San Bernardino Associated Governments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IEDC Data Standards for San Bernardino County

TABLE 1 SAN BERNARDINO COUNTY DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS Population Five Year Projection 2000 2008 2009 2013 Population by Age Group Under - 17 551,976 605,352 609,972 650,474 18 - 34 418,811 555,767 552,116 606,492 35 - 54 476,248 559,899 552,040 618,066 55 - 74 192,482 266,520 275,549 349,543 75 - Older 65,300 76,443 78,243 90,279 % Distribution by Age Group Under - 17 32.29% 29.30% 29.50% 28.10% 18 - 34 24.50% 26.90% 26.70% 26.20% 35 - 54 27.86% 27.10% 29.69% 26.70% 55 - 74 11.26% 12.90% 13.33% 15.10% 75 - Older 3.82% 3.70% 3.76% 3.90% Median Age 30.4 30.8 30.98 32.2 Percent Change 1990-2000 20.50% Percent Change 2000-2008 20.90% Percent Change 1990-2008 45.70% Percent Change 2008-2013 12.00% Households Number 464,737 620,777 617,191 677,480 Median Household Income 42,881 53,036 56,079 60,218 Household Income Distribution Under - $35,000 142,096 202,994 191,038 212,554 $35,001 - $50,000 68,920 98,457 88,026 105,302 $50,001 - $75,000 113,856 162,651 121,455 176,125 $75,001 - Above 140,792 201,131 216,672 232,172 Workforce Education Attainment (25 - 64 Years of Age) Percentage % Under - 12 Years 10.27 12 - 15 Years 15.23 12 Years Only 25.11 Some College 25.95 Associate Degrees 7.6 Subtotal 84.16 College Graduates 15.82 16 Years - More 5.45 16 Years Only 10.37 Total 15.82 TABLE 2 SAN BERNARDINO COUNTY LABOR FORCE CHARACTERISTICS Civilian Labor Force 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 Unemployment Rate (for month & year use most 5.20% 4.80% 6.00% 8.00% 13.90% recent information available and seasonally adjusted annual average) Non-Agricultural Employment -

Final Gold Line Report

STRATEGIC PLANNING STUDY REPORT FOR METRO GOLD LINE FOOTHILL EXTENSION TO LA/ONTARIO INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT PREPARED FOR Metro Gold Line Foothill Extension Construction Authority Funded By San Bernardino Associated Governments and The Southern California Association of Governments December 2008 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: Metro Gold Line Foothill Extension Construction Authority Southern California Association of Governments San Bernardino Associated Governments San Bernardino County Board of Supervisors Los Angeles World Airports PREPARED BY: KOA Corporation In Association with: STV Incorporated J.L. Patterson & Associates, INC. Consensus Planning Group, Inc. CITYWORKS DESIGN Metro Gold Line Foothill Extension to LA/Ontario International Airport Strategic Planning Study Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................... E-1 BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................................................................. E-1 PLANNING TEAM APPROACH AND PUBLIC OUTREACH .......................................................................................................... E-1 THE ALIGNMENTS ........................................................................................................................................................................ E-2 ADDITIONAL STUDY CONSIDERATIONS ................................................................................................................................... -

Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) What Is the MUTCD?

National Committee on Uniform Traffic Control Devices Bus/BRT Applications Introduction • I am Steve Andrle from TRB standing in for Randy McCourt, DKS Associates and 2019 ITE International Vice President • I co-manage with Claire Randall15 TRB public transit standing committees. • I want to bring you up to date on planned bus- oriented improvements to the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) What is the MUTCD? • Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) – Standards for roadway signs, signals, and markings • Authorized in 23 CFR, Part 655: It is an FHWA document. • National Committee on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (NCUTCD) develops content • Sponsored by 19 organizations including ITE, AASHTO, APTA and ATSSA (American Traffic Safety Services Association) Background • Bus rapid transit, busways, and other bus applications have expanded greatly since the last edition of the MUTCD in 2009 • The bus-related sections need to be updated • Much of the available research speaks to proposed systems, not actual experience • The NCUTCD felt it was a good time to survey actual systems to see what has worked, what didn’t work, and to identify gaps. National Survey • The NCUTCD established a task force with APTA and FTA • Working together they issued a survey in April of 2018. I am sure some of you received it. • The results will be released to the NCUTCD on June 20 – effectively now • I cannot give you any details until the NCUTCD releases the findings Survey Questions • Have you participated in design and/or operations of -

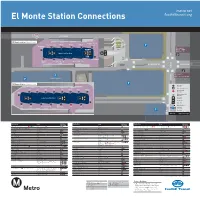

El Monte Station Connections Foothilltransit.Org

metro.net El Monte Station Connections foothilltransit.org BUSWAY 10 Greyhound Foothill Transit El Monte Station Upper Level FT Silver Streak Discharge Only FT486 FT488 FT492 Eastbound Metro ExpressLanes Walk-in Center Discharge 24 25 26 27 28 Only Bus stop for: 23 EMT Red, EMT Green EMS Civic Ctr Main Entrance Upper Level Bus Bays for All Service B 29 22 21 20 19 18 Greyhound FT481 FT Silver Streak Metro Silver Line Metro Bike Hub FT494 Westbound RAMONA BL RAMONA BL A Bus stop for: EMS Flair Park (am/pm) Metro Parking Structure Division 9 Building SANTA ANITA AV El Monte Station Lower Level 1 Bus Bay A Bus Stop (on street) 267 268 487 190 194 FT178 FT269 FT282 2 Metro Rapid 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Bus Bay 577X Metro Silver Line 8 18 Bus Bay Lower Level Bus Bays Elevator 76 Escalator 17 Bike Rail 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 EMS Bike Parking 270 176 Discharge Only Commuter 770 70 Connection Parking Building 13-0879 ©2012 LACMTA DEC 2012 Subject to Change Destinations Lines Bus Bay or Destinations Lines Bus Bay or Destinations Lines Bus Bay or Street Stop Street Stop Street Stop 7th St/Metro Center Rail Station Metro Silver Line 18 19 Hacienda Heights FT282 16 Pershing Square Metro Rail Station Metro Silver Line , 70, 76, 770, 1 2 17 18 37th St/USC Transitway Station Metro Silver Line 18 19 FT Silver Streak 19 20 21 Harbor Fwy Metro Rail Station Metro Silver Line 18 19 Pomona TransCenter ÅÍ FT Silver Streak 28 Alhambra 76, 176 6 17 Highland Park 176 6 Altadena 267, 268 9 10 Puente Hills Mall FT178, FT282 14 16 Industry Å 194, FT282 13 16 Arcadia 268, -

South Coast AQMD Continues Smoke Advisory Due to Bobcat Fire and El Dorado Fire

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: September 16, 2020 MEDIA CONTACT: Bradley Whitaker, (909) 396-3456, Cell: (909) 323-9516 Nahal Mogharabi, (909) 396-3773, Cell: (909) 837-2431 [email protected] South Coast AQMD Continues Smoke Advisory Due to Bobcat Fire and El Dorado Fire Valid: Wednesday, September 16, through Thursday, September 17, 2020 This advisory is in effect through Thursday evening. South Coast AQMD will issue an update if additional information becomes available. Two major local wildfires as well as wildfires in Northern and Central California are affecting air quality in the region. A wildfire named the Bobcat Fire is burning north of Azusa and Monrovia in the Angeles National Forest. As of 6:50 a.m. on Wednesday, the burn area was approximately 44,393 acres with 3% containment. Current information on the Bobcat Fire can be found on the Incident Information System (InciWeb) at https://inciweb.nwcg.gov/incident/7152. A wildfire named the El Dorado Fire is burning in the San Bernardino Mountains near Yucaipa in San Bernardino County. As of 6:51 a.m. on Wednesday, the burn area was reported at 18,092 acres with 60% containment. Current information on the El Dorado Fire can be found on the Incident Information System at: https://inciweb.nwcg.gov/incident/7148/. In addition, smoke from fires in Central California, Northern California, Oregon, and Washington are also being transported south and may impact air quality in the South Coast Air Basin and Coachella Valley. Past and Current Smoke and Ash Impacts Both the Bobcat Fire and the El Dorado fires are producing substantial amounts of smoke on Wednesday morning. -

SATS Final Transit Element Report

PPPINAL CCCOUNTY small area transportation study FINAL Transit Element Report PPPREPARED FFFOROROR ::: PPPINAL CCCOUNTY DDDEVELOPMENT SSSERVICES DDDEPARTMENT OF PPPUBLIC WWWORKS PPPREPARED BBBYYY::: KKKIRKHAM MMMICHAEL CCCONSULTING EEENGINEERS IIININ AAASSOCIATIONASSOCIATION WITH LLLIMA &&& AAASSOCIATES August 2006 KM Project # 0504900 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXISTING TRANSIT CONDITIONS ..............................................................1 1.1 Existing Transit Characteristics ................................................................................... 1 1.1.1 Demographics ....................................................................................................................1 1.1.2 Current Mode to Work .......................................................................................................2 1.2 Existing Transit Services ............................................................................................. 2 1.2.1 Coolidge Cotton Express....................................................................................................2 1.2.2 Inter-city Bus Service..........................................................................................................3 1.2.3 Special Needs Transit Services ...........................................................................................4 1.2.4 Amtrak Passenger Rail Service ...........................................................................................4 1.2.5 Regional Airport Shuttle .....................................................................................................7 -

REDLANDS PASSENGER RAIL PROJECT (ARROW) Plan. Build

REDLANDS PASSENGER RAIL PROJECT (ARROW) Arrow connects to • Mountain Transit San Bernardino – 210 • Omnitrans to CSUSB to Downtown Station • Pass Transit • Victor Valley Transit Overview San Bernardino Santa Fe Depot The Redlands Passenger Rail Project is an innovative nine-mile regional Tippecanoe Metrolink connects to Station N • Los Angeles INTERSTATE rail project that provides additional transportation choices through the CALIFORNIA • Orange County 10 University introduction of a new rail service, known as the Arrow, which integrates • San Diego Station • Riverside INTERSTATE • Ventura CALIFORNIA conveniently with other modes of transportation such as auto, bus and 215 Esri to Loma Linda University Station bicycle. Medical Center Redlands – N Downtown Station The Arrow will connect San Bernardino and Redlands and will offer residents, businesses and visitors a new commuting option to travel to a variety of leisure, education, healthcare and other destinations. Diesel Multiple Units (DMUs) have been identified as the preferred vehicle to provide primary service for the project. The DMUs are powered by an on-board low-emission, Clean Diesel engine which are smaller, quieter, more Funding efficient, and cheaper to operate than standard locomotive haul coaches, similar to Metrolink. DMUs work interoperably on the same track as Metrolink FEDERAL $86.0 Million and freight train services which allows for all three train services to use the STATE $164.6 Million same track in the existing corridor. LOCAL $109.1 Million (Includes Measure I) In addition to local commuter service, a Metrolink locomotive hauled coach train will also provide round trip express service from Redlands-to-Los TOTAL $359.7 Million Angeles each morning with return trip from Los Angeles-to-Redlands each evening. -

Victor Valley Town Center Nec Bear Valley Rd & Hesperia Rd | Victorville, Ca

OFFERING MEMORANDUM VICTOR VALLEY TOWN CENTER NEC BEAR VALLEY RD & HESPERIA RD | VICTORVILLE, CA CAPITAL MARKETS | INVESTMENT PROPERTIES Shane Hariz Matthew C. Sullivan Alan Krueger Senior Investment Advisor, Partner Managing Director, Principal Senior Vice President 213-623-0800 ext. 2 213-623-0800 ext. 1 909-418-2062 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] BRE License # 02025736 BRE License # 00848427 BRE License # 00880814 CONFIDENTIALITY AGREEMENT The information contained in the following Marketing Proposal is proprietary and strictly confidential. It is intended to be reviewed only by the party receiving it from Lee & Associates - Investment Services Group and should not TABLE OF CONTENTS be made available to any other person or entity without the written consent of Lee & Associates Investment Services Group. This Marketing Proposal has been prepared to 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................... 3 provide summary, unverified information to the aforementioned owner of the property 2. PROPERTY DESCRIPTION .................. 5 receiving it. The information contained herein is not a substitute for a thorough due diligence 3. TENANT PROFILES ......................... 11 investigation. Lee & Associates Investment Services Group has not made any investigation, 4. FINANCIAL ANALYSIS ................... 1 5 and makes no warranty or representation, with respect to the income or expenses for the 5. MARKET OVERVIEW ....................... 20 subject property, the future projected financial performance of the property, the size and square footage of the property and improvements, the presence or absence of contaminating substances, PCB’s or asbestos, the compliance with State and Federal regulations, the physical condition of the improvements thereon, or the financial condition or business prospects of any tenant, or any tenant s plans or intentions to continue its occupancy of the subject property. -

Inland Empire Family Resource Center Coalition (Iefrcc)

2012 INLAND EMPIRE Update June 1 Inland Empire Directory of FAMILY RESOURCE CENTERS J ~A{ /ilL I mily Re ourc C nt r FAMILY Hearts&Lives RESOURCE CENTER Resource Directory is provided by the Inland Empire Family Resource Center Coalition (ieFRCC) 2012 The Directory of Family Resource Centers in the Inland Empire is a compilation of known Family Resource Centers operating in the Inland Empire. The purpose is to improve the delivery of client services in San Bernardino County and Riverside County. The following Family Resource Centers are provided as a resource and not a referral. It is a collaborative process and every effort is made to represent each Family Resource Center with their most current services and contact information. However funding, staff transitions, and changes in client services in the Inland Empire can make it challenging for the Directory to be current at time of printing and online updates. Family Resource Centers that do not contain complete contact information & description of services have not been confirmed prior to printing of this Directory. Updates to the Directory are quarterly during the following months: January, April, July, and October. To download the most recent copy visit www.ieFRC.org Your help in keeping the Directory most current is appreciated and can help service providers that are using the Directory link clients more effectively and efficiently. To edit or add information please email [email protected] Family Resource Centers that are presented in the directory in bold and underlined are current members of the Inland Empire Family Resource Center Coalition (ieFRCC); creator and administer of the Directory. -

Pacific Electric Trail

Pacific Electric Trail Fontana, Seven Year Budget California 2009/2010 A City of Action 2015/2016 ABOUT THE COVER For the City of Fontana’s Fiscal Year 2009-2010 Adopted Capital Improvement Program, a cover highlighting “the Pacific Electric Inland Empire Trail” is featured. The Pacific Electric Trail (PE Trail) is proposed as a 20 mile, regional, multi-purpose trail extending from Claremont, through Upland, Rancho Cucamonga, Fontana, and Rialto. The trail was adopted by all the cities it traverses to promote non-motorized travel and other clean air programs. The Master Plan has been completed, and the individual cities have been implementing their respective portions of the PE Trail. Approximately 6.5 miles of the PE Trail traverses through Fontana. As shown on the map below, the City has divided the PE Trail Segment 5B 6.5 miles of PE Trail into six major segments. The existing abandoned railroad right-of-way, on which the PE Trail is located, is 80 feet wide and is consistent throughout each segment. The southerly 35 feet is dedicated to the multi-purpose trail which will consist of a 15 foot wide concrete paved walking/jogging/bike path and landscaping. The northerly 45 feet of that right-of-way is reserved for future rail considerations however, the area may also be landscaped. Four years ago Segment 1 of the PE Trail, a .75 mile segment through the downtown and Civic Center area, was completed. Segment 5A, a .43 mile segment in the Village of Heritage, was completed shortly thereafter. In January 2009 Segment 2, approximately .94 of a mile running from Juniper Ave to Tokay Ave, was completed. -

Transportation & Mobility Element (Policy Maps)

Policy Map TM-1 Roadway Network County Boundary Roadway Designation Community Planning Area Freeway Incorporated City/Town Major Divided Highway Major Roadway w/o Designa tion Major Arterial Highway Major Highway Secondary Highway Controlled/Limited Access Collector Mountain Major Highway Mountain Secondary Highway State Highway (Special Standards or Conditions) Æÿ15 ÿÆ58 ÿÆ40 ÿÆ15 Æÿ395 Æÿ40 ÿÆ247 ÿÆ18 ÿÆ15 ÿÆ18 ÿÆ138 Æÿ247 ÿÆ173 ÿÆ15 ÿÆ138 Æÿ18 ÿÆ215 Æÿ38 Æÿ30 ÿÆ330 Æÿ210 ÿÆ210 Æ Æ Æÿ62 ÿ62 Æÿ15 ÿ66 ÿÆ215 Æ Æÿ10 ÿ83 Æ ÿÆ60 ÿ10 ÿÆ71 Miles 0 4 8 12 16 Date: 7/6/2020 Created by PlaceWorks, Fehr & Peers | Source: County of San Bernardino 2018 G r an d A v e Arrow Hwy Arrow Walnut Walnut vAe Æ ÿ 71 71 Ed sion A e v EdA sion e B u t t e Central Ave r f i e l d R a n c h San An R d d Mt Bal Mountain Ave Heigh 16Th 16Th St Riverside Dr E u d d i c l v e e 8Th 8Th St A ton Æ ÿ 83 83 t dy s Hol Hol io Fourth Fourth St t Blvd MtBa l dy Campus Ave R d 0 ÿÆ 60 Gro ev Ave Mission Blvd Blvd Mission t an Sil 1 nerCa Vineyard Ave 19Th St W 2 il Archibald Ave son Ave Æ ÿ 210 Jurupa Jurupa St 3 Haven Ave Base Lne Rd Valley Valley 4 Milliken A ve i Airport Airport Dr 5 M Æ ÿ Banyan Banyan St iles 15 15 Day Creek Blvd Etiwanda Ave Ly Ly Date:7/6/2020 Mulb rery Ave t l Arrow Arrow Rte e Creek Ch rery Ave Basel Basel uJ S rupa Ave ine Ave H u i m g m Beech Ave h L y t l l i e t C a r n A e Created by PlaceWorks, Fehr & | Peers Source: County of San Bernardino 2018 e d v k R e d Æ ÿ A 10 Va l Va Æ ÿ v Citrus Ave 15 e e l ey ey Blvd Æ ÿ 210 San San Bernard -

Amendment #19-27

October 13, 2020 Amendment #19‐27 Mr. Bruce De Terra Chief, Division of Transportation Programming Department of Transportation Transportation Programming, MS‐82 1120 “N” Street Sacramento, CA 94274‐0001 SUBJECT: AMENDMENT #19‐27 TO THE 2019 FEDERAL TRANSPORTATION IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM (FTIP) Dear Mr. De Terra: Under authority granted to me by the Southern California Association of Governments (SCAG) Regional Council, I hereby approve and transmit amendment #19‐27 for projects in Imperial, Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, and Ventura Counties. Included in this amendment package is a narrative describing the projects being amended, project listing reports, and a financial plan. No conformity determination analysis was needed for any of the projects in this amendment. This amendment: Is consistent with the Connect SoCal ‐ 2020 Regional Transportation Plan/Sustainable Communities Strategy (RTP/SCS); Does not affect the regional emissions analysis of the FTIP; Does not affect the timely implementation of the Transportation Control Measures; and Does not adversely impact financial constraint. Furthermore, SCAG through its function as the designated Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) has found the attached projects to conform to the applicable State Implementation Plan. In addition, SCAG has completed the interagency consultation and the public participation process for this amendment on October 8, 2020. No comments were received during the public review period. Page 2 Letter to Bruce De Terra October 13, 2020 If you have any questions, please contact Pablo Gutierrez of my staff at (213) 236‐1929 or via e‐mail at [email protected] Sincerely, SARAH JEPSON Director of Planning Enclosures SJ:pg cc: Mr.