Trust in Government, Policy Effectiveness and the Governance Agenda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

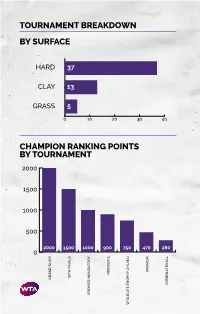

Tournament Breakdown by Surface Champion Ranking Points By

TOURNAMENT BREAKDOWN BY SURFACE HAR 37 CLAY 13 GRASS 5 0 10 20 30 40 CHAMPION RANKING POINTS BY TOURNAMENT 2000 1500 1000 500 2000 1500 1000 900 750 470 280 0 PREMIER PREMIER TA FINALS TA GRAN SLAM INTERNATIONAL PREMIER MANATORY TA ELITE TROPHY HUHAI TROPHY ELITE TA 55 WTA TOURNAMENTS BY REGION BY COUNTRY 8 CHINA 2 SPAIN 1 MOROCCO UNITED STATES 2 SWITZERLAND 7 OF AMERICA 1 NETHERLANDS 3 AUSTRALIA 1 AUSTRIA 1 NEW ZEALAND 3 GREAT BRITAIN 1 COLOMBIA 1 QATAR 3 RUSSIA 1 CZECH REPUBLIC 1 ROMANIA 2 CANADA 1 FRANCE 1 THAILAND 2 GERMANY 1 HONG KONG 1 TURKEY UNITED ARAB 2 ITALY 1 HUNGARY 1 EMIRATES 2 JAPAN 1 SOUTH KOREA 1 UZBEKISTAN 2 MEXICO 1 LUXEMBOURG TOURNAMENTS TOURNAMENTS International Tennis Federation As the world governing body of tennis, the Davis Cup by BNP Paribas and women’s Fed Cup by International Tennis Federation (ITF) is responsible for BNP Paribas are the largest annual international team every level of the sport including the regulation of competitions in sport and most prized in the ITF’s rules and the future development of the game. Based event portfolio. Both have a rich history and have in London, the ITF currently has 210 member nations consistently attracted the best players from each and six regional associations, which administer the passing generation. Further information is available at game in their respective areas, in close consultation www.daviscup.com and www.fedcup.com. with the ITF. The Olympic and Paralympic Tennis Events are also an The ITF is committed to promoting tennis around the important part of the ITF’s responsibilities, with the world and encouraging as many people as possible to 2020 events being held in Tokyo. -

Information Gathering and Public Trust Transparency Statement – 26 June 2019 Page 1 of 3

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Information Gathering and Public Trust Transparency Statement – 26 June 2019 Page 1 of 3 Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Information Gathering and Public Trust Transparency Statement Purpose The purpose of this statement is to be more transparent with New Zealanders about the kind of information gathering activity that the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (Te Papa) undertakes to give effect to our responsibilities to: protect people, information, places, and our taonga (collections); to ensure regulatory compliance; and to ensure the privacy, safety and security of the public, our visitors and staff. In December 2018 the State Services Commission issued the Model Standard for Information Gathering and Public Trust1 under Section 57(4) of the State Sector Act. This applies across the State Sector, including to Te Papa as an Autonomous Crown Entity. The Model Standard relates to information gathering associated with regulatory compliance, law enforcement and security and health and safety requirements. The purpose of the Model Standard is to ensure that government agencies use their authorities to undertake surveillance and information gathering lawfully, and in a way that respects and protects the rights and privacy of people. Transparency Statement This transparency statement explains how we collect, use and share information gathered about members of the public or other entities (directly or indirectly) in accordance with the Information Gathering Model Standards. Te Papa as the National Museum does not have any law enforcement and regulatory compliance or enforcement responsibilities, and thus does not gather any information for these purposes. -

December 2013

City House Bed & Breakfast is an elegant blend of historic beauty and modern comforts along the banks of the picturesque Susquehanna River. Providing lovely overnight accommodations, City House is also an ideal location for corporate meetings, holiday events, cocktail receptions or dinner parties. Contact us to see how City House can enhance any occasion. 915 North Front St., Hbg || 717.903.2489 || www.CityHouseBB.com CONTENTS |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| GENERAL AND LETTERS NEWS 403 N. SECOND ST. • HARRISBURG, PA 17101 7. NEWS DIGEST WWW.THEBURGNEWS.COM 10. CITY VIEW 11. STATE STREET EDITORIAL: 717.695.2576 AD SALES: 717.695.2621 IN THE BURG PUBLISHER: J. ALEX HARTZLER [email protected] 12. ARouND ToWN 20. PAST TENSE EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: LAWRANCE BINDA [email protected] SALES DIRECTOR: LAUREN MILLS [email protected] business COVER ART BY: Jason KREIGER www.BRAINVessel.com SENIOR WRITER: Paul BARkER 24. FACE oF BuSINESS [email protected] 25. NEW BIz 26. SHoP WINDoW SALES/SPECIAL Projects: ANDREA Black LETTER FROM THE EDITOR [email protected] The holidays, like so many things in this country, have become an occasion for irresponsible CONTRIBUTORS: GOOD EATS media to set people against one another. TARA LEO AUCHEy, today’S THE day HARRISBURG 28. HoME C ooKING At TheBurg, we say the heck with the [email protected] 30. WINE TIME manufactured divisions that help no one Rosemary RUGGIERI BAER but a few thoughtless cable news hosts and [email protected] politicians who are trying to get attention and sell books. We think that most people, BARBARA TRAININ BLANk HOME FRONT regardless of their traditions and beliefs, can [email protected] agree that their holidays involve two things— Jess HAyDEN 32. -

Chapter 2. Public Sector Whistleblower Protection Laws in OECD Countries

2. PUBLIC SECTOR WHISTLEBLOWER PROTECTION LAWS IN OECD COUNTRIES – 39 Chapter 2. Public sector whistleblower protection laws in OECD countries The purpose of whistleblower protection is to protect individuals from being exposed and retaliated against for disclosing misconduct. Despite the common aim of whistleblower protection systems, the disclosure processes in place in OECD countries vary. This chapter analyses the varying elements and protections that countries have put in place and how they apply throughout disclosure processes, including: the scope of coverage and subject matter; reporting requirements; channels of reporting; fundamental safeguards, such as anonymity and confidentiality; and the prospect of incentives. The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law. COMMITTING TO EFFECTIVE WHISTLEBLOWER PROTECTION © OECD 2016 40 – 2. PUBLIC SECTOR WHISTLEBLOWER PROTECTION LAWS IN OECD COUNTRIES Upon identifying wrongdoing or the attempt to commit wrongdoing, an employee may not be certain of what to do with the information discovered, where or whom to turn to, and whether they are protected by relevant whistleblower protection mechanisms. Throughout the disclosure process, employees may have reservations about safeguards such as anonymity and confidentiality measures, they may also be incentivised by the prospect of a reward. The multitude of steps along the disclosure process can be daunting and vague, however, if implemented according to whistleblower protection laws, the disclosure process can and should be the first system in line to protect whistleblowers from reprisal. -

Eurobarometer 513 Climate Change

Special Eurobarometer 513 Climate Change Report Fieldwork: March - April 2021 This document does not represent the point of view of the European Commission. The interpretations and opinions contained in it are solely those of the authors. Project title Special Eurobarometer 513 Climate, Report Language version EN Catalogue number ML-03-21-256-EN-N ISBN 978-92-76-38399-4 DOI 10.2834/437 © European Union, 2021 https://www.europa.eu/eurobarometer Photo credit: Getty Images Special Eurobarometer 513 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 7 I. EUROPEAN PERCEPTIONS OF CLIMATE CHANGE 8 1. Perceptions of climate change as a global problem 9 2. Perceived seriousness of climate change 22 II. TAKING ACTION TO TACKLE CLIMATE CHANGE 26 1. Responsibility for tackling climate change 27 2. Personal action to tackle climate change 34 3. Types of individual action 39 III. ATTITUDES TO FIGHTING CLIMATE CHANGE AND THE TRANSITION TO CLEAN ENERGIES 49 1. Attitudes towards taking action on climate change 51 2. Attitudes towards reducing fossil fuel imports 54 3. Attitudes towards the economic benefits of promoting EU expertise in clean technologies outside the EU 57 4. Attitudes to public financial support for clean energies as opposed to fossil fuel subsidies 60 5. Attitudes to adapting to the adverse impacts of climate change 64 6. Attitudes to tackling climate change and environmental issues as a priority to improve public health 67 7. Attitudes on the trade-off between costs caused by climate change versus the costs of a green transition 69 IV. LOOKING TO THE FUTURE 72 1. Current national governments action to tackle climate change 73 2. -

2020 Women’S Tennis Association Media Guide

2020 Women’s Tennis Association Media Guide © Copyright WTA 2020 All Rights Reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced - electronically, mechanically or by any other means, including photocopying- without the written permission of the Women’s Tennis Association (WTA). Compiled by the Women’s Tennis Association (WTA) Communications Department WTA CEO: Steve Simon Editor-in-Chief: Kevin Fischer Assistant Editors: Chase Altieri, Amy Binder, Jessica Culbreath, Ellie Emerson, Katie Gardner, Estelle LaPorte, Adam Lincoln, Alex Prior, Teyva Sammet, Catherine Sneddon, Bryan Shapiro, Chris Whitmore, Yanyan Xu Cover Design: Henrique Ruiz, Tim Smith, Michael Taylor, Allison Biggs Graphic Design: Provations Group, Nicholasville, KY, USA Contributors: Mike Anders, Danny Champagne, Evan Charles, Crystal Christian, Grace Dowling, Sophia Eden, Ellie Emerson,Kelly Frey, Anne Hartman, Jill Hausler, Pete Holtermann, Ashley Keber, Peachy Kellmeyer, Christopher Kronk, Courtney McBride, Courtney Nguyen, Joan Pennello, Neil Robinson, Kathleen Stroia Photography: Getty Images (AFP, Bongarts), Action Images, GEPA Pictures, Ron Angle, Michael Baz, Matt May, Pascal Ratthe, Art Seitz, Chris Smith, Red Photographic, adidas, WTA WTA Corporate Headquarters 100 Second Avenue South Suite 1100-S St. Petersburg, FL 33701 +1.727.895.5000 2 Table of Contents GENERAL INFORMATION Women’s Tennis Association Story . 4-5 WTA Organizational Structure . 6 Steve Simon - WTA CEO & Chairman . 7 WTA Executive Team & Senior Management . 8 WTA Media Information . 9 WTA Personnel . 10-11 WTA Player Development . 12-13 WTA Coach Initiatives . 14 CALENDAR & TOURNAMENTS 2020 WTA Calendar . 16-17 WTA Premier Mandatory Profiles . 18 WTA Premier 5 Profiles . 19 WTA Finals & WTA Elite Trophy . 20 WTA Premier Events . 22-23 WTA International Events . -

FOMC Rules and Authorizations -- As of January 29, 2013

Federal Reserve System Federal Open Market Committee Rules and Authorizations January 2013 Table of Contents FOMC Rules, Statements, and Resolutions .................................................................................. 4 Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy ....................................................... 4 FOMC Rules of Organization ........................................................................................................... 5 FOMC Rules of Procedure ................................................................................................................ 7 Open Market Operations of Federal Reserve Banks ....................................................................... 10 Procedures for Allocation of Securities in the System Open Market Account ................................ 12 Resolution Authorizing Certain Actions by Federal Reserve Banks During an Emergency ........... 13 Guidelines for the Conduct of System Open Market Operations in Federal-Agency Issues ........... 14 Temporary Authority to Operate System Account .......................................................................... 15 FOMC Rules Regarding the Availability of Information ................................................................ 16 FOMC Policy on External Communications of Committee Participants ........................................ 24 FOMC Policy on External Communications of Federal Reserve System Staff .............................. 26 FOMC Statements of Policy ........................................................................................................... -

EFAMRO / ESOMAR Position Statement on the Proposal for an Eprivacy Regulation —

EFAMRO / ESOMAR Position Statement on the Proposal for an ePrivacy Regulation — April 2017 EFAMRO/ESOMAR Position Statement on the Proposal for an ePrivacy Regulation April 2017 00. Table of contents P3 1. About EFAMRO and ESOMAR 2. Key recommendations P3 P4 3. Overview P5 4. Audience measurement research P7 5. Telephone and online research P10 6. GDPR framework for research purposes 7. List of proposed amendments P11 a. Recitals P11 b. Articles P13 2 EFAMRO/ESOMAR Position Statement on the Proposal for an ePrivacy Regulation April 2017 01. About EFAMRO and ESOMAR This position statement is submitted In particular our sector produces research on behalf of EFAMRO, the European outcomes that guide decisions of public authorities (e.g. the Eurobarometer), the non- Research Federation, and ESOMAR, profit sector including charities (e.g. political the World Association for Data, opinion polling), and business (e.g. satisfaction Research and Insights. In Europe, we surveys, product improvement research). represent the market, opinion and In a society increasingly driven by data, our profession ensures the application of appropriate social research and data analytics methodologies, rigour and provenance controls sectors, accounting for an annual thus safeguarding access to quality, relevant, turnover of €15.51 billion1. reliable, and aggregated data sets. These data sets lead to better decision making, inform targeted and cost-effective public policy, and 1 support economic development - leading to ESOMAR Global Market Research 2016 growth and jobs. 02. Key Recommendations We support the proposal for an ePrivacy Amendment of Article 8 and Recital 21 to enable Regulation to replace the ePrivacy Directive as research organisations that comply with Article this will help to create a level playing field in a true 89 of the General Data Protection Regulation European Digital Single Market whilst increasing (GDPR) to continue conducting independent the legal certainty for organisations operating in audience measurement research activities for different EU member states. -

Scanned Using Fujitsu 6670 Scanner and Scandall Pro Ver

2002/33 Securities Act (Trustee Companies) Exemption Amendment Notice 2002 Pursuant to the Securities Act 1978, the Securities Commission gives the following notice. Contents 1 Title 6 Exemption from sections 33(3) and 2 Commencement 37(3) 3 Amendment to Title of principal 7 Exemption from section 52(1) and notice (3) 4 Interpretation 8 Exemption from section 54 5 Application of notice Notice 1 Title (1) This notice is the Securities Act (Trustee Companies) Exemp tion Amendment Notice 2002. (2) In this notice, the Securities Act (Trustee Companies) Exemp tion Notice 1997 1 is called "the principal notice". I SR 19971270 2 Commencement This notice comes into force on 1 March 2002. 3 Amendment to Title of principal notice Clause 1(1) of the principal notice is amended by omitting the words "Trustee Companies", and substituting the words "Group Investment Funds" . 4 Interpretation (1) Clause 2( 1) of the principal notice is amended by revoking the definition of Fund, and substituting the following definition: 136 Securities Act (Trustee Companies) 200213:1 Exemption Amendment Notice 2002 cl 8 "Fund means a Group Investment Fund established under "(a) section 29 of the Trustee Companies Act 1967; or "(b) section 63 of the Public Trust Act 2001; or "(c) section 42A of the Public Trust Office Act 1957". (2) Clause 2( 1) of the principal notice is amended by revoking the definition of trustee company, and substituting the following definition: "trustee means- "(a) a trustee company within the meaning of the Trustee Companies Act 1967 and that is named in Schedule 1: "(b) Public Trust." 5 Application of notice Clause 2A of the principal notice is amended by revoking subclause (1), and substituting the following subclause: "( 1) This notice applies only to qualifying participatory securities for which a prospectus is registered on or before 31 March 2002. -

The "Public Trust" As It Is Used in Article VI

THE "PUBIC TRUST" JenniferAnglim Kreder ABSTRACT It seems as if no one really knows the meaning of the term "public Trust" used in the Religious Test Clause of Article VI of the U.S. Constitution. 7iis Article is the first scholarly attempt to define the term by exploring historical evidence pre-dating the nation's jounding through the Constitution's adoption, including British and colonial trust law that influenced the Founders' conception of the term. Today, one can find the term used only in the cases and scholarship concerning environmental law, tax law and museum law. After a thorough analysis of the old and new sources, this Article proposes the following original definition of term "public Trust": "Any entity given special privilege by the government, beyond the simple grant of a state corporate charteroften coupled with state or federal tax waivers, so long as that entity is legally obligated to engage in conduct that could traditionally have been performed by the government itself for the public's benefit." TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ..................................... ..... 1426 I. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF ARTICLE VI............ .... 1428 A. The Stuart Period & Colonial Era......... ............... 1429 B. The Foundingand Early Republic ................... 1430 C. InterpretationalFoundations .................. ..... 1434 D. Fiduciary Underpinnings .......................... 1438 II. MODERN SIGNIFICANCE OF THE PUBLIC TRUST....... ..... 1440 A. Judicially Recognized Trusts and Non-Profit Corporations.. 1441 B. EnvironmentalRegulation ......................... 1443 1. Historical Origins of the Environmental "PublicTrust * Professor of Law, Salmon P. Chase College of Law. The author wishes to disclose that she has done a limited amount of legal work for American Atheists, Inc., including in Ameri- can Atheists, Inc. -

Solvay 224 Avenue Louise 1050 Brussels

Mobilise! Incorporating Mobile Phones in Social and Policy-oriented Surveys ALEC M GALLUP FUTURE OF 1SURVEY RESEARCH FORUM 14 October, 2009 Hôtel Solvay 224 Avenue Louise 1050 Brussels % Dear Attendee, Mobile phones have had a remarkable impact on the world in a relatively short period of time. In all surveys, the overriding consideration is to reach all members of the public, young or old, male or female, employed or self- employed. In the nineties, fixed-line telephone coverage reached almost saturation point, but times are changing. In Europe, countries such as Finland and the Czech Republic now have a majority of citizens who are "mobile-only". Furthermore, as mobile phone ownership and usage is currently higher among certain groups, such as younger members of the population, the potential arises for mobile-phone non- coverage bias. This was a topic widely debated during the 2004 US Presidential election. Further discussion and research on the topic is vital. That's why Gallup has brought together the world's leading experts to thrash out issues that will undoubtedly impact the future of social research. Earlier this year, we were saddened by the death of Alec Gallup, a consummate polling professional who served the company for 60 years. If he was still with us, he would be watching the increase of the mobile-phone population with interest. Alec Gallup understood polling from A to Z and he knew that that the future of survey research depended on methodologies that would continue to give an equal opportunity of being polled … to all members of the public Bi-annual series of seminars: Future of Surveys We would therefore like to welcome you to "The 1st Alec Gallup Future of Survey Research Forum: Incorporating Mobile Phones in Social and Policy-oriented Surveys. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae PATRICK JOSEPH LUCEY (PhD) • Email: [email protected] • Website: www.patricklucey.com RESEARCH INTERESTS Artificial Intelligence, Sports Analytics, Machine Learning, Computer Vision, Multi-Agent Systems, Affective Computing, Video Analytics, Spatiotemporal Data Mining, Unstructured Data Analytics PROFESSIONAL PREPARATION • 2004 - 2008(Feb) - Ph.D., Speech, Audio, Image and Video Technology Laboratory, Faculty of Built Engineering and Environment, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia. (Dissertation Title: “Lipreading Across Multiple Views” [Nominated for Outstanding Thesis Award]) • 2000 - 2003 - B.Eng., Electrical and Electronic Engineering (1st class honors - GPA 6.66 out of 7), University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, Australia, 2003 (Undergraduate Thesis Title: “Algorithms for Face Recognition”) RESEARCH EXPERIENCE • 2015(Oct) - Present - Director of Data Science, STATS, Chicago, IL, USA. • 2013(Sept) - 2015(Sept) - Associate Research Scientist, Disney Research Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA. • 2009 - Present - Research Project Coordinator (Adjunct), Queensland University of Technology (SAIVT Laboratory), Brisbane, Australia. (Supervise PhD students) • 2010(Nov) - 2013(Aug) - Postdoctoral Associate, Disney Research Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA. • 2009(Jan) - 2010 (Oct) - Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Robotics Institute, Carnegie Mellon University/ Department of Psychology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA. (Working on automatically detecting pain, depression and facial paralysis