The History of Fabric & Textiles Textiles Are Defined As the Yarns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

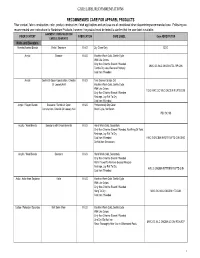

Care Label Recommendations

CARE LABEL RECOMMENDATIONS RECOMMENDED CARE FOR APPAREL PRODUCTS Fiber content, fabric construction, color, product construction, finish applications and end use are all considered when determining recommended care. Following are recommended care instructions for Nordstrom Products, however; the product must be tested to confirm that the care label is suitable. GARMENT/ CONSTRUCTION/ FIBER CONTENT FABRICATION CARE LABEL Care ABREVIATION EMBELLISHMENTS Knits and Sweaters Acetate/Acetate Blends Knits / Sweaters K & S Dry Clean Only DCO Acrylic Sweater K & S Machine Wash Cold, Gentle Cycle With Like Colors Only Non-Chlorine Bleach If Needed MWC GC WLC ONCBIN TDL RP CIIN Tumble Dry Low, Remove Promptly Cool Iron If Needed Acrylic Gentle Or Open Construction, Chenille K & S Turn Garment Inside Out Or Loosely Knit Machine Wash Cold, Gentle Cycle With Like Colors TGIO MWC GC WLC ONCBIN R LFTD CIIN Only Non-Chlorine Bleach If Needed Reshape, Lay Flat To Dry Cool Iron If Needed Acrylic / Rayon Blends Sweaters / Gentle Or Open K & S Professionally Dry Clean Construction, Chenille Or Loosely Knit Short Cycle, No Steam PDC SC NS Acrylic / Wool Blends Sweaters with Embelishments K & S Hand Wash Cold, Separately Only Non-Chlorine Bleach If Needed, No Wring Or Twist Reshape, Lay Flat To Dry Cool Iron If Needed HWC S ONCBIN NWOT R LFTD CIIN DNID Do Not Iron Decoration Acrylic / Wool Blends Sweaters K & S Hand Wash Cold, Separately Only Non-Chlorine Bleach If Needed Roll In Towel To Remove Excess Moisture Reshape, Lay Flat To Dry HWC S ONCBIN RITTREM -

Fibers and Fabrics; TX335 .A1 U6 NO

KitlQRr Bureau of Standards Reference book' no' to ygjgtv |Oi Admin. Bldg. taken from the library, gmp STATES Ite.WMENT OF COMMERCE PUBLICATION A11ID3 Db3SbD All103063560 Blandford, Josephlne/FIbers and fabrics; TX335 .A1 U6 NO. 1, 1970 C.1 NBS-PUB-R 1 ^TES ‘‘•‘‘'/I'ti'i'.1'1' 1: BBB8 MB A Consumer’s Guide from the Mational Bureau of Standards NBS CIS 1 IIIIShSs Fibers and Fabrics by Josephine M. Blandford and Lois M. Gurel INFORMATION ABOUT NATURAL AND MAN-MADE FIBERS AND FABRICS TO MEET YOUR PARTICULAR NEEDS. NBS CONSUMER INFORMATION SERIES 1 Editor: James E. Payne Issued November 1970 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Maurice H. Stans, Secretary Rocco C. Siciliano, Under Secretary Myron Tribus, Assistant Secretary for Science and Technology NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS A Consumer’s Lewis M. Branscomb, Director GUIDE FROM THE) NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, U.S. DEPARTMENT Washington, D.C. 20402. OF COMMERCE Price 65 cents. NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS APR 1 0 1971 FOREWORD Technology is changing not only the products you buy, but the marketplace as well. Unfortunately, this is not an unmixed blessing. Products are constantly being improved, but designs are complicated, quality is vari¬ able, and good advice is hard to get. Modern stores and merchandising bring you a wide variety of products; but the large number of choices and the lack of dependable infor¬ mation often make shopping a confusing and frustrating experience. A generation ago the merchant was likely to be a friend of the family. -

Handle and Comfort Characteristics of Cotton Core Spun Lycra and Polyester/ Lycra Fabrics for Application As Blouse Nirmala Varghese and G

Volume 8, Issue 4, Spring2014 Handle and Comfort Characteristics of Cotton Core Spun Lycra and Polyester/ Lycra Fabrics for Application as Blouse Nirmala Varghese and G. Thilagavathi Department of Apparel & Fashion Technology PSG College of Technology Tamil Nadu, India ABSTRACT Stretchable plain woven fabrics are developed with 60s cotton core spun Lycra and polyester Lycra twisted yarn (91D) in weft with cotton, silk and polyester in warp. The influence of fabric specifications on thermal comfort, low stress mechanical properties, primary and total hand value is analyzed. The results indicated that cotton core spun Lycra woven with polyester warp provided higher value of thermal conductivity, air permeability and water vapor permeability. The woven stretch fabrics produced with polyester warp, cotton core spun Lycra and polyester Lycra in weft has excellent aesthetic and drape properties. These fabrics have higher tensile resilience, tensile strain, lower shear rigidity, superior primary hand and a higher total hand value of 4.08 and 3.93 respectively and are best suitable for women’s blouse. Keywords: Cotton core spun Lycra, polyester/Lycra, woven stretch, fabric handle, sari blouse Introduction Lycra and polyester/lycra twisted yarn. Several studies have been carried out Stretch is often the most important investigating the physical properties of core property of textiles that contribute to wearer spun yarn, cotton/lycra and properties of the comfort. The stretch yarn and fabrics are fabrics containing different rates of spandex widely used and preferred by the people in yarns. Core spun cotton/spandex shows high the last few years all over the world because resiliency property than 100% cotton yarns, of their stretch ability and shape retention due to its soft and rubbery isocyanate properties. -

Fabric Supplier List

FABRIC SUPPLIER LIST CANADA Kendor Textiles Ltd 1260 Cliveden Ave Delta BC V3M 6Y1 Canada 604.434.3233 [email protected] www.kendortextiles.com Fabrics Available: Fabric supplier. Eco-friendly. Organic. Knits: solids, prints, yarn dyes and warp. Wovens: solids and yarn dyes. End Use: activewear, bottomweights, medical, lingerie, childrenswear, swimwear, rainwear, skiwear and uniform. Natural & eco items include cottons, bamboo's, modals, linens, hemps, organic cottons & organic linens. Technical items include waterproof/breathable soft shells, antibacteric & wicking polyester & recycled polyesters. Is a proud representative of the British Millerain line of waxed cottons and wools, and are able to provide custom souring. Minimums: Carries stock. In-stock minimum: 5 yards/color. Minimum order for production: 10 yards/color. Gordon Fabrics LTD #1135-6900 Graybar Rd. Richmond BC Canada 604.275.2672 [email protected] Fabrics Available: Fabric Supplier. Importer. Jobber. Carries stock. Knits & Wovens: solids, prints, yarn dyes and novelties. End Use: activewear, borromweights, eveningwear/bridal, medical, lingerie and childrenswear. Minimums: In stock minimum 1 yard. Minimum order for production varies. StartUp Fashion Supplier List 2016 – Page 1 CHINA Ecopel (HX) Co., Ltd. China +86 216.767.9686 www.ecopel.cn Fabrics Available: Fake fur and leather garments. End Uses: Childrenswear, Menswear, Other, Womenswear. Minimums: Min. order 50-100 m Hangzhou New Design Source Textile Co., Ltd. China +86 057.182.530528 Fabrics Available: Knits, Polyester/Man-Made, Prints. End Uses: Juniors Fashion, Menswear, Womenswear. Minimums: Min order 50 m. Nantong Haukai Textile Co., Ltd. China +86 513.890.78626 www.huakaitex.com Fabrics Available: Cotton, Linen. End Uses: Corporatewear/Suiting, Menswear, Womenswear. -

Commission Briefing Package: Status Update-16 CFR Part 1610 Rule

Briefing Package Status Update: 16 CFR Part 1610 Rule Update and Consideration for Adding Spandex Fibers to the List of Currently Exempted Fibers from Testing September 30, 2020 The views expressed in this report are those of the CPSC staff, and they have not been reviewed or approved by, and may not necessarily reflect the views of, the Commission. THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1) Team Members: Paige Witzen, LS Allyson Tenney, LS Weiying Tao, LS Emily Maling, LS Andrew Lock, LS Carolyn Carlin, CRE Meridith Kelsch, OGC Jacqueline Campbell, ES David Miller, EPI Cynthia Gillham, EC 2 THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1) Table of Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. i Briefing Memorandum ........................................................................................................ iii Introduction ...........................................................................................................................1 Statutory and Regulatory Requirements .................................................................................2 CPSC Activities Regarding Burden Reduction and 16 CFR Part 1610 ...................................3 Incident Data .........................................................................................................................4 Market -

Effect of Fiber Content on Comfort Properties of Cotton/Spandex

SSRG International Journal of Polymer and Textile Engineering (SSRG-IJPTE) – Volume X Issue Y–Month 2018 Effect of Fiber Content on Comfort Properties of Cotton/Spandex, Rayon/Spandex, and Polyester/Spandex Single Jersey Knitted Fabrics Shuvo Kumar Kundu#1, Usha Chowdhary*2 #Graduate Student, * Professor, Fashion Merchandising and Design, Central Michigan University 228 EHS, Central Michigan University, Mount Pleasant, MI 48858, USA 1 [email protected] 2 [email protected] Abstract transmission of cotton–synthetic blend ([1]- [3]). Comfort influences consumers’ buying Stretch in cotton can be incorporated by knit decision regarding textile and apparel product. In this construction and blending with spandex. Polyester and study, comfort related properties of three different rayon (viscose) are also commonly used fabrics in single jersey knit fabrics were tested. All fabrics had apparel that can have enhanced stretch through knit 5% spandex as a common factor. Spandex was structure and addition of spandex. blended with cotton, rayon and polyester. Three Comfort can be function of several structural comfort related attributes studied for the investigation and performance attributes [2]. Structural attributes were stretch and recovery, air permeability and could include fiber content and fabric construction. horizontal wicking. Presence of spandex in knitted Spandex is an elastomeric fiber and adds comfort structure expected to enhance stretch and recovery through its stretching ability ([4], [5]). Knits offer hence flexibility and comfort in garments. Therefore, higher stretch than woven materials. Knit with the purpose of this study was to determine the spandex can provide added comfort for the wearer. influence of cotton, rayon and polyester on selected Performance attributes such as air permeability, comfort properties of textile materials. -

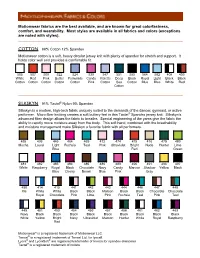

Motionwear Color Chart.Pdf

Motionwear fabrics are the best available, and are known for great colorfastness, comfort, and wearability. Most styles are available in all fabrics and colors (exceptions are noted with styles). COTTON 88% Cotton 12% Spandex Motionwear cotton is a soft, heavy circular jersey knit with plenty of spandex for stretch and support. It holds color well and provides a comfortable fit. 505 507 509 522 524 539 547 551 555 564 592 408 409 White Red Pink Butter Periwinkle Candy Violette Deep Black Royal Light Black Black Cotton Cotton Cotton Cotton Cotton Pink Cotton Sea Cotton Blue Blue White Red Cotton SILKSKYN 91% Tactel® Nylon 9% Spandex Silkskyn is a modern, high-tech fabric uniquely suited to the demands of the dancer, gymnast, or active performer. Micro fiber knitting creates a soft buttery feel in this Tactel® Spandex jersey knit. Silkskyn’s advanced fiber design allows the fabric to breathe. Special engineering of the yarns give the fabric the ability to rapidly move moisture away from the body. This soft hand, combined with the breathability and moisture management make Silkskyn a favorite fabric with all performers. 435 436 445 464 469 472 474 475 476 479 480 Mocha Laurel Light Fuchsia Teal Pink Ultraviolet Bright Nude Hunter Lime Blue Red Green 481 482 483 484 485 486 489 490 491 496 497 White Raspberry Royal Black Chocolate Navy Candy Maroon Shadow Yellow Black Blue Cherry Brown Blue Pink Gray 498 414 415 441 442 443 444 446 447 448 Iris White White Black Black Maroon Black Black Chocolate Chocolate Royal Chocolate Pink Lime Pink Fuchsia Teal Pink Teal 449 451 453 454 456 457 458 461 462 463 Navy Black Black Black Black Black Black Black Black Black White Yellow Bright Navy Ultraviolet Maroon Hunter White Royal Raspberry Red Motionwear® is a registered trademark of Motionwear LLC. -

The Fiber Year 2007/08” Is the Eighth Issue to Describe in Detail Developments in the World Manmade Fiber, Spun Yarn and Nonwovens Industry

Issue 8 – May 2008 The Fiber Year 2007 / 08 A World Survey on Textile and Nonwovens Industry Dear Readers, We are on the right course. It was our aim to position Oerlikon as the new corporate umbrella brand as well as the global market and innovative leader in the textile sector. And we have been more than successful in doing so last year – in particular thanks to your confidence in our per- formance. Therefore, we would like to thank you warmly, for example for your overwhelming feedback referring the ITMA 2007. There, you did not only show great interest in our innovative products. But you also accepted in a very positive way our five brands which we presented there under one roof for the first time. And we promise you: Oerlikon Barmag, Oerlikon Neumag, Oerlikon Saurer, Oerlikon Schlafhorst and Oerlikon Textile Components will continue to display their combined expertise in the fields of nonwovens, man-made fibres, natural fibres, twisting, embroidery and components. Dr. Carsten Voigtländer CEO Oerlikon Textile There are good reasons that you will profit from this: Our reorganisation creates synergies that will be of direct benefit for you. We offer leading total solutions all along the textile value-added chain and we are the number one player in almost all of our markets. Thus, we will offer you future- and solution-oriented products and services that are even more efficient. For we are able to advance product innovations and technological optimisation across the process chain stronger than before. One example for this is our e-save energy efficiency programme. -

Fabrics Guide

FABRICS GUIDE DOS AND DON’TS. 100 % Cotton or Organic Cotton: EasyWeed (Regular, Stretch or Extra), Glitter, Foil, Rhinestones, StripFlock, Brick, etc. Normal temperature settings apply 100% Polyester (Uncoated): EasyWeed (Regular, Stretch or Extra), Glitter, Foil, Rhinestones, StripFlock, Brick, etc. Normal temperature settings apply Not recommended to use a Teflon pillow as they leave heat marks Recommended if using EasyWeed to use stretch DO NOT USE vinyl remover unless covering the area with another design; it will stain 100% Polyester (Coated): EasyWeed Extra, Glitter, Foil, Rhinestones, StripFlock, Brick, Holographic Normal temperature settings apply Not recommended to use a Teflon pillow as they leave heat marks EasyWeed regular or stretch WILL COME OFF! DO NOT USE vinyl remover unless covering area with other design; it will stain 100% Spandex: EasyWeed Stretch, Glitter (might crack), Foil, Rhinestones Normal temperature settings apply DO NOT USE vinyl remover; this will destroy material, causing a massive discoloration 100% Nylon, Lycra, Spandex or Rayon: Not recommended for pressing Genuine Leather or Plastic: Not recommended for pressing; it will be ruined 50/50 Cotton-Poly Blend: EasyWeed (Regular, Stretch or Extra), Glitter, Foil, Rhinestones, StripFlock, Brick, etc. Normal temperature settings apply 51-79% Cotton Blends: EasyWeed (Regular, Stretch or Extra), Glitter, Foil, Rhinestones, StripFlock, Brick, etc. Normal temperature settings apply Cotton – Poly Blend (49% or less Cotton): EasyWeed (Regular, Stretch or Extra), -

PINE CREST FABRICS IN-STOCK FABRIC CATALOG Swim – Active - Fashion

2021 / 2022 PINE CREST FABRICS IN-STOCK FABRIC CATALOG swim – active - fashion 6015 NE 80th Ave. Portland, OR 97218 (503) 254 – 1353 www.pinecrestfabrics.com IN-STOCK RECYCLED FABRICS www.pinecrestfabrics.com 2 CLOUD REC 13 COLLECTION • 88% Recycled Mipan® Regen Nylon / 12% Creora® HighClo Spandex • 58/59″ • 135GSM The Cloud Rec 13 is perfect for swimwear lining and intimate apparel. Not only does it have a soft hand, but it helps save the planet. Available by the single roll in 35 colors! TTR106C1 TTR106C2 TTR106C3 WHITE BLACK TAN www.pinecrestfabrics.com 3 VIRTUE REC COLLECTION • 78% Repreve® Recycled Polyester / 22% Creora® HighClo Spandex • 58/60″ • 205GSM This Virtue Repreve® Recycled Polyester Spandex is an eco-friendly TTR101C3A TTR101C8A TTR101C9A TTR101C5A fabric that is perfect for swimwear and CHERRY RED NEON PINK VIOLETTA CLOUD performance wear. Available by the single roll in 24 additional colors! TTR101C7A TTR101C4A TTR101C 6A TTR101C2 PEACOCK DEEP TEAL COBALT BLACK www.pinecrestfabrics.com 4 BLACK RECYCLED FABRICS TTR105C2 TTR102C1 Black Valor Black Endurance Heavy • 88% Repreve® Recycled • 72% Repreve® Recycled Polyester / 12% Creora® Polyester / 28% Creora® HighClo Spandex HighClo Spandex • 58/60″ • 58/60″ • 260GSM • 300GSM Black Valor Repreve® Recycled Black Endurance Heavy Repreve® Polyester Spandex is an Eco- Recycled Polyester Spandex is an Friendly fabric is perfect for eco-friendly fabric that is perfect for performance wear. An ideal the activewear market. This fabric is sublimation print base! a terrific print base for leggings. Available by single roll in 32 colors! www.pinecrestfabrics.com 5 ENDURANCE COLLECTION • 83% Repreve® Recycled Polyester / 17% Creora® HighClo Spandex • 58/60” • 265GSM Endurance Repreve® Recycled Polyester Spandex is perfect for any activewear market! TTR100C2 TTR100C3 TTR100C4 TTR100C6 WHITE MINERAL RED DEEP LICHEN GREEN ORCHID MIST Stay on-trend while also helping to save the planet. -

Analysis of Spandex/Cotton Elastomeric Properties: Spinning and Applications

International Journal of Composite Materials 2012, 2(2): 11-16 DOI: 10.5923/j.cmaterials.20120202.03 Analysis of Spandex/Cotton Elastomeric Properties: Spinning and Applications Kunal Singha Department of Textile Technology, Panipat Institute of Engineering & Technology, Harayana, India Abstract The spandex or lycra (chemically polyuthrene) is become a very popular and emerges as the only choice for the case of the elastomeric behaviour and can be easily blended with different other fiber like cotton, wool, silk or also can be mixed with other manmade polymer like nylon, polyester etc. The elastomeric behaviour of this type of elastomeric proper- ties comes due to the soft and hard segmental attachment inside the spandex fiber. The ratio of the soft and the hard segment is very important to determine the elastomeric or mechanical properties (elongation, relaxation) of the spandex fiber blend with natural material like cotton fiber (spandex/cotton blend). Keywords Spandex (Lycra), Polyuthrene, Elastomeric Properties, Ratio of Soft and Hard Segment, Elongation, Re- laxation, Spandex/Cotton Blend glycol while the other is a stiff di-isocyanate (Figure 1). The 1. Introduction macro-glycol can be polyester, polyether, polycarbonate, polycaprolactone or some combination of these. These are Spadex (Lycra, named by Dupont) better known as elas- long chain polymers, which have hydroxyl groups (-OH) on tane fiber is better known as elastane (polyurethane or PU) is both ends (Figure 1). The important feature of these mole- very frequently use in the women’s and men’s innerwear, cules is that they are long and flexible[1, 6]. This part of the outerwear, and active wear. -

Controlling the Spandex Yarn Draw Ratio

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 22 July 2020 High Efficiency Covering Technology for Covered Yarns Production: Controlling the Spandex Yarn Draw Ratio Pei Feng1,2, Dashuang Liu1, Chongchang Yang1,2 1. College of Mechanical Engineering, Donghua University, Shanghai, 201620, China 2. Engineering Research Center of Advanced Textile Machinery, Ministry of Education, Shanghai,201620, China Corresponding author: Chongchang Yang; Email: [email protected]; Abstract: A new covered yarn system is proposed in this manuscript by controlling the tension of the spandex elastic yarn drawing.. By analyzing the relationship between the draw ratio and yarn tension, it has been verified that the new tension controlled drawing system is feasible and results in yarns with superior quality and process stability. Keywords: Tension Controlled; Elastic Fiber; Draw Ratio; Spandex Covered Yarns Introduction Spandex Covered Yarns consist of bare spandex as the core material wrapped with various yarns and fibers. In the covering process, the spandex is drawn at a constant ratio, fed through a hollow spindle and covered with a covering yarn from a flanged bobbin [1,2]. Its properties, particularly elongation, elasticity and appearance, depend on the draft parameters, revolution speed and the covering yarn selection [3]. The critical factors responsible for various properties of spandex covered yarns are the pre-draft of spandex and core spun yarn twist multiplier, which should be used in reasonable way to match the purpose of the fabrics [4]. Drawing roller is the most critical part of drawing system which controls the equipment performance and product quality in the textile machinery. The drawing system also has great influence on the quality of semi-finished products, evenness of the yarn and the appearance of finished products.