The Middle Iron Age in Ulug-Depe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

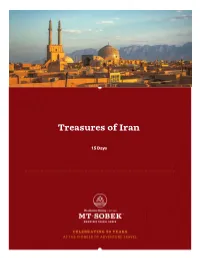

Treasures of Iran

Treasures of Iran 15 Days Treasures of Iran Home to some of the world's most renowned and best-preserved archaeological sites, Iran is a mecca for art, history, and culture. This 15-day itinerary explores the fascinating cities of Tehran, Shiraz, Yazd, and Isfahan, and showcases Iran's rich, textured past while visiting ancient ruins, palaces, and world-class museums. Wander vibrant bazaars, behold Iran's crown jewels, and visit dazzling mosques adorned with blue and aqua tile mosaics. With your local guide who has led trips here for over 23 years, be one of the few lucky travelers to discover this unique destination! Details Testimonials Arrive: Tehran, Iran “I have taken 12 trips with MT Sobek. Each has left a positive imprint on me Depart: Tehran, Iran —widening my view of the world and its peoples.” Duration: 15 Days Jane B. Group Size: 6-16 Guests "Our trip to Iran was an outstanding Minimum Age: 16 Years Old success! Both of our guides were knowledgeable and well prepared, and Activity Level: Level 2 played off of each other, incorporating . lectures, poetry, literature, music, and historical sights. They were generous with their time and answered questions non-stop. Iran is an important country, strategically situated, with 3,000+ years of culture and history." Joseph V. REASON #01 REASON #02 REASON #03 MT Sobek is an expert in Iran Our team of local guides are true This journey exposes travelers travel, with over five years' experts, including Saeid Haji- to the hospitality of Iranian experience taking small Hadi (aka Hadi), who has been people, while offering groups into the country. -

Iran in Depth

IRAN IN DEPTH In conjunction with the Near East Archaeological Foundation, Sydney University APRIL 25 – MAY 17, 2017 TOUR LEADER: BEN CHURCHER Iran in depth Overview The Persian Empire, based within modern Iran’s borders, was a significant Tour dates: April 25 – May 17, 2017 force in the ancient world, when it competed and interacted with both Greece and Rome and was the last step on the Silk Road before it Tour leader: Ben Churcher reached Europe and one of the first steps of Islam outside Arabia. In its heyday, Iran boasted lavish architecture that inspired Tamerlane’s Tour Price: $11,889 per person, twin share Samarqand and the Taj Mahal, and its poets inspired generations of Iranians and foreigners, while its famed gardens were a kind of earthly Single Supplement: $1,785 for sole use of paradise. In recent times Iran has slowly re-established itself as a leading double room nation of the Middle East. Booking deposit: $500 per person Over 23 days we travel through the spring-time mountain and desert landscapes of Iran and visit some of the most remarkable monuments in Recommended airline: Emirates the ancient and Islamic worlds. We explore Achaemenid palaces and royal tombs, mysterious Sassanian fire temples, enchanting mud-brick cities on Maximum places: 20 the desert fringes, and fabled Persian cities with their enchanting gardens, caravanserais, bazaars, and stunning cobalt-blue mosques. Perhaps more Itinerary: Tehran (3 nights), Astara (1 night), importantly, however, we encounter the unsurpassed friendliness and Tabriz (3 nights), Zanjan (2 nights), Shiraz (5 hospitality of the Iranian people which leave most travellers longing to nights), Yazd (3 nights), Isfahan (4 Nights), return. -

Qom, Náboženské Centrum Íránu

Veronika Sobotková Daniel Křížek Qom, náboženské centrum Íránu Plzeň 2016 Obsah: Úvod ................................ ................................ ................................ ................................ ................................ ................................ .. 1 Geografie ................................ ................................ ................................ ................................ ................................ ......................... 4 Historie Qomu ................................ ................................ ................................ ................................ ................................ .............. 5 1. Předislámská historie ................................ ................................ ................................ ................................ ............... 6 2. Příchod islámu do Íránu ................................ ................................ ................................ ................................ .......... 8 3. Formování ší‘itského islámu ................................ ................................ ................................ .............................. 10 4. Qom za abbásovského chalífátu ................................ ................................ ................................ ....................... 17 5. Mongolský vpád ................................ ................................ ................................ ................................ ........................ 20 6. Safíjovci ............................... -

Tehran – Tabriz – Zanjan

Code: Cu 103 Best Season : All seasons . Duration: 17 Days. Brief Tehran, Tabriz, Zanjan, Hamadan, Kashan, Yazd, Shiraz, Yasuj, Isfahan, Kashan, Tehran Day: 1 Tehran Arrivals to Tehran, meet and assist at the airport and then transfer to Hotel. Visiting Iran-e Bastan Museum (Archaeological museum) Abgine Museum. Afternoon visiting Niavaran Palace and Bazaar-e Tajrish. O/N: Tehran Iran Bastan: It is an institution formed of two complexes, including the Museum of Ancient Iran which was inaugurated in 1937, and the Museum of the (post-) Islamic Era which was inaugurated in 1972. It hosts historical monuments dating back through preserved ancient and medieval Iranian antiquities, including pottery vessels, metal objects, textile remains, and some rare books and coins. There are a number of research departments in the museum, including Paleolithic and Osteological departments, and a center for Pottery Studies. Iran Ancient Museum, the first museum in Iran at the beginning of the Street 30 July, in the western part of the drill Tehran is located on the street C-beams. Construction of the museum on 21 May 1313 and the sun on the orders of Reza Shah by French architect, Andre Godard, began. The museum building was completed in 1316 and the museum opened to the public. 5,500 square meters of land assigned to this museum, which is 2744 square meters. 1 Glassware and Ceramic Museum: is one of the museums in Tehran is. This historic house built in Qajar era and in Tehran. Avenue C bar is located. The effect on 7 Persian date Ordibehesht 1377 with registration number 2014 as one of the national monuments has been registered. -

ITINERARY §§Your Own Room Always §§Visit Amazing Destinations IRAN

§ Exclusively for Solo Travellers ITINERARY § Your Own Room Always § Visit Amazing Destinations IRAN SIMPLY PERSIA 16 DAY SOLO TOUR: SEPTEMBER 2020 www.twosacrowd.com.au IRAN 16 DAY SOLOS TOUR: 23RD SEPTEMBER - 8TH OCTOBER 2020 There’s a reason more and more people are making time to visit one of the world’s oldest civilisations. Dripping in rich history and culture, this vibrant country has an incredible mix of ethnicity, ancient monuments, bustling bazaars and intriguing landscapes. Add to this the determination of the Iranian people to welcome the world into their home, and you have an experience you’ll never forget. This fascinating Persian adventure will surprise and delight you every step of the way. You’ll spend this enchanting trip with your fellow solo travellers and, of course, your friendly ‘Two’s a Crowd’ host. So if you’re prepared for a memorable adventure and you’re after something a little different, the hidden charms of Iran could be just what you’re looking for. Will you join us? www.twosacrowd.com.au IRAN 2 IRAN 16 DAY SOLOS TOUR: 23RD SEPTEMBER - 8TH OCTOBER 2020 Day 1 - Wednesday 23rd September 2020 SHIRAZ (D) Welcome to Shiraz! You’ll be met at Shiraz airport and transferred to your hotel. Tonight we get to know our tour guide, Two’s a Crowd Tour Host and fellow travellers at the tour briefing and welcome dinner. It will be our first taste of the warm and welcoming Iranian hospitality we will experience throughout our tour. § Accommodation: Your own room at ‘Park Hotel’, in Shiraz (4 star) Day 2 - Thursday 24th September 2020 SHIRAZ (B, L) Shiraz is thought of by many to be the hub of Persian culture and our day here will be filled with feasts for all the senses. -

Les Routes Bleues : Périples D'une Couleur De La Chine À La Méditerranée

Dossier de presse Exposition temporaire Les Routes bleues : périples d'une couleur de la Chine à la Méditerranée 27 juin – 13 octobre 2014 Sommaire p. 7 Communiqué de presse p. 8 Le parcours de l'exposition p. 14 Scénographie et conception graphique p. 15 Listes des œuvres présentées p. 21 Catalogue de l'exposition p. 22 Les prêteurs p. 22 Partenaires médias et locaux p. 23 Le Musée national Adrien Dubouché p. 24 Les Portes du temps 2014 au Musée national Adrien Dubouché p. 25 Autour de l'exposition p. 26 Visuels disponibles pour la presse p. 27 Informations pratiques Visite de presse jeudi 26 juin de 10 h à 12 h Inauguration jeudi 26 juin de 18 h 30 à 21 h Contact presse Pierre Houdeline Chargé des publics et de la communication [email protected] Tél : + 33 (0)5 55 33 08 58 5 Carreau de revêtement, Iznik (Turquie), XVI e siècle Pâte siliceuse engobée, décor peint aux glaçures colorées © RMN-Grand Palais (Sèvres, Cité de la céramique) / Martine Beck-Coppola Sulook Sahand Hesamiyan, 2012 Installation : structure métallique peinte, lumières blanches © Galerie The Third Line , Dubaï 6 Communiqué de presse L’exposition Les Routes bleues : périples d'une couleur de la Chine à la Méditerranée est présentée au Musée national Adrien Dubouché du 27 juin au 13 octobre 2014. Cette exposition est l'occasion unique d'associer plus d'une centaine d’œuvres exceptionnelles – porcelaines, peintures, sculptures, textiles, bijoux et parures – issues de collections nationales prestigieuses, avec des œuvres contemporaines d'artistes de renommée internationale. Les Routes bleues se proposent de guider le voyageur sur les routes mythiques du bleu et dans les profondeurs de cette couleur fascinante, à travers l'histoire des civilisations et des matériaux. -

Iran: Persian Treasures with John Osborne 4Th – 18Th September 2017

Imam Mosque, Isfahan Iran: Persian Treasures With John Osborne 4th – 18th September 2017 The Ultimate Travel Company Escorted Tours Imam Khomeini Square, Isfahan Iran: Persian Treasures With John Osborne 4th – 18th September 2017 Contact Emily Pontifex Direct Line 020 7386 4664 Telephone 020 7386 4646 Fax 020 7386 8652 Email [email protected] John Osborne John Osborne taught classical subjects at Marlborough College for over thirty years and also worked for The British Council in Turkey and Iran. He has led several historical / cultural tours, especially to Bulgaria and Turkey but also has a great enthusiasm for Iran, having led more than a dozen specialist tours there in recent years. Detailed Itinerary Iran has played an important role throughout history, and the Persian Empire was once one of the greatest in the world. The legacy of this is all too evident today in its vibrant cities, exquisite Islamic architecture and incomparable archaeological sites. This fascinating tour offers an opportunity to explore this remarkable country and enjoy the traditional warmth and hospitality of its people. We begin in Shiraz, city of ‘roses and nightingales’, with its exquisite mosques, sacred shrines, tombs and lush rose gardens, whilst close by is the famous archaeological site of Persepolis – the city founded by Darius I and Xerxes in the 5th/6th centuries BC but razed to the ground by Alexander the Great. We also see the site of Cyrus the Great’s tomb at Pasargadae and the Achaemenid tombs at Naqsh-e-Rustam. Travelling north, we reach Yazd the centre for Iran’s small Zoroastrian community, who seeking refuge from the invading Arabs found a safe haven within its fortified walls, and we visit the Zoroastrian Fire Temple and Towers of Silence. -

L'université Pour Tous De Saint-Maur

L’UNIVERSITÉ POUR TOUS DE SAINT-MAUR et vous proposent MERVEILLES D’IRAN 12 Jours / 11 nuits 16 au 27 avril 2017 JOUR 1 PARISTEHERAN JOUR 2 TEHERAN JOUR 3 TEHERAN / KASHAN 250 km JOUR 4 KASHAN / ABYANEH / NATANZ / NAIN / YAZD 400 km JOUR 5 YAZD JOUR 6 YAZD / PASSAGARD (UNESCO) / CHIRAZ 425 km JOUR 7 CHIRAZ JOUR 8 CHIRAZ / PERSEPOLIS (UNESCO) / ISPAHAN 485 km JOUR 9 ISPAHAN JOUR 10 ISPAHAN JOUR 11 ISPAHAN / TEHERAN 425 km JOUR 12 TEHERAN PARIS 2 1ER JOUR – PARIS TEHERAN Rendez-vous des participants à l’aéroport. Envol à destination de Téhéran sur vol régulier direct Air France Arrivée à l’aéroport de Téhéran. Formalité de douane. Accueil par un guide francophone et prise en charge des bagages. Formalités douanières. Accueil et transfert à l’hôtel Logement 2EME JOUR – TEHERAN Petit déjeuner. Découverte de la ville de Téhéran : au pied des Monts Alborz, avec son agglomération, Téhéran regroupe plus de 15 millions d’habitants. C’est un véritable microcosme social, qui résume bien les différents aspects de l’Iran moderne. 3 visites de musées : à préciser Déjeuner en cours de visites Dîner Nuit à l’hôtel 3EME JOUR – TEHERAN / KACHAN Petit déjeuner. Départ à destination de Kachan. Visite de Kachan : Kashan conserve sans doute le plus bel ensemble de maisons traditionnelles d’Iran. Leur architecture s’ordonne autour de cours rectangulaires, bordées sur un ou deux étages de pièces et d’iwans, tous reliés par des passages, corridors, petites salles à coupoles ou escaliers. Visite du jardin de Fine, conçu par le grand Roi Chah Abbâs: flânerie dans ce jardin, parmi ses pavillons et son système hydraulique sophistiqué. -

The Evolution of Pottery Production During the Late Neolithic Period at Sialk on the Kashan Plain, Central Plateau of Iran*

bs_bs_banner Archaeometry ••, •• (2016) ••–•• doi: 10.1111/arcm.12258 THE EVOLUTION OF POTTERY PRODUCTION DURING THE LATE NEOLITHIC PERIOD AT SIALK ON THE KASHAN PLAIN, CENTRAL PLATEAU OF IRAN* A. K. MARGHUSSIAN† and R. A. E. CONINGHAM Department of Archaeology, Durham University, South Road, Durham DH1 3LE, UK and H. FAZELI Department of Archaeology, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran The prehistoric sherds recovered from the North Mound of Tepe Sialk were investigated using XRF, XRD and SEM/EDX analyses. These studies showed the occurrence of a gradual evolu- tion in pottery-making from the Sialk I to Sialk II periods, eventually leading to the production of bulk red pottery at the final phase of Sialk II. The relative similarity of compositions, homo- geneous microstructures and the presence of high-temperature phases demonstrated a high degree of specialization in the selection of raw materials and control of the firing temperature and atmosphere among the potters of Sialk in the sixth millennium BC, peaking at the final phase of Sialk II. KEYWORDS: SIALK, CENTRAL PLATEAU OF IRAN, NEOLITHIC POTTERY, XRD, MICROSTRUCTURE, XRF INTRODUCTION The Central Plateau of Iran is one of the most important regions for studying the prehistory of the country. The societies of the region have been at the centre of at least three millennia of sustained and continuous change and development from the sixth millennium BC on- wards, playing an active role in cultural and technical–economic development through their intra-regional and inter-regional interactions. The deep deposits of archaeological remains, reaching to ~16 m in some sites, along with the sustained progress and advancement in tech- nology and innovation, make this region very attractive for studies of the prehistoric regions of Iran. -

SUMMARY of EXPEDITION # 2 Jack Harlan's Second Seed Collecting

JACK R. HARLAN EXPEDITIONS – EXP. # 2 – IRAN, USSR & ASIA – 1960, 61 Trans Transcribed and Compiled by Harry V. Harlan, with help from Adi Damania, and others. SUMMARY OF EXPEDITION # 2 Jack Harlan’s second seed collecting expedition was to be a great trek across the Middle East, Asia and finally Ethiopia - interacting with the faculty at Alemaya University. Dr. Harlan was looking for and collecting seeds from several grasses, primarily three grasses which were introgressing in the wild: Bothriochloa ischaemum (l.) Keng, which he called “Bish”, Bothriochloa intermedia complex, which he called “Bint” and Dichanthium annulatum complex, which he called “D. ann” or “Dann”. He was interested in their hybridizing behavior at different altitudes. This was his reason for venturing into Kashmir and other mountainous regions. Dr. Jack R. Harlan flew out of the US on April 1, 1960 and spent 6 days in Europe getting ready. He began his actual expedition on April 8, 1960 in Iran at an Archaeological Expedition led by Robert Braidwood. He sojourned 74 days there and then went up to the USSR for 10 days; then traveled to Afghanistan, where he spent 26 days, traveling from west to east, collecting seeds of the grasses Bish, Bint and Dan. Then he went on to West Pakistan for 43 days, including an excursion into the Northwest Tribal areas, hunting his grasses. He even went into Pakistani administered Kashmir and Jammu area, still collecting. From West Pakistan he went to India for 94 days, total. While there he ascended into Kashmir again (the India administered side) for 7 days, came back down and ventured into the southern part of India. -

13909 Sunday APRIL 4, 2021 Farvardin 15, 1400 Sha’Aban 21, 1442

WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y 8 Pages Price 50,000 Rials 1.00 EURO 4.00 AED 42nd year No.13909 Sunday APRIL 4, 2021 Farvardin 15, 1400 Sha’aban 21, 1442 Iran rules out any Persepolis held Noruz visits to Iranian IIDCYA makes gradual lifting of by Shahr Khodro: museums falls by animations on national sanctions Page 2 IPL Page 3 one-fifth due to virusPage 6 luminaries Page 8 Joint Iran-Iraq committee to pursue Gen. Soleimani assassination Failure of decades TEHRAN - The secretary of the Iranian took place in their country and their citizens Judiciary’s High Council for Human Rights were targeted and martyred,” Baqeri Kani has said an investigation committee set said on Thursday, according to Press TV. See page 3 up jointly by Iran and Iraq will follow up General Soleimani, commander of the case of the U.S. assassination of top the Quds Force of the Islamic Revolution Iranian anti-terror commander Lieutenant Guards Corps (IRGC), and Abu Mahdi of wickedness General Qassem Soleimani. al-Muhandis, the second-in-command of Ali Baqeri Kani said that Tehran pub- Iraq’s anti-terror Popular Mobilization lic prosecutor’s office for international Units (PMU), were martyred along with offences, which is in charge of the case, their bodyguards in a U.S. drone strike is currently finalizing the indictment. authorized by former president Donald “We have started another procedure in Trump near Baghdad’s international cooperation with the Iraqis. -

Iran: Persian Treasures with Sylvie Franquet 2Nd – 16Th March 2017 and 4Th – 18Th September 2017

Imam Mosque, Isfahan Iran: Persian Treasures With Sylvie Franquet 2nd – 16th March 2017 and 4th – 18th September 2017 The Ultimate Travel Company Escorted Tours Imam Khomeini Square, Isfahan Iran: Persian Treasures With Sylvie Franquet 2nd – 16th March 2017 and 4th – 18th September 2017 Contact Emily Pontifex Direct Line 020 7386 4664 Telephone 020 7386 4646 Fax 020 7386 8652 Email [email protected] Sylvie Franquet Sylvie was born in Belgium, studied Arabic and Islamic Studies – first at Ghent University, then Cairo University – and has lived in London for more than 20 years. She has written at length about the Middle East and regularly leads trips to the region. Her newest passion is Iran, and she is now a leading expert on its culture and history. Detailed Itinerary Iran has played an important role throughout history, and the Persian Empire was once one of the greatest in the world. The legacy of this is all too evident today in its vibrant cities, exquisite Islamic architecture and incomparable archaeological sites. This fascinating tour offers an opportunity to explore this remarkable country and enjoy the traditional warmth and hospitality of its people. We begin in Shiraz, city of ‘roses and nightingales’, with its exquisite mosques, sacred shrines, tombs and lush rose gardens, whilst close by is the famous archaeological site of Persepolis – the city founded by Darius I and Xerxes in the 5th/6th centuries BC but razed to the ground by Alexander the Great. We also see the site of Cyrus the Great’s tomb at Pasargadae and the Achaemenid tombs at Naqsh-e-Rustam.