Addax Nasomaculatus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sand Dune Systems in Iran - Distribution and Activity

Sand Dune Systems in Iran - Distribution and Activity. Wind Regimes, Spatial and Temporal Variations of the Aeolian Sediment Transport in Sistan Plain (East Iran) Dissertation Thesis Submitted for obtaining the degree of Doctor of Natural Science (Dr. rer. nat.) i to the Fachbereich Geographie Philipps-Universität Marburg by M.Sc. Hamidreza Abbasi Marburg, December 2019 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Christian Opp Physical Geography Faculty of Geography Phillipps-Universität Marburg ii To my wife and my son (Hamoun) iii A picture of the rock painting in the Golpayegan Mountains, my city in Isfahan province of Iran, it is written in the Sassanid Pahlavi line about 2000 years ago: “Preserve three things; water, fire, and soil” Translated by: Prof. Dr. Rasoul Bashash, Photo: Mohammad Naserifard, winter 2004. Declaration by the Author I declared that this thesis is composed of my original work, and contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference has been made in the text. I have clearly stated the contribution by others to jointly-authored works that I have included in my thesis. Hamidreza Abbasi iv List of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................. 1 1. General Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 7 1.1 Introduction and justification ........................................................................................................ -

Download File

Italy and the Sanusiyya: Negotiating Authority in Colonial Libya, 1911-1931 Eileen Ryan Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 ©2012 Eileen Ryan All rights reserved ABSTRACT Italy and the Sanusiyya: Negotiating Authority in Colonial Libya, 1911-1931 By Eileen Ryan In the first decade of their occupation of the former Ottoman territories of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica in current-day Libya, the Italian colonial administration established a system of indirect rule in the Cyrenaican town of Ajedabiya under the leadership of Idris al-Sanusi, a leading member of the Sufi order of the Sanusiyya and later the first monarch of the independent Kingdom of Libya after the Second World War. Post-colonial historiography of modern Libya depicted the Sanusiyya as nationalist leaders of an anti-colonial rebellion as a source of legitimacy for the Sanusi monarchy. Since Qaddafi’s revolutionary coup in 1969, the Sanusiyya all but disappeared from Libyan historiography as a generation of scholars, eager to fill in the gaps left by the previous myopic focus on Sanusi elites, looked for alternative narratives of resistance to the Italian occupation and alternative origins for the Libyan nation in its colonial and pre-colonial past. Their work contributed to a wider variety of perspectives in our understanding of Libya’s modern history, but the persistent focus on histories of resistance to the Italian occupation has missed an opportunity to explore the ways in which the Italian colonial framework shaped the development of a religious and political authority in Cyrenaica with lasting implications for the Libyan nation. -

Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger a Dissertation Submitted

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Rhythms of Value: Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology by Eric James Schmidt 2018 © Copyright by Eric James Schmidt 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Rhythms of Value: Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger by Eric James Schmidt Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Timothy D. Taylor, Chair This dissertation examines how Tuareg people in Niger use music to reckon with their increasing but incomplete entanglement in global neoliberal capitalism. I argue that a variety of social actors—Tuareg musicians, fans, festival organizers, and government officials, as well as music producers from Europe and North America—have come to regard Tuareg music as a resource by which to realize economic, political, and other social ambitions. Such treatment of culture-as-resource is intimately linked to the global expansion of neoliberal capitalism, which has led individual and collective subjects around the world to take on a more entrepreneurial nature by exploiting representations of their identities for a variety of ends. While Tuareg collective identity has strongly been tied to an economy of pastoralism and caravan trade, the contemporary moment demands a reimagining of what it means to be, and to survive as, Tuareg. Since the 1970s, cycles of drought, entrenched poverty, and periodic conflicts have pushed more and more Tuaregs to pursue wage labor in cities across northwestern Africa or to work as trans- ii Saharan smugglers; meanwhile, tourism expanded from the 1980s into one of the region’s biggest industries by drawing on pastoralist skills while capitalizing on strategic essentialisms of Tuareg culture and identity. -

Terminal Pleistocene Lithic Variability in the Western Negev (Israel): Is There Any Evidence for Contacts with the Nile Valley? Alice Leplongeon, A

Terminal Pleistocene lithic variability in the Western Negev (Israel): Is there any evidence for contacts with the Nile Valley? Alice Leplongeon, A. Nigel Goring-Morris To cite this version: Alice Leplongeon, A. Nigel Goring-Morris. Terminal Pleistocene lithic variability in the Western Negev (Israel): Is there any evidence for contacts with the Nile Valley?. Journal of lithic studies, University of Edinburgh, 2018, 5 (5 (1)), pp.xx - xx. 10.2218/jls.2614. hal-02268286 HAL Id: hal-02268286 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02268286 Submitted on 20 Aug 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Terminal Pleistocene lithic variability in the Western Negev (Israel): Is there any evidence for contacts with the Nile Valley? Alice Leplongeon 1,2,3, A. Nigel Goring-Morris 3 1. UMR CNRS 7194, Human & Environment Department, Muséum national d’Histoire Naturelle - Université Via Domitia Perpignan - Sorbonne Universités, 1 rue René Panhard, 75013 Paris, France. Email: [email protected] 2. McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, CB2 3ER Cambridge, U.K. 3. Institute of Archaeology, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem 91905, Israel. -

Pdf (334.27 K)

CATRINA (2013), 8 (1): 21 - 28 © 2013 BY THE EGYPTIAN SOCIETY FOR ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES Pollen Grains Indicators to Plant Habitat Conditions at Some Arid Regions Sadat Area Egypt Ashraf A. Salman. 1* and Mohamed. F. Azzazy 2 1 Botany Department, Faculty of Science, Port Said University, Port Said, Egypt 2 Natural Survey Resource Department, Environmental Studies and Research Institute, Minufiya University, Egypt ABSTRACT Nine profiles were studied at Sadat desert area. Xerophytes growing during rainy season represent the common plant cover. The studied soil samples revealed that soils contain high alkalinity, and sandy texture. Palenological studies of the present and the past vegetation (in soil profile strata) revealed the presence of pollen of seventeen families, twelve belonging to present cover ( Poaceae, Typhaceae, Tamaricaceae, Cyperaceae, Chenopodiaceae, Fabaceae, Apiaceae, Lamiaceae, Cruciferae, Plantaginacea, Convolvulaceae and Asteraceae) of present day, while five families recorded at the deep layers of the profiles not represented in the surface layers (Juncaceae, Caryophyllaceae, Oleaceae, Cucrbitaceae, and Geraniaceae). Also eleven families were repre- sented in the lower layers and uppermost ones. Ecological changes took place in the uppermost layer of the profile, changing into desert habitat. This may be due to climatic changes and man interference. Key words: Arid habitats, Climate change, Palynology, Sadat area Egypt, Xerophytes pollen. INTRODUCTION MATERIALS AND METHODS The value of pollen grains as a tool for reconstruction of the past vegetation and environment, and its Study Area applications in archaeology, geology, honey analysis, Sadat City was established in 1976: to become a new archaeobotany and forensic science is now widely known residential based on industrial and agricultural activities, (Moore et al., 1992). -

An Attack by a Warthog, Phacochoerus Africanus, on a Newborn Thomson's Gazelle, Gazella Thomsonii

An attack by a warthog, Phacochoerus africanus, on a newborn Thomson’s gazelle, Gazella thomsonii Blair A. Roberts Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Princeton University Princeton, NJ 08540, USA Accepted 27 April, 2012 Introduction PM. Twenty-four minutes later, while the fawn was standing unsteadily after suckling and This note reports a previously undescribed after the mother had consumed all visible birth behaviour of an attack by a warthog (Phacochoe- materials from the neonate and the birth site, rus africanus) on a newborn Thomson’s gazelle an adult male warthog approached the pair. (Gazella thomsonii). Most instances of interspe- When it came within several metres of the cific aggression in wild animals occur in the gazelles, the mother turned to face it, leaving contexts of predation (Polis, Myers & Holt, the fawn between her and the warthog. The 1989; Kamler et al., 2007) or competition warthog rushed at the fawn, hooked it with its (e.g. Moore, 1978; Berger, 1985; Loveridge & tusk and tossed it approximately 3 m in the air. Macdonald, 2002; Schradin, 2005). However, The warthog then turned to the mother, who warthogs are omnivores that are not known to first lowered her horns but quickly retreated. prey on gazelle and only rarely include animal The warthog approached the fawn, which protein in their diets (Cumming, 1975). Also, had not moved since landing on the ground. the two species typically associate closely with- It sniffed the fawn, nudging it with its snout. out overt signs of aggression and exhibit subtle It then grasped the fawn’s hindquarters in its differences in diet, which minimize competition mouth (Fig. -

Research Article Demographic Analysis of Cornulaca Monacantha Delile Population in Asir Region, Saudi Arabia

Egypt. J. Exp. Biol. (Bot.), 7(1): 67 – 78 (2011) © The Egyptian Society of Experimental Biology RESEARCH ARTICLE Mohamed A. El-Beheiry Kamal H. Shaltout DEMOGRAPHIC ANALYSIS OF CORNULACA MONACANTHA DELILE POPULATION IN ASIR REGION, SAUDI ARABIA ABSTRACT: The present paper aims to study the INTRODUCTION: demography and growth strategy of Cornulaca The amount of vegetation and the ratio monacantha Delile population under natural and of living to dead plant material in any habitat experimental conditions in Asir region, Saudi at any time point depend upon the balance Arabia (in terms of size structure, natality, obtaining between the processes of mortality, and demographic flux) and to assess production and destruction. Even within one its standing crop and the correlation between its environment, there may be considerable population characters and the prevailing variation in the mechanisms, which bring environmental variables. Thirty permanent about the destruction of vegetation stands were established to represent the components. In addition to natural microvariations in five habitats, where C. catastrophes (e.g. floods and wind storms) monacantha inhabits. In each stand, the height and the drastic forms of human impact (e.g. from the ground and the average diameter of the canopy for each C. monacantha individual were ploughing, moving, trampling, and burning), estimated monthly and its volume was account must be taken for more subtle effects calculated as a cylinder. The results showed such as those due to climatic fluctuations, significant variation in its growth variables in decomposing organisms, pathogens and relation to habitat types. The growth follows a herbivores (Grime, 2002; Morales and Carlo, seasonal pattern, where the highest values for 2006), most growth variables were obtained during The struggle for existence among plants Marsh and April, while the lowest during is, to a large extent, the struggle to grow in October and November. -

La Ricostruzione Dell'immaginario Violato in Tre Scrittrici Italofone Del Corno D'africa

Igiaba Scego La ricostruzione dell’immaginario violato in tre scrittrici italofone del Corno D’Africa Aspetti teorici, pedagogici e percorsi di lettura Università degli Studi Roma Tre Facoltà di Scienze della Formazione Dipartimento di Scienze dell’Educazione Dottorato di ricerca in Pedagogia (Ciclo XX) Docente Tutor Coordinatore della Sezione di Pedagogia Prof. Francesco Susi Prof. Massimiliano Fiorucci Direttrice della Scuola Dottorale in Pedagogia e Servizio Sociale Prof.ssa Carmela Covato Anno Accademico 2007/2008 Per la stella della bandiera Somala e per la mia famiglia Estoy leyendo una novela de Luise Erdrich. A cierta altura, un bisabuelo encuentra a su bisnieto. El bisabuelo está completamente chocho (sus pensamiemto tiene nel color del agua) y sonríe con la misma beatífica sonrisa de su bisnieto recién nacido. El bisabuelo es feliz porque ha perdido la memoria que tenía. El bisnieto es feliz porque no tiene, todavía, ninguna memoria. He aquí, pienso, la felicidad perfecta. Yo no la quiero Eduardo Galeano Parte Prima Subire l’immaginario. Ricostruire l’immaginario. Il fenomeno e le problematiche Introduzione Molte persone in Italia sono persuase, in assoluta buona fede, della positività dell’operato italiano in Africa. Italiani brava gente dunque. Italiani costruttori di ponti, strade, infrastrutture, palazzi. Italiani civilizzatori. Italiani edificatori di pace, benessere, modernità. Ma questa visione delineata corrisponde alla realtà dei fatti? Gli italiani sono stati davvero brava gente in Africa? Nella dichiarazioni spesso vengono anche azzardati parallelismi paradossali tra la situazione attuale e quella passata delle ex colonie italiane. Si ribadisce con una certa veemenza che Libia, Etiopia, Somalia ed Eritrea tutto sommato stavano meglio quando stavano peggio, cioè dominati e colonizzati dagli italiani. -

Scf Pan Sahara Wildlife Survey

SCF PAN SAHARA WILDLIFE SURVEY PSWS Technical Report 12 SUMMARY OF RESULTS AND ACHIEVEMENTS OF THE PILOT PHASE OF THE PAN SAHARA WILDLIFE SURVEY 2009-2012 November 2012 Dr Tim Wacher & Mr John Newby REPORT TITLE Wacher, T. & Newby, J. 2012. Summary of results and achievements of the Pilot Phase of the Pan Sahara Wildlife Survey 2009-2012. SCF PSWS Technical Report 12. Sahara Conservation Fund. ii + 26 pp. + Annexes. AUTHORS Dr Tim Wacher (SCF/Pan Sahara Wildlife Survey & Zoological Society of London) Mr John Newby (Sahara Conservation Fund) COVER PICTURE New-born dorcas gazelle in the Ouadi Rimé-Ouadi Achim Game Reserve, Chad. Photo credit: Tim Wacher/ZSL. SPONSORS AND PARTNERS Funding and support for the work described in this report was provided by: • His Highness Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi • Emirates Center for Wildlife Propagation (ECWP) • International Fund for Houbara Conservation (IFHC) • Sahara Conservation Fund (SCF) • Zoological Society of London (ZSL) • Ministère de l’Environnement et de la Lutte Contre la Désertification (Niger) • Ministère de l’Environnement et des Ressources Halieutiques (Chad) • Direction de la Chasse, Faune et Aires Protégées (Niger) • Direction des Parcs Nationaux, Réserves de Faune et de la Chasse (Chad) • Direction Générale des Forêts (Tunis) • Projet Antilopes Sahélo-Sahariennes (Niger) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Sahara Conservation Fund sincerely thanks HH Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi, for his interest and generosity in funding the Pan Sahara Wildlife Survey through the Emirates Centre for Wildlife Propagation (ECWP) and the International Fund for Houbara Conservation (IFHC). This project is carried out in association with the Zoological Society of London (ZSL). -

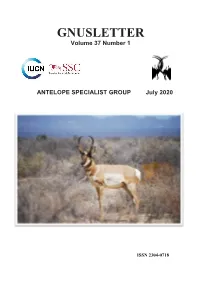

GNUSLETTER Volume 37 Number 1

GNUSLETTER Volume 37 Number 1 ANTELOPE SPECIALIST GROUP July 2020 ISSN 2304-0718 IUCN Species Survival Commission Antelope Specialist Group GNUSLETTER is the biannual newsletter of the IUCN Species Survival Commission Antelope Specialist Group (ASG). First published in 1982 by first ASG Chair Richard D. Estes, the intent of GNUSLETTER, then and today, is the dissemination of reports and information regarding antelopes and their conservation. ASG Members are an important network of individuals and experts working across disciplines throughout Africa and Asia. Contributions (original articles, field notes, other material relevant to antelope biology, ecology, and conservation) are welcomed and should be sent to the editor. Today GNUSLETTER is published in English in electronic form and distributed widely to members and non-members, and to the IUCN SSC global conservation network. To be added to the distribution list please contact [email protected]. GNUSLETTER Review Board Editor, Steve Shurter, [email protected] Co-Chair, David Mallon Co-Chair, Philippe Chardonnet ASG Program Office, Tania Gilbert, Phil Riordan GNUSLETTER Editorial Assistant, Stephanie Rutan GNUSLETTER is published and supported by White Oak Conservation The Antelope Specialist Group Program Office is hosted and supported by Marwell Zoo http://www.whiteoakwildlife.org/ https://www.marwell.org.uk The designation of geographical entities in this report does not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of IUCN, the Species Survival Commission, or the Antelope Specialist Group concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area, or concerning the delimitation of any frontiers or boundaries. Views expressed in Gnusletter are those of the individual authors, Cover photo: Peninsular pronghorn male, El Vizcaino Biosphere Reserve (© J. -

The Human Conveyor Belt : Trends in Human Trafficking and Smuggling in Post-Revolution Libya

The Human Conveyor Belt : trends in human trafficking and smuggling in post-revolution Libya March 2017 A NETWORK TO COUNTER NETWORKS The Human Conveyor Belt : trends in human trafficking and smuggling in post-revolution Libya Mark Micallef March 2017 Cover image: © Robert Young Pelton © 2017 Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Global Initiative. Please direct inquiries to: The Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime WMO Building, 2nd Floor 7bis, Avenue de la Paix CH-1211 Geneva 1 Switzerland www.GlobalInitiative.net Acknowledgments This report was authored by Mark Micallef for the Global Initiative, edited by Tuesday Reitano and Laura Adal. Graphics and layout were prepared by Sharon Wilson at Emerge Creative. Editorial support was provided by Iris Oustinoff. Both the monitoring and the fieldwork supporting this document would not have been possible without a group of Libyan collaborators who we cannot name for their security, but to whom we would like to offer the most profound thanks. The author is also thankful for comments and feedback from MENA researcher Jalal Harchaoui. The research for this report was carried out in collaboration with Migrant Report and made possible with funding provided by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Norway, and benefitted from synergies with projects undertaken by the Global Initiative in partnership with the Institute for Security Studies and the Hanns Seidel Foundation, the United Nations University, and the UK Department for International Development. About the Author Mark Micallef is an investigative journalist and researcher specialised on human smuggling and trafficking. -

Document De Reference

14APR201007404224 Societ´ e´ anonyme a` conseil de surveillance et directoire Au capital social de 10 254 060 euros Siege` social : 18, rue Troyon 92 316 Sevres` 552 056 152 R.C.S. Nanterre DOCUMENT DE REFERENCE VALANT RAPPORT FINANCIER ANNUEL 18MAY200511402118 En application de son Reglement` gen´ eral´ et notamment de l’article 212-13, l’Autorite´ des marches´ financiers a enregistre´ le present´ document de ref´ erence´ le 13 avril 2010 sous le numero´ R.10-020. Ce document ne peut etreˆ utilise´ a` l’appui d’une operation´ financiere` que s’il est complet´ e´ par une note d’operation´ visee´ par l’Autorite´ des marches´ financiers. Il a et´ e´ etabli´ par l’emetteur´ et engage la responsabilite´ de ses signataires. L’enregistrement, conformement´ aux dispositions de l’article L.621-8-1-I du code monetaire´ et financier, a et´ e´ effectue´ apres` que l’AMF a verifi´ e´ « si le document est complet et comprehensible,´ et si les informations qu’il contient sont coherentes´ ». Il n’implique pas l’authentification par l’AMF des el´ ements´ comptables et financiers present´ es.´ Des exemplaires du present´ document de ref´ erence´ sont disponibles sans frais au siege` social de CFAO, 18, rue Troyon, 92316 Sevres` – France. Le document de ref´ erence´ peut egalement´ etreˆ consulte´ sur les sites internet de CFAO (www.cfaogroup.com) et de l’Autorite´ des marches´ financiers (www.amf-france.org). REMARQUES GENERALES Le present´ document de ref´ erence´ est egalement´ constitutif : • du rapport financier annuel devant etreˆ etabli´ et publie´ par toute societ´ e´ cotee´ dans les quatre mois de la clotureˆ de chaque exercice, conformement´ a` l’article L.451-1-2 du Code monetaire´ et financier et a` l’article 222-3 du Reglement` gen´ eral´ de l’AMF, et • du rapport de gestion annuel du Directoire de la Societ´ e´ devant etreˆ present´ e´ a` l’assemblee´ gen´ erale´ des actionnaires approuvant les comptes de chaque exercice clos, conformement´ aux articles L.225-100 et suivants du Code de commerce.