Phylogeography of Indian Populations of Jungle Cat (Felis Chaus) and Leopard Cat (Prionailurus Bengalensis)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Small Carnivores in Tinjure-Milke-Jaljale, Eastern Nepal

SMALL CARNIVORES IN TINJURE-MILKE-JALJALE, EASTERN NEPAL The content of this booklet can be used freely with permission for any conservation and education purpose. However we would be extremely happy to get a hard copy or soft copy of the document you have used it for. For further information: Friends of Nature Kathmandu, Nepal P.O. Box: 23491 Email: [email protected], Website: www.fonnepal.org Facebook: www.facebook.com/fonnepal2005 First Published: April, 2018 Photographs: Friends of Nature (FON), Jeevan Rai, Zaharil Dzulkafly, www.pixabay/ werner22brigitte Design: Roshan Bhandari Financial support: Rufford Small Grants, UK Authors: Jeevan Rai, Kaushal Yadav, Yadav Ghimirey, Som GC, Raju Acharya, Kamal Thapa, Laxman Prasad Poudyal and Nitesh Singh ISBN: 978-9937-0-4059-4 Acknowledgements: We are grateful to Zaharil Dzulkafly for his photographs of Marbled Cat, and Andrew Hamilton and Wildscreen for helping us get them. We are grateful to www.pixabay/werner22brigitte for giving us Binturong’s photograph. We thank Bidhan Adhikary, Thomas Robertson, and Humayra Mahmud for reviewing and providing their valuable suggestions. Preferred Citation: Rai, J., Yadav, K., Ghimirey, Y., GC, S., Acharya, R., Thapa, K., Poudyal, L.P., and Singh, N. 2018. Small Carnivores in Tinjure-Milke-Jaljale, Eastern Nepal. Friends of Nature, Nepal and Rufford Small Grants, UK. Small Carnivores in Tinjure-Milke-Jaljale, Eastern Nepal Why Protect Small Carnivores! Small carnivores are an integral part of our ecosystem. Except for a few charismatic species such as Red Panda, a general lack of research and conservation has created an information gap about them. I am optimistic that this booklet will, in a small way, be the starting journey of filling these gaps in our knowledge bank of small carnivore in Nepal. -

Sharma, V. & Sankhala, K. 1984. Vanishing Cats of Rajasthan. J in Jackson, P

Sharma, V. & Sankhala, K. 1984. Vanishing Cats of Rajasthan. J In Jackson, P. (Ed). Proceedings from the Cat Specialist Group meeting in Kanha National Park. p. 116-135. Keywords: 4Asia/4IN/Acinonyx jubatus/caracal/Caracal caracal/cats/cheetah/desert cat/ distribution/felidae/felids/Felis chaus/Felis silvestris ornata/fishing cat/habitat/jungle cat/ lesser cats/observation/Prionailurus viverrinus/Rajasthan/reintroduction/status 22 117 VANISHING CATS OF RAJASTHAN Vishnu Sharma Conservator of Forests Wildlife, Rajasthan Kailash Sankhala Ex-Chief Wildlife Warden, Rajasthan Summary The present study of the ecological status of the lesser cats of Rajasthan is a rapid survey. It gives broad indications of the position of fishing cats, caracals, desert cats and jungle cats. Less than ten fishing cats have been reported from Bharatpur. This is the only locality where fishing cats have been seen. Caracals are known to occur locally in Sariska in Alwar, Ranthambore in Sawaimadhopur, Pali and Doongargarh in Bikaner district. Their number is estimated to be less than fifty. Desert cats are thinly distributed over entire desert range receiving less than 60 cm rainfall. Their number may not be more than 500. Jungle cats are still found all over the State except in extremely arid zone receiving less than 20 cms of rainfall. An intelligent estimate places their population around 2000. The study reveals that the Indian hunting cheetah did not exist in Rajasthan even during the last century when ecological conditions were more favourable than they are even today in Africa. The cats are important in the ecological chain specially in controlling the population of rodent pests. -

Hybrid Cats’ Position Statement, Hybrid Cats Dated January 2010

NEWS & VIEWS AAFP Position Statement This Position Statement by the AAFP supersedes the AAFP’s earlier ‘Hybrid cats’ Position Statement, Hybrid cats dated January 2010. The American Association of Feline Practitioners (AAFP) strongly opposes the breeding of non-domestic cats to domestic cats and discourages ownership of early generation hybrid cats, due to concerns for public safety and animal welfare issues. Unnatural breeding between intended mates can make The AAFP strongly opposes breeding difficult. the unnatural breeding of non- Domestic cats have 38 domestic to domestic cats. This chromosomes, and most commonly includes both natural breeding bred non-domestic cats have 36 and artificial insemination. chromosomes. This chromosomal The AAFP opposes the discrepancy leads to difficulties unlicensed ownership of non- in producing live births. Gestation domestic cats (see AAFP’s periods often differ, so those ‘Ownership of non-domestic felids’ kittens may be born premature statement at catvets.com). The and undersized, if they even AAFP recognizes that the offspring survive. A domestic cat foster of cats bred between domestic mother is sometimes required cats and non-domestic (wild) cats to rear hybrid kittens because are gaining in popularity due to wild females may reject premature their novelty and beauty. or undersized kittens. Early There are two commonly seen generation males are usually hybrid cats. The Bengal (Figure 1), sterile, as are some females. with its spotted coat, is perhaps The first generation (F1) female the most popular hybrid, having its offspring of a domestic cat bred to origins in the 1960s. The Bengal a wild cat must then be mated back is a cross between the domestic to a domestic male (producing F2), cat and the Asian Leopard Cat. -

Small Carnivores of Karnataka: Distribution and Sight Records1

Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, 104 (2), May-Aug 2007 155-162 SMALL CARNIVORES OF KARNATAKA SMALL CARNIVORES OF KARNATAKA: DISTRIBUTION AND SIGHT RECORDS1 H.N. KUMARA2,3 AND MEWA SINGH2,4 1Accepted November 2006 2 Biopsychology Laboratory, University of Mysore, Mysore 570 006, Karnataka, India. 3Email: [email protected] 4Email: [email protected] During a study from November 2001 to July 2004 on ecology and status of wild mammals in Karnataka, we sighted 143 animals belonging to 11 species of small carnivores of about 17 species that are expected to occur in the state of Karnataka. The sighted species included Leopard Cat, Rustyspotted Cat, Jungle Cat, Small Indian Civet, Asian Palm Civet, Brown Palm Civet, Common Mongoose, Ruddy Mongoose, Stripe-necked Mongoose and unidentified species of Otters. Malabar Civet, Fishing Cat, Brown Mongoose, Nilgiri Marten, and Ratel were not sighted during this study. The Western Ghats alone account for thirteen species of small carnivores of which six are endemic. The sighting of Rustyspotted Cat is the first report from Karnataka. Habitat loss and hunting are the major threats for the small carnivore survival in nature. The Small Indian Civet is exploited for commercial purpose. Hunting technique varies from guns to specially devised traps, and hunting of all the small carnivore species is common in the State. Key words: Felidae, Viverridae, Herpestidae, Mustelidae, Karnataka, threats INTRODUCTION (Mukherjee 1989; Mudappa 2001; Rajamani et al. 2003; Mukherjee et al. 2004). Other than these studies, most of the Mammals of the families Felidae, Viverridae, information on these animals comes from anecdotes or sight Herpestidae, Mustelidae and Procyonidae are generally records, which no doubt, have significantly contributed in called small carnivores. -

Flat Headed Cat Andean Mountain Cat Discover the World's 33 Small

Meet the Small Cats Discover the world’s 33 small cat species, found on 5 of the globe’s 7 continents. AMERICAS Weight Diet AFRICA Weight Diet 4kg; 8 lbs Andean Mountain Cat African Golden Cat 6-16 kg; 13-35 lbs Leopardus jacobita (single male) Caracal aurata Bobcat 4-18 kg; 9-39 lbs African Wildcat 2-7 kg; 4-15 lbs Lynx rufus Felis lybica Canadian Lynx 5-17 kg; 11-37 lbs Black Footed Cat 1-2 kg; 2-4 lbs Lynx canadensis Felis nigripes Georoys' Cat 3-7 kg; 7-15 lbs Caracal 7-26 kg; 16-57 lbs Leopardus georoyi Caracal caracal Güiña 2-3 kg; 4-6 lbs Sand Cat 2-3 kg; 4-6 lbs Leopardus guigna Felis margarita Jaguarundi 4-7 kg; 9-15 lbs Serval 6-18 kg; 13-39 lbs Herpailurus yagouaroundi Leptailurus serval Margay 3-4 kg; 7-9 lbs Leopardus wiedii EUROPE Weight Diet Ocelot 7-18 kg; 16-39 lbs Leopardus pardalis Eurasian Lynx 13-29 kg; 29-64 lbs Lynx lynx Oncilla 2-3 kg; 4-6 lbs Leopardus tigrinus European Wildcat 2-7 kg; 4-15 lbs Felis silvestris Pampas Cat 2-3 kg; 4-6 lbs Leopardus colocola Iberian Lynx 9-15 kg; 20-33 lbs Lynx pardinus Southern Tigrina 1-3 kg; 2-6 lbs Leopardus guttulus ASIA Weight Diet Weight Diet Asian Golden Cat 9-15 kg; 20-33 lbs Leopard Cat 1-7 kg; 2-15 lbs Catopuma temminckii Prionailurus bengalensis 2 kg; 4 lbs Bornean Bay Cat Marbled Cat 3-5 kg; 7-11 lbs Pardofelis badia (emaciated female) Pardofelis marmorata Chinese Mountain Cat 7-9 kg; 16-19 lbs Pallas's Cat 3-5 kg; 7-11 lbs Felis bieti Otocolobus manul Fishing Cat 6-16 kg; 14-35 lbs Rusty-Spotted Cat 1-2 kg; 2-4 lbs Prionailurus viverrinus Prionailurus rubiginosus Flat -

2019 Cat Specialist Group Report

IUCN SSC Cat Specialist Group 2019 Report Christine Breitenmoser Urs Breitenmoser Co-Chairs Mission statement Research activities: develop camera trapping Christine Breitenmoser (1) Cat Manifesto database which feeds into the Global Mammal Urs Breitenmoser (2) (www.catsg.org/index.php?id=44). Assessment and the IUCN SIS database. Technical advice: (1) develop Cat Monitoring Guidelines; (2) conservation of the Wild Cat Red List Authority Coordinator Projected impact for the 2017-2020 (Felis silvestris) in Scotland: review of the Tabea Lanz (1) quadrennium conservation status and assessment of conser- By 2020, we will have implemented the Assess- Location/Affiliation vation activities. Plan-Act (APA) approach for additional cat (1) Plan KORA, Muri b. Bern, Switzerland species. We envision improving the status (2) Planning: (1) revise the National Action Plan for FIWI/Universtiät Bern and KORA, Muri b. assessments and launching new conservation Asiatic Cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus) in Bern, Switzerland planning processes. These conservation initia- Iran; (2) participate in Javan Leopard (Panthera tives will be combined with communicational pardus melas) workshop; (3) facilitate lynx Number of members and educational programmes for people and workshop; (4) develop conservation strategy for 193 institutions living with these species. the Pallas’s Cat (Otocolobus manul); (5) plan- ning for the Leopard in Africa and Southeast Social networks Targets for the 2017-2020 quadrennium Asia; (6) updating and coordination for the Lion Facebook: IUCN SSC Cat Specialist Group Assess (Panthera leo) Conservation Strategy; (7) facil- Website: www.catsg.org Capacity building: attend and facilitate a work- itate a workshop to develop a conservation shop to develop recommendations for the strategy for the Jaguar (Panthera onca) in a conservation of the Persian Leopard (Panthera number of neglected countries in collaboration pardus tulliana) in July 2020. -

Wilcox D. H. A., Tran Quang Phuong, Hoang Minh Duc & Nguyen The

Wilcox D. H. A., Tran Quang Phuong, Hoang Minh Duc & Nguyen The Truong An. 2014. The decline of non-Panthera cats species in Vietnam. Cat News Special Issue 8, 53-61. Supporting Online Material SOM T1-T3. SOM T1. Conservation categorisation of the six non-Panthera cat species in Vietnam. Common name Species name IUCN Red List1 Vietnam Red Book2 marbled cat Pardofelis marmorata Vulnerable Vulnerable Asiatic golden cat Pardofelis temminckii Near Threatened Endangered clouded leopard Neofelis nebulosa Vulnerable Endangered jungle cat Felis chaus Least Concern Data Deficient leopard cat Prionailurus bengalensis Least Concern Not Listed fishing cat Prionailurus viverrinus Endangered Endangered 1 Conservation status according to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Current listings are based on the 2008 Global Mammal Assessment (GMA) 2 Conservation status according to the 2007 Red Data Book of Vietnam Part 1: animals, developed and written Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology [VAST] SOM T2. Traceable verifiable leopard cat Prionailurus bengalensis records from Vietnam. Site Province(s) Main habitat(s) at site1 Record type2 Reference Ba Na NR Da Nang Lowland to lower montane O Frontier Vietnam evergreen (1996a) Bach Ma NP Thua Thien Hue Lowland to submontane CT Dickinson & Van evergreen Ngoc Thinh (2006) Ben En NP Thanh Hoa Lowland semi-evergreen and O, R Frontier Vietnam evergreen (2000a) Cat Ba NP Hai Phong Lowland evergreen on O Frontier Vietnam limestone (2002) Cat Ba NP Hai Phong Lowland evergreen on CT, O - spotlit Abramov & limestone Kruskop (2012) Cat Tien NP Dong Nai Lowland semi-evergreen and CT, O - spotlit Nguyen The evergreen Truong An in litt. -

Study on the Behavior of Lesser Carnivores Mammals in Darjeeling Zoo

REPORT WRITING - STUDY ON THE BEHAVIOR OF LESSER CARNIVORES MAMMALS IN DARJEELING ZOO Submitted to: The Director Padmaja Naidu Himalayan Zoological Park Darjeeling Submitted by: Ms. Deena Gurung Duration: 1st May- 31st May 2014 CONTENT ACKNOWLEDGEMENT 1 ABSTRACT 2 INTRODUCTION 2 ILLUSTRATIONS 3 THREATS (ILLUSTRATIONS) 4 IMPORTANCE OF BEHAVIOR 5 STUDY METHODOLOGY 6 RESULT 6-7 CONCLUSION 8 DISCUSSION 9 REFERENCE 9-10 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The study entitled ‘Study on the behavior of lesser carnivores mammals at Darjeeling Zoo’ was conducted by me, for a period of one month (May 2014). My sincere thanks to Mr. A. K. Jha, IFS, Director of PNHZP for giving me this wonderful opportunity to work and learn in this institution. I also thank him for his inspirations towards the students and scholars. I would like to thank all the staffs of PNHZP; Mr. Shiromani Syangden, Estate Officer, Mr. Purna Ghising, Supervisor, Mr. Deepak Roka, Asst. Supervisor for their encouragements and helpfulness. My deepest gratitude goes to Ms. Upashna Rai, Scientific Officer, for her guidance and patience during the study. I would also like to thank Mr. Bhupen Roka, Education Officer and the research scholars for their invaluable support and cooperation. I am grateful to the veterinary doctors, Mr. Vikash Chettri, Mr. Pankaj Kumar and Mr. Pradip Singh for sharing their invaluable informations and knowledge during the period. My heartfelt thanks goes to the all the zookeepers especially Mr. Sanil Rai, Mr. Nippon and Mr. Nima Tamang for being so considerate and helpful. Theyears of experience they shared with the animals here, helped me to better understand the animals under study. -

Fishing Cat Prionailurus Viverrinus Bennett, 1833

Journal of Threatened Taxa | www.threatenedtaxa.org | 26 October 2018 | 10(11): xxxxx–xxxxx Fishing Cat Prionailurus viverrinus Bennett, 1833 (Carnivora: Felidae) distribution and habitat characteristics Communication in Chitwan National Park, Nepal ISSN 0974-7907 (Online) ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) Rama Mishra 1 , Khadga Basnet 2 , Rajan Amin 3 & Babu Ram Lamichhane 4 OPEN ACCESS 1,2 Central Department of Zoology, Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur, Kathmandu, Nepal 3 Conservation Programmes, Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4RY, UK 4 National Trust for Nature Conservation - Biodiversity Conservation Center, Ratnanagar-6, Sauraha, Chitwan, Nepal 1 [email protected] (corresponding author), 2 [email protected], 3 [email protected], 4 [email protected] Abstract: The Fishing Cat is a highly specialized and threatened felid, and its status is poorly known in the Terai region of Nepal. Systematic camera-trap surveys, comprising 868 camera-trap days in four survey blocks of 40km2 in Rapti, Reu and Narayani river floodplains of Chitwan National Park, were used to determine the distribution and habitat characteristics of this species. A total of 19 photographs of five individual cats were recorded at three locations in six independent events. Eleven camera-trap records obtained during surveys in 2010, 2012 and 2013 were used to map the species distribution inside Chitwan National Park and its buffer zone. Habitat characteristics were described at six locations where cats were photographed. The majority of records were obtained in tall grassland surrounding oxbow lakes and riverbanks. Wetland shrinkage, prey (fish) depletion in natural wetlands and persecution threaten species persistence. Wetland restoration, reducing human pressure and increasing fish densities in the wetlands, provision of compensation for loss from Fishing Cats and awareness programs should be conducted to ensure their survival. -

Some Wild Cats Have Stripes. Like the Tiger!

Wild Cat! Wild Cat! Author: Sejal Mehta Illustrator: Rohan Chakravarty Some wild cats have stripes. Like the tiger! 2 Some wild cats have manes. Like the lion! 3 Some wild cats have spots. Like the leopard and the leopard cat! 4 Some wild cats are the best climbers. Like the clouded leopard and the marbled cat! 5 Some wild cats live high up in the mountains. Like the snow leopard and the Pallas's cat! 6 Some wild cats live in the desert. Like the desert cat! 7 Some wild cats have hairy ears. Like the caracal and the lynx! 8 Some wild cats love to fish. Like the fishing cat! 9 Some wild cats are the smallest wild cats in the world. Like the rusty-spotted cat! 10 Some wild cats look like house cats. Like the jungle cat and the golden cat! 11 But they are all wild cats! 12 This book was made possible by Pratham Books' StoryWeaver platform. Content under Creative Commons licenses can be downloaded, translated and can even be used to create new stories ‐ provided you give appropriate credit, and indicate if changes were made. To know more about this, and the full terms of use and attribution, please visit the following link. Story Attribution: This story: Wild Cat! Wild Cat! is written by Sejal Mehta . © Pratham Books , 2017. Some rights reserved. Released under CC BY 4.0 license. Other Credits: 'Wild Cat! Wild Cat!' has been published on StoryWeaver by Pratham Books. www.prathambooks.org Images Attributions: Cover page: House cat looking at wild cats, by Rohan Chakravarty © Pratham Books, 2017. -

Baseline Information and Status Assessment of the Pallas's Cat in Iran

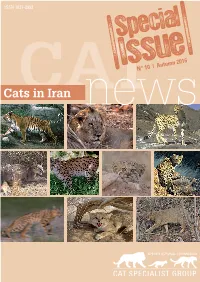

ISSN 1027-2992 I Special Issue I N° 10 | Autumn 2016 CatsCAT in Iran news 02 CATnews is the newsletter of the Cat Specialist Group, a component Editors: Christine & Urs Breitenmoser of the Species Survival Commission SSC of the International Union Co-chairs IUCN/SSC for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). It is published twice a year, and is Cat Specialist Group available to members and the Friends of the Cat Group. KORA, Thunstrasse 31, 3074 Muri, Switzerland For joining the Friends of the Cat Group please contact Tel ++41(31) 951 90 20 Christine Breitenmoser at [email protected] Fax ++41(31) 951 90 40 <[email protected]> Original contributions and short notes about wild cats are welcome Send <[email protected]> contributions and observations to [email protected]. Guidelines for authors are available at www.catsg.org/catnews Cover Photo: From top left to bottom right: Caspian tiger (K. Rudloff) This Special Issue of CATnews has been produced with support Asiatic lion (P. Meier) from the Wild Cat Club and Zoo Leipzig. Asiatic cheetah (ICS/DoE/CACP/ Panthera) Design: barbara surber, werk’sdesign gmbh caracal (M. Eslami Dehkordi) Layout: Christine Breitenmoser & Tabea Lanz Eurasian lynx (F. Heidari) Print: Stämpfli Publikationen AG, Bern, Switzerland Pallas’s cat (F. Esfandiari) Persian leopard (S. B. Mousavi) ISSN 1027-2992 © IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group Asiatic wildcat (S. B. Mousavi) sand cat (M. R. Besmeli) jungle cat (B. Farahanchi) The designation of the geographical entities in this publication, and the representation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

The Wild Cat Trade in Myanmar (PDF, 1.1

THE WILD CAT TRADE IN MYANMAR CHRIS R. SHEPHERD VINCENT NIJMAN A TRAFFIC SOUTHEAST ASIA REPORT Published by TRAFFIC Southeast Asia, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia © 2008 TRAFFIC Southeast Asia All rights reserved. All material appearing in this publication is copyrighted and may be reproduced with permission. Any reproduction in full or in part of this publication must credit TRAFFIC Southeast Asia as the copyright owner. The views of the authors expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the TRAFFIC Network, WWF or IUCN. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The TRAFFIC symbol copyright and Registered Trademark ownership is held by WWF. TRAFFIC is a joint programme of WWF and IUCN. Layout by Noorainie Awang Anak, TRAFFIC Southeast Asia Suggested citation: Chris R. Shepherd and Vincent Nijman (2008): The wild cat trade in Myanmar. TRAFFIC Southeast Asia, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia ISBN 9833393152 Cover: Spotted Golden Cat Catopuma temminckii skin Photograph credit: Chris R. Shepherd/TRAFFIC Southeast Asia THE WILD CAT TRADE IN MYANMAR Chris R. Shepherd and Vincent Nijman Chris R. Shepherd/TRAFFIC Southeast Asia Chris R. Shepherd/TRAFFIC Southeast Leopard Cat Prionailurus bengalensis and juvenile Leopard Panthera pardus skins displayed at a stall in Tachilek CONTENT Acknowledgements iii Executive Summary iv Introduction 1 Methods 3 Results 5 The Markets 7 Tachilek 7 Golden Rock 8 Mong La 8 Three Pagodas Pass 9 China and Thailand border towns 9 Myanmar border towns 10 Conclusion 11 Recommendations 12 References 13 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank the WWF AREAS Programme for generously funding our work in Myanmar.