DNA Sequencing Link: DNA Sequencing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Living Being's Finished Arrangement of DNA

e in G net ts ic n E e n g m i e n c e e n r a i v n d g A ISSN: 2169-0111 Advancements in Genetic Engineering Editorial Living Being's Finished Arrangement of DNA Bahman Hosseini* Department of Horticulture, Faculty of Agriculture, Urmia University, Iran INTRODUCTION MS2 coat protein work, deciding the total nucleotide-succession of bacteriophage MS2-RNA (whose genome encodes only four Genomics is an interdisciplinary field of science zeroing in on qualities in 3569 base sets [bp]) and Simian infection 40 out of the construction, work, advancement, planning, and altering of 1976 and 1978, individually. genomes. A genome is a living being's finished arrangement of DNA, including the entirety of its qualities. Rather than Notwithstanding his fundamental work on the amino corrosive hereditary qualities, which alludes to the investigation of arrangement of insulin, Frederick Sanger and his associates individual qualities and their parts in legacy, genomics focuses assumed a vital part in the advancement of DNA sequencing on the aggregate portrayal and evaluation of the entirety of a life strategies that empowered the foundation of thorough genome form's qualities, their interrelations and effect on the creature. sequencing projects. In 1975, he and Alan Coulson distributed a Qualities may coordinate the creation of proteins with the help sequencing methodology utilizing DNA polymerase with of chemicals and courier atoms. Thusly, proteins make up body radiolabelled nucleotides that he called the Plus and Minus designs, for example, organs and tissues just as control synthetic strategy. This elaborate two firmly related strategies that created responses and convey signals between cells. -

DNA Sequencing with Thermus Aquaticus DNA Polymerase

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 85, pp. 9436-9440, December 1988 Biochemistry DNA sequencing with Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase and direct sequencing of polymerase chain reaction-amplified DNA (thermophilic DNA polymerase/chain-termination/processivity/automation) MICHAEL A. INNIS*, KENNETH B. MYAMBO, DAVID H. GELFAND, AND MARY ANN D. BROW Department of Microbial Genetics, Cetus Corporation, 1400 Fifty-Third Street, Emeryville, CA 94608 Communicated by Hamilton 0. Smith, September 8, 1988 (receivedfor review August 15, 1988) ABSTRACT The highly thermostable DNA polymerase properties of Taq DNA polymerase that pertain to its advan- from Thermus aquaticus (Taq) is ideal for both manual and tages for DNA sequencing and its fidelity in PCR. automated DNA sequencing because it is fast, highly proces- sive, has little or no 3'-exonuclease activity, and is active over a broad range of temperatures. Sequencing protocols are MATERIALS presented that produce readable extension products >1000 Enzymes. Polynucleotide kinase from T4-infected Esche- bases having uniform band intensities. A combination of high richia coli cells was purchased from Pharmacia. Taq DNA reaction temperatures and the base analog 7-deaza-2'- polymerase, a single subunit enzyme with relative molecular deoxyguanosine was used to sequence through G+C-rich DNA mass of 94 kDa (specific activity, 200,000 units/mg; 1 unit and to resolve gel compressions. We modified the polymerase corresponds to 10 nmol of product synthesized in 30 min with chain reaction (PCR) conditions for direct DNA sequencing of activated salmon sperm DNA), was purified from Thermus asymmetric PCR products without intermediate purification aquaticus, strain YT-1 (ATCC no. -

Sanger Sequencing – a Hands-On Simulation Background And

Sanger sequencing – a hands-on simulation Background and Guidelines for Instructor Jared Young Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Jared Young, Mills College 5000 MacArthur Blvd, Oakland, CA 94613 Contact: [email protected] Synopsis This hands-on simulation teaches the Sanger (dideoxy) method of DNA sequencing. In the process of carrying out the exercise, students also confront DNA synthesis, especially as it relates to chemical structure, and the stochastic nature of biological processes. The exercise is designed for an introductory undergraduate genetics course for biology majors. The exercise can be completed in around 90-minutes, which can be broken up into a 50-minute period for the simulation and a follow-up 50-minute (or less) period for discussion. This follow-up could also take place in a Teaching Assistant (TA) led section. The exercise involves interactions between student pairs and the entire class. There is an accompanying student handout with prompts that should be invoked where indicated in these instructions. Introduction Sanger sequencing is an important technique: it revolutionized the field of Genetics and is still in wide use today. Sanger sequencing is a powerful pedagogical tool well-suited for inducing multiple “aha” moments: in achieving a deep understanding of the technique, students gain a better understanding of DNA and nucleotide structure, DNA synthesis, the stochastic nature of biological processes, the utility of visible chemical modifications (in this case, fluorescent dyes), gel electrophoresis, and the connection between a physical molecule and the information it contains. Sanger sequencing is beautiful: a truly elegant method that can bring a deep sense of satisfaction when it is fully understood. -

Genome Mapping and Genomics in Animals Volume 1

Genome Mapping and Genomics in Animals Volume 1 Series Editor: Chittaranjan Kole Wayne Hunter, Chittaranjan Kole (Editors) Genome Mapping and Genomics in Arthropods With 25 Illustrations, 3 in Color 123 Way n e Hu n t e r Chittaranjan Kole USDA, ARS, United States Department of Genetics & Biochemistry Horticultural Research Laboratory Clemson University 2001 South Rock Road Clemson, SC 29634 Fort Pierce, FL 34945 USA USA e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] ISBN 978-3-540-73832-9 e-ISBN 978-3-540-73833-6 DOI 10.1007/978-3-540-73833-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2007934674 © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2008 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broad- casting, reproduction on microfilm or in any other way, and storage in data banks. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the German Copyright Law of September 9, 1965, in its current version, and permissions for use must always be obtained from Springer. Violations are liable for prosecution under the German Copyright Law. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. Cover design: WMXDesign GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany Printed on acid-free paper 987654321 springer.com Preface to the Series The deciphering of the sequence of a gene for the first time, the gene for bacterio- phage MS2 coat protein to be specific, by Walter Fiers and his coworkers in 1972 marked the beginning of a new era in genetics, popularly known as the genomics era. -

12.2% 122000 135M Top 1% 154 4800

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE We are IntechOpen, provided by IntechOpen the world’s leading publisher of Open Access books Built by scientists, for scientists 4,800 122,000 135M Open access books available International authors and editors Downloads Our authors are among the 154 TOP 1% 12.2% Countries delivered to most cited scientists Contributors from top 500 universities Selection of our books indexed in the Book Citation Index in Web of Science™ Core Collection (BKCI) Interested in publishing with us? Contact [email protected] Numbers displayed above are based on latest data collected. For more information visit www.intechopen.com 1 DNA Representation Bharti Rajendra Kumar B.T. Kumaon Institute of Technology, Dwarahat,Almora, Uttarakhand, India 1. Introduction The term DNA sequencing refers to methods for determining the order of the nucleotides bases adenine,guanine,cytosine and thymine in a molecule of DNA. The first DNA sequence were obtained by academic researchers,using laboratories methods based on 2- dimensional chromatography in the early 1970s. By the development of dye based sequencing method with automated analysis,DNA sequencing has become easier and faster. The knowledge of DNA sequences of genes and other parts of the genome of organisms has become indispensable for basic research studying biological processes, as well as in applied fields such as diagnostic or forensic research. DNA is the information store that ultimately dictates the structure of every gene product, delineates every part of the organisms. The order of the bases along DNA contains the complete set of instructions that make up the genetic inheritance. -

Clark, Kyle.Pdf

SEQUENCING FIELD ISOLATES OF ILTV by Kyle Clark A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science in Animal Science with Distinction. Spring 2010 Copyright 2010 Kyle Clark All Rights Reserved Sequencing Field Isolates of ILTV by Kyle Clark Approved: ________________________________________________ Calvin Keeler, Ph.D. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: ________________________________________________ Carl Schmidt, Ph.D. Committee member from the Department of Animal and Food Sciences Approved:_________________________________________________ Nicole Donofrio, Ph.D. Committee member from the Board of Senior Thesis Readers Approved:__________________________________________________ Ismat Shah, Ph.D. Chair of the University Committee on Student and Faculty Honors ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Bruce Kingham for his support and sequencing assistance. I would also like to thank Cynthea Boettger for her continued assistance and instruction throughout my research. Finally, I wish to thank the University of Delaware Undergraduate Research office for their grant to further support my research. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ......................................................................................................... vi LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................... vii ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................... -

Human Genetics 1990–2009

Portfolio Review Human Genetics 1990–2009 June 2010 Acknowledgements The Wellcome Trust would like to thank the many people who generously gave up their time to participate in this review. The project was led by Liz Allen, Michael Dunn and Claire Vaughan. Key input and support was provided by Dave Carr, Kevin Dolby, Audrey Duncanson, Katherine Littler, Suzi Morris, Annie Sanderson and Jo Scott (landscaping analysis), and Lois Reynolds and Tilli Tansey (Wellcome Trust Expert Group). We also would like to thank David Lynn for his ongoing support to the review. The views expressed in this report are those of the Wellcome Trust project team – drawing on the evidence compiled during the review. We are indebted to the independent Expert Group, who were pivotal in providing the assessments of the Wellcome Trust’s role in supporting human genetics and have informed ‘our’ speculations for the future. Finally, we would like to thank Professor Francis Collins, who provided valuable input to the development of the timelines. The Wellcome Trust is a charity registered in England and Wales, no. 210183. Contents Acknowledgements 2 Overview and key findings 4 Landmarks in human genetics 6 1. Introduction and background 8 2. Human genetics research: the global research landscape 9 2.1 Human genetics publication output: 1989–2008 10 3. Looking back: the Wellcome Trust and human genetics 14 3.1 Building research capacity and infrastructure 14 3.1.1 Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute (WTSI) 15 3.1.2 Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics 15 3.1.3 Collaborations, consortia and partnerships 16 3.1.4 Research resources and data 16 3.2 Advancing knowledge and making discoveries 17 3.3 Advancing knowledge and making discoveries: within the field of human genetics 18 3.4 Advancing knowledge and making discoveries: beyond the field of human genetics – ‘ripple’ effects 19 Case studies 22 4. -

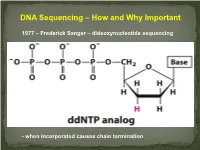

DNA Sequencing – How and Why Important

DNA Sequencing – How and Why Important 1977 – Frederick Sanger – dideoxynucleotide sequencing - when incorporated causes chain termination Original Sanger Sequencing Automated Sanger Sequencing Human Genome Project 1990 – funded as 15 year project to determine the nucleotide sequence of the entire human genome 2000 – Rough draft made available 2003 – The project was completed after final editing. Cost: $3 Billion - Identified approximately 23,000 protein coding genes - Fewer than 7 % of proteins are vertebrate specific - Complete data stored on multiple internet sites with tools for visualizing and searching UNDER currents BY KATHARINE MILLER IS CLINICAL GENOMICS TESTING WORTH IT? Cost-efectiveness studies yield answers to the complex question of whether clinical genomics testing has value. hole-genome testing has now variant and the possible benefts of test- to the right patient at the right time. reached the long-anticipated ing—are uncertain. Sequencing also Cost-efectiveness analyses are revealing W “$1,000 genome” level; and provides information about many difer- valuable benefts for certain patients, in more targeted genetic panels cost even ent genes, and each variant will have a the areas of rare pediatric disease, cancer, less. But the costs associated with diferent cost-beneft ratio. “You can’t do and pharmacogenomics. But the jury genomic testing don’t end with sequenc- a holistic view of the full beneft of these is still out as to whether whole exome ing. Additional expenditures—for follow- tests,” says Eman Biltaji, PhD, gradu- or whole genome sequencing (WES or up testing or treatments—may far exceed ate research assistant at the University of WGS) for healthy patients is worth it. -

Minds-On 4-Dna-Sequencing.Pdf

DNA BARCODING ACTION PROJECT Fish Market Survey BIOTECHNOLOGY MINDS-ON 4: DNA Sequencing Suggested Timing: 30 minutes In this hands-on activity, students will create a paper-based model of the process of DNA sequencing using the method established by Frederick Sanger in 1977 to understand how DNA is sequenced for procedures such as DNA barcoding. Prior Knowledge and Skills Success Criteria For each group of 4 students Understanding of basic mechanics of DNA replication Quality responses are BLM M5: DNA Sequencing (i.e., strand separation, annealing of primer, extension of provided during group 1 copy of DNA Sequencing – G (Guanine) DNA strand using DNA polymerase and termination) discussions 1 copy of DNA Sequencing – C (Cytosine) Understanding of complementary base pairing (C-G, A-T) Sequences correctly 1 copy of DNA Sequencing – T (Thymine) match base pair Familiarity with process of gel electrophoresis (migration 1 copy of DNA Sequencing – A (Adenine) template strand and of DNA fragments in a gel exposed to an electrical complementary 1 copy of DNA Sequencing – Group current) strand Consolidation For each group of 4 students Did you know? 4 pairs of scissors 1 green highlighter pen or marker Frederick Sanger won his second Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1 stapler 1 roll transparent tape 1980, sharing it with Walter Gilbert, for their contributions 1 pink highlighter pen or marker concerning the determination of base sequences in nucleic 1 yellow highlighter pen or marker acids, and Paul Berg for his work on recombinant DNA. 1 blue highlighter pen or marker 1. Explain to the students that they will be determining the base sequence of a piece of DNA by modelling the process of DNA sequencing through the chain termination method developed by Fred Sanger in 1977. -

Pharmacogenomics: the Right Drug to the Right Person

Elmer Press Review J Clin Med Res • 2009;1(4):191-194 Pharmacogenomics: The Right Drug to the Right Person Aneesh T Pa, b, Sonal Sekhar Ma, Asha Josea, Lekshmi Chandrana, Subin Mary Zachariaha is a complex trait that is influenced by many different genes. Abstract Without knowing all of the genes involved in drug response, scientists have found it difficult to develop genetic tests that Pharmacogenomics is the branch of pharmacology which could predict a person’s response to a particular drug [1]. deals with the influence of genetic variation on drug response in Once scientists discovered that people’s genes show small patients by correlating gene expression or single-nucleotide poly- variations (or changes) in their nucleotide (DNA base) con- morphisms with a drug’s efficacy or toxicity. It aims to develop tent, all of that changed: genetic testing for predicting drug rational means to optimize drug therapy, with respect to the pa- response is now possible. Pharmacogenomics combines tra- tient’s genotype, to ensure maximum efficacy with minimal ad- ditional pharmaceutical sciences such as biochemistry with verse effects. Such approaches promise the advent of ‘personalized medicine’, in which drugs and drug combinations are optimized for annotated knowledge of genes, proteins, and single nucle- each individual’s unique genetic makeup. Pharmacogenomics is the otide polymorphisms. The most common variations in the whole genome application of pharmacogenetics, which examines human genome are called single nucleotide polymorphisms the single gene interactions with drugs. (SNPs). There is estimated to be approximately 11 million SNPs in the human population, with an average of one every 1,300 base pairs. -

Drug Targets of the Heartworm, Dirofilaria Immitis

Drug Targets of the Heartworm, Dirofilaria immitis Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des Würde eines Doktors der Philosophie vorgelegt der Philosophisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Basel von Christelle Godel aus La Sagne (NE) und Domdidier (FR) Schweiz Avenches, 2012 Genehmigt von der Philosophisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät auf Antrag von Prof. Dr. Jürg Utzinger Prof. Dr. Pascal Mäser P.D. Dr. Ronald Kaminsky Prof. Dr. Georg von Samson-Himmelstjerna Basel, den 26th of June 2012 Prof. Dr. M. Spiess Dekan To my husband and my daughter With all my love. Table of Content P a g e | 2 Table of Content Table of Content P a g e | 3 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................... 5 Summary ............................................................................................................................... 8 Introduction ..........................................................................................................................11 Dirofilaria immitis ..............................................................................................................12 Phylogeny and morphology ...........................................................................................12 Repartition and ecology .................................................................................................14 Life cycle .......................................................................................................................16 -

Generations of Sequencing Technologies: from First to Next

nd M y a ed g ic lo i o n i e B Kchouk et al., Biol Med (Aligarh) 2017, 9:3 DOI: 10.4172/0974-8369.1000395 ISSN: 0974-8369 Biology and Medicine Review Article Open Access Generations of Sequencing Technologies: From First to Next Generation Mehdi Kchouk1,3*, Jean-François Gibrat2 and Mourad Elloumi3 1Faculty of Sciences of Tunis (FST), Tunis El-Manar University, Tunisia 2Research Unit Applied Mathematics and Computer Science, from Genomes to the Environment' (MaIAGE), Jouy en Josas, France 3Laboratory of Technologies of Information and Communication and Electrical Engineering, National Superior School of Engineers of Tunis, University of Tunis, Tunisia *Corresponding author: Mehdi Kchouk, Faculty of Sciences of Tunis (FST), Tunis El-Manar University, Tunisia, Tel: +216 71 872 253; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: January 31, 2017; Accepted date: February 27, 2017; Published date: March 06, 2017 Copyright: © 2017 Kchouk M, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract DNA sequencing process utilizes biochemical methods in order to determine the correct order of nucleotide bases in a DNA macromolecule using sequencing machines. Ten years ago, sequencing was based on a single type of sequencing that is Sanger sequencing. In 2005, Next Generation Sequencing Technologies emerged and changed the view of the analysis and understanding of living beings. Over the last decade, considerable progress has been made on new sequencing machines. In this paper, we present a non-exhaustive overview of the sequencing technologies by beginning with the first methods history used by the commonly used NGS platforms until today.