Special Report Child Labour During the New Coronavirus Pandemic and Beyond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peasant Oaths, Furious Icons and the Quest for Agency: Tracing

15 praktyka teoretyczna 1(39)/2021 } LUKA NAKHUTSRISHVILI (ORCID: 0000-0002-5264-0064) Peasant Oaths, Furious Icons and the Quest for Agency: Tracing Subaltern Politics in Tsarist Georgia on the Eve of the 1905 Revolution Part I: The Prose of the Intelligentsia and Its Peasant Symptoms This two-part transdisciplinary article elaborates on the autobiographical account of the Georgian Social-Democrat Grigol Uratadze regarding the oath pledged by protesting peasants from Guria in 1902. The oath inaugurated their mobilization in Tsarist Georgia in 1902, culminating in full peasant self-rule in the “Gurian Republic” by 1905. The study aims at a historical-anthropological assessment of the asymmetries in the alliance formed by peasants and the revolutionary intelligentsia in the wake of the oath as well as the tensions that crystallized around the oath between the peasants and Tsarist officials. In trying to recover the traces of peasant politics in relation to multiple hegemonic forces in a modernizing imperial borderland, the article invites the reader to reconsider the existing assumptions about historical agency, linguistic conditions of subjectivity, and the relation- ship between politics and the material and customary dimen- sions of religion. The ultimate aim is to set the foundations for a future subaltern reading of the practices specific to the peasant politics in the later “Gurian Republic”. The first part of the article starts with a reading of Uratadze’s narration of the 1902 inaugural oath “against the grain”. Keywords: agency, intelligentsia, oath, Orthodox icons, peasantry, political the- ology, Russian Empire, secular studies, speech-act, subaltern praktyka teoretyczna 1(39)/2021 16 I.1. -

Georgian Country and Culture Guide

Georgian Country and Culture Guide მშვიდობის კორპუსი საქართველოში Peace Corps Georgia 2017 Forward What you have in your hands right now is the collaborate effort of numerous Peace Corps Volunteers and staff, who researched, wrote and edited the entire book. The process began in the fall of 2011, when the Language and Cross-Culture component of Peace Corps Georgia launched a Georgian Country and Culture Guide project and PCVs from different regions volunteered to do research and gather information on their specific areas. After the initial information was gathered, the arduous process of merging the researched information began. Extensive editing followed and this is the end result. The book is accompanied by a CD with Georgian music and dance audio and video files. We hope that this book is both informative and useful for you during your service. Sincerely, The Culture Book Team Initial Researchers/Writers Culture Sara Bushman (Director Programming and Training, PC Staff, 2010-11) History Jack Brands (G11), Samantha Oliver (G10) Adjara Jen Geerlings (G10), Emily New (G10) Guria Michelle Anderl (G11), Goodloe Harman (G11), Conor Hartnett (G11), Kaitlin Schaefer (G10) Imereti Caitlin Lowery (G11) Kakheti Jack Brands (G11), Jana Price (G11), Danielle Roe (G10) Kvemo Kartli Anastasia Skoybedo (G11), Chase Johnson (G11) Samstkhe-Javakheti Sam Harris (G10) Tbilisi Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Workplace Culture Kimberly Tramel (G11), Shannon Knudsen (G11), Tami Timmer (G11), Connie Ross (G11) Compilers/Final Editors Jack Brands (G11) Caitlin Lowery (G11) Conor Hartnett (G11) Emily New (G10) Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Compilers of Audio and Video Files Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Irakli Elizbarashvili (IT Specialist, PC Staff) Revised and updated by Tea Sakvarelidze (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator) and Kakha Gordadze (Training Manager). -

World Bank Document

The World Bank Report No: ISR6658 Implementation Status & Results Georgia Secondary & Local Roads Project (P086277) Operation Name: Secondary & Local Roads Project (P086277) Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 16 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: 07-Aug-2011 Country: Georgia Approval FY: 2004 Public Disclosure Authorized Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: EUROPE AND CENTRAL ASIA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): Roads Department of the Ministry of Regional Development and Infrastructure (RDMRDI) Key Dates Board Approval Date 24-Jun-2004 Original Closing Date 31-Oct-2009 Planned Mid Term Review Date 31-Jul-2007 Last Archived ISR Date 07-Aug-2011 Public Disclosure Copy Effectiveness Date 21-Oct-2004 Revised Closing Date 30-Jun-2012 Actual Mid Term Review Date 03-Nov-2006 Project Development Objectives Project Development Objective (from Project Appraisal Document) The Project Development Objectives are to: (i) upgrade and rehabilitate the secondary and local roads network; and (ii) increase Roads Department of the Ministry of regional development and Infrastructure's (RDMRDI's) and local governments' capacity to manage the road network in a cost-effective and sustainable manner. Has the Project Development Objective been changed since Board Approval of the Project? Yes No Public Disclosure Authorized Component(s) Component Name Component Cost Rehabilitation of Secondary and Local Roads 118.50 Strengthening the capacity of the Road Sector Institutions 2.70 Designing and Supervising Road Rehabilitation 6.30 Overall Ratings Previous Rating Current Rating Progress towards achievement of PDO Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Moderately Satisfactory Satisfactory Public Disclosure Authorized Overall Risk Rating Implementation Status Overview The implementation progress and overall safeguard compliance of the project is Satisfactory. -

Elevated Levels of Lead (Pb) Identified in Georgian Spices

Ericson B, et al. Elevated Levels of Lead (Pb) Identified in Georgian Spices. Annals of Global Health. 2020; 86(1): 124, 1–6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.3044 ORIGINAL RESEARCH Elevated Levels of Lead (Pb) Identified in Georgian Spices Bret Ericson*, Levan Gabelaia†, John Keith*, Tamar Kashibadze†, Nana Beraia†, Lela Sturua†,‡ and Ziad Kazzi§ Background: Human lead (Pb) exposure can result in a number of adverse health outcomes, particularly in children. Objective: An assessment of lead exposure sources was carried out in the Republic of Georgia following a nationally representative survey that found elevated blood lead levels (BLLs) in children. Methods: A range of environmental media were assessed in 25 homes and four bazaars spanning five regions. In total, 682 portable X-Ray Fluorescence measurements were taken, including those from cook- ware (n = 53); paint (n = 207); soil (n = 91); spices (n = 128); toys (n = 78); and other media (n = 125). In addition, 61 dust wipes and 15 water samples were collected and analyzed. Findings: Exceptionally high lead concentrations were identified in multiple spices. Median lead concentra- tions in six elevated spices ranged from 4–2,418 times acceptable levels. Median lead concentrations of all other media were within internationally accepted guidelines. The issue appeared to be regional in nature, with western Georgia being the most highly affected. Homes located in Adjara and Guria were 14 times more likely to have lead-adulterated spices than homes in other regions. Conclusions: Further study is required to determine the source of lead contamination in spices. Policy changes are recommended to mitigate potential health impacts. -

Pilot Integrated Regional Development Programme for Guria, Imereti, Kakheti and Racha Lechkhumi and Kvemo Svaneti 2020-2022 2019

Pilot Integrated Regional Development Programme for Guria, Imereti, Kakheti and Racha Lechkhumi and Kvemo Svaneti 2020-2022 2019 1 Table of Contents List of maps and figures......................................................................................................................3 List of tables ......................................................................................................................................3 List of Abbreviations ..........................................................................................................................4 Chapter I. Introduction – background and justification. Geographical Coverage of the Programme .....6 1.1. General background ........................................................................................................................... 6 1.2. Selection of the regions ..................................................................................................................... 8 Chapter II. Socio-economic situation and development trends in the targeted regions .........................9 Chapter ...........................................................................................................................................24 III. Summary of territorial development needs and potentials to be addressed in targeted regions .... 24 Chapter IV. Objectives and priorities of the Programme ................................................................... 27 4.1. Programming context for setting up PIRDP’s objectives and priorities .......................................... -

Java Printing

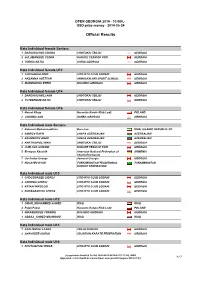

OPEN GEORGIA 2014 - 10.000,- USD prize money - 2014-05-24 Official Results Kata Individual female Seniors Kata Individual female Seniors 1 DARCHIASHVILI DIANA SHOTOKAI TBILISI GEORGIA 2 SULAMANIDZE TEONA KARATE TEAM OF POTI GEORGIA 3 TURKIA NATIA GURIA GEORGIA GEORGIA Kata Individual female U12 Kata Individual female U12 1 CHICHAKUA NINO SITO-RYU CLUB SODANI GEORGIA 2 AKSANNA AVETYAN AKHALKALAKI SPORT SCHOOL GEORGIA 3 MAZMISHVILI ETERI BUSHIDO GEORGIA GEORGIA Kata Individual female U14 Kata Individual female U14 1 DARCHIASHVILI ANA SHOTOKAI TBILISI GEORGIA 2 TUTBERIDZE NATIA SHOTOKAI TBILISI GEORGIA Kata Individual female U16 Kata Individual female U16 1 Harast Kinga Harasuto Karate Klub Lodz POLAND 2 JAKOBIA ANA USHBA GEORGIA GEORGIA Kata Individual male Seniors Kata Individual male Seniors 1 Batavani MohammadReza Bam iran IRAN, ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF 2 AMIROV RAFIK SHAFA AZERBAIJAN AZERBAIJAN 3 AKHMEDOV ANAR SHAFA AZERBAIJAN AZERBAIJAN 3 KHATIASHVILI NIKA SHOTOKAI TBILISI GEORGIA 5 JIJELAVA GURAMI KARATE TEAM OF POTI GEORGIA 5 Eremyan Khachik Armenian National Federation of ARMENIA Shorin-Ryu karate 7 Gochadze George Samurai Georgia GEORGIA 7 HOJAYEV DYAR TURKMENISTAN TRADITIONAL TURKMENISTAN KARATE FEDERATION Kata Individual male U10 Kata Individual male U10 1 CHOGOVADZE GIORGI SITO-RYU CLUB SODANI GEORGIA 2 JAKONIA GIORGI SITO-RYU CLUB SODANI GEORGIA 3 KIFIANI NIKOLOZI SITO-RYU CLUB SODANI GEORGIA 3 BUDAGASHVILI SHOTA SITO-RYU CLUB SODANI GEORGIA Kata Individual male U12 Kata Individual male U12 1 OMAR_MOHAMMED AHMED IRAQ IRAQ 2 Pajak -

Realizing the Urban Potential in Georgia: National Urban Assessment

REALIZING THE URBAN POTENTIAL IN GEORGIA National Urban Assessment ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK REALIZING THE URBAN POTENTIAL IN GEORGIA NATIONAL URBAN ASSESSMENT ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) © 2016 Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City, 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 632 4444; Fax +63 2 636 2444 www.adb.org Some rights reserved. Published in 2016. Printed in the Philippines. ISBN 978-92-9257-352-2 (Print), 978-92-9257-353-9 (e-ISBN) Publication Stock No. RPT168254 Cataloging-In-Publication Data Asian Development Bank. Realizing the urban potential in Georgia—National urban assessment. Mandaluyong City, Philippines: Asian Development Bank, 2016. 1. Urban development.2. Georgia.3. National urban assessment, strategy, and road maps. I. Asian Development Bank. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent. ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. This publication was finalized in November 2015 and statistical data used was from the National Statistics Office of Georgia as available at the time on http://www.geostat.ge The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by ADB in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “country” in this document, ADB does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. -

Short History of Abkhazia and Abkhazian-Georgian Relations

HISTORY AND CONTROVERSY: SHORT HISTORY OF ABKHAZIA AND ABKHAZIAN-GEORGIAN RELATIONS Svetlana Chervonnaya (Chapter 2 from the book” Conflict in the Caucasus: Georgia, Abkhazia and the Russian Shadow”, Glastonbury, 1994) Maps: Andrew Andersen, 2004-2007 Below I shall try to give a short review of the history of Abkhazia and Abkhazian-Georgian relations. No claims are made as to an in-depth study of the remote past nor as to any new discoveries. However, I feel it necessary to express my own point of view about the cardinal issues of Abkhazian history over which fierce political controversies have been raging and, as far as possible, to dispel the mythology that surrounds it. So much contradictory nonsense has been touted as truth: the twenty five centuries of Abkhazian statehood; the dual aboriginality of the Abkhazians; Abkhazia is Russia; Abkhazians are Georgians; Abkhazians came to Western Georgia in the 19th century; Abkhazians as bearers of Islamic fundamentalism; the wise Leninist national policy according to which Abkhazia should have been a union republic, and Stalin's pro-Georgian intrigues which turned the treaty-related Abkhazian republic into an autonomous one. Early Times to 1917. The Abkhazian people (self-designation Apsua) constitute one of the most ancient autochthonous inhabitants of the eastern Black Sea littoral. According to the last All-Union census, within the Abkhazian ASSR, whose total population reached 537,000, the Abkhazians (93,267 in 1989) numbered just above 17% - an obvious ethnic minority. With some difference in dialects (Abzhu - which forms the basis of the literary language, and Bzyb), and also in sub- ethnic groups (Abzhu; Gudauta, or Bzyb; Samurzaqano), ethnically, in social, cultural and psychological respects the Abkhazian people represent a historically formed stable community - a nation. -

Impact on Ethnic Conflict in Abkhazia and South Ossetia

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School February 2019 Soviet Nationality Policy: Impact on Ethnic Conflict in Abkhazia and South Ossetia Nevzat Torun University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons, and the Political Science Commons Scholar Commons Citation Torun, Nevzat, "Soviet Nationality Policy: Impact on Ethnic Conflict in Abkhazia and South Ossetia" (2019). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/7972 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Soviet Nationality Policy: Impact on Ethnic Conflict in Abkhazia and South Ossetia by Nevzat Torun A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts School of Interdisciplinary Global Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Earl Conteh-Morgan, Ph.D. Kees Boterbloem, Ph.D. Bernd Reiter, Ph.D. Date of Approval February 15, 2019 Keywords: Inter-Ethnic Conflict, Soviet Nationality Policy, Self Determination, Abkhazia, South Ossetia Copyright © 2019, Nevzat Torun DEDICATION To my wife and our little baby girl. I am so lucky to have had your love and support throughout the entire graduate experience. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I want to thank Dr. Earl Conteh-Morgan, my advisor, for his thoughtful advice and comments. I would also like to thank my thesis committee- Dr. -

UNICEF Georgia COVID-19 Situation Report 18 September 2020

UNICEF Georgia COVID-19 Situation Report 18 September 2020 HIGHLIGHTS SITUATION IN NUMBERS • On 15 September, UNICEF celebrated the start of another academic year 3,119 with videos of children talking about their experiences as they return to schools, and social media posts of children sharing their views on school reopening. Confirmed cases • An agreement between the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture, and Sports (MoESCS) of Georgia, the Government of Estonia, and UNICEF was signed, which 19 Confirmed deaths focuses on training teachers, school administrators, and educators from 100 schools in distance teaching, learning concepts, and quality education practices. • UNICEF’s partner, MAC Georgia, provided information on health and safety 159 requirements for returning to preschool/school, engaging 110,000 people. Child (<18 years) cases • UNICEF, in partnership with NCDC and with the financial support of USAID, organized a training in Batumi for regional media representatives on COVID-19- 5,014 related health risks and recommendations. Quarantined • UNICEF, in partnership with the Adjara Organization of Georgian Scout Movement, launched a project to involve young scouts in shaping initiatives Abkhazia supporting the COVID-19 response and recovery for adolescents residing in the Confirmed cases - 782 mountainous villages of the Adjara region. Confirmed deaths - 7 • UNICEF launched a new partnership with NGO RHEA Union to organize UNICEF funding gap developmental activities for children and young people with intellectual US$ 1,841,399 (42%) disabilities in Akhalkalaki and Aspindza municipalities. Humanitarian Strategy UNICEF continues to work closely with the Government, WHO, and other United Nations and humanitarian partners to provide technical guidance and support. -

Abkhazia – Historical Timeline

ABKHAZIA – HISTORICAL TIMELINE All sources used are specifically NOT Georgian so there is no bias (even though there is an abundance of Georgian sources from V century onwards) Period 2000BC – 100BC Today’s territory of Abkhazia is part of Western Georgian kingdom of Colchis, with capital Aee (Kutaisi - Kuta-Aee (Stone-Aee)). Territory populated by Georgian Chans (Laz-Mengrelians) and Svans. According to all historians of the time like Strabo (map on the left by F. Lasserre, French Strabo expert), Herodotus, and Pseudo-Skilak - Colchis of this period is populated solely by the Colkhs (Georgians). The same Georgian culture existed throughout Colchis. This is seen through archaeological findings in Abkhazia that are exactly the same as in the rest of western Georgia, with its capital in central Georgian city of Kutaisi. The fact that the centre of Colchian culture was Kutaisi is also seen in the Legend of Jason and the Argonauts (Golden Fleece). They travel through town and river of Phasis (modern day Poti / Rioni, in Mengrelia), to the city of Aee (Kutaisi – in Imereti), where the king of Colchis reigns, to obtain the Golden Fleece (method of obtaining gold by Georgian Svans where fleece is placed in a stream and gold gets caught in it). Strabo in his works Geography XI, II, 19 clearly shows that Georgian Svan tribes ruled the area of modern day Abkhazia – “… in Dioscurias (Sukhumi)…are the Soanes, who are superior in power, - indeed, one might almost say that they are foremost in courage and power. At any rate, they are masters of the peoples around them, and hold possession of the heights of the Caucasus above Dioscurias (Sukhumi). -

The Abkhazian and Mingrelian Principalities: Historical and Demographic Research A

Вестник СПбГУ. История. 2018. Т. 63. Вып. 4 The Abkhazian and Mingrelian Principalities: Historical and Demographic Research A. А. Cherkasov, L. A. Koroleva, S. N. Bratanovskii, A. Valleau For citation: Cherkasov A. А., Koroleva L. A., Bratanovskii S. N., Valleau A. The Abkhazian and Min- grelian Principalities: Historical and Demographic Research. Vestnik of Saint Petersburg University. History, 2018, vol. 63, issue 4, рp. 1001–1016. https://doi.org/10.21638/11701/spbu02.2018.402 This article examines the historical and demographic aspects of the development of the Abkhazian and Mingrelian principalities within the Russian Empire. The attention is drawn to the territorial disputes among rulers over the ownership of Samurzakan. The sources used for this study include documents from the State archives of Krasnodar Krai (Krasnodar, Russian Federation), the Central state historical archive of Georgia (Tbilisi, Georgia), statistical data of the 1800s–1860s on Abkhazia, Mingrelia and Samurzakan, as well as memoirs and diaries of travelers. The authors came to the following conclusions: 1) the uprising of Shikh Mansur in 1785 led to the adoption of new religious rules among the population of Circassia and Abkhazia. As a result, Islam began to spread in Abkhazia. At the time, Islam did not, however, reach Samurzakan and Mingrelia. Both territories remained Christian; 2) as soon as the Abkhazian and Mingrelian principalities were annexed to the Russian Empire, the ruling princes started greatly overestimating the local population rates. They believed that there were on average at least 9–10 people per household on the territories they ruled. In reality, there were 4,7 people per household in Abkhazia and about 7 in Mingrelia; 3) the beginning of the process of decentralization, which was characteristic of the Circassian tribes, can be illustrated Aleksandr A.