Fly Times Issue 41, October 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diptera, Phoridae) from Iran

Archive of SID J Insect Biodivers Syst 04(3): 147–155 ISSN: 2423-8112 JOURNAL OF INSECT BIODIVERSITY AND SYSTEMATICS Research Article http://jibs.modares.ac.ir http://zoobank.org/References/578CCEF1-37B7-45D3-9696-82B159F75BEB New records of the scuttle flies (Diptera, Phoridae) from Iran Roya Namaki Khameneh1, Samad Khaghaninia1*, R. Henry L. Disney2 1 Department of Plant Protection, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Tabriz, Tabriz, I.R. Iran. 2 Department of Zoology, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge, CB2 3EJ, U.K. ABSTRACT. The faunistic study of the family Phoridae carried out in northwestern of Iran during 2013–2017. Five species (Conicera tibialis Schmitz, Received: 1925, Dohrniphora cornuta (Bigot, 1857), Gymnophora arcuata (Meigen, 1830), 06 August, 2018 Metopina oligoneura (Mik, 1867) and Triphleba intermedia (Malloch, 1908)) are newly recorded from Iran. The genera Conicera Meigen, 1830, Dohrniphora Accepted: 14 November, 2018 Dahl, 1898, Gymnophora Macquart, 1835 and Triphleba Rondani, 1856 are reported for the first time from the country. Diagnostic characters of the Published: studied species along with their photographs are provided. 20 November, 2018 Subject Editor: Key words: Phoridae, Conicera, Dohrniphora, Gymnophora, Triphleba, Iran, New Farzaneh Kazerani records Citation: Namaki khameneh, R., Khaghaninia, S. & Disney, R.H.L. (2018) New records of the scuttle flies (Diptera, Phoridae) from Iran. Journal of Insect Biodiversity and Systematics, 4 (3), 147–155. Introduction Phoridae with about 4,000 identified insect eggs, larvae, and pupae. The adults species in more than 260 genera, is usually feed on nectar, honeydew and the considered as one of the largest families of exudates of fresh carrion and dung, Diptera (Ament & Brown, 2016). -

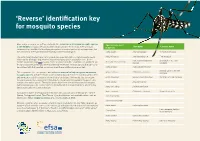

Identification Key for Mosquito Species

‘Reverse’ identification key for mosquito species More and more people are getting involved in the surveillance of invasive mosquito species Species name used Synonyms Common name in the EU/EEA, not just professionals with formal training in entomology. There are many in the key taxonomic keys available for identifying mosquitoes of medical and veterinary importance, but they are almost all designed for professionally trained entomologists. Aedes aegypti Stegomyia aegypti Yellow fever mosquito The current identification key aims to provide non-specialists with a simple mosquito recog- Aedes albopictus Stegomyia albopicta Tiger mosquito nition tool for distinguishing between invasive mosquito species and native ones. On the Hulecoeteomyia japonica Asian bush or rock pool Aedes japonicus japonicus ‘female’ illustration page (p. 4) you can select the species that best resembles the specimen. On japonica mosquito the species-specific pages you will find additional information on those species that can easily be confused with that selected, so you can check these additional pages as well. Aedes koreicus Hulecoeteomyia koreica American Eastern tree hole Aedes triseriatus Ochlerotatus triseriatus This key provides the non-specialist with reference material to help recognise an invasive mosquito mosquito species and gives details on the morphology (in the species-specific pages) to help with verification and the compiling of a final list of candidates. The key displays six invasive Aedes atropalpus Georgecraigius atropalpus American rock pool mosquito mosquito species that are present in the EU/EEA or have been intercepted in the past. It also contains nine native species. The native species have been selected based on their morpho- Aedes cretinus Stegomyia cretina logical similarity with the invasive species, the likelihood of encountering them, whether they Aedes geniculatus Dahliana geniculata bite humans and how common they are. -

Zootaxa, New Records of Haemagogus

Zootaxa 1779: 65–68 (2008) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Correspondence ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2008 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) New records of Haemagogus (Haemagogus) from Northern and Northeastern Brazil (Diptera: Culicidae, Aedini) JERÔNIMO ALENCAR1, FRANCISCO C. CASTRO2, HAMILTON A. O. MONTEIRO2, ORLANDO V. SILVA 2, NICOLAS DÉGALLIER3, CARLOS BRISOLA MARCONDES4*, ANTHONY E. GUIMARÃES1 1Laboratório de Diptera, Departamento de Entomologia, Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, Av. Brasil 4365, CEP: 21045-900 Manguinhos, Rio de Janeiro RJ, Brazil. 2Laboratório de Arbovírus, Instituto Evandro Chagas, Av. Almirante Barroso 492, CEP: 66090-000, Belém, PA, Brazil. 3Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD-UMR182), LOCEAN-IPSL, case 100, 4 Place Jussieu, 75252 Paris Cedex 05, France 4 Departamento de Microbiologia e Parasitologia, Centro de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, 88040- 900 Florianópolis, Santa Catarina, Brazil Haemagogus (Haemagogus) is restricted mostly to the Neotropical Region, including Central America, South America and islands (Arnell, 1973). Of the 24 recognized species of this subgenus, 15 occur in South America, including the Anti- lles. However, the centre of distribution of the genus Haemagogus is Central America, where 19 of the 28 species (including four species of the subgenus Conopostegus Zavortink [1972]) occur (Arnell, 1973). Haemagogus (Hag.) includes species with great significance as vectors of Yellow Fever (YF) virus and other arbovi- rus, both experimentally (Waddell, 1949) and in the field (Vasconcelos, 2003). During entomological surveys from 1982 to 2004, the Arbovirus Laboratory of Evandro Chagas Institute obtained specimens of Haemagogus from several localities not reported in the literature. New records are listed in Table 1 and study localities shown on Figure 1. -

Chironomus Frontpage No 28

CHIRONOMUS Journal of Chironomidae Research No. 30 ISSN 2387-5372 December 2017 CONTENTS Editorial Anderson, A.M. Keep the fuel burning 2 Current Research Epler, J. An annotated preliminary list of the Chironomidae of Zurqui 4 Martin, J. Chironomus strenzkei is a junior synonym of C. stratipennis 19 Andersen, T. et al. Two new Neo- tropical Chironominae genera 26 Kuper, J. Life cycle of natural populations of Metriocnemus (Inermipupa) carmencitabertarum in The Netherlands: indications for a southern origin 55 Lin, X., Wang, X. A redescription of Zavrelia bragremia 67 Short Communications Baranov, V., Nekhaev, I. Impact of the bird-manure caused eutrophication on the abundance and diversity of chironomid larvae in lakes of the Bolshoy Aynov Island 72 Namayandeh, A., Beresford, D.V. New range extensions for the Canadian Chironomidae fauna from two urban streams 76 News Liu, W. et al. The 2nd Chinese Symposium on Chironomidae 81 In memoriam Michailova, P., et al. Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Friedrich Wülker 82 Unidentified male, perhaps of the Chironomus decorus group? Photo taken in the Madrona Marsh Preserve, California, USA. Photo: Emile Fiesler. CHIRONOMUS Journal of Chironomidae Research Editors Alyssa M. ANDERSON, Department of Biology, Chemistry, Physics, and Mathematics, Northern State University, Aberdeen, South Dakota, USA. Torbjørn EKREM, NTNU University Museum, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, NO-7491 Trondheim, Norway. Peter H. LANGTON, 16, Irish Society Court, Coleraine, Co. Londonderry, Northern Ireland BT52 1GX. The CHIRONOMUS Journal of Chironomidae Research is devoted to all aspects of chironomid research and serves as an up-to-date research journal and news bulletin for the Chironomidae research community. -

Species Delimitation in Asexual Insects of Economic Importance: the Case of Black Scale (Parasaissetia Nigra), a Cosmopolitan Parthenogenetic Pest Scale Insect

RESEARCH ARTICLE Species delimitation in asexual insects of economic importance: The case of black scale (Parasaissetia nigra), a cosmopolitan parthenogenetic pest scale insect Yen-Po Lin1,2,3*, Robert D. Edwards4, Takumasa Kondo5, Thomas L. Semple3, Lyn G. Cook2 a1111111111 1 College of Life Science, Shanxi University, Taiyuan, Shanxi, China, 2 School of Biological Sciences, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia, 3 Research School of Biology, Division of a1111111111 Evolution, Ecology and Genetics, The Australian National University, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, a1111111111 Australia, 4 Department of Botany, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington a1111111111 DC, United States of America, 5 CorporacioÂn Colombiana de InvestigacioÂn Agropecuaria (CORPOICA), a1111111111 Centro de InvestigacioÂn Palmira, Valle del Cauca, Colombia * [email protected] OPEN ACCESS Abstract Citation: Lin Y-P, Edwards RD, Kondo T, Semple TL, Cook LG (2017) Species delimitation in asexual Asexual lineages provide a challenge to species delimitation because species concepts insects of economic importance: The case of black either have little biological meaning for them or are arbitrary, since every individual is mono- scale (Parasaissetia nigra), a cosmopolitan phyletic and reproductively isolated from all other individuals. However, recognition and parthenogenetic pest scale insect. PLoS ONE 12 naming of asexual species is important to conservation and economic applications. Some (5): e0175889. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pone.0175889 scale insects are widespread and polyphagous pests of plants, and several species have been found to comprise cryptic species complexes. Parasaissetia nigra (Nietner, 1861) Editor: Wolfgang Arthofer, University of Innsbruck, AUSTRIA (Hemiptera: Coccidae) is a parthenogenetic, cosmopolitan and polyphagous pest that feeds on plant species from more than 80 families. -

Diptera: Culicidae: Aedini) Into New Geographic Areas

European Mosquito Bulletin, 27 (2009), 10-17. Journal of the European Mosquito Control Association ISSN 1460-6127; w.w.w.e-m-b.org First published online 1 October 2009 Recent introductions of aedine species (Diptera: Culicidae: Aedini) into new geographic areas John F. Reinert Center for Medical, Agricultural and Veterinary Entomology (CMAVE), United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, 1600/1700 S.W. 23rd Drive, Gainesville, FL 32608-1067, USA, Email: [email protected]. Abstract Information on introductions to new geographic areas of species in the aedine generic-level taxa Aedimorphus, Finlaya, Georgecraigius, Halaedes, Howardina, Hulecoeteomyia, Rampamyia, Stegomyia, Tanakaius and Verrallina is provided. Key words: Aedimorphus, Finlaya, Georgecraigius atropalpus, Halaedes australis, Howardina bahamensis, Hulecoeteomyia japonica japonica, Rampamyia notoscripta, Stegomyia aegypti, Stegomyia albopicta, Tanakaius togoi, Verrallina Introduction World. Dyar (1928), however, notes that there are no nearly related species in As indicated in the series of papers on the American continent, but many such the phylogeny and classification of in the Old World, especially in Africa, mosquitoes in tribe Aedini (Reinert et and he considered that it was probably al., 2004, 2006, 2008), some aedine the African continent from which the species have been introduced into new species originated”. Christophers also geographical areas in recent times. noted that “The species is almost the Species of Aedini found outside of their only, if not the only, mosquito that, with natural ranges are listed below with their human agency, is spread around the literature citations. whole globe. But in spite of this wide zonal diffusion its distribution is very Introductions of Aedine Species to strictly limited by latitude and as far as New Areas present records go it very rarely occurs beyond latitudes of 45o N. -

Multi-Trophic Level Interactions Between the Invasive Plant

MULTI-TROPHIC LEVEL INTERACTIONS BETWEEN THE INVASIVE PLANT CENTAUREA STOEBE, INSECTS AND NATIVE PLANTS by Christina Rachel Herron-Sweet A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Land Resources and Environmental Sciences MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana May 2014 ©COPYRIGHT by Christina Rachel Herron-Sweet 2014 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION To my parents and grandparents, who instilled in me the value of education and have been my biggest supporters along the way. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special thanks go to my two advisers Drs. Jane Mangold and Erik Lehnhoff for all their tremendous support, advice and feedback during my graduate program. My two other committee members Drs. Laura Burkle and Jeff Littlefield also deserve a huge thank you for the time and effort they put into helping me with various aspects of my project. This research would not have been possible without the dedicated crew of field and lab helpers: Torrin Daniels, Darcy Goodson, Daniel France, James Collins, Ann de Meij, Noelle Orloff, Krista Ehlert, and Hally Berg. The following individuals deserve recognition for their patience in teaching me pollinator identification, and for providing parasitoid identifications: Casey Delphia, Mike Simanonok, Justin Runyon, Charles Hart, Stacy Davis, Mike Ivie, Roger Burks, Jim Woolley, David Wahl, Steve Heydon, and Gary Gibson. Hilary Parkinson and Matt Lavin also offered their expertise in plant identification. Statistical advice and R code was generously offered by Megan Higgs, Sean McKenzie, Pamela Santibanez, Dan Bachen, Michael Lerch, Michael Simanonok, Zach Miller and Dave Roberts. Bryce Christiaens, Lyn Huyser, Gil Gale and Craig Campbell provided instrumental consultation on locating field sites, and the Circle H Ranch, Flying D Ranch and the United States Forest Service graciously allowed this research to take place on their property. -

Nomenclatural Studies Toward a World List of Diptera Genus-Group Names

Nomenclatural studies toward a world list of Diptera genus-group names. Part V Pierre-Justin-Marie Macquart Evenhuis, Neal L.; Pape, Thomas; Pont, Adrian C. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.4172.1.1 Publication date: 2016 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Document license: CC BY Citation for published version (APA): Evenhuis, N. L., Pape, T., & Pont, A. C. (2016). Nomenclatural studies toward a world list of Diptera genus- group names. Part V: Pierre-Justin-Marie Macquart. Magnolia Press. Zootaxa Vol. 4172 No. 1 https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4172.1.1 Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 Zootaxa 4172 (1): 001–211 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Monograph ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2016 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4172.1.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:22128906-32FA-4A80-85D6-10F114E81A7B ZOOTAXA 4172 Nomenclatural Studies Toward a World List of Diptera Genus-Group Names. Part V: Pierre-Justin-Marie Macquart NEAL L. EVENHUIS1, THOMAS PAPE2 & ADRIAN C. PONT3 1 J. Linsley Gressitt Center for Entomological Research, Bishop Museum, 1525 Bernice Street, Honolulu, Hawaii 96817-2704, USA. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Natural History Museum of Denmark, Universitetsparken 15, 2100 Copenhagen, Denmark. E-mail: [email protected] 3Oxford University Museum of Natural History, Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3PW, UK. E-mail: [email protected] Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand Accepted by D. Whitmore: 15 Aug. 2016; published: 30 Sept. 2016 Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0 NEAL L. -

Diptera) Diversity in a Patch of Costa Rican Cloud Forest: Why Inventory Is a Vital Science

Zootaxa 4402 (1): 053–090 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2018 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4402.1.3 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:C2FAF702-664B-4E21-B4AE-404F85210A12 Remarkable fly (Diptera) diversity in a patch of Costa Rican cloud forest: Why inventory is a vital science ART BORKENT1, BRIAN V. BROWN2, PETER H. ADLER3, DALTON DE SOUZA AMORIM4, KEVIN BARBER5, DANIEL BICKEL6, STEPHANIE BOUCHER7, SCOTT E. BROOKS8, JOHN BURGER9, Z.L. BURINGTON10, RENATO S. CAPELLARI11, DANIEL N.R. COSTA12, JEFFREY M. CUMMING8, GREG CURLER13, CARL W. DICK14, J.H. EPLER15, ERIC FISHER16, STEPHEN D. GAIMARI17, JON GELHAUS18, DAVID A. GRIMALDI19, JOHN HASH20, MARTIN HAUSER17, HEIKKI HIPPA21, SERGIO IBÁÑEZ- BERNAL22, MATHIAS JASCHHOF23, ELENA P. KAMENEVA24, PETER H. KERR17, VALERY KORNEYEV24, CHESLAVO A. KORYTKOWSKI†, GIAR-ANN KUNG2, GUNNAR MIKALSEN KVIFTE25, OWEN LONSDALE26, STEPHEN A. MARSHALL27, WAYNE N. MATHIS28, VERNER MICHELSEN29, STEFAN NAGLIS30, ALLEN L. NORRBOM31, STEVEN PAIERO27, THOMAS PAPE32, ALESSANDRE PEREIRA- COLAVITE33, MARC POLLET34, SABRINA ROCHEFORT7, ALESSANDRA RUNG17, JUSTIN B. RUNYON35, JADE SAVAGE36, VERA C. SILVA37, BRADLEY J. SINCLAIR38, JEFFREY H. SKEVINGTON8, JOHN O. STIREMAN III10, JOHN SWANN39, PEKKA VILKAMAA40, TERRY WHEELER††, TERRY WHITWORTH41, MARIA WONG2, D. MONTY WOOD8, NORMAN WOODLEY42, TIFFANY YAU27, THOMAS J. ZAVORTINK43 & MANUEL A. ZUMBADO44 †—deceased. Formerly with the Universidad de Panama ††—deceased. Formerly at McGill University, Canada 1. Research Associate, Royal British Columbia Museum and the American Museum of Natural History, 691-8th Ave. SE, Salmon Arm, BC, V1E 2C2, Canada. Email: [email protected] 2. -

Diptera: Tephritidae) Research in Latin America: Myths, Realities and Dreams

Dezembro, 1999 An. Soc. Entomol. Brasil 28(4) 565 FORUM Fruit Fly (Diptera: Tephritidae) Research in Latin America: Myths, Realities and Dreams MARTÍN ALUJA Instituto de Ecología, A.C., Apartado Postal 63, C.P. 91000, Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico This article is dedicated to J.S. Morgante, R.A. Zucchi, A. Malavasi, F.S. Zucoloto, A.S. Nascimento, S. Bressan, L.A.B. Salles, and A. Kovaleski who have greatly contributed to our knowledge on fruit flies and their parasitoids in Latin America An. Soc. Entomol. Brasil 28(4): 565-594 (1999) A Pesquisa com Moscas-das-Frutas (Diptera: Tephritidae) na América Latina: Mitos, Realidade e Perspectivas RESUMO – Apresento uma avaliação crítica da pesquisa com moscas-das-frutas na América Latina baseada na noção de que muitos mitos e mal-entendidos são transmitidos a estudantes, jovens pesquisadores ou administrações oficiais. Pondero que depois de um esclarecedor início de século, durante o qual muitas descobertas significativas foram feitas sobre a história natural desses insetos, pouco progresso tem sido observado em muitas áreas de pesquisas e manejo de moscas-das-frutas na América Latina durante os últimos 50 anos. Isso tem sido causado em parte pela escassez de estudos sob condições naturais, bem com pela abordagem reducionista utilizada no estudo desses insetos maravilhosos, considerando as espécies individualmente, ou apenas as espécies-praga. Para interromper esse círculo vicioso, proponho que demos mais atenção à história natural das espécies, independente de sua importância econômica, ampliemos o escopo e o período de tempo de nossos estudos, fortaleçamos os fundamentos teóricos e ecológicos das pesquisas com moscas-das-frutas na América Latina e enfatizemos o enfoque comparativo sempre que possível. -

(Diptera, Phoridae) Visiting Flowers of Cryptogorynae Crispatula (Araceae), Including New Species, in China

FRAGMENTA FAUNISTICA 63 (2): 81–118, 2020 PL ISSN 0015-9301 © MUSEUM AND INSTITUTE OF ZOOLOGY PAS DOI 10.3161/00159301FF2020.63.2.081 Records of scuttle flies (Diptera, Phoridae) visiting flowers of Cryptogorynae crispatula (Araceae), including new species, in China R. Henry L. DISNEY Department of Zoology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 3EJ, England; e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The collection of the scuttle flies (Diptera, Phoridae) visiting flowers of Cryptogorynae crispatula (Araceae) caught in Yunnan, China were studied. They were identified to 24 species of which only five were known, seven species are hereby described as new to science and next 13 species cannot be named until linked to their opposite sexes. The following are described. Conicera species female YG, cannot be named until linked to its male. Dohrniphora guangchuni n. sp., Megaselia duolobata n. sp., M. excrispatula n. sp., M. interstinctus n. sp., M. leptotibiarum n. sp., M. menglaensis n. sp., M. shooklinglowae n. sp., Megaselia species Y1 female that cannot be named until linked to its male. The recognition of M. chippensis (Brues, 1911), described from a single female, is augmented. Males of 6 species (Y1-Y6) of Puliciphora Dahl, cannot be named until linked to their females and 5 species of Woodiphora Schmitz. Key words: Phoridae, China, Yunnan, new species. INTRODUCTION Low Shook Ling (Paleoecology Group, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Menglun, Mengla) caught the insects visiting flowers of Cryptogorynae crispatula (Araceae) in Yunnan, China and sent me the scuttle flies (Diptera, Phoridae) for identification. These represent 24 species of which 5 were known species, 6 are new species that are described below and 13 species that cannot be named until linked to their opposite sexes. -

The Distribution and Zoogeography of Freshwater Ostracoda (Crustacea

Bijdragen tot de Dierkunde, 54 (1): 25-50 — 1984 Amsterdam Expeditions to the West Indian Islands, Report 38. The distribution and zoogeography of freshwater Ostracoda (Crustacea) in the West Indies, with emphasis on species inhabiting wells by Nico W. Broodbakker Institute of Taxonomie Zoology, University of Amsterdam, P.O. Box 20125, 1000 HC Amsterdam, The Netherlands Summary Résumé The distribution of Ostracoda in islands of discute freshwater the On la distribution des Ostracodes dulcicoles sur les the West Indies and part of the Venezuelan mainland is îles des Indes Occidentales et dans certaines zones de discussed. The ostracod fauna of wells and epigean Venezuela. La faune d’Ostracodes des puits et des habitats habitats Some Certaines des is compared. species, e.g. Cypretta spp. are épigés est comparée. espèces (par exemple found often in others significantly more wells, are only espèces de Cypretta) sont trouvées nettement plus souvent found in and dans des d’autres epigean habitats, e.g. Hemicypris spp. Cypris puits, (par exemples Hemicypris spp. et subglobosa. Some species are found significantly more often Cypris subglobosa) sont rencontrées seulement dans des in others to habitats il epigean habitats, e.g. Stenocypris major, seem épigés. Ensuite, y a des espèces nettement plus have and trouvées dans les habitats no preference, e.g. Physocypria affinis Cypridopsis souvent épigés (Stenocypris major tandis spp. par exemple), que d’autres (exemples: Physocypria occurrence of Ostracoda and other faunal semblent avoir de Joint groups affinis et Cypridopsis spp.) ne pas préfé- in wells is studied, especially for hadziid amphipods, which rence. are to on small crustaceans.