What Drives Commodity Price Booms and Busts?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GUIDANCE Position Management Regime for ICE Futures Europe

GUIDANCE Position Management Regime for ICE Futures Europe Soft Commodities September 2018 Copyright IntercontinentalExchange, Inc. 2015. All Rights Reserved www.theice.com Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Accountability Levels 4 3. Delivery Limits 5 4. Delivery Limit Exemptions 5 5. Aggregation 12 6. Enforcement 12 7. Changes to the Accountability Levels, Delivery Limits and Delivery Limit Exemption levels 13 Attachment 1 14 ICE Futures Europe – September 2018 Page 2 of 15 www.theice.com ICE Futures Europe Implementation of the Position Management Regime for ICE Futures Europe Soft Commodities 1. Introduction 1.1. In accordance with Rules A.2 and G.2 the Exchange may adopt such procedures as it deems appropriate to establish. With respect to Rule P.0A, this shall include procedures in respect of any specified delivery/expiry month of any Exchange Contract, or in the case of ICE Futures Europe London Cocoa and Euro Cocoa Contracts, a group of Exchange Contracts, or in respect of a combination of delivery/expiry months thereof, limits on the maximum open position that may be held by a Member for his own account or on behalf of his Client. 1.2. The purpose of this Guidance Document ("Guidance Document") is then to set out, pursuant to Rule P.0A, the procedures and associated guidance in respect of the regime for the monitoring and regulation of ICE Futures Europe London Cocoa and Euro Cocoa (for the purposes of this Guidance, “the Cocoa Contracts”), Robusta Coffee, White Sugar and Containerised White Sugar ( for the purposes of this Guidance “the Sugar Contracts”) and Wheat Futures and Options Contracts (collectively, the “Soft Commodity Contracts”). -

Exploring Environmental Tradeoffs in Soft Commodity Production

Exploring Environmental Tradeoffs in Soft Commodity Production Jen Bowe, Kenny Fahey, Mallory McLaughlin, Julia Ruedig, Sheena VanLeuven, Jay Wolfgram March 2013-April 2014 Modeling Environmental Tradeoffs in Soft Commodity Production 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Transforming Markets: The 2050 Criteria .................................................................................. 5 Beyond The 2050 Criteria: Sustainable Sourcing....................................................................... 6 Commodity Sourcing and Environmental Tradeoffs .................................................................. 7 Project Goals and Objectives .......................................................................................................... 9 Research Methodology ................................................................................................................. 11 Research Sources....................................................................................................................... 11 Commodity Research ................................................................................................................ 12 Environmental Indicators .......................................................................................................... 13 Dimensions of Environmental Tradeoffs ................................................................................. -

Overview of the World's Commodity Exchanges – 2007

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development Overview of the world’s commodity exchanges – 2007 Study prepared by the UNCTAD secretariat United Nations New York and Geneva, 2009 Overview of the world’s commodity exchanges – 2007 Note Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, but acknowledgement is requested. A copy of the publication containing the quotation or reprint should be sent to the UNCTAD secretariat at: Palais des Nations, CH-1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Secretariat. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the secretariat of UNCTAD concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of this authorities or concerning the definition of its frontiers or boundaries. This document was prepared by Leonela Santana-Boado and Adam Gross of the UNCTAD secretariat, with substantial input and research assistance provided by Ms. Leticia Gennes Beltrán. The extensive contributions of Alexander Belozertsev to the sections on Russia and Ukraine are also gratefully acknowledged. Recent publications by the UNCTAD secretariat on the subject of commodity exchanges include “Overview of the world’s commodity -

Financialization and the Returns to Commodity Investments Scott Main

Financialization and the Returns to Commodity Investments Scott Main, Scott H. Irwin, Dwight R. Sanders, and Aaron Smith* April 2018 Forthcoming in the Journal of Commodity Markets *Scott Main is a former graduate student in the Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Scott H. Irwin is the Lawrence J. Norton Chair of Agricultural Marketing, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Dwight R. Sanders is a Professor, Department of Agribusiness Economics, Southern Illinois University-Carbondale. Aaron Smith is a Professor in the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, University of California-Davis. Financialization and the Returns to Commodity Investments Abstract Commodity futures investment grew rapidly after their popularity exploded—along with commodity prices—in the mid-2000s. Numerous individuals and institutions embraced alternative investments for their purported diversification benefits and equity-like returns. We investigate whether the “financialization” of commodity futures markets reduced the risk premiums available to long-only investors in commodities. While energy futures markets generally exhibit a decline in risk premiums after 2004, premiums in all but one non-energy futures market actually increased over the same time period. Overall, the average unconditional return to individual commodity futures markets is approximately equal to zero before and after financialization. Key words: commodity, financialization, futures prices, index fund, investments, risk premium, storable JEL categories: D84, G12, G13, G14, Q13, Q41 Financialization and the Returns to Commodity Investments Introduction Several influential studies published in the last 15 years (e.g., Gorton and Rouwenhorst 2006, Erb and Harvey 2006) concluded that long-only commodity futures investments generate equity-like returns.1 This undoubtedly contributed to the rise of commodity futures from relative obscurity to a common feature in today’s investing landscape. -

Bloomberg Link

Market Commentary 1 Energy 6 Bloomberg Commodity Outlook – May 2018 Edition Metals 9 Agriculture 14 Bloomberg Commodity Index (BCOM) DATA PERFORMANCE: 17 Overview, Commodity TR, Prices, Volatility Broad Commodities Taking the Bull Horns CURVE ANALYSIS: 22 Contango/Backwardation, - Commodity bull appearing young & vibrant vs. mature stock market Roll Yields, Forwards/Forecasts - Carry is a positive but crude oil prices remain extended MARKET FLOWS: 25 - Copper to gold: metals in bull-market transition with stocks Open Interest, Volume, COT, ETFs - Agriculture indicates early recovery from loss-of-faith lows - A potential commodities perfect storm is brewing for 2018 Gold Outlook Webinar – May 3, 10:00 EDT Commodity Investing Outlook Webinar – May 9, 11:00 EDT Data and outlook as of April 30 Mike McGlone – BI Senior Commodity Strategist BI COMD (the commodity dashboard) recipe for higher commodity prices. The nascent Commodity Bull Appears Young and commodity bull is gaining on the elderly stock-market Vibrant Vs. Mature Stock Market rally. A sustained dollar recovery is a key risk, but Performance: April +2.7%, YTD +2.3%, Spot +3.4%. unlikely. (Returns are total return (TR) unless noted) Commodities Looking Beyond April Dollar Gain. (Bloomberg Intelligence) -- Less than three years into a Despite a sharp recovery in the dollar, commodities' recovery, commodities are gaining momentum vs. the divergent strength in April indicates their outperformance decade-long rally in stocks. Favorable demand vs. supply vs. equities and bonds should accelerate. The 2018 and a multiyear price decline vs. bottoming equity-market increase of about 3% through April vs. a flat S&P 500 volatility from the lowest in decades should continue to may be just the beginning as the Bloomberg Commodity favor commodities. -

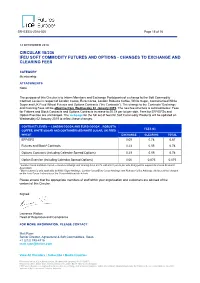

Circular 18/236 Ifeu Soft Commodity Futures and Options - Changes to Exchange and Clearing Fees

SR-ICEEU-2018-025 Page 15 of 16 14 DECEMBER 2018 CIRCULAR 18/236 IFEU SOFT COMMODITY FUTURES AND OPTIONS - CHANGES TO EXCHANGE AND CLEARING FEES CATEGORY Membership ATTACHMENTS None The purpose of this Circular is to inform Members and Exchange Participants of a change to the Soft Commodity Contract Levies in respect of London Cocoa, Euro Cocoa, London Robusta Coffee, White Sugar, Containerized White Sugar and UK Feed Wheat Futures and Options Contracts (“the Contracts”). The change to the Contracts’ Exchange and Clearing Fees will be effective from Wednesday 02 January 2019. The new fee structure is outlined below. Fees for Futures and Block Contracts and Options Contracts increase to £0.78 per lot per side. Fees for EFP/EFSs and Option Exercise are unchanged. The webpage for the full set of fees for Soft Commodity Products will be updated on Wednesday 02 January 2019 to reflect these changes. CONTRACT LEVIES — LONDON COCOA AND EURO COCOA1 , ROBUSTA FEES (£) COFFEE, WHITE SUGAR AND CONTAINERISED WHITE SUGAR, UK FEED WHEAT EXCHANGE CLEARING TOTAL EFP/EFS 0.09 0.78 0.87 Futures and Block2 Contracts 0.23 0.55 0.78 Options Contracts (including Calendar Spread Options) 0.23 0.55 0.78 Option Exercise (including Calendar Spread Options) 0.00 0.075 0.075 1 London Cocoa and Euro Cocoa — futures exchange and clearing fee is £0.79, with £0.01 per lot per side being paid to support the Cocoa Research Association. 2 Block contract is only applicable to White Sugar Arbitrage, London Cocoa/Euro Cocoa Arbitrage and Robusta Coffee Arbitrage. -

Metals Recovery Offsets Energy Decline

Market Commentary 1 Energy 3 Bloomberg Commodity Index (BCOM) Metals 5 Agriculture 7 Tables & Charts – February 2017 Edition DATA PERFORMANCE: 11 Overview, Commodity TR, Prices, Volatility Metals Recovery CURVE ANALYSIS: 15 Contango/Backwardation, Roll Yields, Offsets Energy Decline Forwards/Forecasts MARKET FLOWS: 18 Open Interest, Volume, - Up slightly in 2017 as of February, March may set the BCOM tone for 1H COT, ETFs - Narrowing crude oil and U.S. dollar ranges suggest a volatility pick-up soon - Reviving precious metals lead all sectors with industrials close behind, but appearing extended - Grains grind higher anticipating planting and the potential for some production normalization - Energy is largest index drag due to extended positions and plunging natural gas - Strong metals indicate reflation, but industrials outperforming is more favorable economically Mike McGlone – BI Senior Analyst; Commodities. BI COMD (the commodity dashboard) Broad Commodities Mark Time as S&P 500 Is Top Performer in 2017 Gold & Oil Battle for Leadership Performance: February +0.2%, YTD +.3, Spot 2.4%. (returns are total return (TR) unless noted) The Bloomberg Commodity Index, flat in 2017 on a total return basis and up 2.4% spot can be considered reflationary due to strong metals, but may have negative economic implications if precious continue to outperform. Precious metals, due to snap back from 4Q weakness, are up 10.5% in 2017 vs. 9.9% for industrial metals. MACRO OUTLOOK Some reversion of position and price extremes is at play, notably in energy, down 10.1%. Excessive optimism for Industrial Metals Lagging Precious Indicates Similar further energy-price gains accompanied by record open in Yields. -

Commodity Option Pricing Is a Must-Read for Option Traders, Risk Managers and Quantita- Tive Analysts

“It has been very hard to find a comprehensive option pricing book cover- ing all exchange-traded commodities, until Iain Clark’s book. Commodity Option Pricing is a must-read for option traders, risk managers and quantita- tive analysts. The author combines academic rigor with real-world examples. Practitioners can find an extremely useful toolkit in option pricing andan excellent introduction to various commodities.” Joseph Y. Chen, Chief, Market Analytics, Nexen “Being himself a practitioner with a wealth of experience, Iain knows what is relevant to the daily work of commodities trading desks. He uses his remarkable pedagogical skills to develop the reader’s intuition for the mod- els and products before delving into the practicalities of the commodities markets. Many of the details covered in this book cannot be found elsewhere in the literature. I am pleased to recommend this book to quants and traders, who will soon find themselves relying on it in their daily work.” Paul Bilokon, Director, Deutsche Bank “Option pricing analytics for trading commodity derivatives can be quite different from those of equity and fixed income derivatives. This book fills a gap in current literature by presenting a comprehensive treatise on the risk characteristics associated with pricing and hedging commodity derivatives. The author strikes a fine balance between option pricing theory and financial practice in the markets. The materials are succinctly written, with clear and insightful descriptions of the features of various commodity markets and state-of-the-art pricing models. This book is destined to be a valuable prac- tical guide for practitioners and a useful academic reference for researchers in trading and understanding commodities derivatives.” Yue Kuen Kwok, Professor, Department of Mathematics, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology Commodity Option Pricing For other titles in the Wiley Finance series please see www.wiley.com/finance Commodity Option Pricing A Practitioner’s Guide Iain J. -

Price Volatility Effects on Trading Returns in Agricultural Commodity Derivatives in South Africa

PRICE VOLATILITY EFFECTS ON TRADING RETURNS IN AGRICULTURAL COMMODITY DERIVATIVES IN SOUTH AFRICA Chrisbanard T. Motengwe Masters of Management in Finance and Investment at the Wits Business School at the University of the Witwatersrand Supervisor: Dr. Blessing Mudavanhu May 2013 Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Management in Finance and Investment in the FACULTY OF COMMERCE LAW AND MANAGEMENT WITS BUSINESS SCHOOL at the UNIVERSITY OF THE WITWATERSRAND Supervisor: Signature: DECLARATION I, Chrisbanard Motengwe declare that the research work reported in this dissertation is my own, except where otherwise indicated and acknowledged. It is submitted for the degree of Masters of Management in Finance and Investment at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. This thesis has not, either in whole or in part, been submitted for a degree or diploma to any other universities. Signature of candidate: Date: i Acknowledgements I give thanks firstly to God the Almighty for giving me the strength to complete this project. Special thanks then goes to my family for the support, understanding, time and assistance provided to me over the years. To Chiedza, Lucy, Charles, Kito and Luke, you have been there for me every single step of my life. My heartfelt gratitude goes to Senwes Limited for their contribution to education in South Africa through their Bursary Programme. Likewise, I want to express special thanks to Gerard Van Zyl and Pieter Esterhuysen of Senwes Limited for their visionary leadership and professional support to my career development initiatives. Dr. Blessing Mudavanhu deserves special mention for his commitment to higher education and for providing extraordinary supervision and guidance for this project to reach completion. -

Assessing and Managing Environmental and Social Risks in an Agro-Commodity Supply Chain

Good Practice Handbook Assessing and Managing Environmental and Social Risks in an Agro-Commodity Supply Chain A Editing: Publications Professionals, LLC Design: Studio Grafik Photo Credits: World Bank Group Photo Collection Kathleen Bottriell iStock Photo B GOOD PRACTICE HANDBOOK: E&S RISKS IN AN AGRO-COMMODITY SUPPLY CHAIN Good Practice Handbook Assessing and Managing Environmental and Social Risks in an Agro-Commodity Supply Chain The Handbook has a tabbed structure for easy reference. The following sign posts have been used throughout the Handbook to differentiate specific types of information. This symbol indicates information that is specific to potential or existing IFC clients. This symbol indicates information that explains how to do something in practice. This symbol indicates additional resources or references to support implementation. This symbol indicates key concepts and definitions discussed in the Handbook. Table Of Contents Acknowledgements .....................................................................................iv Introduction ................................................................................................v List of Acronyms .......................................................................................vii Executive Summary ....................................................................................ix Part 1. Agro-Commodity Supply Chains .............................................. 1 Part 2. The Business Case for Managing Environmental and Social Risk in Agro-Commodity Supply -

3 Excellence in Energy Trading 3

2006 BEGAN WITH Russia cutting off gas supplies to the Ukraine and is ending with governments and others digesting the ramifications of the International Energy Agency’s World Energy Outlook, 2006 and the Stern Review on the economics of climate change. Security of supply and environmental concerns now dominate energy market and political agendas. Debate has continued on a Kyoto successor – following the UN Climate Change Conference in Nairobi (COP 12) on strengthening the framework for the years following Kyoto’s initial commitment period (2008-2012). Meanwhile, oil prices reached a nominal high of over US$78 a barrel on July 14th before coming down sharply in the following months. And two of the most active hedge funds engaged in energy derivatives trading were recently forced to liquidate their holdings after experiencing large losses in natural gas price and volatility spread trades. The European Commission has also been busy in establishing better control of the EU ETS following a price collapse earlier in the year because of the over-allocation of permits. It recently announced real cuts in a number of allocation plans. And in January next year, both the Energy and Competition Commissioners will give their verdicts on how the EU intends to structure energy policy and regulation into the future. Meanwhile, the developing world continues its voracious demand for energy with the IEA forecasting that global energy demand will increase by one half between now and 2030 – an average annual rate of 1.6%. Now in their fifth year, the Energy Business Awards reward excellence in a number of key energy business disciplines – to recognise those companies that are making a positive mark on the way energy business is conducted, trading risks mitigated, precious energy resources utilised, energy systems developed, environmental degradation curtailed, energy technology advanced, and energy production and consumption distributed more efficiently and ethically. -

Exchange & Clearing

Energy & Soft Commodity Products Exchange & Clearing Fee Energy Products — Transaction Fees (Per Side Per Lot) Contract Levies — Brent, Gasoil, Low Sulphur Gasoil, WTI, Permian WTI, Dubai, Heating Oil, Fee ($) RBOB Gasoline, ASCI & ASCI Differential Exchange Clearing Total Cash Settlement — 0.09 0.09 Deliveries (Gasoil & Low Sulphur Gasoil only)1 — 8.00 8.00 Deliveries Permian WTI — 2.50 2.50 Deliveries Permian WTI Storage — 5.00 5.00 EFP/EFS/Block 0.12 1.20 1.32 Futures Contracts 0.25 0.57 0.82 EFP/EFS/Block Permian WTI Storage & Dubai — 1.34 1.34 Futures Contracts Permian WTI Storage & Dubai 1.25 1.34 2.59 Option Contracts (Brent, WTI, Gasoil, Low Sulphur Gasoil, & Permian WTI) 0.25 0.57 0.82 Option Contracts (Dubai) 1.25 1.34 2.59 Option Exercise (Brent, WTI, Gasoil, Low Sulphur Gasoil, Permian WTI, & Dubai) — 0.30 0.30 1 ($2.50 if ADP 2 days prior to first day of each delivery range) Fee (£/lot) Contract Levies - UK Natural Gas (Monthly) Exchange Clearing Total Cash Settlement — — — Deliveries (Per Day) — 0.05 0.05 EFP/EFS/Block 0.04 0.46 0.50 Futures Contracts 0.16 0.34 0.50 Futures Style Option Contracts 0.45 1.05 1.50 Option Contracts (EFP/EFS/Blocks) 0.15 1.35 1.50 Option Exercise — 1.00 1.00 Fee (£/lot) Fee (pence/therm) Contract Levies - UK Natural Gas (Daily) Exchange Clearing Total Exchange Clearing Total Cash Settlement — — — — — — Deliveries (Per Day) — — — — — — EFP/EFS/Block 0.005 0.045 0.05 0.0005 0.0045 0.005 Futures Contracts 0.017 0.033 0.05 0.0017 0.0033 0.005 Fee ($) Per Monthly Lot Contract Levies — Coal Exchange Clearing Total Cash Settlement — 2.00 2.00 EFP/EFS/Block 0.90 8.10 9.00 Futures/Options Contracts 2.75 6.25 9.00 Option Exercise — 2.00 2.00 Fee (£) Per MWH Contract Levies — UK Electricity Exchange Clearing Total Deliveries (includes Elexon fee) — 0.0005 0.0005 EFP/EFS/Block 0.00050 0.00450 0.0050 Futures Contracts 0.00150 0.00350 0.0050 Fee (£/lot) Contract Levies — UK Emissions2 Exchange Clearing Total Futures/Daily Futures 1.05 2.45 3.50 Block/EFP/EFS 0.35 3.15 3.50 U.K.