensen, owner, A Wild Side Cattery. 15 16 45 Feline Conservation Federation Volume 55, Issue 3 • May/June 2011 TO SUBSCRIBE TO THE FCF JOURNAL AND JOINTHE FCF IN ITS CONSERVATION EFFORTS A membership to the FCF entitles you to six issues of the Journal, the back-issue DVD, an invitation to FCF hus- bandry and wildlife education courses and annual convention, and participation in our online discussion group. The FCF works to improve captive feline husbandry and ensure that habitat is available. -

Ali Kazemy T (+98) 863 624 1261 U (+98) 863 622 7814 B [email protected] Curriculum Vitae Í

Department of Electrical Engineering Tafresh University, Tafresh, Iran Ali Kazemy T (+98) 863 624 1261 u (+98) 863 622 7814 B [email protected] Curriculum Vitae Í http://faculty.tafreshu.ac.ir/kazemy/en Education 2007–2013 Doctor of Philosophy, Iran University of Science and Technology, Tehran, Iran. Electrical Engineering, Control 2004–2007 Master of Science, Iran University of Science and Technology, Tehran, Iran. Electrical Engineering, Control PhD Dissertation Title Robust Stability of Continuous-Time Lur’e Systems with Multiple Constant Time- delays Supervisor Professor Mohammad Farrokhi Masters Thesis Title Design and Simulation of Intelligent Image Control in Three-Degrees-of-Freedom Periscope with Implementation on an Experimental Setup Supervisor Professor Mohammad Farrokhi Description This thesis was specifically defined on a submarine periscope and successfully implemented on an experimental setup at Malek-Ashtar University of Technology. Employment History 2013–Present Assistant Professor, Department of Electrical Engineering, Tafresh University, Tafresh, Iran. 2014–Present Head of Short-term Training Courses, Tafresh University, Tafresh, Iran. 2017–Present Head of Incubator Center, Tafresh University, Tafresh, Iran. Miscellaneous 2006–2013 Chief Executive Officer (CEO), Bargh Afzar Farzam Company, Tehran, Iran. 2007–2008 Lecturer, Iran Petroleum Training Center, Tehran, Iran. Visiting & Research Positions 2019 Research Associate, Three months from 20th of May to 20th Aug, at the invitation of Professor James Lam (grant 69000 HK$), The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong. 1/5 Honors and Awards 2019 The Best Researcher, Markazi Province. 2019 The Best Researcher, Tafresh University. 2018 The Best Researcher (Triennial), Tafresh University. 2018 The Best Researcher (Yearly), Tafresh University. 2017 Selected Researcher, Tafresh University. -

Origin of the Egyptian Domestic Cat

UPTEC X 12 012 Examensarbete 30 hp Juni 2012 Origin of the Egyptian Domestic Cat Carolin Johansson Molecular Biotechnology Programme Uppsala University School of Engineering UPTEC X 12 012 Date of issue 2012-06 Author Carolin Johansson Title (English) Origin of the Egyptian Domestic Cat Title (Swedish) Abstract This study presents mitochondrial genome sequences from 22 Egyptian house cats with the aim of resolving the uncertain origin of the contemporary world-wide population of Domestic cats. Together with data from earlier studies it has been possible to confirm some of the previously suggested haplotype identifications and phylogeny of the Domestic cat lineage. Moreover, by applying a molecular clock, it is proposed that the Domestic cat lineage has experienced several expansions representing domestication and/or breeding in pre-historical and historical times, seemingly in concordance with theories of a domestication origin in the Neolithic Middle East and in Pharaonic Egypt. In addition, the present study also demonstrates the possibility of retrieving long polynucleotide sequences from hair shafts and a time-efficient way to amplify a complete feline mitochondrial genome. Keywords Feline domestication, cat in ancient Egypt, mitochondrial genome, Felis silvestris libyca Supervisors Anders Götherström Uppsala University Scientific reviewer Jan Storå Stockholm University Project name Sponsors Language Security English Classification ISSN 1401-2138 Supplementary bibliographical information Pages 123 Biology Education Centre Biomedical Center Husargatan 3 Uppsala Box 592 S-75124 Uppsala Tel +46 (0)18 4710000 Fax +46 (0)18 471 4687 Origin of the Egyptian Domestic Cat Carolin Johansson Populärvetenskaplig sammanfattning Det är inte sedan tidigare känt exakt hur, när och var tamkatten domesticerades. -

Sharma, V. & Sankhala, K. 1984. Vanishing Cats of Rajasthan. J in Jackson, P

Sharma, V. & Sankhala, K. 1984. Vanishing Cats of Rajasthan. J In Jackson, P. (Ed). Proceedings from the Cat Specialist Group meeting in Kanha National Park. p. 116-135. Keywords: 4Asia/4IN/Acinonyx jubatus/caracal/Caracal caracal/cats/cheetah/desert cat/ distribution/felidae/felids/Felis chaus/Felis silvestris ornata/fishing cat/habitat/jungle cat/ lesser cats/observation/Prionailurus viverrinus/Rajasthan/reintroduction/status 22 117 VANISHING CATS OF RAJASTHAN Vishnu Sharma Conservator of Forests Wildlife, Rajasthan Kailash Sankhala Ex-Chief Wildlife Warden, Rajasthan Summary The present study of the ecological status of the lesser cats of Rajasthan is a rapid survey. It gives broad indications of the position of fishing cats, caracals, desert cats and jungle cats. Less than ten fishing cats have been reported from Bharatpur. This is the only locality where fishing cats have been seen. Caracals are known to occur locally in Sariska in Alwar, Ranthambore in Sawaimadhopur, Pali and Doongargarh in Bikaner district. Their number is estimated to be less than fifty. Desert cats are thinly distributed over entire desert range receiving less than 60 cm rainfall. Their number may not be more than 500. Jungle cats are still found all over the State except in extremely arid zone receiving less than 20 cms of rainfall. An intelligent estimate places their population around 2000. The study reveals that the Indian hunting cheetah did not exist in Rajasthan even during the last century when ecological conditions were more favourable than they are even today in Africa. The cats are important in the ecological chain specially in controlling the population of rodent pests. -

Phylogeography of Indian Populations of Jungle Cat (Felis Chaus) and Leopard Cat (Prionailurus Bengalensis)

Cat Project of the Month – April 2008 The IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group's website (www.catsg.org) presents each month a different cat conservation project. Members of the Cat Specialist Group are encouraged to submit a short description of interesting projects Phylogeography of Indian populations of jungle cat (Felis chaus) and leopard cat (Prionailurus bengalensis) The family Felidae is well represented in India, with 15 species occurring here, making it the richest in cats worldwide. However, except for the large cats the rest figure very poorly in research and conservation policies in the country, probably because of their rarity and elusive nocturnal habits, coupled with cumbersome bureaucratic formalities in studying rare species. Fortunately, in the past few years non-invasive molecular techniques have been introduced in wildlife research in India, which has made small cat research easier. Shomita has studied diet and habitat use in fishing cat and jungle cat in Keoladeo Ghana National Park in Rajasthan as part of her Master’s dissertation and diet and habitat use in jungle cat, caracal and golden jackal in Sariska Tiger Reserve, Rajasthan for her PhD. Currently she is doing her post doctoral research at the National Centre for Biological Sciences, Bangalore, using non-invasive DNA analysis to address questions related to phylogeography of some small cats, human-large cat conflict and testing molecular techniques to survey small cats in India. Shomita has been a Cat SG member since 1995. [email protected] The study species: Leopard cat (top, Photo V. Lakshman), submitted: March 2007 Krishnapriya Tamma and Jungle cat (bottom, Photo J. -

Current Status of the Eurasian Lynx. Cat News. (2016)

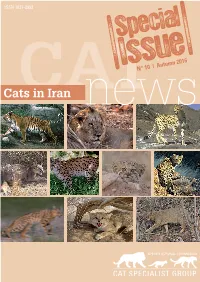

ISSN 1027-2992 I Special Issue I N° 10 | Autumn 2016 CatsCAT in Iran news 02 CATnews is the newsletter of the Cat Specialist Group, a component Editors: Christine & Urs Breitenmoser of the Species Survival Commission SSC of the International Union Co-chairs IUCN/SSC for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). It is published twice a year, and is Cat Specialist Group available to members and the Friends of the Cat Group. KORA, Thunstrasse 31, 3074 Muri, Switzerland For joining the Friends of the Cat Group please contact Tel ++41(31) 951 90 20 Christine Breitenmoser at [email protected] Fax ++41(31) 951 90 40 <[email protected]> Original contributions and short notes about wild cats are welcome Send <[email protected]> contributions and observations to [email protected]. Guidelines for authors are available at www.catsg.org/catnews Cover Photo: From top left to bottom right: Caspian tiger (K. Rudloff) This Special Issue of CATnews has been produced with support Asiatic lion (P. Meier) from the Wild Cat Club and Zoo Leipzig. Asiatic cheetah (ICS/DoE/CACP/ Panthera) Design: barbara surber, werk’sdesign gmbh caracal (M. Eslami Dehkordi) Layout: Christine Breitenmoser & Tabea Lanz Eurasian lynx (F. Heidari) Print: Stämpfli Publikationen AG, Bern, Switzerland Pallas’s cat (F. Esfandiari) Persian leopard (S. B. Mousavi) ISSN 1027-2992 © IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group Asiatic wildcat (S. B. Mousavi) sand cat (M. R. Besmeli) jungle cat (B. Farahanchi) The designation of the geographical entities in this publication, and the representation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Location Indicators by Indicator

ECCAIRS 4.2.6 Data Definition Standard Location Indicators by indicator The ECCAIRS 4 location indicators are based on ICAO's ADREP 2000 taxonomy. They have been organised at two hierarchical levels. 12 January 2006 Page 1 of 251 ECCAIRS 4 Location Indicators by Indicator Data Definition Standard OAAD OAAD : Amdar 1001 Afghanistan OAAK OAAK : Andkhoi 1002 Afghanistan OAAS OAAS : Asmar 1003 Afghanistan OABG OABG : Baghlan 1004 Afghanistan OABR OABR : Bamar 1005 Afghanistan OABN OABN : Bamyan 1006 Afghanistan OABK OABK : Bandkamalkhan 1007 Afghanistan OABD OABD : Behsood 1008 Afghanistan OABT OABT : Bost 1009 Afghanistan OACC OACC : Chakhcharan 1010 Afghanistan OACB OACB : Charburjak 1011 Afghanistan OADF OADF : Darra-I-Soof 1012 Afghanistan OADZ OADZ : Darwaz 1013 Afghanistan OADD OADD : Dawlatabad 1014 Afghanistan OAOO OAOO : Deshoo 1015 Afghanistan OADV OADV : Devar 1016 Afghanistan OARM OARM : Dilaram 1017 Afghanistan OAEM OAEM : Eshkashem 1018 Afghanistan OAFZ OAFZ : Faizabad 1019 Afghanistan OAFR OAFR : Farah 1020 Afghanistan OAGD OAGD : Gader 1021 Afghanistan OAGZ OAGZ : Gardez 1022 Afghanistan OAGS OAGS : Gasar 1023 Afghanistan OAGA OAGA : Ghaziabad 1024 Afghanistan OAGN OAGN : Ghazni 1025 Afghanistan OAGM OAGM : Ghelmeen 1026 Afghanistan OAGL OAGL : Gulistan 1027 Afghanistan OAHJ OAHJ : Hajigak 1028 Afghanistan OAHE OAHE : Hazrat eman 1029 Afghanistan OAHR OAHR : Herat 1030 Afghanistan OAEQ OAEQ : Islam qala 1031 Afghanistan OAJS OAJS : Jabul saraj 1032 Afghanistan OAJL OAJL : Jalalabad 1033 Afghanistan OAJW OAJW : Jawand 1034 -

Structural Development of a Major Late Cenozoic Basin and Transpressional Belt in Central Iran: the Central Basin in the Qom-Saveh Area

Structural development of a major late Cenozoic basin and transpressional belt in central Iran: The Central Basin in the Qom-Saveh area Chris K. Morley PTTEP (PTT Exploration and Production), Offi ce Building, 555 Vibhavadi Rangsit Road, Chatuchak, Bangkok 10900, Thailand Booncherd Kongwung PTTEP (PTT Exploration and Production), Tehran Branch Offi ce, Unit 5 & 6, 5th Floor Sayeh Tower, Vali-e-Asr Avenue, 19677 13671 Tehran, Iran Ali A. Julapour Mohsen Abdolghafourian Mahmoud Hajian National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) Exploration Directorate, 1st Dead-end, Seoul St., NE Sheikh Bahaei Sq., P.O. Box 19395-6669 Tehran, Iran Douglas Waples Consultant, PTTEP (PTT Exploration and Production), 555 Vibhavadi Rangsit Road, Chatuchak, Bangkok 10900, Thailand John Warren* Shell Chair in Carbonate Studies, Sultan Qaboos University, P.O. Box 17, Postal Code Al-Khodh-123, Muscat, Sultanate of Oman Heiko Otterdoom PTTEP (PTT Exploration and Production), Tehran Branch Offi ce, Unit 5 & 6, 5th Floor Sayeh Tower, Vali-e-Asr Avenue, 19677 13671 Tehran, Iran Kittipong Srisuriyon PTTEP (PTT Exploration and Production), Offi ce Building, 555 Vibhavadi Rangsit Road, Chatuchak, Bangkok 10900, Thailand Hassan Kazemi PTTEP (PTT Exploration and Production), Tehran Branch Offi ce, Unit 5 & 6, 5th Floor Sayeh Tower, Vali-e-Asr Avenue, 19677 13671 Tehran, Iran ABSTRACT as 4–5 km of Upper Red Formation section of Upper Red Formation were deposited being deposited in some parts of the basin in the main depocenters. Northwest-south- The Central Basin of the Iran Plateau during this stage. The upper part of the east– to north-northwest–south-southeast– is between the geologically better-known Upper Red Formation is associated with a striking dextral strike-slip to compressional regions of the Zagros and Alborz Moun- change to transpressional deformation, with faults dominate the area, with subordinate tains. -

Natural Epigenetic Variation Within and Among Six Subspecies of the House Sparrow, Passer Domesticus Sepand Riyahi1,*,‡, Roser Vilatersana2,*, Aaron W

© 2017. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Experimental Biology (2017) 220, 4016-4023 doi:10.1242/jeb.169268 RESEARCH ARTICLE Natural epigenetic variation within and among six subspecies of the house sparrow, Passer domesticus Sepand Riyahi1,*,‡, Roser Vilatersana2,*, Aaron W. Schrey3, Hassan Ghorbani Node4,5, Mansour Aliabadian4,5 and Juan Carlos Senar1 ABSTRACT methylation is one of several epigenetic processes (such as histone Epigenetic modifications can respond rapidly to environmental modification and chromatin structure) that can influence an ’ changes and can shape phenotypic variation in accordance with individual s phenotype. Many recent studies show the relevance environmental stimuli. One of the most studied epigenetic marks is of DNA methylation in shaping phenotypic variation within an ’ DNA methylation. In the present study, we used the methylation- individual s lifetime (e.g. Herrera et al., 2012), such as the effect of sensitive amplified polymorphism (MSAP) technique to investigate larval diet on the methylation patterns and phenotype of social the natural variation in DNA methylation within and among insects (Kucharski et al., 2008). subspecies of the house sparrow, Passer domesticus. We focused DNA methylation is a crucial process in natural selection on five subspecies from the Middle East because they show great and evolution because it allows organisms to adapt rapidly to variation in many ecological traits and because this region is the environmental fluctuations by modifying phenotypic traits, either probable origin for the house sparrow’s commensal relationship with via phenotypic plasticity or through developmental flexibility humans. We analysed house sparrows from Spain as an outgroup. (Schlichting and Wund, 2014).