Marcia Pointon No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Name of Object: Apollo and Daphne Location: Rome, Italy Holding

Name of Object: Apollo and Daphne Location: Rome, Latium, Italy Holding Museum: Borghese Gallery Date of Object: 1622–1625 Artist(s) / Craftsperson(s): Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598, Naples-1680, Rome) Museum Inventory Number: CV Material(s) / Technique(s): Marble Dimensions: h: 243 cm Provenance: Borghese Collection Type of object: Sculpture Description: This sculpture is considered one of the masterpieces in the history of art. Bernini began sculpting it in 1622 after he finished The Rape of Proserpina. He stopped working on it from 1623 to 1624 to sculpt David, before completing it in 1625. With notable technical accuracy, the natural agility of this work shows the astonishing moment when the nymph turns into a laurel tree. The artist uses his exceptional technical skill to turn the marble into roots, leaves and windswept hair. Psychological research, combined with typically Baroque expressiveness, renders the emotion of Daphnes terror, caught by the god in her desperate journey, still ignorant of her ongoing transformation. Apollo, thinking he has achieved his objective, is caught in the moment he becomes aware of the metamorphosis, before he is able to react, watching astonished as his victim turns into a laurel tree. For Apollos head, Bernini looked to Apollo Belvedere, which was in the Vatican at the time. The base includes two scrolls, the first containing the lines of the distich by Maffeo Barberini, a friend of Cardinal Scipione Borghese and future Pope Urban VIII. It explores the theme of vanitas in beauty and pleasure, rendered as a Christian moralisation of a profane theme. The second scroll was added in the mid-1700s. -

Fillegorical Truth-Telling Via the Ferninine Baroque: Rubensg Material Reality

Fillegorical Truth-telling via the Ferninine Baroque: RubensgMaterial Reality bY Maria Lydia Brendel fi Thesls submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial folfiilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of flrt History McGIll Uniuerslty Montréal, Canada 1999 O Marfa lgdlo Brendel, 1999 National Library Bibliothèque nationale of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K 1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Your hls Votre roferenw Our fib Notre réMrencs The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothêque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sel1 reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in rnicrofonn, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantiaî extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Table of Contents Bcknowledgements .............................................................................................................. -

Impressionist & Modern

Impressionist & Modern Art New York | November 17, 2020 Impressionist & Modern Art New York | Tuesday November 17, 2020 at 5pm EST BONHAMS INQUIRIES BIDS COVID-19 SAFETY STANDARDS 580 Madison Avenue New York Register to bid online by visiting Bonhams’ galleries are currently New York, New York 10022 Molly Ott Ambler www.bonhams.com/26154 subject to government restrictions bonhams.com +1 (917) 206 1636 and arrangements may be subject Bonded pursuant to California [email protected] Alternatively, contact our Client to change. Civil Code Sec. 1812.600; Services department at: Bond No. 57BSBGL0808 Preeya Franklin [email protected] Preview: Lots will be made +1 (917) 206 1617 +1 (212) 644 9001 available for in-person viewing by appointment only. Please [email protected] SALE NUMBER: contact the specialist department IMPORTANT NOTICES 26154 Emily Wilson on impressionist.us@bonhams. Please note that all customers, Lots 1 - 48 +1 (917) 683 9699 com +1 917-206-1696 to arrange irrespective of any previous activity an appointment before visiting [email protected] with Bonhams, are required to have AUCTIONEER our galleries. proof of identity when submitting Ralph Taylor - 2063659-DCA Olivia Grabowsky In accordance with Covid-19 bids. Failure to do this may result in +1 (917) 717 2752 guidelines, it is mandatory that Bonhams & Butterfields your bid not being processed. you wear a face mask and Auctioneers Corp. [email protected] For absentee and telephone bids observe social distancing at all 2077070-DCA times. Additional lot information Los Angeles we require a completed Bidder Registration Form in advance of the and photographs are available Kathy Wong CATALOG: $35 sale. -

Julius S. Held Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3g50355c No online items Finding aid for the Julius S. Held papers, ca. 1921-1999 Isabella Zuralski. Finding aid for the Julius S. Held 990056 1 papers, ca. 1921-1999 Descriptive Summary Title: Julius S. Held papers Date (inclusive): ca. 1918-1999 Number: 990056 Creator/Collector: Held, Julius S (Julius Samuel) Physical Description: 168 box(es)(ca. 70 lin. ft.) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Research papers of Julius Samuel Held, American art historian renowned for his scholarship in 16th- and 17th-century Dutch and Flemish art, expert on Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. The ca. 70 linear feet of material, dating from the mid-1920s to 1999, includes correspondence, research material for Held's writings and his teaching and lecturing activities, with extensive travel notes. Well documented is Held's advisory role in building the collection of the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico. A significant portion of the ca. 29 linear feet of study photographs documents Flemish and Dutch artists from the 15th to the 17th century. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical / Historical Note The art historian Julius Samuel Held is considered one of the foremost authorities on the works of Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. -

Vision, Touch, and the Poetics of Bernini's Apollo and Daphne Author(S): Andrea Bolland Source: the Art Bulletin, Vol

Desiderio and Diletto: Vision, Touch, and the Poetics of Bernini's Apollo and Daphne Author(s): Andrea Bolland Source: The Art Bulletin, Vol. 82, No. 2 (Jun., 2000), pp. 309-330 Published by: College Art Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3051379 Accessed: 29/10/2009 07:49 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=caa. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. College Art Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Art Bulletin. http://www.jstor.org Desiderio and Diletto: Vision, Touch, and the Poetics of Bernini's Apollo and Daphne AndreaBolland The gods, that mortal beauty chase, Daphne and to the subtleties of Bernini's statue. -

PROVISIONAL PROGRAM HNA Conference 2022

PROVISIONAL PROGRAM HNA Conference 2022 Amsterdam and The Hague, Netherlands HNA CONFERENCE 2022 Amsterdam and The Hague 2-4 June 2022 Program committee: Stijn Bussels, Leiden University (chair) Edwin Buijsen, Mauritshuis Suzanne Laemers, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History Judith Noorman, University of Amsterdam Gabri van Tussenbroek, University of Amsterdam | City of Amsterdam Abbie Vandivere, Mauritshuis and University of Amsterdam KEYNOTE LECTURES ClauDia Swan, Washington University A Taste for Piracy in the Dutch Republic 1 The global baroque world was a world of goods. Transoceanic trade routes compounded travel over land for commercial gain, and the distribution of wares took on global dimensions. Precious metals, spices, textiles, and, later, slaves were among the myriad commodities transported from west to east and in some cases back again. Taste followed trade—or so the story tends to be told. This lecture addresses the traffic in global goods in the Dutch world from a different perspective—piracy. “A Taste for Piracy in the Dutch Republic” will present and explore exemplary narratives of piracy and their impact and, more broadly, the contingencies of consumption and taste- making as the result of politically charged violence. Inspired by recent scholarship on ships, shipping, maritime pictures, and piracy this lecture offers a new lens onto the culture of piracy as well as the material goods obtained by piracy, and how their capture informed new patterns of consumption in the Dutch Republic. Jan Blanc, University of Geneva Dutch Seventeenth Century or Dutch Golden Age? Words, concepts and ideology Historians of seventeenth-century Dutch art have long been accustomed to studying not only works of art and artists, but also archives and textual sources. -

October 17, 2017 – January 21, 2018 Rubens the Power Of

OCTOBER 17, 2017 – RUBENS JANUARY 21, 2018 THE POWER OF TRANSFORMATION Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) was a star during his lifetime, and he remains a star today. His name is synonymous with an entire period, the Baroque. But his novel pictorial inventions continue to influence and appeal to artists. Now two leading museums, the Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien and the Städel Museum in Frankfurt, are hosting a major exhibition entitled “Rubens. The Power of Transformation”. The exhibition focuses on some little-studied aspects of Rubens’ creative process, illustrating the profound dialogue he entered into with works produced by other great masters, both precursors and contemporaries, and how this impacted his work over half a century. His use or referencing of works by various artists from different periods is generally not immediately apparent, and the exhibition invites visitors to discover these sometimes surprising correlations and connections by directly comparing the works in question. Comprising artworks in various media, the exhibition brings together paintings, drawings, prints, sculptures and objets d’art. Exemplary groups of works will demonstrate Rubens’ methods, which allowed him to dramatize well-known and popular as well as novel subject matters. This offers a fascinating glimpse into the genesis of his compositions and his surprising changes of motifs, but also how he struggled to find the perfect format and the ideal form. Rubens’ extensive œuvre reflects both the influence of classical sculpture and of paintings produced by artists - both in Italy and north of the Alps - from the late fifteenth century to the Baroque. Selected examples will help to illustrate the powerful creative effort that underpins Rubens’ compositions, and the reaction-chains they, in turn, set off in his artistic dialogue with his contemporaries. -

Bilder-Recycling Mit Rubens

8 Ausstellung aktuell Rubens im Städel 9 Bilder-Recycling mit Rubens Foto: The State Hermitage Museum, Sankt Petersburg Sankt Museum, Hermitage State The Foto: Foto: bpk / RMN – Grand Palais Grand – RMN / bpk Foto: Foto: Rheinisches Bildarchiv Köln Bildarchiv Rheinisches Foto: Peter Paul Rubens: Römisch: Der von Cupido gezähmte Kentaur, Peter Paul Rubens: Kentaur von Cupido gezähmt, Ecce homo, nicht später als 1612, Öl auf Holz 1.–2. Jh. n. Chr., Marmor um 1601/02, schwarze Kreide auf Papier In seinen Werken verarbeitet der barocke Malerstar häufig Heutzutage würde sofort Alarm ausgelöst, und das Aufsichts- abzuwehren scheint, sondern wie ein Vorgriff auf die Pose der personal müsste einschreiten. Anfang des 17. Jahrhunderts Freiheitsstatue wirkt. Motive anderer Künstler. Das führt eine Ausstellung im aber hat es offenbar niemanden gestört, wenn sich ein Besu- Rubens schuf dieses Blatt um 1601/1602 als gerade einmal Frankfurter Städel vor Augen. cher auf den Boden der Vatikanischen Museen direkt unter 24-Jähriger. Selbst bei einer Studie beließ er es also nicht die Laokoon-Gruppe legte. Nur in dieser Position kann Peter beim schlichten Abzeichnen, sondern war schon früh auf TEXT KATINKA FISCHER Paul Rubens die verwegene Untersicht auf den Torso des anti- schöpferischen Mehrwert bedacht. Unbeeindruckt vom ken Helden zu Papier gebracht haben: Der Blick fällt auf ein obersten Leitsatz der Akademie, der die Natur zur idealen übertrieben furchiges Brustmuskel-Gebirge, in eine marmorn Vorlage erklärt, brachte er es anschließend auch damit zu glatte Achselhöhle, gesichtsloses Bartgewölle und einen em- Ruhm und Ehre, dass er sich vom Werk anderer Künstler inspi- porgereckten Arm, der aus dieser Perspektive keine Schlange rieren ließ. -

Beleef De Vlaamse Meesters

BELEEF DE VLAAMSE MEESTERS PROGRAMMA 2018 - 2020 1 De gegevens in deze brochure kunnen wijzigen. Ga voor actuele informatie naar visitflanders.com/flemishmasterstrade. 2 VLAAMSE MEESTERS 2018-2020 OP HET HOOGTEPUNT VAN DE POSTMIDDELEEUWSE ARTIS- TIEKE VERNIEUWING WAS VLAANDEREN DE INSPIRATIEBRON ACHTER DE VERMAARDE KUNSTBEWEGINGEN VAN DIE TIJD: DE VLAAMSE PRIMITIEVEN, DE RENAISSANCE EN DE BAROK. 250 JAAR LANG WAS DEZE REGIO HET TREFPUNT OM DE ALLERGROOTSTE WEST-EUROPESE KUNSTENAARS TE ONT- MOETEN EN HUN WERK TE ZIEN. DRIE KUNSTENAARS IN HET BIJZONDER, VAN EYCK, BRUEGEL EN RUBENS, TRADEN PRO- MINENT OP DE VOORGROND EN VERWIERVEN HUN PLAATS AAN HET FIRMAMENT VAN DE ALLERGROOTSTE MEESTERS ALLER TIJDEN. 3 VLAANDEREN WAS TOEN EEN SMELTKROES VAN KUNST EN CREATIVITEIT, WETENSCHAP EN UITVINDING. OOK NU NOG BRUIST DEZE REGIO VAN VITALITEIT EN VERNIEUWING. Het project “Vlaamse Meesters” is en werkte, de landschappen die is ongetwijfeld veel authentieker op poten gezet voor nieuwsgierige Pieter Bruegel de Oude inspireerden en indrukwekkender als je ze reizigers die graag over anderen en zien en een origineel schilderij van in Vlaanderen zelf ziet, waar de over zichzelf leren. Het is bestemd Eyck op de precieze plek van de kunstwerken tot leven kwamen. voor mensen die, net als de Vlaamse afgebeelde scène ontdekken. Vlaanderen investeert aanzienlijk Meesters in hun tijd, gretig nieuwe in toeristische infrastructuur culturen en nieuwe inzichten en cultuur zodat bezoekers een aftasten. PROJECT ‘VLAAMSE fantastische belevenis te wachten MEESTERS’ 2018-2020 staat. Verder organiseren we een Van 2018 tot 2020 organiseert programma vol kwaliteitsevents Toerisme Vlaanderen een hele reeks Het project ‘Vlaamse Meesters’ focust en tentoonstellingen met activiteiten en evenementen om op het leven en de nalatenschap van internationale weerklank in 2018, bezoekers van over de hele wereld Van Eyck, Bruegel en Rubens, actief 2019 en 2020. -

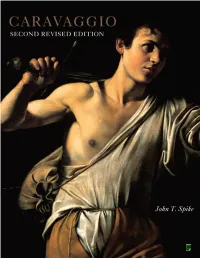

Caravaggio, Second Revised Edition

CARAVAGGIO second revised edition John T. Spike with the assistance of Michèle K. Spike cd-rom catalogue Note to the Reader 2 Abbreviations 3 How to Use this CD-ROM 3 Autograph Works 6 Other Works Attributed 412 Lost Works 452 Bibliography 510 Exhibition Catalogues 607 Copyright Notice 624 abbeville press publishers new york london Note to the Reader This CD-ROM contains searchable catalogues of all of the known paintings of Caravaggio, including attributed and lost works. In the autograph works are included all paintings which on documentary or stylistic evidence appear to be by, or partly by, the hand of Caravaggio. The attributed works include all paintings that have been associated with Caravaggio’s name in critical writings but which, in the opinion of the present writer, cannot be fully accepted as his, and those of uncertain attribution which he has not been able to examine personally. Some works listed here as copies are regarded as autograph by other authorities. Lost works, whose catalogue numbers are preceded by “L,” are paintings whose current whereabouts are unknown which are ascribed to Caravaggio in seventeenth-century documents, inventories, and in other sources. The catalogue of lost works describes a wide variety of material, including paintings considered copies of lost originals. Entries for untraced paintings include the city where they were identified in either a seventeenth-century source or inventory (“Inv.”). Most of the inventories have been published in the Getty Provenance Index, Los Angeles. Provenance, documents and sources, inventories and selective bibliographies are provided for the paintings by, after, and attributed to Caravaggio. -

Vlaamse Meesters 2018-2020

VLAAMSE MEESTERS 2018-2020 BELEEF DE VLAAMSE MEESTERS PROGRAMMA 2018 - 2020 1 VLAAMSE MEESTERS 2018-2020 OP HET HOOGTEPUNT VAN DE POSTMIDDELEEUWSE ARTIS- TIEKE VERNIEUWING WAS VLAANDEREN DE INSPIRATIEBRON ACHTER DE VERMAARDE KUNSTBEWEGINGEN VAN DIE TIJD: DE VLAAMSE PRIMITIEVEN, DE RENAISSANCE EN DE BAROK. 250 JAAR LANG WAS DEZE REGIO HET TREFPUNT OM DE ALLERGROOTSTE WEST-EUROPESE KUNSTENAARS TE ONT- MOETEN EN HUN WERK TE ZIEN. DRIE KUNSTENAARS IN HET BIJZONDER, VAN EYCK, BRUEGEL EN RUBENS, TRADEN PRO- MINENT OP DE VOORGROND EN VERWIERVEN HUN PLAATS AAN HET FIRMAMENT VAN DE ALLERGROOTSTE MEESTERS ALLER TIJDEN. De gegevens in deze brochure kunnen wijzigen. Ga voor actuele informatie naar visitflanders.com of www.flemishmasters.com 2 3 NEDERLAND BRUGGE ANTWERPEN GENT MECHELEN BRUSSEL LEUVEN DUITSLAND FRANKRIJK WALLONIË VLAANDEREN WAS TOEN EEN SMELTKROES VAN KUNST EN CREATIVITEIT, WETENSCHAP EN UITVINDING. OOK NU NOG BRUIST DEZE REGIO VAN VITALITEIT EN VERNIEUWING. Het project “Vlaamse Meesters” is door het huis waar Rubens leefde Veel werken van deze Vlaamse DEZE DRIE HOOGTEPUNTEN Vlaamse primitieven, zoals Jan herfst van 2019 komt Bruegel op poten gezet voor nieuwsgierige en werkte, de landschappen die Meesters kun je over de hele wereld MAG JE NIET MISSEN: van Eycks “Heilige Barbara” en naar Antwerpen, waar het reizigers die graag over anderen en Pieter Bruegel de Oude inspireerden bewonderen, maar de ervaring “Madonna bij de fontein” en Ro- gerenoveerde Museum voor over zichzelf leren. Het is bestemd zien en een origineel schilderij van is ongetwijfeld veel authentieker 1. In 2018 viert de stad Antwerpen gier van der Weydens altaarstuk Schone Kunsten Antwerpen voor mensen die, net als de Vlaamse Eyck op de precieze plek van de en indrukwekkender als je ze haar barokke erfgoed en de “De zeven sacramenten”. -

HNA April 2016 Cover.Indd

historians of netherlandish art NEWSLETTER AND REVIEW OF BOOKS Dedicated to the Study of Netherlandish, German and Franco-Flemish Art and Architecture, 1350-1750 Vol. 33, No. 1 April 2016 Anthony van Dyck, Portrait of a Woman, ca. 1640. Oil on canvas, Speed Art Museum, Louisville (Kentucky); Museum Purchase, Preston Pope Satterwhite Fund Exhibited in Van Dyck: The Anatomy of Portraiture, The Frick Collection, New York, March 2 – June 5, 2016. HNA Newsletter, Vol. 23, No. 2, November 2006 1 historians of netherlandish art 23 S. Adelaide Avenue, Highland Park, NJ 08904 Telephone: (732) 937-8394 E-Mail: [email protected] www.hnanews.org Historians of Netherlandish Art Offi cers President – Amy Golahny (2013-2017) Lycoming College Williamsport PA 17701 Vice-President – Paul Crenshaw (2013-2017) Providence College Department of Art History 1 Cummingham Square Providence RI 02918-0001 Treasurer – David Levine Southern Connecticut State University 501 Crescent Street New Haven CT 06515 European Treasurer and Liaison - Fiona Healy Seminarstrasse 7 D-55127 Mainz Germany Board Members Contents Stephanie Dickey (2013-2017) Arthur DiFuria (2016-2020) President's Message .............................................................. 1 Walter Melion (2014-2018) Obituary ................................................................................. 1 Alexandra Onuf (2016-2020) HNA News ............................................................................2 Bret Rothstein (2016-2020) Gero Seelig (2014-2018) Personalia ..............................................................................