Most Insect Colonisers of an Introduced Fig Tree in Cyprus Come

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BÖCEKLERİN SINIFLANDIRILMASI (Takım Düzeyinde)

BÖCEKLERİN SINIFLANDIRILMASI (TAKIM DÜZEYİNDE) GÖKHAN AYDIN 2016 Editör : Gökhan AYDIN Dizgi : Ziya ÖNCÜ ISBN : 978-605-87432-3-6 Böceklerin Sınıflandırılması isimli eğitim amaçlı hazırlanan bilgisayar programı için lütfen aşağıda verilen linki tıklayarak programı ücretsiz olarak bilgisayarınıza yükleyin. http://atabeymyo.sdu.edu.tr/assets/uploads/sites/76/files/siniflama-05102016.exe Eğitim Amaçlı Bilgisayar Programı ISBN: 978-605-87432-2-9 İçindekiler İçindekiler i Önsöz vi 1. Protura - Coneheads 1 1.1 Özellikleri 1 1.2 Ekonomik Önemi 2 1.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 2 2. Collembola - Springtails 3 2.1 Özellikleri 3 2.2 Ekonomik Önemi 4 2.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 4 3. Thysanura - Silverfish 6 3.1 Özellikleri 6 3.2 Ekonomik Önemi 7 3.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 7 4. Microcoryphia - Bristletails 8 4.1 Özellikleri 8 4.2 Ekonomik Önemi 9 5. Diplura 10 5.1 Özellikleri 10 5.2 Ekonomik Önemi 10 5.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 11 6. Plocoptera – Stoneflies 12 6.1 Özellikleri 12 6.2 Ekonomik Önemi 12 6.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 13 7. Embioptera - webspinners 14 7.1 Özellikleri 15 7.2 Ekonomik Önemi 15 7.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 15 8. Orthoptera–Grasshoppers, Crickets 16 8.1 Özellikleri 16 8.2 Ekonomik Önemi 16 8.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 17 i 9. Phasmida - Walkingsticks 20 9.1 Özellikleri 20 9.2 Ekonomik Önemi 21 9.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 21 10. Dermaptera - Earwigs 23 10.1 Özellikleri 23 10.2 Ekonomik Önemi 24 10.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 24 11. Zoraptera 25 11.1 Özellikleri 25 11.2 Ekonomik Önemi 25 11.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 26 12. -

Ficus Microcarpa Chinese Banyan Moraceae

Ficus microcarpa Chinese banyan Moraceae Forest Starr, Kim Starr, and Lloyd Loope United States Geological Survey--Biological Resources Division Haleakala Field Station, Maui, Hawai'i January, 2003 OVERVIEW Ficus microcarpa is a popular ornamental tree grown widely in many tropical regions of the world. The pollinator wasp has been introduced to a number of places where the tree is cultivated, including Hawai'i, allowing this species to spread beyond initial plantings. F. microcarpa is a notorious invader in Hawai'i, Florida, Bermuda, and from Central to South America. Tiny seeds within small sized fruit are ingested by many fruit eating animals, such as birds. Seeds are capable of germinating and growing almost anywhere they land, even in cracks in concrete or in the crotch of other trees. The small seedling begins to grow on its host, sending down aerial roots, and eventually strangling and replacing the host tree or structure. In Hawai'i, most of the main islands are infested with F. microcarpa. Typically, this species invades disturbed urban sites to degraded secondary forests in areas nearby initial plantings. It has recently been observed growing on native wiliwili (Erythrina sandwicense) in lowland dry forests of Maui. On the main islands of Hawai'i, rapid containment once inside natural area boundaries may be the only feasible action, given the widespread distribution. On Midway Atoll, the wasp was introduced later than on the main islands and, as a result, F. microcarpa has only recently begun to spread there. With limited distribution, control here seems more feasible than on the main islands. To decrease the potential for this species to spread, it should not be introduced to new areas and could be removed in natural areas where it is limited in distribution. -

Aerial Roots of Ficus Microcarpa Phelloderm

"Chinese Banyan grows Aerial roots of ‘rapidly with but little care, its Ficus microcarpa foliage is of a glossy green Mathew Pryor and Li Wei colour, and it soon affords an agreeable shade from the fierce rays of the sun, which renders it particularly valuable in a place like Hong-kong’." Robert Fortune, (1852). A Journey to the Tea Countries of China Section of flexible aerial root of Ficus microcarpa This article reports on a study to The distribution and growth of aerial since the beginning of the colonial investigate the nature of aerial roots in roots was observed to be highly variable, period,2 and was used almost exclusively Chinese banyan trees, Ficus microcarpa, but there was a clear link between for this purpose until the 1870s.3 The and the common belief that their growth and high levels of atmospheric botanist Robert Fortune noted, as early presence and growth is associated with humidity. The anatomical structure of as 1852,4 that the Banyan grew ‘rapidly wet atmospheric conditions. the aerial roots suggests that while with but little care, its foliage is of a aerial roots could absorb water under glossy green colour, and it soon affords First, the form and distribution of free- certain conditions, their growth was an agreeable shade from the fierce rays hanging aerial roots on eight selected generated from water drawn from of the sun, which renders it particularly Ficus microcarpa trees growing in a terrestrial roots via trunk and branches, valuable in a place like Hong-kong’. public space in Hong Kong, were mapped and that the association with humid Even the Hongkong Governor, in 1881, on their form and distribution. -

Macaques ( Macaca Leonina ): Impact on Their Seed Dispersal Effectiveness and Ecological Contribution in a Tropical Rainforest at Khao Yai National Park, Thailand

Faculté des Sciences Département de Biologie, Ecologie et Environnement Unité de Biologie du Comportement, Ethologie et Psychologie Animale Feeding and ranging behavior of northern pigtailed macaques ( Macaca leonina ): impact on their seed dispersal effectiveness and ecological contribution in a tropical rainforest at Khao Yai National Park, Thailand ~ ~ ~ Régime alimentaire et déplacements des macaques à queue de cochon ( Macaca leonina ) : impact sur leur efficacité dans la dispersion des graines et sur leur contribution écologique dans une forêt tropicale du parc national de Khao Yai, Thaïlande Année académique 2011-2012 Dissertation présentée par Aurélie Albert en vue de l’obtention du grade de Docteur en Sciences Faculté des Sciences Département de Biologie, Ecologie et Environnement Unité de Biologie du Comportement, Ethologie et Psychologie Animale Feeding and ranging behavior of northern pigtailed macaques ( Macaca leonina ): impact on their seed dispersal effectiveness and ecological contribution in a tropical rainforest at Khao Yai National Park, Thailand ~ ~ ~ Régime alimentaire et déplacements des macaques à queue de cochon ( Macaca leonina ) : impact sur leur efficacité dans la dispersion des graines et sur leur contribution écologique dans une forêt tropicale du parc national de Khao Yai, Thaïlande Année académique 2011-2012 Dissertation présentée par Aurélie Albert en vue de l’obtention du grade de Docteur en Sciences Promotrice : Marie-Claude Huynen (ULg, Belgique) Comité de thèse : Tommaso Savini (KMUTT, Thaïlande) Alain Hambuckers (ULg, Belgique) Pascal Poncin (ULg, Belgique) Président du jury : Jean-Marie Bouquegneau (ULg, Belgique) Membres du jury : Pierre-Michel Forget (MNHN, France) Régine Vercauteren Drubbel (ULB, Belgique) Roseline C. Beudels-Jamar (IRSN, Belgique) Copyright © 2012, Aurélie Albert Toute reproduction du présent document, par quelque procédé que ce soit, ne peut être réalisée qu’avec l’autorisation de l’auteur et du/des promoteur(s). -

Entry & Buffer Landscape Plans

PLANT MATERIAL SCHEDULE PLANTI NGT DETAl LS ;;;;;.;;;;..;;;.....;....,;;LOCATION.......... ..,.;...,.;.,=......,;;,;,,,;;...;,;,/ KEY MAP___________________ i'LT.S. - V') a.. a..~ II f~I !~~...~l"""'''"'i. M Code Quantity Botanical Common Cont/Cal Size Native Remarks ,,,.,;<_..;@.~·/ s w ...J _.. ~~ . 1/ I ,. LLl N CSlO 26 CASSIA SURATTENSIS CASSIA GLAUCA 10' HTX8' SPR . ...J M ~1/ 1 I- IC 55 ILEX CASSI NE OAHOON HOLLY · 14' OAH NATIVE 4' c.t. ~ _J M TRIM ONLY THOSE FRONDS WHICH HANG COR 45 CORDIA SEBESTENA ORANGE GEIGER TREE 10'HTX5'SPR hK 0 M BELOW LEVEL OF TREE HEART. ~ PE12 31 PINUS ELLIOTT! 'DENSA' SLASH PINE 12', 14', 16' o.a. NATIVE staggered hts <( SABALS: 'HURRICANE cur FRONDS PRIOR TO DELIVERY. w 0 QV14 103 QUERCUS VIRGINIANA SOUTHERN LIVE DAI( 14' HTX 7' SPR NATIVE :C> 0 0 ROYALS: SECURE FRONDS PRIOR TO SHIPPING TO > a.. QV20 10 QUERCUS VIRGINIANA SOUTHERN LIVE OAK 20'HT 0:: - c::: 0 - NATIVE PROTECT BUD. w >- V') 0 "'-I" c::: MG 28 MAGNOLIA GRANDIFLORA SOUTHERN MAGNOLIA 16'HT NATIVE NO SCARRED TRUNKS WILL BE ACCEPTED. (/) CV 4 CALLISTEMON VIMINALIS WEEPING BOTTLE BRUSH 10'HTX5'SPR 4' ct ~ SECURE WITH THREE WOOD BATTENS HELD WITH w 1-w U LLl 0 0:: I- _J Code Quantity Botanical Common Cont/Cal Size Native Remarks METAL STRAPS/3-2 X 4" BRACES. Q_ z I- V"l LL.. NO NAILS IN TRUNK; PROTECT TRUNK WITH BURLAP. SP 143 SABAL PALMETTO CABBAGE PALMETTO 14' · 18' OAH NATIVE V"l :::, staggered ROOT BALL TO BE 10% ABOVE FIN. GRADE :::) <:( VM 13 VEITCH IA MONTGOMERYANA MONTGOMERY PALM 16'CT V"l - 3" DEEP/3' DIA. -

Ficus Plants for Hawai'i Landscapes

Ornamentals and Flowers May 2007 OF-34 Ficus Plants for Hawai‘i Landscapes Melvin Wong Department of Tropical Plant and Soil Sciences icus, the fig genus, is part of the family Moraceae. Many ornamental Ficus species exist, and probably FJackfruit, breadfruit, cecropia, and mulberry also the most colorful one is Ficus elastica ‘Schrijveriana’ belong to this family. The objective of this publication (Fig. 8). Other Ficus elastica cultivars are ‘Abidjan’ (Fig. is to list the common fig plants used in landscaping and 9), ‘Decora’ (Fig. 10), ‘Asahi’ (Fig. 11), and ‘Gold’ (Fig. identify some of the species found in botanical gardens 12). Other banyan trees are Ficus lacor (pakur tree), in Hawai‘i. which can be seen at Foster Garden, O‘ahu, Ficus When we think of ficus (banyan) trees, we often think benjamina ‘Comosa’ (comosa benjamina, Fig. 13), of large trees with aerial roots. This is certainly accurate which can be seen on the UH Mänoa campus, Ficus for Ficus benghalensis (Indian banyan), Ficus micro neriifolia ‘Nemoralis’ (Fig. 14), which can be seen at carpa (Chinese banyan), and many others. Ficus the UH Lyon Arboretum, and Ficus rubiginosa (rusty benghalensis (Indian banyan, Fig. 1) are the large ban fig, Fig. 15). yans located in the center of Thomas Square in Hono In tropical rain forests, many birds and other animals lulu; the species is also featured in Disneyland (although feed on the fruits of different Ficus species. In Hawaii the tree there is artificial). Ficus microcarpa (Chinese this can be a negative feature, because large numbers of banyan, Fig. -

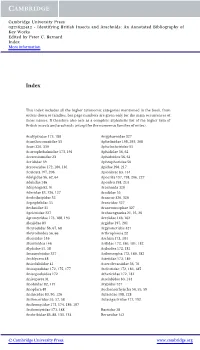

Identifying British Insects and Arachnids: an Annotated Bibliography of Key Works Edited by Peter C

Cambridge University Press 0521632412 - Identifying British Insects and Arachnids: An Annotated Bibliography of Key Works Edited by Peter C. Barnard Index More information Index This index includes all the higher taxonomic categories mentioned in the book, from orders down to families, but page numbers are given only for the main occurrences of those names. It therefore also acts as a complete alphabetic list of the higher taxa of British insects and arachnids (except for the numerous families of mites). Acalyptratae 173, 188 Anyphaenidae 327 Acanthosomatidae 55 Aphelinidae 198, 293, 308 Acari 320, 330 Aphelocheiridae 55 Acartophthalmidae 173, 191 Aphididae 56, 62 Acerentomidae 23 Aphidoidea 56, 61 Acrididae 39 Aphrophoridae 56 Acroceridae 172, 180, 181 Apidae 198, 217 Aculeata 197, 206 Apioninae 83, 134 Adelgidae 56, 62, 64 Apocrita 197, 198, 206, 227 Adelidae 146 Apoidea 198, 214 Adephaga 82, 91 Arachnida 320 Aderidae 83, 126, 127 Aradidae 55 Aeolothripidae 52 Araneae 320, 326 Aepophilidae 55 Araneidae 327 Aeshnidae 31 Araneomorphae 327 Agelenidae 327 Archaeognatha 21, 25, 26 Agromyzidae 173, 188, 193 Arctiidae 146, 162 Alexiidae 83 Argidae 197, 201 Aleyrodidae 56, 67, 68 Argyronetidae 327 Aleyrodoidea 56, 66 Arthropleona 22 Alucitidae 146 Aschiza 173, 184 Alucitoidea 146 Asilidae 172, 180, 181, 182 Alydidae 55, 58 Asiloidea 172, 181 Amaurobiidae 327 Asilomorpha 172, 180, 182 Amblycera 48 Asteiidae 173, 189 Anisolabiidae 41 Asterolecaniidae 56, 70 Anisopodidae 172, 175, 177 Atelestidae 172, 183, 185 Anisopodoidea 172 Athericidae 172, 181 Anisoptera 31 Attelabidae 83, 134 Anobiidae 82, 119 Atypidae 327 Anoplura 48 Auchenorrhyncha 54, 55, 59 Anthicidae 83, 90, 126 Aulacidae 198, 228 Anthocoridae 55, 57, 58 Aulacigastridae 173, 192 Anthomyiidae 173, 174, 186, 187 Anthomyzidae 173, 188 Baetidae 28 Anthribidae 83, 88, 133, 134 Beraeidae 142 © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521632412 - Identifying British Insects and Arachnids: An Annotated Bibliography of Key Works Edited by Peter C. -

Hemiptera: Psylloidea) on Ficus Carica (Moraceae

J. Entomol. Res. Soc., 20(3): 39-52, 2018 Research Article Print ISSN:1302-0250 Online ISSN:2651-3579 Taxonomy and Biology of Pauropsylla buxtoni comb. nov. (Hemiptera: Psylloidea) on Ficus carica (Moraceae) Yacoub BATTA1* Daniel BURCKHARDT2 1Department of Plant Production and Protection, Faculty of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine, An-Najah National University, Nablus, West Bank, THE PALESTINIAN TERRITORIES 2Naturhistorisches Museum, Augustinergasse 2, 4001 Basel, SWITZERLAND e-mails: *[email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT A detailed morphological study of adult and immature Trioza buxtoni Laing, 1924 (Hemiptera: Psylloidea: Triozidae) shows that the species belongs to the tropical and subtropical genus Pauropsylla Rübsaamen, 1899 to which it is transferred. The adult of Pauropsylla buxtoni (Laing, 1924) comb. nov. is redescribed and the previously unknown immatures are described. Illustrations are provided for both adults and immatures. Immatures of P. buxtoni infest leaves of Ficus carica and induce conspicuous galls. The species is a pest on cultivated figs in the Palestinian Territories. Four successive phases in the formation and development of the galls can be recognised in which the five immature instars ofP. buxtoni develop. The gall size increased significantly when the instar length increased and there were significant differences in the susceptibility of fig cultivars to psyllid infestation. The life cycle ofP. buxtoni is univoltine with no significant differences between cultivars. Key words: Triozidae, description, immatures, life cycle, cultivar, susceptibility, gall development. Batta, Y., Burckhardt, D. (2018). Taxonomy and biology of Pauropsylla buxtoni comb. nov. (Hemiptera: Psylloidea) on Ficus carica (Moraceae). Journal of the Entomological Research Society, 20(3), 39-52. -

Appendix 4.3 Biological Resources

Appendix 4.3 Biological Resources 4.3.1 Preliminary Tree Survey of APM Alignment (TBD) 4.3.2 Preliminary Tree Survey of Potential Support Facility Sites (TBD) 4.3.3 Tree Inventory Inglewood Transit Connector Project Tree Inventory Prepared for: Meridian Consultants 920 Hampshire Road, Suite A5 Westlake Village, CA 91361 805.367.5720 www.meridianconsultants.com Prepared by: Pax Environmental, Inc. Certified DBE/DVBE/SBE 226 West Ojai Ave., Ste. 101, #157 Ojai, CA 93023 805.633.9218 www.paxenviro.com December 10, 2018 Inglewood Transit Connector Project Section Page Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Project Location ............................................................................................. 1 1.2 Project Description and Background .............................................................. 1 1.3 Regulatory Setting ......................................................................................... 1 Survey Methodology ............................................................................................... 2 Results ..................................................................................................................... 3 References ............................................................................................................... 4 Tables Page 1 Tree species observed in the project alignment .................................................. 3 ATTACHMENTS APPENDIX 1 TREE POINT LOCATION MAP -

The Psyllid Macrohomotoma Gladiata Kuwayama, 1908 (Hemiptera: Psylloidea: Homotomidae): a Ficus Pest Recently Introduced in the EPPO Region

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OAR@UM Bulletin OEPP/EPPO Bulletin (2012) 42 (1), 161–164 ISSN 0250–8052. DOI: 10.1111/epp.2544 The psyllid Macrohomotoma gladiata Kuwayama, 1908 (Hemiptera: Psylloidea: Homotomidae): a Ficus pest recently introduced in the EPPO region D. Mifsud1 and F. Porcelli2 1Department of Biology, Junior College, University of Malta, Msida MSD 1252 (Malta); e-mail: [email protected] 2DiBCA Sez. Entomologia e Zoologia, Universita` degli Studi di Bari Aldo Moro, Bari (Italy) The psyllid Macrohomotoma gladiata, is a new insect pest of Ficus originating from Asia which has recently been found in Spain (Alicante) on urban Ficus microcarpa trees. This species may be of phy- tosanitary concern because of its leaf wrapping habits, wax secretion and honeydew excretion that may lead to direct and secondary twig damage. Although more studies are needed on the biology of M. gladiata, it is suspected that it might behave in the Euro-Mediterranean as an invasive alien species. The predation by Anthocoris sp. (nemoralis?) needs to be investigated in order to assess its effective- ness as a natural biological control agent. This is the first report of M. gladiata from the EPPO region. The trees had been planted there several years before (observa- Introduction tions by local personnel) and similar damage on the twigs of the The Oriental region, and its Indo-Burma and Sundaland biodiver- same plants had been noted during the previous year (2010). All sity hotspots (Mittermeier et al., 2011), is one of the major areas photos of living material were taken on site. -

ARTHROPODA Subphylum Hexapoda Protura, Springtails, Diplura, and Insects

NINE Phylum ARTHROPODA SUBPHYLUM HEXAPODA Protura, springtails, Diplura, and insects ROD P. MACFARLANE, PETER A. MADDISON, IAN G. ANDREW, JOCELYN A. BERRY, PETER M. JOHNS, ROBERT J. B. HOARE, MARIE-CLAUDE LARIVIÈRE, PENELOPE GREENSLADE, ROSA C. HENDERSON, COURTenaY N. SMITHERS, RicarDO L. PALMA, JOHN B. WARD, ROBERT L. C. PILGRIM, DaVID R. TOWNS, IAN McLELLAN, DAVID A. J. TEULON, TERRY R. HITCHINGS, VICTOR F. EASTOP, NICHOLAS A. MARTIN, MURRAY J. FLETCHER, MARLON A. W. STUFKENS, PAMELA J. DALE, Daniel BURCKHARDT, THOMAS R. BUCKLEY, STEVEN A. TREWICK defining feature of the Hexapoda, as the name suggests, is six legs. Also, the body comprises a head, thorax, and abdomen. The number A of abdominal segments varies, however; there are only six in the Collembola (springtails), 9–12 in the Protura, and 10 in the Diplura, whereas in all other hexapods there are strictly 11. Insects are now regarded as comprising only those hexapods with 11 abdominal segments. Whereas crustaceans are the dominant group of arthropods in the sea, hexapods prevail on land, in numbers and biomass. Altogether, the Hexapoda constitutes the most diverse group of animals – the estimated number of described species worldwide is just over 900,000, with the beetles (order Coleoptera) comprising more than a third of these. Today, the Hexapoda is considered to contain four classes – the Insecta, and the Protura, Collembola, and Diplura. The latter three classes were formerly allied with the insect orders Archaeognatha (jumping bristletails) and Thysanura (silverfish) as the insect subclass Apterygota (‘wingless’). The Apterygota is now regarded as an artificial assemblage (Bitsch & Bitsch 2000). -

Date Palm Tamar Matzu’I תמר מצוי :Hebrew Name Scientific Name: Phoenix Dactylifera نخيل :Arabic Name Family: Arecaceae (Palmae)

Signs 10-18 Common name: Date Palm tamar matzu’i תמר מצוי :Hebrew name Scientific name: Phoenix dactylifera نخيل :Arabic name Family: Arecaceae (Palmae) “The righteous shall flourish like the palm-tree; he DatE PaLM shall grow like a cedar in Lebanon” (Psalms 92:12/13) A tall palm tree, one of the symbols of the des- dates; the color of the fruit ranges from yellow to ert. Its trunk is tall and straight, and it bears “scars” dark red. that are remnants of old leaves that have been shed The date palm grows wild throughout the Near or removed. Additional trunks may grow from the East and North Africa and, as a fruit tree, has spread base of the main trunk. At the top of the trunks are around the world. All parts of the tree are used by crowns of large, stiff pinnate leaves. The bluish-gray humans: the trunks for construction, the leaves for leaves (palm fronds) are divided into leaflets with roofing, the fruit-bearing branches for brooms, and pointed tips. the seeds for medicinal purposes. The date palm The date palm is dioecious: large inflorescences is often mentioned in the Bible as an example of a (clusters) of male and female flowers develop on multi-use plant. It is one of the seven species with separate trees. In its natural habitat, the wind which the Land of Israel is blessed, and the lulav – a pollinates female trees, but this is done manually for closed date palm frond – is one of the four species cultivated trees.