Season 2016-2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Arts Awards Monday, October 19, 2015

2015 Americans for the Arts National Arts Awards Monday, October 19, 2015 Welcome from Robert L. Lynch Performance by YoungArts Alumni President and CEO of Americans for the Arts Musical Director, Jake Goldbas Philanthropy in the Arts Award Legacy Award Joan and Irwin Jacobs Maria Arena Bell Presented by Christopher Ashley Presented by Jeff Koons Outstanding Contributions to the Arts Award Young Artist Award Herbie Hancock Lady Gaga 1 Presented by Paul Simon Presented by Klaus Biesenbach Arts Education Award Carolyn Clark Powers Alice Walton Lifetime Achievement Award Presented by Agnes Gund Sophia Loren Presented by Rob Marshall Dinner Closing Remarks Remarks by Robert L. Lynch and Abel Lopez, Chair, introduction of Carolyn Clark Powers Americans for the Arts Board of Directors and Robert L. Lynch Remarks by Carolyn Clark Powers Chair, National Arts Awards Greetings from the Board Chair and President Welcome to the 2015 National Arts Awards as Americans for the Arts celebrates its 55th year of advancing the arts and arts education throughout the nation. This year marks another milestone as it is also the 50th anniversary of President Johnson’s signing of the act that created America’s two federal cultural agencies: the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities. Americans for the Arts was there behind the scenes at the beginning and continues as the chief advocate for federal, state, and local support for the arts including the annual NEA budget. Each year with your help we make the case for the funding that fuels creativity and innovation in communities across the United States. -

American Masters 200 List Finaljan2014

Premiere Date # American Masters Program Title (Month-YY) Subject Name 1 ARTHUR MILLER: PRIVATE CONVERSATIONS On the Set of "Death of a Salesman" June-86 Arthur Miller 2 PHILIP JOHNSON: A SELF PORTRAIT June-86 Philip Johnson 3 KATHERINE ANNE PORTER: THE EYE OF MEMORY July-86 Katherine Anne Porter 4 UNKNOWN CHAPLIN (Part 1) July-86 Charlie Chaplin 5 UNKNOWN CHAPLIN (Part 2) July-86 Charlie Chaplin 6 UNKNOWN CHAPLIN (Part 3) July-86 Charlie Chaplin 7 BILLIE HOLIDAY: THE LONG NIGHT OF LADY DAY August-86 Billie Holiday 8 JAMES LEVINE: THE LIFE IN MUSIC August-86 James Levine 9 AARON COPLAND: A SELF PORTRAIT August-86 Aaron Copland 10 THOMAS EAKINS: A MOTION PORTRAIT August-86 Thomas Eakins 11 GEORGIA O'KEEFFE September-86 Georgia O'Keeffe 12 EUGENE O'NEILL: A GLORY OF GHOSTS September-86 Eugene O'Neill 13 ISAAC IN AMERICA: A JOURNEY WITH ISAAC BASHEVIS SINGER July-87 Isaac Bashevis Singer 14 DIRECTED BY WILLIAM WYLER July-87 William Wyler 15 ARTHUR RUBENSTEIN: RUBENSTEIN REMEMBERED July-87 Arthur Rubinstein 16 ALWIN NIKOLAIS AND MURRAY LOUIS: NIK AND MURRAY July-87 Alwin Nikolais/Murray Louis 17 GEORGE GERSHWIN REMEMBERED August-87 George Gershwin 18 MAURICE SENDAK: MON CHER PAPA August-87 Maurice Sendak 19 THE NEGRO ENSEMBLE COMPANY September-87 Negro Ensemble Co. 20 UNANSWERED PRAYERS: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF TRUMAN CAPOTE September-87 Truman Capote 21 THE TEN YEAR LUNCH: THE WIT AND LEGEND OF THE ALGONQUIN ROUND TABLE September-87 Algonquin Round Table 22 BUSTER KEATON: A HARD ACT TO FOLLOW (Part 1) November-87 Buster Keaton 23 BUSTER KEATON: -

Leonard Bernstein

TuneUp! TuneUSaturday, October 18th, 2008 p! New York Philharmonic Young People’s Concert® elcome to a new season of Young People’s Concerts! Throughout history, there have been special times when music flowered in specific cities—Capitals of Music—that for a while W became the center of the musical world. Much of the music we know today comes from these times and places. But how did these great flowerings of music happen? That’s what we’ll find out this year as we discover the distinctive sounds of four of these Capitals. And where better to start than right here in New York? After the Second World War, our city became a cultural capital of the world. Leonard Bernstein—who became Music Director of the New York Philharmonic 50 years ago this fall—defined music in New York in his roles as composer, conductor, and teacher. So what was it like in New York back then? Let’s find out from a child of that time—Leonard Bernstein’s BERNSTEIN’S NEW YORK daughter Jamie! THE PROGRAM: BERNSTEIN “The Great Lover” from On the Town COPLAND “Skyline” from Music for a Great City (excerpt) GERSHWIN “I Got Rhythm” from Girl Crazy BERNSTEIN “America” from West Side Story Suite No. 2 COPLAND Fanfare for the Common Man Jamie Bernstein, host BERNSTEIN On the Waterfront Symphonic Suite (excerpt) Delta David Gier, conductor SEBASTIAN CURRIER “quickchange” from Microsymph Tom Dulack, scriptwriter and director BERNSTEIN Overture to Candide 1 2 3 5 4 CAN YOU IDENTIFY EVERYTHING IN AND AROUND LEONARD BERNSTEIN’S NEW YORK STUDIO? LOOK ON THE BACK PAGE TO SEE WHETHER YOU’RE RIGHT. -

Our History 1971-2018 20 100 Contents

OUR HISTORY 1971-2018 20 100 CONTENTS 1 From the Founder 4 A Poem by Aaron Stern 6 Our Mission 6 Academy Timeline 8 Academy Programs 22 20 Years in Pictures 26 20 Years in Numbers 26 Where We’ve Worked 27 20th Anniversary Events 28 20th Anniversary Images Send correspondence to: Laura Pancoast, Development Coordinator 133 Seton Village Road Santa Fe, NM 87508 [email protected] ON THE COVER & LEFT: Academy for the Love of Learning photo © Kate Russell 20 YEARS of the Academy for the Love of Learning Copyright © 2018 Academy for the Love of Learning, Inc. 2018 has been a very special year, as it marks the 20th anniversary of FROM THE FOUNDER the Academy’s official founding in 1998. 2018 is also, poignantly and coincidentally, the 100th anniversary of Leonard Bernstein’s birth. Lenny, as I knew him, the great musician, the 20th century giant with whom, in 1986, I conceived the Academy, was one of the first people with whom I engaged in dialogue about “this thing,” as he called it, just before proposing that we call our “thing” the Academy for the Love of Learning. “Why that name?”, I asked – and he said: “because you believe that if we truly open ourselves to learning, it will liberate us and bring us home, individually and collectively. So, the name is perfect, because the acronym is ALL!” I resisted it at first, but soon came to realize that the name indeed was perfect. This and other prescient dialogues have helped us get to where we are today – a thriving, innovative organization. -

The "Stars for Freedom" Rally

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Selma-to-Montgomery National Historic Trail The "Stars for Freedom" Rally March 24,1965 The "March to Montgomery" held the promise of fulfilling the hopes of many Americans who desired to witness the reality of freedom and liberty for all citizens. It was a movement which drew many luminaries of American society, including internationally-known performers and artists. In a drenching rain, on the fourth day, March 24th, carloads and busloads of participants joined the march as U.S. Highway 80 widened to four lanes, thus allowing a greater volume of participants than the court- imposed 300-person limitation when the roadway was narrower. There were many well-known celebrities among the more than 25,000 persons camped on the 36-acre grounds of the City of St. Jude, a Catholic social services complex which included a school, hospital, and other service facilities, located within the Washington Park neighborhood. This fourth campsite, situated on a rain-soaked playing field, held a flatbed trailer that served as a stage and a host of famous participants that provided the scene for an inspirational performance enjoyed by thousands on the dampened grounds. The event was organized and coordinated by the internationally acclaimed activist and screen star Harry Belafonte, on the evening of March 24, 1965. The night "the Stars" came out in Alabama Mr. Belafonte had been an acquaintance of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. since 1956. He later raised thousands of dollars in funding support for the Freedom Riders and to bailout many protesters incarcerated during the era, including Dr. -

Fall/Winter 2002/2003

PRELUDE, FUGUE News for Friends of Leonard Bernstein RIFFS Fall/ Winter 2002 Bernstein's Mahler: A Personal View @ by Sedgwick Clark n idway through the Adagio £male of Mahler's Ninth M Symphony, the music sub sides from an almost desperate turbulence. Questioning wisps of melody wander throughout the woodwinds, accompanied by mut tering lower strings and a halting harp ostinato. Then, suddenly, the orchestra "vehemently burst[s] out" fortissimo in a final attempt at salvation. Most conductors impart a noble arch and beauty of tone to the music as it rises to its climax, which Leonard Bernstein did in his Vienna Philharmonic video recording in March 1971. But only seven months before, with the New York Philharmonic, His vision of the music is neither Nearly all of the Columbia cycle he had lunged toward the cellos comfortable nor predictable. (now on Sony Classical), taped with a growl and a violent stomp Throughout that live performance I between 1960 and 1974, and all of on the podium, and the orchestra had been struck by how much the 1980s cycle for Deutsche had responded with a ferocity I more searching and spontaneous it Grammophon, are handily gath had never heard before, or since, in was than his 1965 recording with ered in space-saving, budget-priced this work. I remember thinking, as the orchestra. Bernstein's Mahler sets. Some, but not all, of the indi Bernstein tightened the tempo was to take me by surprise in con vidual releases have survived the unmercifully, "Take it easy. Not so cert many times - though not deletion hammerschlag. -

Patuna, Genehouaiy Suppott the Opeltation Oti the Tangtewood

TANGLEWOOD MUSIC CENTER The Tanglewood Music Center is maintained by the Boston Symphony Orchestra to offer advanced training in music to young pre-professional musicians. The Orchestra underwrites the cost of operating the Music Center with generous help from donors to the Annual Fellowship Program and with the sustaining support of income from the following permanent endowment funds: Faculty Funds Chairman of the Faculty endowed by the Charles E. Culpeper Foundation Head of Keyboard Activities endowed in memory of Marian Douglas Martin by Marilyn Brachman Hoffman Master Teacher endowed by Mr. and Mrs. Edward L. Bowles Endowed Guarantor Fellowships Leonard Bernstein Fellowship Charles E. Culpeper Foundation Omar del Carlo Tanglewood Fellowship Clowes Fund Fellowship Endowed Fellowshi s in the Following Names Anonymous The Luke B. Hancock Foundation Mr. and Mrs. David B. Arnold, Jr. Harold Hodgkinson Kathleen Hall Banks C. D. Jackson Leo L. Beranek Philip and Bernice Krupp Leonard Bernstein Lucy Lowell Helene R. and Norman L. Cahners Stephen and Persis Morris Rosamond Sturgis Brooks Ruth S. Morse Stanley Chapple Albert L. and Elizabeth P. Nickerson Alfred E. Chase- Northern California Fund Nat King Cole Theodore Edson Parker Foundation Caroline Grosvenor Congdon David R. and Muriel K. Pokross Dr. Marshall N. Fulton Daphne Brooks Prout Juliet Esselborn Geier Harry and Mildred Remis Gerald Gelbloom Hannah and Raymond Schneider Armando A. Ghitalla Surdna Foundation, Inc. Fernand Gillet R. Amory Thorndike Marie Gillet Augustus Thorndike John and Susanne Grandin Other Funds Anonymous Jascha Heifetz Fund The Rothenberg/Carlyle Foundation Fund Howard/Ehrlich Fund Charles E. Merrill Trust Fund Dorothy Lewis Fund Koussevitzky Centenrial Fund Northern California Audition Fund Jason Starr Fund Asher J. -

Leonard Bernstein's MASS

27 Season 2014-2015 Thursday, April 30, at 8:00 Friday, May 1, at 8:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, May 2, at 8:00 Sunday, May 3, at 2:00 Leonard Bernstein’s MASS: A Theatre Piece for Singers, Players, and Dancers* Conducted by Yannick Nézet-Séguin Texts from the liturgy of the Roman Mass Additional texts by Stephen Schwartz and Leonard Bernstein For a list of performing and creative artists please turn to page 30. *First complete Philadelphia Orchestra performances This program runs approximately 1 hour, 50 minutes, and will be performed without an intermission. These performances are made possible in part by the generous support of the William Penn Foundation and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Additional support has been provided by the Presser Foundation. 28 I. Devotions before Mass 1. Antiphon: Kyrie eleison 2. Hymn and Psalm: “A Simple Song” 3. Responsory: Alleluia II. First Introit (Rondo) 1. Prefatory Prayers 2. Thrice-Triple Canon: Dominus vobiscum III. Second Introit 1. In nomine Patris 2. Prayer for the Congregation (Chorale: “Almighty Father”) 3. Epiphany IV. Confession 1. Confiteor 2. Trope: “I Don’t Know” 3. Trope: “Easy” V. Meditation No. 1 VI. Gloria 1. Gloria tibi 2. Gloria in excelsis 3. Trope: “Half of the People” 4. Trope: “Thank You” VII. Mediation No. 2 VIII. Epistle: “The Word of the Lord” IX. Gospel-Sermon: “God Said” X. Credo 1. Credo in unum Deum 2. Trope: “Non Credo” 3. Trope: “Hurry” 4. Trope: “World without End” 5. Trope: “I Believe in God” XI. Meditation No. 3 (De profundis, part 1) XII. -

2017–2018 Season Artist Index

2017–2018 Season Artist Index Following is an alphabetical list of artists and ensembles performing in Stern Auditorium / Perelman Stage (SA/PS), Zankel Hall (ZH), and Weill Recital Hall (WRH) during Carnegie Hall’s 2017–2018 season. Corresponding concert date(s) and concert titles are also included. For full program information, please refer to the 2017–2018 chronological listing of events. Adès, Thomas 10/15/2017 Thomas Adès and Friends (ZH) Aimard, Pierre-Laurent 3/8/2018 Pierre-Laurent Aimard (SA/PS) Alarm Will Sound 3/16/2018 Alarm Will Sound (ZH) Altstaedt, Nicolas 2/28/2018 Nicolas Altstaedt / Fazil Say (WRH) American Composers Orchestra 12/8/2017 American Composers Orchestra (ZH) 4/6/2018 American Composers Orchestra (ZH) Anderson, Laurie 2/8/2018 Nico Muhly and Friends Investigate the Glass Archive (ZH) Angeli, Paolo 1/26/2018 Paolo Angeli (ZH) Ansell, Steven 4/13/2018 Boston Symphony Orchestra (SA/PS) Apollon Musagète Quartet 2/16/2018 Apollon Musagète Quartet (WRH) Apollo’s Fire 3/22/2018 Apollo’s Fire (ZH) Arcángel 3/17/2018 Andalusian Voices: Carmen Linares, Marina Heredia, and Arcángel (SA/PS) Archibald, Jane 3/25/2018 The English Concert (SA/PS) Argerich, Martha 10/20/2017 Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia (SA/PS) 3/22/2018 Itzhak Perlman / Martha Argerich (SA/PS) Artemis Quartet 4/10/2018 Artemis Quartet (ZH) Atwood, Jim 2/27/2018 Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra (SA/PS) Ax, Emanuel 2/22/2018 Emanuel Ax / Leonidas Kavakos / Yo-Yo Ma (SA/PS) 5/10/2018 Emanuel Ax (SA/PS) Babayan, Sergei 3/1/2018 Daniil -

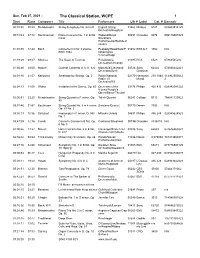

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Sun, Feb 07, 2021 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 09:23 Mendelssohn String Symphony No. 02 in D English String 01460 Nimbus 5141 083603514129 Orchestra/Boughton 00:12:2347:12 Stenhammar Piano Concerto No. 1 in B flat Widlund/Royal 00391 Chandos 9074 095115907429 minor Stockholm Philharmonic/Rozhdest vensky 01:01:0517:24 Bach Concerto in D for 3 Violins, Peabody/Rood/Sato/P 01652 ESS.A.Y 1002 N/A BWV 1064 hilharmonia Virtuosi/Kapp 01:19:2909:47 Sibelius The Swan of Tuonela Philadelphia 01095 RCA 6528 07863565282 Orchestra/Ormandy 01:30:4629:00 Mozart Clarinet Concerto in A, K. 622 Marcellus/Cleveland 03728 Sony 62424 074646242421 Orchestra/Szell Classical 02:01:1621:57 Karlowicz Serenade for Strings, Op. 2 Polish National 02170 Harmonia 278 1088 314902505612 Radio-TV Mundi 2 Orchestra/Wit 02:24:13 11:08 Weber Invitation to the Dance, Op. 65 Orchestra of the 03176 Philips 420 812 028942081222 Vienna People's Opera/Bauer-Theussl 02:36:5123:25 Mendelssohn String Quartet in F minor, Op. Talich Quartet 06241 Calliope 9313 794881725922 80 03:01:4631:57 Beethoven String Quartet No. 8 in E minor, Smetana Quartet 00270 Denon 7033 N/A Op. 59 No. 2 03:35:1310:56 Schubert Impromptu in F minor, D. 935 Mitsuko Uchida 04691 Philips 456 245 028945624525 No. 1 03:47:0912:16 Corelli Concerto Grosso in B flat, Op. Cantilena/Shepherd 00794B Chandos 8336/7/8 N/A 6 No. 5 04:00:5514:27 Mozart Horn Concerto No. -

Notes from the Editor Bruce Gleason University of St

Research & Issues in Music Education Volume 9 Number 1 Research & Issues in Music Education, v.9, Article 1 2011 2011 Notes from the Editor Bruce Gleason University of St. Thomas, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://ir.stthomas.edu/rime Part of the Music Education Commons, and the Music Pedagogy Commons Recommended Citation Gleason, Bruce (2011) "Notes from the Editor," Research & Issues in Music Education: Vol. 9 : No. 1 , Article 1. Available at: http://ir.stthomas.edu/rime/vol9/iss1/1 This Notes from the Editor is brought to you for free and open access by UST Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research & Issues in Music Education by an authorized editor of UST Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gleason: Notes from the Editor A main element guiding conversations in last spring’s University of St. Thomas undergraduate Music of the U.S.: Oral and Written Traditions course was Alan Merriam’s functions of music as he delineated them in The Anthropology of Music. While I was introduced to Merriam’s work as a graduate student, I have long thought that this information would be a great component of undergraduate education, and I was pleased to find that students engaging with these ideas before embarking on their careers resulted in thoughtful discussions. As the class moved through the Sacred Harp, Mahalia Jackson, J.D. Sumner and the Blackwood Brothers, Sonny Terry, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, the Fisk Jubilee Singers, Pete Seeger, Scott Joplin, Glen Miller, George Gershwin, John Philip Sousa, Patsy Cline, Leonard Bernstein, Samuel Barber, Amy Beach, Aaron Copland, Esperanza Spalding, F. -

Honoring Itzhak Perlman

The Trustees of the Westport Library are pleased to present the twenty-second for the evening™ Honoring Itzhak Perlman REMARKS Iain Bruce President, Board of Trustees Bill Harmer Executive Director, Westport Library TRIBUTES AND PERFORMANCES HONORING ITZHAK PERLMAN American String Quartet Peter Winograd, violin Daniel Avshalomov, viola Laurie Carney, violin Wolfram Koessel, cello Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) String Quartet in F Major (1903) IV. Finale: Vif et agité Antonin Dvořák (1841-1904) Piano Quintet No. 2 in A Major, Op. 81 (1887) I. Allegro, ma non tanto Rohan De Silva, pianist A TALK WITH ITZHAK PERLMAN With Andrew C. Wilk, Executive Producer WESTPORT LIBRARY AWARD Presented by Bill Harmer, Executive Director for the evening ™ A Benefit for the Westport Library HONORING ITZHAK PERLMAN Itzhak Perlman rose to fame on the Rohan De Silva Born in Sri Lanka, Rohan Ed Sullivan show, where he performed as a De Silva studied at the Royal Academy child prodigy at just 13 years old. Perlman of Music and at The Juilliard School. He has performed with every major orchestra has collaborated with many of the world’s and at venerable concert halls around the top violinists in recitals, including Pinchas globe. Perlman was granted a Presidential Zukerman, Joshua Bell, Gil Shaham Medal of Freedom by President Obama and Nadja Salerno-Sonnenberg. in 2015, the nation’s highest civilian A highly sought after collaborative pianist honor, a Kennedy Center Honor in 2003, and chamber musician, De Silva has a National Medal of Arts by President collaborated for over twenty years with Itzhak Perlman as his Clinton in 2000 and a Medal of Liberty by President Reagan in 1986.