Nationalism and Bounded Integration: How to Create a European Demos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sovereignty, International Law and Democracy Downloaded from by Guest on 23 September 2021 Samantha Besson*

The European Journal of International Law Vol. 22 no. 2 © EJIL 2011; all rights reserved .......................................................................................... Sovereignty, International Law and Democracy Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ejil/article/22/2/373/540688 by guest on 23 September 2021 Samantha Besson* Abstract In my reply to Jeremy Waldron’s article ‘Are Sovereigns Entitled to the Benefit of the Inter- national Rule of Law?’, I draw upon and in some ways expand Waldron’s important con- tribution to our understanding of the international rule of law. First of all, I suggest that Waldron’s argument about the international rule of law can be used to illuminate how we should understand the legitimate authority of international law over sovereign states, but also how some of sovereign states’ residual independence ought to be protected from legit- imate international law. Secondly, I argue that the democratic pedigree of the international rule of law plays a role when assessing how international law binds democratic sovereign states and whether the international rule of law can and ought to benefit their individual sub- jects. Finally, I emphasize how Waldron’s argument that the international rule of law ought to benefit individuals in priority has implications for the sources of international law and for what sources can be regarded as sources of valid law. 1 Introduction In his article ‘Are Sovereigns Entitled to the Benefit of the International Rule of Law?’, Jeremy Waldron focuses ‘on some of the theoretical issues that arise when we consider the [rule of law] in light of the absence of an international sovereign and the extent to which individual national sovereigns have to fulfil governmental functions in the [international law] regime’ (at 316). -

Varieties of American Popular Nationalism.” American Sociological Review 81(5):949-980

Bonikowski, Bart, and Paul DiMaggio. 2016. “Varieties of American Popular Nationalism.” American Sociological Review 81(5):949-980. Publisher’s version: http://asr.sagepub.com/content/81/5/949 Varieties of American Popular Nationalism Bart Bonikowski Harvard University Paul DiMaggio New York University Abstract Despite the relevance of nationalism for politics and intergroup relations, sociologists have devoted surprisingly little attention to the phenomenon in the United States, and historians and political psychologists who do study the United States have limited their focus to specific forms of nationalist sentiment: ethnocultural or civic nationalism, patriotism, or national pride. This article innovates, first, by examining an unusually broad set of measures (from the 2004 GSS) tapping national identification, ethnocultural and civic criteria for national membership, domain- specific national pride, and invidious comparisons to other nations, thus providing a fuller depiction of Americans’ national self-understanding. Second, we use latent class analysis to explore heterogeneity, partitioning the sample into classes characterized by distinctive patterns of attitudes. Conventional distinctions between ethnocultural and civic nationalism describe just about half of the U.S. population and do not account for the unexpectedly low levels of national pride found among respondents who hold restrictive definitions of American nationhood. A subset of primarily younger and well-educated Americans lacks any strong form of patriotic sentiment; a larger class, primarily older and less well educated, embraces every form of nationalist sentiment. Controlling for sociodemographic characteristics and partisan identification, these classes vary significantly in attitudes toward ethnic minorities, immigration, and national sovereignty. Finally, using comparable data from 1996 and 2012, we find structural continuity and distributional change in national sentiments over a period marked by terrorist attacks, war, economic crisis, and political contention. -

Late Classic Maya Political Structure, Polity Size, and Warfare Arenas

LATE CLASSIC MAYA POLITICAL STRUCTURE, POLITY SIZE, AND WARFARE ARENAS Arlen F. CHASE and Diane Z. CHASE Department of Sociology and Anthropology University of Central Florida Studies of the ancient Maya have moved forward at an exceedingly rapid rate. New sites have been discovered and long-term excavations in a series of sites and regions have provided a substantial data base for interpreting ancient Maya civili- zation. New hieroglyphic texts have been found and greater numbers of texts can be read. These data have amplified our understanding of the relationships among subsistence systems, economy, and settlement to such an extent that ancient Maya social and political organization can no longer be viewed as a simple dichoto- mous priest-peasant (elite-commoner) model. Likewise, monumental Maya archi- tecture is no longer viewed as being indicative of an unoccupied ceremonial center, but rather is seen as the locus of substantial economic and political activity. In spite of these advances, substantial discussion still exists concerning the size of Maya polities, whether these polities were centralized or uncentralized, and over the kinds of secular interactions that existed among them. This is espe- cially evident in studies of aggression among Maya political units. The Maya are no longer considered a peaceful people; however, among some modern Maya scholars, the idea still exists that the Maya did not practice real war, that there was little destruction associated with military activity, and that there were no spoils of economic consequence. Instead, the Maya elite are portrayed as engaging predo- minantly in raids or ritual battles (Freidel 1986; Schele and Mathews 1991). -

Politics2021

politics 2021 new and recent titles I polity Page 7 Page 13 Page 13 Page 3 Page 11 Page 7 Page 51 Page 2 Page 6 CONTENTS Ordering details General Politics ............................................ 2 Books can be ordered through our website www.politybooks.com or via: Customer Care Center, John Wiley & Sons Inc. Introductory Texts ....................................... 16 9200 KEYSTONE Crossing STE 800 INDIANAPOLIS, IN 46209-4087 Toll-Free: (877) 762-2974 Fax: (877) 597-3299 Global and Comparative Politics .................. 18 John Wiley & Sons Ltd. European Distribution Centre, New Era Estate, Oldlands Way, Environmental Politics ................................. 19 Bognor Regis, WEST SUSSEX. PO22 9NQ, UK Freephone (UK only): 0800 243407 Overseas callers: +44 1243 843291 Political Economy ....................................... 22 Fax: +44 (0) 1243 843302 Email: [email protected] For Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Luxembourg and Liechtenstein: War and International Security ..................... 28 Phone: +49 6201 606152 Fax: +49 6201 606184 Email: [email protected] Conflict Resolution and Peacebuilding .......... 29 For Australia, New Zealand and Pacific Islands: Toll-free within Australia: 1800 777 474 Toll-free with New Zealand: 0800 448 200 Phone: +61 7 33548455 Development and and Human Rights ............ 30 UK and European Politics ............................ 31 Inspection Copies Most paperback editions featured in this catalogue are Russian Politics ........................................... 32 available for inspection. A maximum of three books may be considered for relevant courses with at least 12 students. A reply form must be returned to this effect. Middle Eastern Politics ................................ 33 Phone (US & Canada): (800) 225-5945 Email: ccopy@wiley,com Freephone (UK only): 0800 243407 Email: [email protected] Phone (Rest of World): +44 1243 843294 Asian Politics ............................................. -

The Myth of the Nation-State: Theorizing Society and Polities in a Global Era

034428 Walby 3/7/2003 10:31 am Page 529 Sociology Copyright © 2003 BSA Publications Ltd® Volume 37(3): 529–546 [0038-0385(200308)37:3;529–546;034428] SAGE Publications London,Thousand Oaks, New Delhi The Myth of the Nation-State: Theorizing Society and Polities in a Global Era ■ Sylvia Walby University of Leeds ABSTRACT The analysis of globalization requires attention to the social and political units that are being variously undermined, restructured or facilitated by this process. Sociology has often assumed that the unit of analysis is society, in which economic, political and cultural processes are coterminous, and that this concept maps onto that of nation-state.This article argues that the nation-state is more mythical than real.This is for four reasons: first, there are more nations than states; second, sev- eral key examples of presumed nation-states are actually empires; third, there are diverse and significant polities in addition to states, including the European Union and some organized religions; fourth, polities overlap and rarely politically saturate the territory where they are located. An implication of acknowledging the wider range and overlapping nature of polities is to open greater conceptual space for the analysis of gender and ethnicity in analyses of globalization. Finally the article re-conceptualizes ‘polities’ and ‘society’. KEY WORDS difference / globalization / nation-state / polities / theory Introduction odern societies have often been equated with nation-states, although pre- modern social associations have been conceptualized differently M (Giddens, 1984; Habermas, 1989; Meyer et al., 1997). But nation-states are actually very rare as existing social and political forms, even in the modern era. -

"Segmentary State" and Politics of Centralization in Medieval Ayudhya

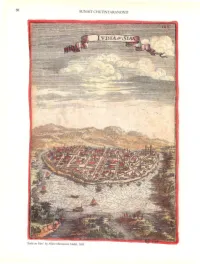

88 SUNAIT CHUTINT ARANOND "Iudia ou Sian" by A llain Mannesson Mallet, 1683. "MANDALA," "SEGMENTARY STATE" AND POLITICS OF CENTRALIZATION IN MEDIEVAL AYUDHYA SUNAIT CHUTINTARANOND DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY, FACULTY OF ARTS CHULALONGKORN UNIVERSITY theory is based on the. assumption that the king, by One of the most common uses of the term mandala is nature, aspires to conquest, an~ that the adjacent king defined as follows in every standard Sanskrit-English diction is his enemy-for the two are not in immediate com ary: "A circular orb, globe, wheel, ring, circumference, any petition and the other neighbor of the enemy would also stand to bendfit from the weakening of the latter. thing round or circular."1 However, this term means "circle" in Surround and conquer.8 many senses:2 in its geo-cosmological connotation, it is the circle of continents around the central mountain of the universe- My primary concern is not, however, to provide any Mount Meru;3 in a ritual sense, it is borrowed to describe any detailed discussion regarding the origins and the diagram of magic circle used in sorcery;4 in politics, it is the circle of a king's Kautilya's mandala construction, which have already been illus near and distant neighbors.5 The political meaning of the term trated in ancient Sanskrit manuscripts and extensively described mandala is directly illustrated in the Arthasastra of Kautilya (a in books on Indian political philosophy.9 Instead, I am inter Machiavellian Hindu text on political management tradition ested in the ways in which Kautilya's theory of mandala has been ally attributed to Kautilya at the end of the fourth century B.C., interpreted by historians for the purpose of studying ancient but, in fact, at least as likely to represent a school compiled at states in South and Southeast Asia. -

Society State and Polity: a Survey

Society State and Polity: A Survey Indian civil polity is almost as old as that of Babylonia and has lasted, like that of China, longer than any other. It is founded on the dictum enunciated by Rāmadāsa in his Dāsabodha (I.10.25) that ‘man is free and cannot be subjected by force’. We have discussed society, state, ruler and polity with this vocabulary — samāja, rājya, rājā and rāja tantra (pālana vyavasthā or governance). When a large number of human beings live together, there is need for some rules and regulations because human nature is such that matsya nyāya , ‘the big fish eats the small fish’, prevails, i.e., it is in the nature of things that the strong will exploit the weak. So since early days, there is a realization in India that there has to be a ‘society’ governed by some commonly agreed rules and regulations. However, such a ‘society’ is only loosely regulated — it is governed by customs and practices, not by laws. Therefore, some more rigorous organization is needed, a system called ‘state’ in political thought, a political system with a legal sanction and foundation, a system ruled by law. A ‘state’, rājya , has several dimensions — the duties / rights of the ruled and the rulers, the rules of governance and the rules that govern the rulers and the ruled. In the same way, a ‘society’, samāja , has its components, the different jātis or communities, and functional units that we may call varṇas or castes. A society has its structural units such as family, institutions such as marriage, and customs and practices such as inheritance, rituals of marriage and mourning, and finally a framework of individual and social life as for example the āśrama vyavasthā laid down in the Hindu society as an ideal organization of an individual’s life. -

The Mandala Culture of Anarchy: the Pre-Colonial Southeast Asian International Society Manggala, Pandu Utama

www.ssoar.info The Mandala Culture of Anarchy: the Pre-Colonial Southeast Asian International Society Manggala, Pandu Utama Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Manggala, P. U. (2013). The Mandala Culture of Anarchy: the Pre-Colonial Southeast Asian International Society. Journal of ASEAN Studies, 1(1), 1-13. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-441509 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC Lizenz (Namensnennung- This document is made available under a CC BY-NC Licence Nicht-kommerziell) zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu (Attribution-NonCommercial). For more Information see: den CC-Lizenzen finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/deed.de The Mandala Culture of Anarchy: The Pre-Colonial Southeast Asian International Society Pandu Utama Manggala Australian National University, Australia Abstract Throughout the years, study on pre-colonial Southeast Asian international relations has not garnered major attention because it had long been seen as an integral part of the China- centred tribute system. There is a need to provide greater understanding of the uniqueness of the international system as different regions have different ontologies to comprehend its dynamics and structures. This paper contributes to the pre-colonial Southeast Asian literature by examining the interplay that had existed between pre-colonial Southeast Asian empires and the hierarchical East Asian international society, in particular during the 13th- 16th Century. The paper argues that Southeast Asian international relations in pre-colonial time were characterized by complex political structures with the influence of Mandala values. -

World Society-World Polity Theory Bibliography John Boli, Selina R. Gallo-Cruz, and Matthew D. Mathias Department of Sociology

World Society-World Polity Theory Bibliography John Boli, Selina R. Gallo-Cruz, and Matthew D. Mathias Department of Sociology, Emory University 1 September 2009 Contact information: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abu Sharkh, Miriam. 2002. History and Results of Labor Standard Initiatives: An Event History and Panel Analysis of the Ratification Patterns, and Effects, of the International Labor Organization’s First Child Labor Convention. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Political and Social Science, Free University of Berlin. Ahrne, Göran, and Nils Brunsson. 2009. “Internationale Metaorganisationen und ihre Mitglieder” (“International Mea-organizations and their Members”). Forthcoming in Klaus Dingwerth, Dieter Kerwer, and Andreas Nölke (eds.), Die Organisierte Welt. Internationale Beziehungen und Organisationsforschung (The Organized World: International Relations and Organizations Research). Baden-Baden: Nomos. Ahrne, Göran, and Nils Brunsson. 2008. Meta-Organizations. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar. Ahrne, Göran, Nils Brunsson, and Kristina Tamm Hallström, eds. 2007. Organizing the World. Organization (special issue) 14 (5). Ahrne, Göran, and Nils Brunsson. 2006. “Organizing the World.” Pp. 74-94 in Marie-Laure Djelic and Kerstin Sahlin-Andersson (eds.), Transnational Governance: Institutional Dynamics of Regulation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Ahrne, Göran, and Nils Brunsson. 2005. “Organizations and meta-organizations.” Scandinavian Journal of Management 21 (4): 429-49. Ahrne, Göran, and Nils Brunsson. 2004. “Soft Regulation from an Organizational Perspective.” Pp. 171-90 in Ulrika Mörth (ed.), Soft Law in Governance and Regulation: An Interdisciplinary Analysis. Cheltenham, UK, and Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar. Albert, Mathias. 2005. “Politik der Weltgesellschaft und Politik der Globalisierung: Überlegungen zur Emergenz von Weltstaatlichkeit” (“Politics of World Society and Politics of Globalization: Notes on the Emergence of World Statehood”). -

A Comparative 'Study of Thirty City-State Cultures

A Comparative 'Study of Thirty City-State Cultures An Investigation Conducted by the Copenhagen Polis Centre Edited by MOGENSHERMAN HANSEN Historisk-filosofiske Skrifter 21 Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabemes Selskab The Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters Commission Agent: C.A. Reitzels Forlag Copenhagen 2000 Aztec Citv-States1 Central Mexico before the Spanish conquest was the pology in the 1970s and 1980s focused on the interac- setting for two extended cycles of sociopolitical evo- tions among small political units as crucial elements lution. These cycles, which lasted for several cen- in the overall dynamics of social change in agrarian turies, were characterized by population increase, the societies (Adams [1975]; Price [1977]; Renfrew & spread of complex urban society across the landscape, Cherry [1986]). The concept of city-state culture and the growth of powerful states. Only the second builds on this earlier work and highlights the most cycle, culminating in Aztec society as encountered by interesting and dynamic aspects of city-states cross- Hemando CortCs in 1519, was characterized by a city- culturally. state culture. The first cycle involved the growth of Approaches to city-states that focus on form alone, Classic-period Teotihuacan, a territorial state whose with insufficient consideration of processes of interac- large urban capital ruled a small empire in central tion or city-state culture, fall into the danger of in- Mexico. The fall of Teotihuacan around AD 700 initi- cluding nearly all examples of ancient states. The ated some four centuries of political decentralization recent book, The Archaeology of City-States: Cross- and ruralization of settlement. -

The Kurdish Regional Constitution

The Kurdish Regional Constitution within the Framework of the Iraqi Federal Constitution: A Struggle for Sovereignty, Oil, Ethnic Identity, and the Prospects for a Reverse Supremacy Clause Michael J. Kelly* The Kurd has no friend but the mountain. ―Ancient Kurdish proverb * Professor of Law, Associate Dean for Faculty Research & International Programs, Creighton University School of Law. B.A., J.D., Indiana University; LL.M., Georgetown University. Chair (2009-2010) of the Association of American Law Schools Section on National Security Law and President of the U.S. National Chapter of L‟Association Internationale de Droit Pénal. Professor Kelly teaches comparative constitutional law as well as a range of international law courses. Many thanks to Danielle Pressler, Alexander Dehner and Christopher Roth for their research assistance, and to Professors Mark Tushnet, Haider Hamoudi, Gregory McNeal, Sean Watts and Afsheen John Radsan for their thoughtful comments. Thanks also to the Kurdish Regional Government for hosting me. The views expressed here are those of the author, not the AALS nor the AIDP. 707 708 PENN STATE LAW REVIEW [Vol. 114:3 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .................................................................................. 708 I. THE KURDS: A STATELESS PEOPLE......................................... 710 A. Iraqi Kurdistan ................................................................ 719 B. Stability from Political Equilibrium .................................. 720 II. KURDISH AUTONOMY UNDER THE IRAQI FEDERAL -

The Politics of Iraqi Kurdistan: Towards Federalism Or Secession?

The Politics of Iraqi Kurdistan: Towards Federalism or Secession? Ala Jabar Mohammed April 2013 Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Government at the University of Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia i Abstract Scholars of ethnic conflict resolution have suggested various approaches to addressing the ethnic right to self-determination, especially when an ethnic group perceives itself to be a nation. These approaches include autonomy, federation and confederation. One neglected area is whether an ethno-nation feels that one of these institutional designs can accommodate their aspirations or is secession their ultimate goal, especially in an ethnically divided society? For this reason, the politics of Iraqi Kurdistan presents as a particularly interesting case study with which to examine the tension between internal self-determination and secession, and test the utility of one such design, namely, federalism. Since 1992 Iraqi Kurdistan has been in a politically more advantageous position than other parts of Greater Kurdistan in Turkey, Syria and Iran because population has gained an autonomous status. On 5 April 1991, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 688 setting up the Safe Haven for the Kurds in Iraq by the Allies following the second Gulf War, thus acting to prevent the Kurds from facing an uncertain future. The Kurds used this opportunity to elect their first parliament on 19 May 1992 and to establish the Kurdistan Regional Government. Since 1992 this Kurdish polity has been evolving, but its possible political futures have not been empirically examined in-depth. Thus, this thesis focuses on the issue of the future of Kurds in Iraq.