1 DEMOGRAPHIC INEQUALITIES and IMPLICATIONS for POLITICAL REPRESENTATION in INDIA J. RETNAKUMAR Abstract the Pattern of Represe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rotary Invitation

ROTARY INTERNATIONAL Rotary International is a service organisation with over 34,301 clubs, in more than 209 countries, approximately 12,23,413 members and in India 3,141 Rotary clubs, with more than 1,18,895 members undertake humanitarian programs that address today’s challenging issues CORE ESSENCE A worldwide network of inspired individuals who translate their passions into relevant social causes to change lives in communities. MISSION We provide service to others, promote integrity, and advance world understanding, goodwill, and peace through our fellowship of business, professional, and community leaders. Rotary International District 3150 encompasses 2 Revenue Districts Guntur and Prakasam in the State of Andhra Pradesh and 10 Revenue Districts in the State of Telangana including Twin Cities. The Clubs in 3150 are involved in providing safe drinking water in villages and schools conducting health camps and eye camps providing sewing machines and buffallows to the under priveleged women. The clubs are also actively involved in providing Reverse Osmosis Plants & Dual Desks in Schools. Over the last Five Years we have provided more than 75,000 school desks with the support of our International Partners. ROTARIANS PLEDGE TO ERADICATE ILLITERACY FROM INDIA Rotary International’s successful “End T - Teacher Support Thus, the “T-E-A-C-H Program” includes FIVE Polio” Program that resulted in eradication “Projects”, each with specific focus of Polio, totally from India and from nearly E - E-Learning but inter-linked with the others in objective and 99% of the world, has motivated the A - Adult Literacy content so as to contribute to the Rotarians in South Asia to adopt “Rotary’s program goal of Total Literacy accompanied Total Literacy Mission” in India, the Rotary C - Child Development with improvement in learning outcome of India Literacy Mission wishes to achieve primary / elementary education and spread of the Literacy goals through its T-E-A-C-H H - Happy Schools adult literacy in various parts of the Program: Country. -

School Dropouts Or Pushouts? Overcoming Barriers for the Right to Education

Consortium for Research on Educational Access, Transitions and Equity School Dropouts or Pushouts? Overcoming Barriers for the Right to Education Anugula N. Reddy Shantha Sinha CREATE PATHWAYS TO ACCESS Research Monograph No. 40 July 2010 National University of Educational Planning and Administration NUEPA The Consortium for Educational Access, Transitions and Equity (CREATE) is a Research Programme Consortium supported by the UK Department for International Development (DFID). Its purpose is to undertake research designed to improve access to basic education in developing countries. It seeks to achieve this through generating new knowledge and encouraging its application through effective communication and dissemination to national and international development agencies, national governments, education and development professionals, non-government organisations and other interested stakeholders. Access to basic education lies at the heart of development. Lack of educational access, and securely acquired knowledge and skill, is both a part of the definition of poverty, and a means for its diminution. Sustained access to meaningful learning that has value is critical to long term improvements in productivity, the reduction of inter-generational cycles of poverty, demographic transition, preventive health care, the empowerment of women, and reductions in inequality. The CREATE partners CREATE is developing its research collaboratively with partners in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. The lead partner of CREATE is the Centre for International -

List Police Station Under the District (Comma Separated) Printable District

Passport District Name DPHQ Name List of Pincode Under the District (Comma Separated) List Police Station Under the District (comma Separated) Printable District Saifabad, Ramgopalpet, Nampally, Abids , Begum Bazar , Narayanaguda, Chikkadpally, Musheerabad , Gandhi Nagar , Market, Marredpally, 500001, 500002, 500003, 500004, 500005, 500006, 500007, 500008, Trimulghery, Bollarum, Mahankali, Gopalapuram, Lallaguda, Chilkalguda, 500012, 500013, 500015, 500016, 500017, 500018, 500020, 500022, Bowenpally, Karkhana, Begumpet, Tukaramgate, Sulthan Bazar, 500023, 500024, 500025, 500026, 500027, 500028, 500029, 500030, Afzalgunj, Chaderghat, Malakpet, Saidabad, Amberpet, Kachiguda, 500031, 500033, 500034, 500035, 500036, 500038, 500039, 500040, Nallakunta, Osmania University, Golconda, Langarhouse, Asifnagar, Hyderabad Commissioner of Police, Hyderabad 500041, 500044, 500045, 500048, 500051, 500052, 500053, 500057, Hyderabad Tappachabutra, Habeebnagar, Kulsumpura, Mangalhat, Shahinayathgunj, 500058, 500059, 500060, 500061, 500062, 500063, 500064, 500065, Humayun Nagar, Panjagutta, Jubilee Hills, SR Nagar, Banjarahills, 500066, 500067, 500068, 500069, 500070, 500071, 500073, 500074, Charminar , Hussainialam, Kamatipura, Kalapather, Bahadurpura, 500076, 500077, 500079, 500080, 500082, 500085 ,500081, 500095, Chandrayangutta, Chatrinaka, Shalibanda, Falaknuma, Dabeerpura, 500011, 500096, 500009 Mirchowk, Reinbazar, Moghalpura, Santoshnagar, Madannapet , Bhavaninagar, Kanchanbagh 500005, 500008, 500018, 500019, 500030, 500032, 500033, 500046, Madhapur, -

Annual Report 2012-13

Dr. YSRHU Annual Report 2012-13 1 Dr. YSRHU Annual Report 2012-13 Dr.YSRHU, Annual Report, 2012-13 Published by Dr.YSR Horticultural University Administrative Office, P.O. Box No. 7, Venkataramannagudem-534 101, W.G. Dist., A.P. Phones : 08818-284312, Fax : 08818-284223 E-mail : [email protected], [email protected] URL : www.drysrhu.edu.in Compiled and Edited by Dr. B. Srinivasulu, Registrar & Director of Research (FAC), Dr.YSRHU Dr.M.B.Nageswararao, Director of Extension, Dr.YSRHU Dr.M.Lakshminarayana Reddy, Dean of Horticulture, Dr.YSRHU Dr.D.Srihari, Dean of Student Affairs & Dean PG Studies, Dr.YSRHU Dr.M.Pratap, Controller of Examinations, Dr.YSRHU All rights are reserved. No part of this book shall be reproduced or transmitted in any form by print, microfilm or any other means without written permission of the Vice-Chancellor, Dr.Y.S.R. Horticultural University, Venkataramannagudem. Printed at New Image Graphics, Vijayawada-2, Ph : 0866 2435553 2 Dr. YSRHU Annual Report 2012-13 Dr.B.M.C.REDDY VICE-CHANCELLOR Dr.Y.S.R. Horticultural University I am happy to present the Fifth Annual Report of Dr.Y.S.R. Horticultural University (Dr.YSRHU). It is a compiled document of the University activities during the year 2012-13. Dr.YSR Horticultural University was established at Venkataramannagudem, West Godavari District, Andhra Pradesh on 26th June, 2007. Dr.YSR Horticultural University is second of its kind in the country, with the mandate for Education, Research and Extension related to horticulture and allied subjects. The university at present has 4 Horticultural Colleges, 5 Polytechnics, 27 Research Stations and 3 KVKs located in 9 agro-climatic zones of the state. -

Agrometeorological Data Collection, Analysis and Management

Agrometeorological Data Collection, Analysis and Management ICAR Sponsored Training Program for Technical Officers 25th July to 6th August 2016 Lecture Notes Editors P Vijayakumar, AVM Subba Rao and MA Sarath Chandran All India Coordinated Research Project on Agrometeorology ICAR-Central Research Institute for Dryland Agriculture Santoshnagar, Hyderabad – 500 059 Citation: Vijayakumar P, Subba Rao AVM and Sarath Chandran MA. 2016. Agrometeorological Data Collection, Analysis and Management. Central Research Institute for Dryland Agriculture, Hyderabad- 500 059. 152p. Editors P Vijayakumar AVM Subba Rao MA Sarath Chandran Agrometeorological Data Collection, Analysis and Management ICAR Sponsored training program for technical officers 25th July to 6th August 2016 CONTENTS Lecture Topic Speaker Page Basic Concepts of Agrometeorology B.V. Ramana Rao 1 Monsoon: Concept and its Features VUM Rao 7 Measurement of Solar Radiation BV Ramana Rao 15 The importance of monitoring weather parameters in GGSN Rao 18 crop insurance schemes Agroclimatic indices and their application P Vijaya Kumar 26 Crop -Weather Relationships P Vijayakumar 40 Crop Water Requirements AVM Subba Rao and MA 51 Sarath Chandran Agroclimatic Database Management System AVR Kesava Rao and 62 Suhas P Wani Statistical Analysis of Agromet Data including BMK Raju 68 Rainfall Probability Weather elements influencing plant disease Suseelendra Desai 85 Micro-level Agromet Advisory Services H Venkatesh 92 Water Balance by Thornthwaite & Mather And FAO GGSN Rao 97 Methods Computations -

AIMS Founder Members

AIMS Founder Members FM1 Prof J Philip Chairman Xavier Institute of Management & Entrepreneurship Electronics City Phase – II Hosur Road, Bangalore 561 229 Tel:080-28528597/98. Email: [email protected] FM2 Prof D Panduranga Rao Academic Advisor SITAM 1-9-8-1/1, Beside State Bank of Hyderabad Ramnagar, VST Cross Road Hyderabad 500 028 Cell: 8808813737 Email: [email protected] FM3 Prof M T Thiagarajan Formerly of Pondicherry University C/o PSG Institute of Management P B No. 1668, Avinashi Road Peelamedu Coimbatore – 641004 Email: [email protected] FM4 Dr G P Rao A 5, 402, Singapore township (Sanskriti Township) Beyond Uppal, Ranga Reddy District Hyderabad-500 038 Email: [email protected] North Zone Valid Members: DL005 Dr Gaganjit Singh Executive President AIMS/LF/DL/NZ/2005 Delhi Chapter (Incl Himachal Pradesh Institute of Marketing & Management and Jammu & Kashmir) Marketing Tower, B - 11 Tara Crescent, Qutab Institutional Area DL001 Dr Alok Saklani New Delhi - 110016 Director Tel: 011-26520892-96 AIMS/LF/DL/NZ/2001 26967596/2226/7541 Apeejay School of Management 26529713 Sector - 8 Email: [email protected] Dwaraka Institutional Area [email protected] New Delhi - 110077 Tel: 011-25363979/80/83/86/88, 25364523 DL006 Dr (Cdr) Satish Seth Email: [email protected] Director General [email protected] AIMS/LF/DL/NZ/2007 Jagannath International Management DL002 Dr Jitendra K Das School Director MOR, Pocket 105, Kalkaji AIMS/LF/DL/NZ/2002 New Delhi - 110019 FORE School of Management Tel: 011-40619200 (100 lines) -

THE ANDHRA PRADESH GAZETTE PUBLISHED by AUTHORITY No

Registered No. HSE–49/2009-2011. [Price: Rs. 1-75 Paise. THE ANDHRA PRADESH GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 16 ] HYDERABAD, THURSDAY, APRIL 21, 2011. Part-I Notifications by Government, Heads of Departments and other Officers –––x––– CONTENTS –––x––– NOTIFICATIONS BY GOVERNMENT Pages Pages MINORITIES WELFARE DEPART- REVENUE DEPARTMENT MENT (Endts.-II) (Wakf - I) NOTIFICATION: Appointments .. 251-252 Sri Sangameshwara Swamy Temple Gandhi MUNICIPAL ADMINISTRATION Nagar New Bakaram, Secunderabad AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT Exempted from the operation of Sections 15 DEPARTMENT and 29 of the Andhra Pradesh Chairtable and Hindu Religious Institutions and Endowments (H - 1) Act, 30/1987. .. 253 NOTIFICATION: TRANSPORT, ROADS & BUILDINGS Variation to the Master Plan of the Nellore DEPARTMENT Municipal Corporation. .. 252-253 (Tr. I) NOTIFICATION: Exemption of Motor Vehicles Tax in respect of vehicle bearing No. AP-09-Y-9978 belongs to Vimochana, Andhra Pradesh Unit of Person Ministry of India, Hyderabad .. 253 NOTIFICATIONS BY HEADS OF DEPARTMENTS, ETC. Additional Commissioner (CT), Office of Commissioner of Commercial Taxes, A.P., Hyderabad .. 253-262 [P-I-(i)] P-I/21-04-2011/1 NOTIFICATIONS BY GOVERNMENT MINORITIES WELFARE DEPARTMENT Prakasam District for performing of Marriages of (Wakf-I) Muslims. APPOINTMENT OF SRI SHAIK NAYAB RASOOL, APPOINTMENT OF SRI MULLAH CHAND BASHA S/o SHAIK MOULA ALI AS GOVT. KHAZI TO S/o LATE NAYAB RASOOL AS GOVT. KHAZI GIDDALUR TOWN, PRAKASAM DISTRICT FOR FOR PODILI, MARRIPUDI AND KONAKANA- PERFORMING MARRIAGES OF MUSLIMS. METLA MANDALS OF PRAKASAM DISTRICT FOR PERFORMING MARRIAGES OF MUSLIMS. [G .O.Ms.No. 91, Minorities Welfare (Wakf-I), [G .O.Ms.No. 94, Minorities Welfare (Wakf-I), 15th March, 2011]. -

Details of Staff Working at Dist. / Constituency / Mandal Level As on 27-07-2019

GOVERNMENT OF TELANGANA DEPARTMENT OF HORTICULTURE & SERICULTURE Details of Staff Working at Dist. / Constituency / Mandal Level as on 27-07-2019 INDEX Page Numbers Page Numbers S.No District Name S.No District Name From -- To From -- To 1 Adilabad 1 to 2 17 Mahabubnagar 29 to 30 2 Nirmal 3 to 4 18 Narayanapet 31 3 Mancherial 5 to 6 19 Nagarkurnool 32 to 33 4 Komarambheem 7 20 Gadwal 34 to 35 5 Karimnagar 8 to 9 21 Wanaparthy 36 to 37 6 Peddapalli 10 22 Vikarabad 38 to 39 7 Jagityal 11 to 12 23 Rangareddy 40 to 41 8 Siricilla 13 24 Medchal 42 9 Warangal ( R) 14 to 15 25 Sangareddy 43 to 44 10 Warangal(U) 16 to 17 26 Medak 45 to 46 11 Bhupalapally 18 to 19 27 Siddipiet 47 to 48 12 Mulugu 20 28 Nizamabad 49 to 50 13 Mahbubabad 21 to 22 29 Kamareddy 51 to 52 14 Jangaon 23 to 24 30 Nalgonda 53 to 55 15 Khammam 25 to 26 31 Suryapet 56 to 57 16 Kothagudem 27 to 28 32 Yadadri 58 to 59 Statement showing the Officer & Staff working in Horticulture & Sericulture Department No. of Assembly Constituencies : 2 Adilabad Constituency = 5 mandals Boath Constituency = 9 mandals Name of the new District:- No. of Mandals : 18 ADILABAD Part of Khanapur Constituency = 2 mandals Part of Asifabad constituency = 2 mandals Total mandals = 18 Sl. Name of the Employee Head Quarters / Assembly No. of Name of the Designation Name of the Mandals (Jurisdiction) No. Sarvasri/ Smt./ Kum. Constituency Mandals MLH&SO A - District Level Horticulture & Sericulture Officer Mulug, Venkatapur, Govindaraopet, K.Venkateshwarlu PD/ DH&SO, Adilabad 1 Adilabad Tadvai, Eturnagaram, Mangapet, 7997724995 (DDO - Adilabad ) Kannaigudem, Wajedu, Venkatapuram B - Constituency Level Officers Adilabad 1 Adilabad (R), Ch.Pranay Reddy MLH&SO(MIP) G.Srinivas Boath 1 Bheempur 7997725008 1 HO(T)/ CLH&SO 7997725002 A. -

Labor Versus Learning : Explaining the State-Wise

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Political Science Political Science 2014 LABOR VERSUS LEARNING: EXPLAINING THE STATE-WISE VARIATION OF CHILD LABOR IN INDIA Priyam Saharia University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Saharia, Priyam, "LABOR VERSUS LEARNING: EXPLAINING THE STATE-WISE VARIATION OF CHILD LABOR IN INDIA" (2014). Theses and Dissertations--Political Science. 10. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/polysci_etds/10 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Political Science at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Political Science by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

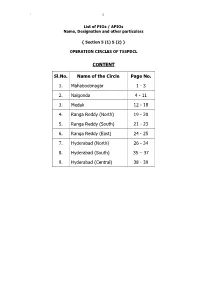

Name, Designation and Other Particulars of Public Information Officers

` 0 List of PIOs / APIOs Name, Designation and other particulars { Section 5 (1) 5 (2) } OPERATION CIRCLES OF TSSPDCL CONTENT Sl.No. Name of the Circle Page No. 1. Mahaboobnagar 1 - 3 2. Nalgonda 4 - 11 3. Medak 12 - 18 4. Ranga Reddy (North) 19 - 20 5. Ranga Reddy (South) 21 - 23 6. Ranga Reddy (East) 24 - 25 7. Hyderabad (North) 26 - 34 8. Hyderabad (South) 35 – 37 9. Hyderabad (Central) 38 - 39 ` 1 Name, Designation and other Particulars of Public Information Officers { Section 5 (1) 5 (2) } Mahaboobnagar Circle Sl. Name of the office Name of the PIO and Cell No. Name of the APIO and Cell No. No. District office Circle / Sri N.S.R.Murthy, DE/Technical,,Cell:9440813415, Sri B. Manikyalu, ADE/Tech., 1 Mahaboobnagar 08542-272946-272714,Fax 08542 - 272798 ,cell:9440813415, 08542-272730 G.Sudha Rani AE/Tech/D.O./MBNR,, 2 Division /Mahaboobnagar Venkataiah, DE/OP/MAHABUBNAGAR,, 9440813418 08542-273138 Sub-division, Sureshkumar, Sub-Er/MBNR(TOW),, 3 Srinivasa Chary, ADE/OP/MBNR(TOWN).,, 9440813431 Mahaboobnagar 08503-272926 Shanthi , Sub-Er./OP/TOWN-1, 4 Section Town-I/MBNR B.Ramesh Babu, AE/OP/TOWN-1,, 9440813457 08542-241666 Vacant, Sub-Er./OP/TOWN-2, 5 Section Town-II/MBNR Satyanna, AE/OP/TOWN-2,, 9491066205 08542-243666 6 Section /Town-III/MBNR M.Srinivas, AE/OP/TOWN-3,, 9440813459 K.Venkatesh/ Town-3,, 08542-243555 Ramakrishna, Sub-Er/MBNR(RURAL),, 7 Sub-division,MBNR Rural B.Srinivasulu, ADE/OP/MBNR(RURAL),, 9440813444 08542-273146 Chandra Shekar sub-eng I/C AE/OP/C&O/MBNR,, Chandra shekar sub-Er (I/C), 8 C&O/Section/MBNR 9440813890 Sub-Engineer, 9 Section/Koilkonda B. -

Aurobindo AR 2017 Final

ANNUAL REPORT 2016-17 Aurobindo Pharma Limited | Annual Report 2016-17 Limited | Annual Pharma Aurobindo Investing in reliability www.aurobindo.com REGISTERED OFFICE CORPORATE OFFICE AUROBINDO PHARMA LIMITED PLOT NO. 2, MAITRI VIHAR WATER MARK BUILDING AMEERPET PLOT NO. 11, SURVEY NO. 9 HYDERABAD - 500 038 KONDAPUR, HITECH CITY TELANGANA, INDIA HYDERABAD - 500 084 TELANGANA, INDIA Auro Mission Aurobindo's mission is to become the most valued pharmaceutical partner to the world pharma fraternity by continuously researching, developing and manufacturing a wide range of pharmaceutical products that comply with the highest regulatory standards. Auro Values BUSINESS CARE PEOPLE CARE ORGANIZATION CARE Operational excellence Fairness, humility and Accountability respect for individuals Stakeholder orientation Integrity Teamwork Quality Achievement Applied learning Forward Looking Statements This communication contains statements that constitute ‘forward looking statements’ including, without limitation, statements relating to the implementation of strategic initiatives and other statements relating to our future business developments and economic performance. While these forward looking statements represent our judgements and future expectations concerning the development of our business, a number of risks, uncertainties and other important factors could cause actual developments and results to differ materially from our expectations. These factors include, but are not limited to, general market, macro-economic, governmental and regulatory trends, movements in currency exchange and interest rates, competitive pressures, technological developments, changes in the financial conditions of third parties dealing with us, legislative developments, and other key factors that we have indicated could adversely affect our business and financial performance. Aurobindo undertakes no obligation to publicly revise any forward looking statements to reflect future events or circumstances. -

State District Branch Address Centre Ifsc

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR_CODE A.N.REDDY NAGAR ANDHRA A N REDDY BR,NIRMAL,ANDHRA PRADESH ADILABAD NAGAR PRADESH NIRMAL ANDB0001972 8734243159 NONMICR 3-2-29/18D, 1ST CH.NAGAB FLOOR, AMBEDKAR HUSHANA ANDHRA CHOWK ADILABAD - M 08732- PRADESH ADILABAD ADILABAD 504 001 ADILABAD ANDB0000022 230766 TARA COMPLEX,MAIN ANDHRA ROAD,ASIFABAD,ADI 08733 PRADESH ADILABAD ASIFABAD LABAD DT - 504293 ASIFABAD ANDB0002010 279211 504011293 TEMPLE STREET, BASARA ADILABAD, ANDHRA ADILABAD, ANDHRA 986613998 PRADESH ADILABAD BASARA PRADESH-504104 BASAR ANDB0001485 1 Bazar Area, Bellampally , Adilabad G.Jeevan Reddy ANDHRA Dist - - 08735- PRADESH ADILABAD Bellampalli Bellampalli ADILABAD ANDB0000068 504251 2222115 ANDHRA BANK, BHAINSA BASAR P.SATYAN ROAD BHAINSA- ARAYANA - ANDHRA 504103 ADILABAD 08752- PRADESH ADILABAD BHAINSA DIST BHAINSA ANDB0000067 231108 D.NO 4-113/3/2,GOVT JUNIOR COLLEGE ROAD,NEAR BUS ANDHRA STAND,BOATH - 949452190 PRADESH ADILABAD BOATH 504305 BOATH ANDB0002091 1 MAIN ROAD,CHENNUR, ADILABAD DIST, ANDHRA CHENNUR, ANDHRA 087372412 PRADESH ADILABAD CHENNUR PRADESH-504201 CHINNOR ANDB0000098 36 9-25/1 BESIDE TANISHA GARDENS, ANDHRA DASNAPUR, PRADESH ADILABAD DASNAPUR ADILABAD - 504001 ADILABAD ANDB0001971 NO NONMICR ORIENT CEMENT WORKS CO, DEVAPUR,ADILABAD DIST, DEVAPUR, ANDHRA ANDHRA PRADESH- 08736 PRADESH ADILABAD DEVAPUR 504218 DEVAPUR ANDB0000135 240531 DOWEDPALLI, LXXETTIPET 08739- ANDHRA VILLAGE, GANDHI DOWDEPAL 233666/238 PRADESH ADILABAD DOWDEPALLI CHOWK LI ANDB0000767 222 H NO 1-171 VILL