The Mediated Sentencing of Metiria Turei

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report for the Year Ended 30 June 2012

A.2 Annual Report for the year ended 30 June 2012 Parliamentary Service Commission Te Komihana O Te Whare Pāremata Presented to the House of Representatives pursuant to Schedule 2, Clause 11 of the Parliamentary Service Act 2000 About the Parliamentary Service Commission The Parliamentary Service Commission (the Commission) is constituted under the Parliamentary Service Act 2000. The Commission has the following functions: • to advise the Speaker on matters such as the nature and scope of the services to be provided to the House of Representatives and members of Parliament; • recommend criteria governing funding entitlements for parliamentary purposes; • recommend persons who are suitable to be members of the appropriations review committee; • consider and comment on draft reports prepared by the appropriations review committees; and • to appoint members of the Parliamentary Corporation. The Commission may also require the Speaker or General Manager of the Parliamentary Service to report on matters relating to the administration or the exercise of any function, duty, or power under the Parliamentary Service Act 2000. Membership The membership of the Commission is governed under sections 15-18 of the Parliamentary Service Act 2000. Members of the Commission are: • the Speaker, who also chairs the Commission; • the Leader of the House, or a member of Parliament nominated by the Leader of the House; • the Leader of the Opposition, or a member of Parliament nominated by the Leader of the Opposition; • one member for each recognised party that is represented in the House by one or more members; and • an additional member for each recognised party that is represented in the House by 30 or more members (but does not include among its members the Speaker, the Leader of the House, or the Leader of the Opposition). -

Issue 17 2017

Shifting Stones Ruckus over Ruggers Centre Stage Catriona Britton examines the harm being done Mark Fullerton talks SKY TV’s very bad A chat with New Zealand theatre company to an historical site manners Indian Ink [1] ISSUE SEVENTEEN CONTENTS 7 NEWS 10 COMMUNITY MED STUDENTS SICK OF LOAN CAP THE LIMITS OF FREEDOM OF SPEECH Medical students aren’t getting graduation caps because of A look at how New Zealand student loan caps deals with censorship 13 LIFESTYLE 16 FEATURES SPRING AWAKENING TIT FOR TATT We’ve got tips on how to make your garden bloomin’ beautiful Olivia Stanley ponders society’s this Spring view of tattoos 31 ARTS 34 COLUMNS ONE MOVIE TO RULE THEM ALL A SHADOW OF HER FORMER SELF A definitive ranking of the LOTR and Hobbit movie Caitlin Abley has had a gutsful trilogies of Shadows cuisine New name. Same DNA. ubiq.co.nz 100% Student owned - your store on campus [3] NOTICE OF POLLING TIMES FOR THE 2018 AUSA EXECUTIVE & 2017 ENVIRONMENTAL AFFAIRS OFFICER ELECTIONS ONLINE ELECTIONS WILL BE HELD FROM 9AM ON TUESDAY 22ND TO 4PM ON THURSDAY 24TH OF AUGUST 2017 TO VOTE GO TO: WWW.AUSA.ORG.NZ/VOTE ONLY AUSA MEMBERS CAN VOTE, HOWEVER YOU CAN SIGN UP ONLINE WHEN YOU VOTE. A POLLING BOOTH WILL BE AVAILABLE AT AUSA RECEPTION IF YOU DO NOT HAVE ACCESS TO ONLINE VOTING. LIFE MEMBERS WILL NEED TO GO TO AUSA RECEPTION TO VOTE. BOB LACK AUSA RETURNING OFFICER NOTICE OF POLLING TIMES FOR THE EDITORIAL 2018 AUSA EXECUTIVE Catriona Britton Samantha Gianotti & 2017 ENVIRONMENTAL AFFAIRS OFFICER ELECTIONS Giving a Shit ONLINE ELECTIONS WILL BE HELD FROM 9AM ON TUESDAY 22ND Last Monday morning, one Craccum Editor was make it into the top ten that God cast down on with deliberation and confidence. -

Download Download

New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 45(1): 14-30 Minor parties, ER policy and the 2020 election JULIENNE MOLINEAUX* and PETER SKILLING** Abstract Since New Zealand adopted the Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) representation electoral system in 1996, neither of the major parties has been able to form a government without the support of one or more minor parties. Understanding the ways in which Employment Relations (ER) policy might develop after the election, thus, requires an exploration of the role of the minor parties likely to return to parliament. In this article, we offer a summary of the policy positions and priorities of the three minor parties currently in parliament (the ACT, Green and New Zealand First parties) as well as those of the Māori Party. We place this summary within a discussion of the current volatile political environment to speculate on the degree of power that these parties might have in possible governing arrangements and, therefore, on possible changes to ER regulation in the next parliamentary term. Keywords: Elections, policy, minor parties, employment relations, New Zealand politics Introduction General elections in New Zealand have been held under the Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) system since 1996. Under this system, parties’ share of seats in parliament broadly reflects the proportion of votes that they received, with the caveat that parties need to receive at least five per cent of the party vote or win an electorate seat in order to enter parliament. The change to the MMP system grew out of increasing public dissatisfaction with certain aspects of the previous First Past the Post (FPP) or ‘winner-take-all’ system (NZ History, 2014). -

A Politics and the Campaign

Notes Resources Processor Time 00:00:00.24 Elapsed Time 00:00:00.00 Frequency Table jinterest A1: how interested in politics Frequency Percent Valid Percent Valid Very interested 412 16.7 16.7 16.7 Fairly interested 1157 46.8 47.0 63.7 Slightly interested 769 31.1 31.2 94.9 Not at all interested 125 5.0 5.1 100.0 Total 2463 99.5 100.0 Missing System 12 .5 Total 2475 100.0 jrefbefore A2: knowledge of referendum before the fact Frequency Percent Valid Percent Valid Yes 2192 88.6 89.3 89.3 No 167 6.7 6.8 96.1 Don't know 95 3.8 3.9 100.0 Total 2453 99.1 100.0 Missing System 22 .9 Total 2475 100.0 Frequency Percent Valid Percent Valid Yes 2041 82.5 83.3 83.3 No 300 12.1 12.2 95.6 Don't know 108 4.4 4.4 100.0 Total 2449 99.0 100.0 Missing System 26 1.0 Total 2475 100.0 jintnt_work A4: access to the Internet at work Frequency Percent Valid Percent Valid 0 1444 58.3 58.3 58.3 Internet access at work 1031 41.7 41.7 100.0 Total 2475 100.0 100.0 jintnt_home A4: access to the Internet at home Frequency Percent Valid Percent Valid 0 524 21.2 21.2 21.2 Internet access at home 1951 78.8 78.8 100.0 Total 2475 100.0 100.0 Page 3 jintnt_mob A4: access to the Internet on a mobile device Frequency Percent Valid Percent Valid 0 1843 74.5 74.5 74.5 632 25.5 25.5 100.0 Total 2475 100.0 100.0 jintnt_else A4: access to the Internet somewhere else Frequency Percent Valid Percent Valid 0 2345 94.7 94.7 94.7 130 5.3 5.3 100.0 Total 2475 100.0 100.0 jintnt_none A4: no access to the Internet Frequency Percent Valid Percent Valid 0 2096 84.7 84.7 84.7 No Internet access -

Sailing in a New Direction ■■Page 5

SEPTEMBER 2017 The University of Auckland News for Staff Vol 46/ Issue 07 /September 2017 SAILING IN A NEW DIRECTION ■ PAGE 5 INSIDE A 700-plus page biography and Collected Poems of New Zealand literary heavyweight Allen Curnow, pictured above, by the late Emeritus Professor Terry Sturm is being launched this month by Auckland University Press. PAGE 5 COUNTING THE VOTES THE TAX QUESTION TOURIST IN HER OWN Just like Brexit and the 2016 US election, in the None of our political parties are dealing with COUNTRY upcoming General Election on 23 September the basic inequities of the current tax system, This month’s My Story, Samantha Perry, is every vote will definitely count, writes political says tax specialist Mark Keating. looking forward to going back to her family’s scientist Jennifer Lees-Marshment. roots in Sri Lanka in September. PAGE 12 PAGE 9 PAGE 6 SNAPSHOT CONTENTS TOP PRIZE FOR WATERCOLOUR WHAT’S NEW ............................ 3 In 1999 a generous bequest to create a IN BRIEF .................................... 4 scholarship to ‘foster interest in New Zealand COVER STORY ............................. 5 watercolour’ established the country’s largest art prize for the medium, the Henrietta and Lola DID YOU KNOW? ......................... 7 Anne Tunbridge Scholarship, worth $10,000. Awarded annually to an Elam School of Fine Arts WHAT’S ON CAMPUS .................. 7 student, this year the prize was jointly shared RESEARCH IN FOCUS .................. 8 between undergraduate Honor Hamlet and postgraduate Scarlett Cibilich from dozens of WHAT AM I DISCOVERING ............ 9 entries. The Tunbridge’s foresight continues to strengthen the medium’s appeal. Right, detail IN THE SPOTLIGHT ..................... -

Ensuring New Zealand's Constitution Is Fit for Purpose

July 2013 Submission Ensuring New Zealand’s Constitution is Fit for Purpose Submission to the Constitutional Advisory Panel ΞDĐ'ƵŝŶŶĞƐƐ/ŶƐƟƚƵƚĞ>ŝŵŝƚĞĚϮϬϭϯ /^EϵϳϴͲϭͲϵϳϮϭϵϯͲϯϳͲϮ;ƉĂƉĞƌďĂĐŬͿ /^EϵϳϴͲϭͲϵϳϮϭϵϯͲϯϴͲϵ;W&Ϳ WKŽdžϮϰϮϮϮ tĞůůŝŶŐƚŽŶϲϭϰϮ EĞǁĞĂůĂŶĚ ǁǁǁ͘ŵĐŐƵŝŶŶĞƐƐŝŶƐƟƚƵƚĞ͘ŽƌŐ ďŽƵƚƚŚĞDĐ'ƵŝŶŶĞƐƐ/ŶƐƟƚƵƚĞ The McGuinness Institute is a non-partisan, not-for-profit research organisation specialising in issues that affect New Zealand’s long term future. Founded in 2004, the Institute aims to contribute to the ongoing debate about how to progress this nation through the production of timely, comprehensive and evidence-based research and the sharing of ideas. This can take a number of forms including books, reports, working papers, think pieces, workshops and videos. ďŽƵƚƚŚĞƵƚŚŽƌ Wendy McGuinness Wendy McGuinness is the founder and chief executive of the McGuinness Institute. Originally from the King Country, Wendy completed her secondary schooling at Hamilton Girls’ High School and Edgewater College. She then went on to study at Manukau Technical Institute (gaining an NZCC), Auckland University (BCom) and Otago University (MBA), as well as completing additional environmental papers at Massey University. As a Fellow Chartered Accountant (FCA) specialising in risk management, Wendy has worked in both the public and private sectors. In 2004 she established the McGuinness Institute (formerly the Sustainable Future Institute) as a way of contributing to New Zealand’s long-term future. She has also co-authored a book, Nation Dates: Significant events that have shaped the nation of New Zealand. tŝƚŚŽŶƚƌŝďƵƟŽŶƐĨƌŽŵ Sylvia Avery Sylvia Avery is a practicing primary school teacher who recently graduated from the University of Otago with a BA in Theatre and Politics and a Graduate Diploma in Teaching (Primary). -

W Omen Talking Politics

The Research Magazine of the New Zealand Political Studies Association (NZPSA) December 2017 Talking Politics Talking Women ISSN: 1175-1542 wtp Contents From the Editors 3 Reflections Priya Kurian and Gauri Nandedkar, The Efficacy of Non-Violence in a Post-Truth Age 24 University of Waikato Greta Snyder, Victoria University of Wellington New Zealand Election 2017 5 Changing Climate, Changing Self 26 Crystal Tawhai, University of Waikato From the President The New Zealand General Election 2017: Vote, Vote Against the Buying of the Fight 28 A Win for Women’s Representation 5 Julie Nevin, Massey University Jennifer Curtin, President of the NZPSA, University of Auckland Research Briefs 29 Meaningful Representation: Where is the Ethnic Minority Voice in New Zealand Politics? 7 Local Ownership of Energy Assets in New Zealand 29 Anjum Rahman, Former candidate Julie MacArthur and Anna L. Berka, for central and local government University of Auckland Rational Russia: A Neoclassical Realist Articles 9 Approach to Russian Foreign Policy and the Annexation of Crimea 30 Women and the 2016 Elections 9 Kirstin Bebell, University of Otago Jean Drage, Lincoln University Evidence for the Need of Policy to Better Address TV and Film Reviews 31 Child Income Poverty and Material Hardship in New Zealand 12 A Handmaid’s Tale (2017) 31 Bianca Rogers-Mott, University of Waikato Estelle Townshend-Denton, University of Waikato Trafficking of Women for Sexual Slavery and its 20th Century Women (2016) 34 Prevention: A Feminist Critique of the Criminalisation Georgia Kahan, Victoria University of Wellington of Demand as an Effective Measure to Prevent Women’s Trafficking 14 Natalia Bogado, University of Auckland Recent Publications 35 Toleration in Comparative Perspective 35 The War-Peace Continuum of Sexual and Gender-based Violence: An Age Old Malady of Vicki A. -

Journalism, Online Critique and the Political Resignation of Metiria Turei

Phelan & Salter (2019): preprint of article published online March 18, 2019 in Journalism: Theory, Practice and Criticism “Just doing their job?” Journalism, online critique and the political resignation of Metiria Turei Sean Phelan Massey University, New Zealand [email protected] Leon A Salter Massey University, New Zealand [email protected] *Please cite published version at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1464884919834380 (The published version has some minor copyediting differences and corrections, and is available on request from the authors) Abstract When Metiria Turei resigned as co-leader of the Green party of Aotearoa New Zealand in August 2017, there was clear disagreement about the role played by journalism in her resignation. The controversy began after Turei confessed to not disclosing full information to the authorities about her personal situation as a welfare recipient in the 1990s. Journalists insisted they were simply “doing their job” by interrogating Turei’s story, while online supporters accused the media of hounding her. This paper examines the media politics of the controversy by putting Carlson’s concept of metajournalistic discourse into theoretical conversation with Laclau and Mouffe’s discourse theory, especially their concept of antagonism. We explore what the case says about traditional journalistic authority in a media system where journalism is increasingly vulnerable to online critique from non-journalists. Keywords: Antagonism, discourse theory, metajournalistic discourse, opinion journalism, New Zealand politics, social media, online critique. 1 Phelan & Salter (2019): preprint of article published online March 18, 2019 in Journalism: Theory, Practice and Criticism Introduction On July 16 2017, Metiria Turei, the co-leader of the Green Party of Aotearoa New Zealand, gave a speech to the party’s annual general meeting that outlined “radical” (Davison, 2017a) welfare reform policies ahead of the country’s September general election. -

Political Messaging, Parliament, and People, Or, Why Politicians Say The

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Political Messaging, Parliament, and People Or, Why Politicians Say the Things They Do the Way They Do: The Parliamentary Green Party of Aotearoa New Zealand in 2013 A thesis presented in partial fulfilment Of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Social Anthropology At Massey University Palmerston North Aotearoa New Zealand Jessica Anne Copplestone Bignell 2018 Abstract One of the main things a Member of Parliament (MP) does in their everyday work is talk. They are constantly saying things to try to win over the public’s support and make the world they envision real. This thesis is about politicians’ statements: why they say the things they say the way they do. Based on behind-the-scenes ethnographic fieldwork in the parliamentary offices of the Green Party of Aotearoa New Zealand, I explore the difficult strategic work that shapes what opposition MPs say. In order to win over the public support they need to increase their vote, MPs have to communicate effectively in adherence to the rules and codes of political messaging, be good oppositional MPs, and speak and act in ways that fit authentically with their dispositions. I show that, unlike the simple soundbites we see in public from our politicians, the production of statements designed to win support is messy, indeterminate, uncertain, filled with tension and – above all – intensely complex. -

Roll of Members of the New Zealand House of Representatives, 1854 Onwards

Roll of members of the New Zealand House of Representatives, 1854 onwards Sources: New Zealand Parliamentary Record, Newspapers, Political Party websites, New Zealand Gazette, New Zealand Parliamentary Debates (Hansard), Political Party Press Releases, Appendix to the Journal of the House of Representatives, E.9. Last updated: 17 November 2020 Abbreviations for the party affiliations are as follows: ACT ACT (Association of Consumers and Taxpayers) Lib. Liberal All. Alliance LibLab. Liberal Labour CD Christian Democrats Mana Mana Party Ch.H Christian Heritage ManaW. Mana Wahine Te Ira Tangata Party Co. Coalition Maori Maori Party Con. Conservative MP Mauri Pacific CR Coalition Reform Na. National (1925 Liberals) CU Coalition United Nat. National Green Greens NatLib. National Liberal Party (1905) ILib. Independent Liberal NL New Labour ICLib. Independent Coalition Liberal NZD New Zealand Democrats Icon. Independent Conservative NZF New Zealand First ICP Independent Country Party NZL New Zealand Liberals ILab. Independent Labour PCP Progressive Coalition ILib. Independent Liberal PP Progressive Party (“Jim Anderton’s Progressives”) Ind. Independent R Reform IP. Independent Prohibition Ra. Ratana IPLL Independent Political Labour League ROC Right of Centre IR Independent Reform SC Social Credit IRat. Independent Ratana SD Social Democrat IU Independent United U United Lab. Labour UFNZ United Future New Zealand UNZ United New Zealand The end dates of tenure before 1984 are the date the House was dissolved, and the end dates after 1984 are the date of the election. (NB. There were no political parties as such before 1890) Name Electorate Parl’t Elected Vacated Reason Party ACLAND, Hugh John Dyke 1904-1981 Temuka 26-27 07.02.1942 04.11.1946 Defeated Nat. -

How Is Co-Leadership Enacted in the Green Party of Aotearoa New Zealand

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. 09095616 Neil Miller How is co-leadership enacted in the Green Party of Aotearoa New Zealand? A 152.800 thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Management at Massey University NEIL JAMES MILLER 09095616 22 February 2015 Word count: 29,080 MILLER, Neil 090951616 ABSTRACT This research report explores the enactment of a gender-balanced co-leadership throughout the organisation of the Green Party of Aotearoa New Zealand. This small-sized political organisation has had representatives in parliament since 1996. Its experimental model of a male and a female sharing positions arose out of the social movements of the baby boomer generation. Gender-balanced co-leadership was devised as an exception to the norm of a single leader (frequently presented as a heroic man). The metaphor of theatre is used to frame a description of the stage-managed performance of Green Party political co-leaders. I show how co-leaders have been portrayed over the life span of the party as if they were characters in play. The re-presentation of co-leaders is illustrated by images, primarily taken from the party magazine. Experiences of the enactment of this co-leader model are interpreted through five interviews with key informants who have all held formal positions of authority within the organisation. -

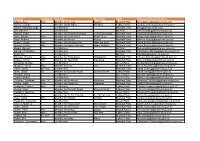

Grid Export Data

Contact Salutation Job Title Electorate Party Parliament Email (Contact) Adams, Amy Hon Member for Selwyn Selwyn National Party [email protected] Ardern, Jacinda Member for Mt Albert Mt Albert Labour Party [email protected] Bakshi, Kanwaljit Singh List Member National Party [email protected] Ball, Darroch List Member NZ First [email protected] Barclay, Todd Member for Clutha-Southland Clutha-Southland National Party [email protected] Barry, Maggie Hon Member for North Shore North Shore National Party [email protected] Bayly, Andrew Member for Hunua Hunua National Party [email protected] Bennett, David Hon Member for Hamilton East Hamilton East National Party [email protected] Bennett, Paula Hon Member for Upper Harbour Upper Harbour National Party [email protected] Bindra, Mahesh List Member NZ First [email protected] Bishop, Christopher List Member National Party [email protected] Bond, Ria List Member NZ First [email protected] Borrows, Chester Hon Member for Whanganui Whanganui National Party [email protected] Bridges, Simon Hon Member for Tauranga Tauranga National Party [email protected] Browning, Steffan List Member Green Party [email protected] Brownlee, Gerry Hon Member for Ilam Ilam National Party [email protected] Carter, David Rt. Hon. List Member National Party [email protected] Clark, David Dr. Member for Dunedin North Dunedin North Labour Party [email protected] Clendon, David List Member Green Party [email protected] Coates, Robert List Member Green Party [email protected] Coleman, Jonathan Hon.