Maori Treasure Box

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

African Textiles in the V&A 1852- 2000

Title Producing and Collecting for Empire: African Textiles in the V&A 1852- 2000 Type Thesis URL http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/6141/ Date 2012 Citation Stylianou, Nicola Stella (2012) Producing and Collecting for Empire: African Textiles in the V&A 1852-2000. PhD thesis, University of the Arts London and the Victoria and Albert Museum. Creators Stylianou, Nicola Stella Usage Guidelines Please refer to usage guidelines at http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected]. License: Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Unless otherwise stated, copyright owned by the author Producing and Collecting for Empire: African Textiles in the V&A 1852-2000 Nicola Stella Stylianou Submitted to University of the Arts London for PhD Examination October 2012 This is an AHRC funded Collaborative PhD between Research Centre for Transnational Art, Identity and Nation (TrAIN) at UAL and the Victoria and Albert Museum. Volume 1 Abstract Producing and collecting for Empire: African textiles in the V&A 1850-2000 The aim of this project is to examine the African textiles in the Victoria and Albert Museum and how they reflect the historical and cultural relationship between Britain and Africa. As recently as 2009 the V&A’s collecting policy stated ‘Objects are collected from all major artistic traditions … The Museum does not collect historic material from Oceania and Africa south of the Sahara’ (V&A 2012 Appendix 1). Despite this a significant number of Sub-Saharan African textiles have come into the V&A during the museum’s history. The V&A also has a large number of textiles from North Africa, both aspects of the collection are examined. -

Rajguru the World in the Garden Final

1 Dr Megha Rajguru Senior Lecturer, History of Art and Design, University of Brighton [email protected] The World in the Garden: Ethnobotany in the Contemporary Horniman Museum Garden, London. Abstract This article traces the evolution of the Horniman Museum garden, London, from the nineteenth-century and focuses on its current design. The design (2007-present day) mimics the founder Frederick Horniman’s approach to collecting and displaying, which is now described as ethnobotanical, but with an increased focus on unifying the museum collections and garden. The Museum contains displays of ethnological, zoological and entomological specimens. Sections of the contemporary garden showcase world plants, which are part of the ethnological museum trail, leading visitors from the gallery into the garden, to witness nature and culture intertwined. Interpretation panels describe world cultures’ relationships with botany. Through this process of display and interpretation, the museum produces ethnobotanical knowledge for its visitors. The mode of construction of knowledge in this didactic garden is two-fold. It is materialist and representational, while providing space for the visitor for a translation of ethnographic meanings. 2 I borrow James Clifford’s “Ethnographic Allegory” (1986) to examine the ways in which this method of curating enables processes of translation and the role of the garden within this. While this curating approach attempts to mimic Horniman’s vision, it produces a historicist vision of world cultures – objects from the past juxtaposed with plants growing in the garden and descriptions of contemporary lives. The garden as a living entity provides the allegorical process, the element of coevalness. -

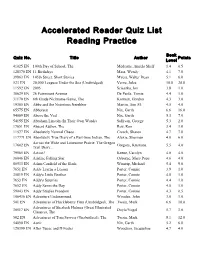

AR Quiz List by Title

Accelerated Reader Quiz List Reading Practice Book Quiz No. Title Author Points Level 41025 EN 100th Day of School, The Medearis, Angela Shelf 1.4 0.5 128370 EN 11 Birthdays Mass, Wendy 4.1 7.0 39863 EN 145th Street: Short Stories Myers, Walter Dean 5.1 6.0 523 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Unabridged) Verne, Jules 10.0 28.0 11592 EN 2095 Scieszka, Jon 3.8 1.0 30629 EN 26 Fairmount Avenue De Paola, Tomie 4.4 1.0 31170 EN 6th Grade Nickname Game, The Korman, Gordon 4.3 3.0 19385 EN Abby and the Notorious Neighbor Martin, Ann M. 4.5 4.0 65575 EN Abhorsen Nix, Garth 6.6 16.0 54089 EN Above the Veil Nix, Garth 5.3 7.0 54155 EN Abraham Lincoln (In Their Own Words) Sullivan, George 5.3 2.0 17651 EN Absent Author, The Roy, Ron 3.4 1.0 11577 EN Absolutely Normal Chaos Creech, Sharon 4.7 7.0 117771 EN Absolutely True Diary of a Part-time Indian, The Alexie, Sherman 4.0 6.0 Across the Wide and Lonesome Prairie: The Oregon 17602 EN Gregory, Kristiana 5.5 4.0 Trail Diary... 79585 EN Action! Keene, Carolyn 4.8 4.0 36046 EN Adaline Falling Star Osborne, Mary Pope 4.6 4.0 86533 EN Adam Canfield of the Slash Winerip, Michael 5.4 9.0 7651 EN Addy Learns a Lesson Porter, Connie 3.9 1.0 35819 EN Addy's Little Brother Porter, Connie 4.0 1.0 7653 EN Addy's Surprise Porter, Connie 4.4 1.0 7652 EN Addy Saves the Day Porter, Connie 4.0 1.0 59043 EN Addy Studies Freedom Porter, Connie 4.3 0.5 106436 EN Adventure Underground Wooden, John 3.0 1.0 501 EN Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Unabridged), The Twain, Mark 6.6 18.0 Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (Great Illustrated 30517 EN Doyle/Vogel 5.7 3.0 Classics), The 502 EN Adventures of Tom Sawyer (Unabridged), The Twain, Mark 8.1 12.0 54090 EN Aenir Nix, Garth 5.2 6.0 120399 EN After Tupac and D Foster Woodson, Jacqueline 4.7 4.0 353 EN Afternoon of the Elves Lisle, Janet Taylor 5.0 4.0 14651 EN Afternoon on the Amazon Osborne, Mary Pope 2.6 1.0 119440 EN Airman Colfer, Eoin 5.8 16.0 5051 EN Alan and Naomi Levoy, Myron 3.3 5.0 19738 EN Alaskan Adventure, The Dixon, Franklin W. -

Pettitt (20Th August 1937 - 26Th March 2009): 2 Zoological Curator at Manchester Museum

NatSCA News Issue 19 Index Charles Arthur William ‘Bill’ Pettitt (20th August 1937 - 26th March 2009): 2 Zoological Curator at Manchester Museum. - Geoff Hancock and Michael Hounsome Editorial - Jan Freedman 7 View from the Chair - Paul Brown 8 NatSCA AGM Minutes 9 Papers from the conference *Review of NatSCA conference at Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery 18 6th-7th May 2010 - Hayleigh Jutson *Shout it from the Green Rooftop: raising the profile of Natural Sciences at the 22 Horniman Museum and Gardens. - Jo Hatton and Emily Dutton *Wild about Plymouth: The Family Friendly Natural History Group in Plymouth 30 - Jan Freedman, Helen Fothergill, and Peter Smithers *Volunteering Flagship at Leicester County Museums 38 - Carolyn Holmes *One step back, two steps forward—doing the SSN shimmy 47 - Rebecca Elson *Increasing access to collections through partnerships 49 - Angela Smith *Darwin 200—beyond the bicentenary 54 - Paolo Viscardi *Google me a penguin: Natural History Collections and the web 60 - Mark Carnall *Well, it worked for me...A personal view of the new Natural History Gallery 65 at Norwich Castle Museum - Tony Irwin A Tiger in a Library 72 - Sammuel Alberti and Andrea Winn The Odontological Collections at the Royal College of Surgeons of England 77 - Milly Farrell Live animals in Museums and Public Engagement 82 - Nicola Newton Preservation of botanical specimens in fluids 85 - Simon Moore News, Notices and Adverts 89 1 NatSCA News Issue 19 Charles Arthur William “Bill” Pettitt (20 August 1937 – 26 March 2009): Zoological Curator at Manchester Museum E. Geoffrey Hancock 1 & Dr Michael V. Hounsome 2 1Hunterian Museum (Zoology), Graham Kerr Building, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, G12 8QQ Email: [email protected] 2Hooper's Farm, Offwell, Honiton, Devon, EX14 9SR Email: [email protected] Fig. -

2005-Enders-Game.Pdf

Daniel Boone Regional Library Book Discussion Kit DBRL One READ Selection 2005 Callaway County / Columbia / Southern Boone County Public Libraries www.dbrl.org Ender’s Game by Orson Scott Card Page 1 Tips for Book Discussions from Washington Center for the Book at Seattle Public Library Reading Critically Books that make excellent choices for discussion groups have a good plot, well-drawn characters, and a polished style. These books usually present the author’s view of an important truth and not infrequently send a message to the reader. Good books for discussion move the reader and stay in the mind long after the book is read and the discussion is over. These books can be read more than once, and each time we learn something new. Reading for a book discussion—whether you are the leader or simply a participant—differs from reading purely for pleasure. As you read a book chosen for a discussion, ask questions and mark down important pages you might want to refer back to. Make notes like, "Is this significant?" or "Why does the author include this?" Making notes as you go slows down your reading but gives you a better sense of what the book is really about and saves you the time of searching out important passages later. Obviously, asking questions as you go means you don't know the answer yet, and often you never do discover the answers. But during discussion of your questions, others may provide insight for you. Don't be afraid to ask hard questions because often the author is presenting difficult issues for that very purpose. -

Watertown Bedding Shop

Property of the Watertown Historical Society C0 watertownhistoricalsociety.org cs es ee ^j, ^J? • 1 on es **9*m* LU 2 Vol. 46 No. 29 PUBLISHED BY THE BEE PUBLISHING COMPANY, INC. My 18,1991 ^^^ LU LL 1— 64 Pages Price 35 cents fj £%.% C LU ^ cs a"*^ iii i^J <r Serving Watertown and Oakville Since 1947 •W V' " c£ (\J 3 Budget Cuts Await Council Decision There was no definite word WEA president Robert Grady from the Town Council Monday said Tuesday. about additional cuts to be made "We've made a presentation to the already mangled school that will save the positions," he budget. Twenty-one teaching said, referring to the teaching positions are slated to be slashed and clerical positions in jeop- in order to reach the $1 million ardy. "We can't make a formal cut made by the council follow- presentation until after the refer- ing the most recent budget de- endum," he said, adding that the feat. Board of Education mem- presentation was made to an bers have voted to oppose any informal negotiating team. further reductions in the S19.9 "What the presentation in- million budget cludes are things that bother "We're working once again people," Mr Grady said. "It to send a budget to referendum," would keep the system relatively Town Council Finance Director intact." Pete Scanlon told council mem- bers and an audience made up Town Gets Postcard primarily of teachers waiting to Watertown was congratulated hear word on cuts. Discussions by a representative of the Salis- are taking place with bargaining bury Connecticut Free Zone for and non-bargaining units, he declaring itself a nuclear free STRETCHED TO THE LIMIT: McDougal, a boa constrictor, stretches to a full ten-and-a-halffeet as added. -

Levell, Nicky Publicado

The poetics and prosaics of making exhibition: a personal reflection on the Centenary Gallery Autor(es): Levell, Nicky Publicado por: CIAS - Centro de Investigação em Antropologia e Saúde URL persistente: URI:http://hdl.handle.net/10316.2/41278 DOI: DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.14195/2182-7982_18_8 Accessed : 4-Oct-2021 16:30:57 A navegação consulta e descarregamento dos títulos inseridos nas Bibliotecas Digitais UC Digitalis, UC Pombalina e UC Impactum, pressupõem a aceitação plena e sem reservas dos Termos e Condições de Uso destas Bibliotecas Digitais, disponíveis em https://digitalis.uc.pt/pt-pt/termos. Conforme exposto nos referidos Termos e Condições de Uso, o descarregamento de títulos de acesso restrito requer uma licença válida de autorização devendo o utilizador aceder ao(s) documento(s) a partir de um endereço de IP da instituição detentora da supramencionada licença. Ao utilizador é apenas permitido o descarregamento para uso pessoal, pelo que o emprego do(s) título(s) descarregado(s) para outro fim, designadamente comercial, carece de autorização do respetivo autor ou editor da obra. Na medida em que todas as obras da UC Digitalis se encontram protegidas pelo Código do Direito de Autor e Direitos Conexos e demais legislação aplicável, toda a cópia, parcial ou total, deste documento, nos casos em que é legalmente admitida, deverá conter ou fazer-se acompanhar por este aviso. impactum.uc.pt digitalis.uc.pt The poetics and prosaies ofmaking exhibitions, A personal reflection on the Centenary Galíery Nicky Levell Uníversity College london Department of Anthropology Gower Street London WC1E 6BT, United Ktngdom [email protected] Abstract By selecting and describing different life-stages in the production of one particular exhibition - the permanent ethnographic displays in the Centenary Gallery of the Homiman Museum, London - this paper examines the dialogical nature of exhibition making. -

The Persisting Idea of American Treasure Hunting

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 24 Issue 4 Article 4 10-1-1984 The Persisting Idea of American Treasure Hunting Ronald W. Walker Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Walker, Ronald W. (1984) "The Persisting Idea of American Treasure Hunting," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 24 : Iss. 4 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol24/iss4/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Walker: The Persisting Idea of American Treasure Hunting the persisting idea of american treasure hunting ronald W walker he carried a magic divining rod A miraculous crystal stone by which in the darkened crown of his hat he could fix a spot unknown leo leonard twinem A ballad of old pocock vermont 1929 there is only one way of understanding a cultural phenomenon which is alien to one s own ideological pattern and that is to place oneself at its very centre and from there to track down all the values that radiate from it mircea eliade the forge andtheand the crucible 1956 11 toute vue des choseschases qui n est pas etrangeenrange est fausse paul valery as quoted in hamlets mill 1 the following essay was originally written for a general scholarly audience even though it is now being published in a latter day saint context I1 have chosen to -

Copyrighted Material

COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL The British Museum. 005_688410-ch01.indd5_688410-ch01.indd 4 55/13/10/13/10 22:17:17 PMPM LONDON here cannot be a city in the world with more free things to Tdo than London. As well as the world-beating Natural His- tory Museum with its enormous blue whale and robot dinosaurs, the interactive Science Museum and the British Museum, home to the world-famous Rosetta Stone, there’s plenty of royal pomp. Highlights include Changing the Guard at Buckingham Palace, the Ceremony of the Keys at the Tower of London and Trooping the Colour. The Oxford and Cambridge boat race is staged annually along the Thames, while the colourful Notting Hill Carnival is the biggest of its kind in Europe. There’s the celebrity chef endorsed Borough Market that’s fantastic 005_688410-ch01.indd5_688410-ch01.indd 5 55/13/10/13/10 22:17:17 PMPM 6 CHAPTER 1 LONDON for food shopping, while free comedy nights are staged at the Theatre Royal in Stratford, master-classes at the Royal Academy of Music and concerts at the Royal Opera House. There are Jack the Ripper walking tours for the ghoulish, bird walks in Regent’s Park and the deer to take in at Richmond Park. You can start a revolution from Speaker’s Cor- ner in Hyde Park or plant a foot on each side of the globe on the Greenwich Meridian line at the Royal Observatory. Art highlights include the Turners at Tate Britain, while the National Gallery is home to more than 2,300 paintings. -

Great Church Crisis,” Public Life, and National Identity in Late-Victorian and Edwardian Britain

The “Great Church Crisis,” Public Life, and National Identity in late-Victorian and Edwardian Britain Author: Bethany Tanis Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/1969 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2009 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Boston College The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Department of History THE “GREAT CHURCH CRISIS,” PUBLIC LIFE, AND NATIONAL IDENTITY IN LATE-VICTORIAN AND EDWARDIAN BRITAIN a dissertation by BETHANY TANIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2009 © copyright by BETHANY MICHELE TANIS 2009 Dissertation Abstract The “Great Church Crisis,” Public Life, and National Identity in late-Victorian and Edwardian Britain Bethany Tanis Dissertation Advisor: Peter Weiler 2009 This dissertation explores the social, cultural, and political effects of the “Great Church Crisis,” a conflict between the Protestant and Anglo-Catholic (or Ritualist) parties within the Church of England occurring between 1898 and 1906. Through a series of case studies, including an examination of the role of religious controversy in fin-de-siècle Parliamentary politics, it shows that religious belief and practice were more important in turn-of-the-century Britain than has been appreciated. The argument that the onset of secularization in Britain as defined by both a decline in religious attendance and personal belief can be pushed back until at least the 1920s or 1930s is not new. Yet, the insight that religious belief and practice remained a constituent part of late-Victorian and Edwardian national identity and public life has thus far failed to penetrate political, social, and cultural histories of the period. -

Model Lives: the Changing Meanings of Miniature Ethnographic Models from Acquisition to Interpretation at the Horniman Free Museum 1894-1898

Model Lives: The Changing Meanings of Miniature Ethnographic Models from Acquisition to Interpretation at the Horniman Free Museum 1894-1898 Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Leicester by Ryan Nutting School of Museum Studies June 2017 Model Lives: The Changing Meanings of Miniature Ethnographic Models from Acquisition to Interpretation at the Horniman Free Museum 1894-1898 Ryan Nutting Although many contemporary museums possess collections of miniature ethnographic models, few scholars have explored how these objects emphasize ideas of intellectual control. This thesis examines the use and interpretation of miniature ethnographic models in the late nineteenth century. I demonstrate how the interpretation of these objects reinforced British intellectual control over the peoples of India and Burma during this period by focusing on four sets of miniature ethnographic models purchased by Frederick Horniman in the mid-1890s and displayed in the Horniman Free Museum until it closed in January 1898. Building on the theories of miniature objects developed by Susan Stewart and others, scholarship on the development of tourist art, late nineteenth-century museum education theories, and postcolonial theories the thesis examines the biography of these objects between 1894 and 1898. By drawing on archival documents from the museum, articles about Horniman and the museum from this period, and newspaper articles chronicling Horniman’s journal of his travels between 1894 and 1896, this thesis traces the interpretation of these miniature models from their purchase through their display within the museum to the description of these models by visitors to the museum, and in each case shows how these models embodied notions of intellectual control over the peoples of India and Burma. -

Guide for the Use of Visitors to the Horniman Museum and Library

ILL INOI S UN IVERSiTY OF ILLINOIS AT UlR BANA-CHAMPAIG N PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Brittle Books Project, 2012. COPYRIGHT NOTIFICATION In Public Domain. Published prior to 1923. This digital copy was made from the printed version held by the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. It was made in compliance with copyright law. Prepared for the Brittle Books Project, Main Library, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign by Northern Micrographics Brookhaven Bindery La Crosse, Wisconsin 2012 • : ' ? ' " '.--- i::" '" ." " I " .. " ' - . , ' " , - LONDON CO TYCOUNCIL. S. F.OR .THE USE OF VISITORS , b TO Ei HOR NI M AN MUSEUM AND LRARY, std3 ";,t FOREST HILL , LONDON, S:E 'pt a(Sycond editiong rewriten - 912 OPEN FREE DAILY. 2 USET)1 THE w Weekdays, April to Septembr, ,inclsive, iI a.m. to 8 p.m. - Ii October to _March, iclusive, i a.m. to 6 p -.m Sundays, all the year round, p.m. to 9 p.m. -Closed only on Christmas Day. , ieekdays, all the year round, i a.m. to g p.m. Strndays; all the year round,i 3p.m. to g p.m. Closed on Chri tmas Pay Good iiay. ,and Bank Holidays. wenay be p rchased, either directilor throghc any Bookseller, from 2P S. KING ANIppoN, ... gents ot he sa thepubi ations of Londo i Coos ny Co c i. 4 g'.1 y558- Price-"ld _Post-free24d. - oc 4121 2-10og2 : . _ CA rlij C ii1 1, i:II :' .i .i ,la I ':i TT.~~z~rvrr~Be~CIY;-- 7N6~P~rcf~c- i.