Labor Versus Learning : Explaining the State-Wise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tribal Handicraft Report

STATUS STUDY OF TRIBAL HANDICRAFT- AN OPTION FOR LIVELIHOOD OF TRIBAL COMMUNITY IN THE STATES OF ARUNACHAL PRADESH RAJASTHAN, UTTARANCHAL AND CHHATTISGARH Sponsored by: Planning Commission Government of India Yojana Bhawan, Sansad Marg New Delhi 110 001 Socio-Economic and Educational Development Society (SEEDS) RZF – 754/29 Raj Nagar II, Palam Colony. New Delhi 110045 Socio Economic and Educational Planning Commission Development Society (SEEDS) Government of India Planning Commission Government of India Yojana Bhawan, Sansad Marg New Delhi 110 001 STATUS STUDY OF TRIBAL HANDICRAFTS- AN OPTION FOR LIVELIHOOD OF TRIBAL COMMUNITY IN THE STATES OF RAJASTHAN, UTTARANCHAL, CHHATTISGARH AND ARUNACHAL PRADESH May 2006 Socio - Economic and Educational Development Society (SEEDS) RZF- 754/ 29, Rajnagar- II Palam Colony, New Delhi- 110 045 (INDIA) Phone : +91-11- 25030685, 25362841 Email : [email protected] Socio Economic and Educational Planning Commission Development Society (SEEDS) Government of India List of Contents Page CHAPTERS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY S-1 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Objective of the Study 2 1.2 Scope of Work 2 1.3 Approach and Methodology 3 1.4 Coverage and Sample Frame 6 1.5 Limitations 7 2 TRIBAL HANDICRAFT SECTOR: AN OVERVIEW 8 2.1 Indian Handicraft 8 2.2 Classification of Handicraft 9 2.3 Designing in Handicraft 9 2.4 Tribes of India 10 2.5 Tribal Handicraft as Livelihood option 11 2.6 Government Initiatives 13 2.7 Institutions involved for promotion of Handicrafts 16 3 PEOPLE AND HANDICRAFT IN STUDY AREA 23 3.1 Arunachal Pradesh 23 -

Rotary Invitation

ROTARY INTERNATIONAL Rotary International is a service organisation with over 34,301 clubs, in more than 209 countries, approximately 12,23,413 members and in India 3,141 Rotary clubs, with more than 1,18,895 members undertake humanitarian programs that address today’s challenging issues CORE ESSENCE A worldwide network of inspired individuals who translate their passions into relevant social causes to change lives in communities. MISSION We provide service to others, promote integrity, and advance world understanding, goodwill, and peace through our fellowship of business, professional, and community leaders. Rotary International District 3150 encompasses 2 Revenue Districts Guntur and Prakasam in the State of Andhra Pradesh and 10 Revenue Districts in the State of Telangana including Twin Cities. The Clubs in 3150 are involved in providing safe drinking water in villages and schools conducting health camps and eye camps providing sewing machines and buffallows to the under priveleged women. The clubs are also actively involved in providing Reverse Osmosis Plants & Dual Desks in Schools. Over the last Five Years we have provided more than 75,000 school desks with the support of our International Partners. ROTARIANS PLEDGE TO ERADICATE ILLITERACY FROM INDIA Rotary International’s successful “End T - Teacher Support Thus, the “T-E-A-C-H Program” includes FIVE Polio” Program that resulted in eradication “Projects”, each with specific focus of Polio, totally from India and from nearly E - E-Learning but inter-linked with the others in objective and 99% of the world, has motivated the A - Adult Literacy content so as to contribute to the Rotarians in South Asia to adopt “Rotary’s program goal of Total Literacy accompanied Total Literacy Mission” in India, the Rotary C - Child Development with improvement in learning outcome of India Literacy Mission wishes to achieve primary / elementary education and spread of the Literacy goals through its T-E-A-C-H H - Happy Schools adult literacy in various parts of the Program: Country. -

India Labour Market Update ILO Country Office for India | July 2017

India Labour Market Update ILO Country Office for India | July 2017 Overview India’s economy grew by 8.0 per cent in fiscal year (FY) 2016 other sectors in recent years. Most of the new jobs being (April 2015-March 2016), the fastest pace since 2011-12. created in the formal sector are actually informal because However, in 2016-17 the GDP growth rate slowed down to workers do not have access to employment benefits or 7.1 per cent, mostly on account of deceleration in gross social security. In addition, notable disparities in the labour fixed capital formation. IMF’s latest growth forecast shows force participation rates of men and women persist. that disruptions caused by demonetization is unlikely to affect economic growth over the longer term, and GDP Recent economic trends: Growth falls growth is expected to rebound to 7.2 per cent in 2017-18 and 7.7 per cent in FY 2019. Having seen a strong recovery in recent years, gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate declined in 2016-17. Table 1: Key economic and labour market indicators As per the latest estimates released by the Central Macro 2014-15 2015-16 2016-17 Statistical Office (CSO) on May 31, 2017, the GDP growth i, a Real GDP (% change y-o-y) 7.5 8.0 7.1 rate at constant market prices declined to 7.1 per cent in Investment (% of GDP) 35.7 34.9 33.2 Labour market 2004-05 2009-10 2011-12 2016-17, compared to 8.0 per cent in 2015-16. -

Structural Violence Against Children in South Asia © Unicef Rosa 2018

STRUCTURAL VIOLENCE AGAINST CHILDREN IN SOUTH ASIA © UNICEF ROSA 2018 Cover Photo: Bangladesh, Jamalpur: Children and other community members watching an anti-child marriage drama performed by members of an Adolescent Club. © UNICEF/South Asia 2016/Bronstein The material in this report has been commissioned by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) regional office in South Asia. UNICEF accepts no responsibility for errors. The designations in this work do not imply an opinion on the legal status of any country or territory, or of its authorities, or the delimitation of frontiers. Permission to copy, disseminate or otherwise use information from this publication is granted so long as appropriate acknowledgement is given. The suggested citation is: United Nations Children’s Fund, Structural Violence against Children in South Asia, UNICEF, Kathmandu, 2018. STRUCTURAL VIOLENCE AGAINST CHILDREN IN SOUTH ASIA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS UNICEF would like to acknowledge Parveen from the University of Sheffield, Drs. Taveeshi Gupta with Fiona Samuels Ramya Subrahmanian of Know Violence in for their work in developing this report. The Childhood, and Enakshi Ganguly Thukral report was prepared under the guidance of of HAQ (Centre for Child Rights India). Kendra Gregson with Sheeba Harma of the From UNICEF, staff members representing United Nations Children's Fund Regional the fields of child protection, gender Office in South Asia. and research, provided important inputs informed by specific South Asia country This report benefited from the contribution contexts, programming and current violence of a distinguished reference group: research. In particular, from UNICEF we Susan Bissell of the Global Partnership would like to thank: Ann Rosemary Arnott, to End Violence against Children, Ingrid Roshni Basu, Ramiz Behbudov, Sarah Fitzgerald of United Nations Population Coleman, Shreyasi Jha, Aniruddha Kulkarni, Fund Asia and the Pacific region, Shireen Mary Catherine Maternowska and Eri Jejeebhoy of the Population Council, Ali Mathers Suzuki. -

Wild Life Sanctuaries in INDIA

A M K RESOURCE WORLD GENERAL KNOWLEDGE www.amkresourceinfo.com Wild Life Sanctuaries in INDIA Wildlife Sanctuaries in India are 441 in number. They are a home to hundreds and thousands of various flora and fauna. A wide variety of species thrive in such Wildlife Sanctuaries. With the ever growing cement – jungle, it is of utmost importance to protect and conserve wildlife and give them their own, natural space to survive Wildlife Sanctuaries are established by IUCN category II protected areas. A wildlife sanctuary is a place of refuge where abused, injured, endangered animals live in peace and dignity. Senchal Game Sanctuary. Established in 1915 is the oldest of such sanctuaries in India. Chal Batohi, in Gujarat is the largest Wildlife Sanctuary in India. The conservative measures taken by the Indian Government for the conservation of Tigers was awarded by a 30% rise in the number of tigers in 2015. According to the Red Data Book of International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), there are 47 critically endangered species in India. DO YOU KNOW? Wildlife sanctuaries in India are established by IUCN category II protected areas. India has 537 wildlife sanctuaries referred to as wildlife sanctuaries category IV protected areas. Among these, the 50 tiger reserves are governed by Project Tiger, and are of special significance in the conservation of the tiger. Some wildlife sanctuaries in India are specifically named bird sanctuary, e.g., Keoladeo National Park before attaining National Park status. Many of them being referred as as a particular animal such as Jawai leopard sanctuary in Rajasthan. -

Tobacco Use Disorder and Treatment: New Challenges and Opportunities

University of Massachusetts Medical School eScholarship@UMMS Open Access Articles Open Access Publications by UMMS Authors 2017-09-01 Tobacco use disorder and treatment: new challenges and opportunities Douglas Ziedonis University of California - San Diego Et al. Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Follow this and additional works at: https://escholarship.umassmed.edu/oapubs Part of the Behavior and Behavior Mechanisms Commons, Neuroscience and Neurobiology Commons, and the Substance Abuse and Addiction Commons Repository Citation Ziedonis D, Das S, Larkin C. (2017). Tobacco use disorder and treatment: new challenges and opportunities. Open Access Articles. Retrieved from https://escholarship.umassmed.edu/oapubs/3255 Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. This material is brought to you by eScholarship@UMMS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Articles by an authorized administrator of eScholarship@UMMS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Clinical research Tobacco use disorder and treatment: new challenges and opportunities Douglas Ziedonis, MD, MPH; Smita Das, MD, PhD, MPH; Celine Larkin, PhD Introduction obacco use is the cause of over 5 million deaths perT year globally,1 over twice as many deaths due to al- cohol and illicit drugs combined. If current consump- tion rates continue, tobacco is projected to kill 1 billion people this century, with the majority of deaths occur- ring in low- and middle-income countries,2 although there is good evidence for the effectiveness both of pol- Tobacco use remains a global problem, and options for consumers have increased with the development and mar- keting of e-cigarettes and other new nicotine and tobacco products, such as “heat-not-burn” tobacco and dissolv- able tobacco. -

Th,U,E Izf'k{K.K L= 2015&16 Esa Izkir Gq, Vkwuykbzu Qkweksz

th,u,e izf’k{k.k l= 2015&16 esa izkIr gq, vkWuykbZu QkWeksZ GNM Id Candidate Name /Father's Name Category Remark GNM0000000001 ANITA KUMARI MEENA / Mr.LALU RAM TSPST GNM0000000002 TANAY SONI / Mr.NAVIN SONI OBC GNM0000000003 VINOD DAMOR / Mr.MADSIYA DAMOR TSPST GNM0000000004 CHANDRA SINGH PATAWAT / Mr.JAI SINGH PATAWAT GEN GNM0000000005 MUKESH BOCHALIYA / Mr.DEVA RAM OBC GNM0000000006 SURENDAR KUMAR JEDIYA / Mr.RAMPAL JEDIYA SC GNM0000000007 MEENAKSHI MEGHWAL / Mr.SHANKER LAL MEGHWAL SC GNM0000000008 LATA / Mr.SURESH KUMAR SC GNM0000000009 FARMAN ALI / Mr.HARUN ALI OBC GNM0000000010 NARESH REGAR / Mr.BHERU LAL REGAR SC GNM0000000011 MANESH KUMAR / Mr.RATAN LAL OBC GNM0000000012 ASHUTOSH GOSWAMI / Mr.OM PRAKASH OBC GNM0000000013 DEVESH KRISHNA PANCHOLI / Mr.DAYA KRISHNA PANCHOLI GEN GNM0000000014 OM PRAKASH MEENA / Mr.MATHURA LAL MEENA ST GNM0000000015 DEVI LAL PURBIYA / Mr.SOHAN LAL PURBIYA SBC GNM0000000016 MOHAMMAD RAFIK / Mr.AMIN KHAN OBC GNM0000000017 VIKASH KUMAR MEENA / Mr.MANSINGH MEENA ST Reject GNM0000000018 VED KUMAR JATAV / Mr.RAMJI LAL JATAV SC GNM0000000019 RAKESH KUMAR / Mr.OMA RAM ST GNM0000000020 RAJKUMAR REGAR / Mr.TARACHAND REGAR SC GNM0000000021 KRISHAN KUMAR RATHORE / Mr.RAJENDRA SINGH RATHORE OBC GNM0000000022 VIJAY SONI / Mr.NARAYAN SONI OBC GNM0000000023 MANDEEP KUMAR BAIRWA / Mr.BAL KISHAN BAIRWA SC GNM0000000024 VISHVENDRA KUMAR VERMA / Mr.RAJENDRA KUMAR VERMA SC GNM0000000025 SUNIL PRAJAPAT / Mr.OM PRAKASH PRAJAPAT OBC GNM0000000026 SHIMLA BAIRWA / Mr.GHAN SHYAM BAIRWA SC GNM0000000027 SHASHIKANT DEEGWAL / Mr.MOHAN -

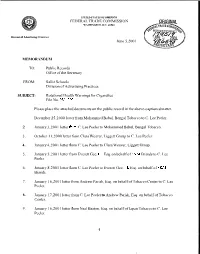

Rotational Health Warnings for Cigarettes File No

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D C. 20580 Division of Advertising Practices June 5,2001 MEMORANDUM TO: Public Records Office of the Secretary FROM: Sallie Schools Division of Advertising Practices SUBJECT: Rotational Health Warnings for Cigarettes File No. Please place the attached documents on the public record in the above-captioned matter. December 25,2000 letter from Mohammed Babul, Bengal Tobacco to C. Lee Peeler. 2. January 3,2001 letter C. Lee Peeler to Mohammed Babul, Bengal Tobacco. 3. October 11,2000 letter fiom Clara Weaver, Liggett Group to C. Lee Peeler. 4. January 4,2001 letter fkom C. Lee Peeler to Clara Weaver, Liggett Group. 5. January 5,2001 letter from Everett Gee, Esq. on behalf of Brands to C. Lee Peeler. 6. January 8,2001 letter fkom C. Lee Peeler to Everett Gee, Esq. on behalf of Brands. 7. January 16,2001 letter from Andrew Parish, Esq. on behalf of Tobacco Center to C. Lee Peeler. 8. January 17,2001 letter from C. Lee Peeler to Andrew Parish, Esq. on behalf of Tobacco Center. 9. January 16,2001 letter fkom Neal Beaton, Esq. on behalf of Japan Tobacco to C. Lee Peeler. 1 Records June 5,2001 Page 2 10. January 19,2001 letter fiom C. Lee Peeler to Neal Beaton, Esq. on behalf of Japan Tobacco. 11. January 10,2001 letter Thomas O’Connell, Sun Tobacco to C. Lee Peeler. 12. January 22,2001 letter from C. Lee Peeler to Thomas O’Connell, Sun Tobacco. 13. January 18,2001 letter fiom Kris Hewitt, Tobacco to C. -

School Dropouts Or Pushouts? Overcoming Barriers for the Right to Education

Consortium for Research on Educational Access, Transitions and Equity School Dropouts or Pushouts? Overcoming Barriers for the Right to Education Anugula N. Reddy Shantha Sinha CREATE PATHWAYS TO ACCESS Research Monograph No. 40 July 2010 National University of Educational Planning and Administration NUEPA The Consortium for Educational Access, Transitions and Equity (CREATE) is a Research Programme Consortium supported by the UK Department for International Development (DFID). Its purpose is to undertake research designed to improve access to basic education in developing countries. It seeks to achieve this through generating new knowledge and encouraging its application through effective communication and dissemination to national and international development agencies, national governments, education and development professionals, non-government organisations and other interested stakeholders. Access to basic education lies at the heart of development. Lack of educational access, and securely acquired knowledge and skill, is both a part of the definition of poverty, and a means for its diminution. Sustained access to meaningful learning that has value is critical to long term improvements in productivity, the reduction of inter-generational cycles of poverty, demographic transition, preventive health care, the empowerment of women, and reductions in inequality. The CREATE partners CREATE is developing its research collaboratively with partners in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. The lead partner of CREATE is the Centre for International -

Tobacco Directory Deletions by Manufacturer

Cigarettes and Tobacco Products Removed From The California Tobacco Directory by Manufacturer Brand Manufacturer Date Comments Removed Catmandu Alternative Brands, Inc. 2/3/2006 Savannah Anderson Tobacco Company, LLC 11/18/2005 Desperado - RYO Bailey Tobacco Corporation 5/4/2007 Peace - RYO Bailey Tobacco Corporation 5/4/2007 Revenge - RYO Bailey Tobacco Corporation 5/4/2007 The Brave Bekenton, S.A. 6/2/2006 Barclay Brown & Williamson * Became RJR July 5/2/2008 2004 Belair Brown & Williamson * Became RJR July 5/2/2008 2004 Private Stock Brown & Williamson * Became RJR July 5/2/2008 2004 Raleigh Brown & Williamson * Became RJR July 5/6/2005 2004 Viceroy Brown & Williamson * Became RJR July 5/3/2010 2004 Coronas Canary Islands Cigar Co. 5/5/2006 Palace Canary Islands Cigar Co. 5/5/2006 Record Canary Islands Cigar Co. 5/5/2006 VL Canary Islands Cigar Co. 5/5/2006 Freemont Caribbean-American Tobacco Corp. 5/2/2008 Kingsboro Carolina Tobacco Company 5/3/2010 Roger Carolina Tobacco Company 5/3/2010 Aura Cheyenne International, LLC 1/5/2018 Cheyenne Cheyenne International, LLC 1/5/2018 Cheyenne - RYO Cheyenne International, LLC 1/5/2018 Decade Cheyenne International, LLC 1/5/2018 Bridgeton CLP, Inc. 5/4/2007 DT Tobacco - RYO CLP, Inc. 7/13/2007 Railroad - RYO CLP, Inc. 5/30/2008 Smokers Palace - RYO CLP, Inc. 7/13/2007 Smokers Select - RYO CLP, Inc. 5/30/2008 Southern Harvest - RYO CLP, Inc. 7/13/2007 Davidoff Commonwealth Brands, Inc. 7/19/2016 Malibu Commonwealth Brands, Inc. 5/31/2017 McClintock - RYO Commonwealth Brands, Inc. -

Migration and Elastic Labour in Economic Development: Southeast Asia Before World War II

Migration and Elastic Labour in Economic Development: Southeast Asia before World War II Gregg Huff Giovanni Caggiano Department of Economics, University of Department of Economics, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8RT Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8RT E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Gregg Huff is reader and Giovanni Caggiano lecturer, Department of Economics, Adam Smith Building, Glasgow G12 8RT, Scotland. Emails: [email protected] and [email protected]. Earlier versions of this article were presented at seminars at All Souls, Oxford, the School of Oriental and African Studies, London and the Universities of Glasgow, Lancaster and Stirling. Thanks to seminar participants for many helpful comments and suggestions and to Bob Allen, Anne Booth, Nicholas Dimsdale, Mike French, Nick Harley, Bob Hart, Jane Humphries, Machiko Nissanke, Campbell Leith, Ramon Meyers, Avner Offer, Catherine Schenk, Nick Snowden, Ken Sokoloff, and Robert Wright. At different times both Jeff Williamson and Jan de Vries suggested the subject of this article as topic worthy of investigation and we are appreciative of their pointers. Thanks also to the editor of this JOURNAL for a number of useful ideas and clarifications which improved the article. We owe a particular debt of gratitude to two anonymous referees and to Ulrich Woitek for numerous valuable suggestions incorporated in the article, which shaped it in important respects. Huff gratefully acknowledges support provided by a Leverhulme Research Fellowship and grants for data collection from the East Asia National Resource Center, Stanford University, the Carnegie Trust, Scotland, the British Academy, and the Royal Economic Society. -

Fairs and Festivals, (20 Nalgonda)

PRG. 179.20 (N) 750 NALGONDA CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME II ANDHRA PRADESH PART VII-B (20) • ."" ( 20. Nalgonda District) A. CHANDRA SEKHAR OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE Superintendent of Census Operations, Andhra Pradesh Price: Rs. 5.25 P. or 12 Sh. 4d. or $ 1.89 c. 1961 CENSUS PUBLICATIONS, ANDHRA PRADESH ( All the Census Publications of this State bear Vol. No. II ) PART I-A General Report PART I-B Report on Vital Statistics PART I-C Subsidiary Tables PART II-A General Population Tables PART II-B (i) Economic Tables [B-1 to B-IV] PART II-B (ii) Economic Tables [B-V to B-IX] PART ll-C Cultural and Migration Tables PART III Household Economic Tables PART IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments (with Subsidiary Tables) PART IV-B Housing and Establishment Tables PART V-A Special Tables for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes PART V-B Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes PART VI Village Survey Monographs (46) PART VII-A (1) I I Handicrafts Survey Reports (Selected Crafts) PART VIT-A (2) J PART VII-B (1 to 20) Fairs and Festivals (Separate Book for each District) PART VIII-A Administration Report-Enumeration I I (Not Jor sale) PART VIII-B Administra tion Report-Tabulation J PART IX State Atlas PART X Special Report on Hyderabad City District Census Handbooks (Separate Volume Jor each District) :2 SlJ..... (l) I ,......; () » ~ <: ~ ~ -.(l) "'<! ~ 0 tl'l >-+:I ~ ~ K'! I") ~ :::.... a.. (JQ . -..: . _ ~ ~ ~ . (JQ ~ ~I") ;:::; v.,~ SlJ .,CI:l to -. ::r t-- C ~ ::s ~ !J.9 .