1 United States of America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK-HFM Tupolev Tu-134 CSA -large OK on fin 91 2 £3 CC211 G-31-962 HP Jetstream 31 American eagle 92 2 £1 CC368 N4213X Douglas DC-6 Northern Air Cargo 88 4 £2 CC373 G-BFPV C-47 ex Spanish AF T3-45/744-45 78 1 £4 CC446 G31-862 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC487 CS-TKC Boeing 737-300 Air Columbus 93 3 £2 CC489 PT-OKF DHC8/300 TABA 93 2 £2 CC510 G-BLRT Short SD-360 ex Air Business 87 1 £2 CC567 N400RG Boeing 727 89 1 £2 CC573 G31-813 HP Jetstream 31 white 88 1 £1 CC574 N5073L Boeing 727 84 1 £2 CC595 G-BEKG HS 748 87 2 £2 CC603 N727KS Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC608 N331QQ HP Jetstream 31 white 88 2 £1 CC610 D-BERT DHC8 Contactair c/s 88 5 £1 CC636 C-FBIP HP Jetstream 31 white 88 3 £1 CC650 HZ-DG1 Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC732 D-CDIC SAAB SF-340 Delta Air 89 1 £2 CC735 C-FAMK HP Jetstream 31 Canadian partner/Air Toronto 89 1 £2 CC738 TC-VAB Boeing 737 Sultan Air 93 1 £2 CC760 G31-841 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC762 C-GDBR HP Jetstream 31 Air Toronto 89 3 £1 CC821 G-DVON DH Devon C.2 RAF c/s VP955 89 1 £1 CC824 G-OOOH Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 3 £1 CC826 VT-EPW Boeing 747-300 Air India 89 3 £1 CC834 G-OOOA Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 4 £1 CC876 G-BHHU Short SD-330 89 3 £1 CC901 9H-ABE Boeing 737 Air Malta 88 2 £1 CC911 EC-ECR Boeing 737-300 Air Europa 89 3 £1 CC922 G-BKTN HP Jetstream 31 Euroflite 84 4 £1 CC924 I-ATSA Cessna 650 Aerotaxisud 89 3 £1 CC936 C-GCPG Douglas DC-10 Canadian 87 3 £1 CC940 G-BSMY HP Jetstream 31 Pan Am Express 90 2 £2 CC945 7T-VHG Lockheed C-130H Air Algerie -

Appendix 25 Box 31/3 Airline Codes

March 2021 APPENDIX 25 BOX 31/3 AIRLINE CODES The information in this document is provided as a guide only and is not professional advice, including legal advice. It should not be assumed that the guidance is comprehensive or that it provides a definitive answer in every case. Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 000 ANTONOV DESIGN BUREAU 001 AMERICAN AIRLINES 005 CONTINENTAL AIRLINES 006 DELTA AIR LINES 012 NORTHWEST AIRLINES 014 AIR CANADA 015 TRANS WORLD AIRLINES 016 UNITED AIRLINES 018 CANADIAN AIRLINES INT 020 LUFTHANSA 023 FEDERAL EXPRESS CORP. (CARGO) 027 ALASKA AIRLINES 029 LINEAS AER DEL CARIBE (CARGO) 034 MILLON AIR (CARGO) 037 USAIR 042 VARIG BRAZILIAN AIRLINES 043 DRAGONAIR 044 AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS 045 LAN-CHILE 046 LAV LINEA AERO VENEZOLANA 047 TAP AIR PORTUGAL 048 CYPRUS AIRWAYS 049 CRUZEIRO DO SUL 050 OLYMPIC AIRWAYS 051 LLOYD AEREO BOLIVIANO 053 AER LINGUS 055 ALITALIA 056 CYPRUS TURKISH AIRLINES 057 AIR FRANCE 058 INDIAN AIRLINES 060 FLIGHT WEST AIRLINES 061 AIR SEYCHELLES 062 DAN-AIR SERVICES 063 AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 064 CSA CZECHOSLOVAK AIRLINES 065 SAUDI ARABIAN 066 NORONTAIR 067 AIR MOOREA 068 LAM-LINHAS AEREAS MOCAMBIQUE Page 2 of 19 Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 069 LAPA 070 SYRIAN ARAB AIRLINES 071 ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 072 GULF AIR 073 IRAQI AIRWAYS 074 KLM ROYAL DUTCH AIRLINES 075 IBERIA 076 MIDDLE EAST AIRLINES 077 EGYPTAIR 078 AERO CALIFORNIA 079 PHILIPPINE AIRLINES 080 LOT POLISH AIRLINES 081 QANTAS AIRWAYS -

Airline Schedules

Airline Schedules This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on January 08, 2019. English (eng) Describing Archives: A Content Standard Special Collections and Archives Division, History of Aviation Archives. 3020 Waterview Pkwy SP2 Suite 11.206 Richardson, Texas 75080 [email protected]. URL: https://www.utdallas.edu/library/special-collections-and-archives/ Airline Schedules Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Series Description .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 - Page 2 - Airline Schedules Summary Information Repository: -

Abx Air Reaches Tentative Agreement with Pilot Union

Employee Portal Corporate Store ATSG ABX AIR REACHES TENTATIVE AGREEMENT WITH PILOT UNION WILMINGTON, Ohio--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Air Transport Services Group, Inc. (ATSG) said today that its ABX Air subsidiary has reached a tentative agreement to amend the collective bargaining agreement with its pilot group, currently numbering more than 230 flight crew members. ABX Air’s pilots are represented by the Airline Professionals Association of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, Local 1224 (IBT). The tentative agreement would extend for six (6) years from the date of ratification by the ABX Air pilots. “We are optimistic that this tentative agreement, if ratified, will give ABX Air the opportunity to compete for new growth and provide all our employees with opportunities for career advancement and financial stability,” said ABX Air president David Soaper, “while ensuring that ABX Air continues to provide the excellent service its customers expect.” Terms of the tentative agreement were not disclosed but will be presented to the ABX Air pilot group prior to holding a ratification vote. The vote is expected to be completed prior to the end of the year. About Air Transport Services Group, Inc. (ATSG) ATSG is a leading provider of aircraft leasing and air cargo transportation and related services to domestic and foreign air carriers and other companies that outsource their air cargo lift requirements. ATSG, through its leasing and airline subsidiaries, is the world's largest owner and operator of converted Boeing 767 freighter aircraft. Through its principal subsidiaries, including three airlines with separate and distinct U.S. FAA Part 121 Air Carrier certificates, ATSG provides aircraft leasing, air cargo lift, passenger ACMI and charter services, aircraft maintenance services and airport ground services. -

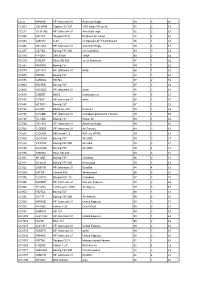

Automated Flight Statistics Report For

DENVER INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT TOTAL OPERATIONS AND TRAFFIC March 2014 March YEAR TO DATE % of % of % Grand % Grand Incr./ Incr./ Total Incr./ Incr./ Total 2014 2013 Decr. Decr. 2014 2014 2013 Decr. Decr. 2014 OPERATIONS (1) Air Carrier 36,129 35,883 246 0.7% 74.2% 99,808 101,345 (1,537) -1.5% 73.5% Air Taxi 12,187 13,754 (1,567) -11.4% 25.0% 34,884 38,400 (3,516) -9.2% 25.7% General Aviation 340 318 22 6.9% 0.7% 997 993 4 0.4% 0.7% Military 15 1 14 1400.0% 0.0% 18 23 (5) -21.7% 0.0% TOTAL 48,671 49,956 (1,285) -2.6% 100.0% 135,707 140,761 (5,054) -3.6% 100.0% PASSENGERS (2) International (3) Inbound 68,615 58,114 10,501 18.1% 176,572 144,140 32,432 22.5% Outbound 70,381 56,433 13,948 24.7% 174,705 137,789 36,916 26.8% TOTAL 138,996 114,547 24,449 21.3% 3.1% 351,277 281,929 69,348 24.6% 2.8% International/Pre-cleared Inbound 42,848 36,668 6,180 16.9% 121,892 102,711 19,181 18.7% Outbound 48,016 39,505 8,511 21.5% 132,548 108,136 24,412 22.6% TOTAL 90,864 76,173 14,691 19.3% 2.0% 254,440 210,847 43,593 20.7% 2.1% Majors (4) Inbound 1,698,200 1,685,003 13,197 0.8% 4,675,948 4,662,021 13,927 0.3% Outbound 1,743,844 1,713,061 30,783 1.8% 4,724,572 4,700,122 24,450 0.5% TOTAL 3,442,044 3,398,064 43,980 1.3% 75.7% 9,400,520 9,362,143 38,377 0.4% 75.9% National (5) Inbound 50,888 52,095 (1,207) -2.3% 139,237 127,899 11,338 8.9% Outbound 52,409 52,888 (479) -0.9% 139,959 127,940 12,019 9.4% TOTAL 103,297 104,983 (1,686) -1.6% 2.3% 279,196 255,839 23,357 9.1% 2.3% Regionals (6) Inbound 382,759 380,328 2,431 0.6% 1,046,306 1,028,865 17,441 1.7% Outbound -

Bankruptcy Tilts Playing Field Frank Boroch, CFA 212 272-6335 [email protected]

Equity Research Airlines / Rated: Market Underweight September 15, 2005 Research Analyst(s): David Strine 212 272-7869 [email protected] Bankruptcy tilts playing field Frank Boroch, CFA 212 272-6335 [email protected] Key Points *** TWIN BANKRUPTCY FILINGS TILT PLAYING FIELD. NWAC and DAL filed for Chapter 11 protection yesterday, becoming the 20 and 21st airlines to do so since 2000. Now with 47% of industry capacity in bankruptcy, the playing field looks set to become even more lopsided pressuring non-bankrupt legacies to lower costs further and low cost carriers to reassess their shrinking CASM advantage. *** CAPACITY PULLBACK. Over the past 20 years, bankrupt carriers decreased capacity by 5-10% on avg in the year following their filing. If we assume DAL and NWAC shrink by 7.5% (the midpoint) in '06, our domestic industry ASM forecast goes from +2% y/y to flat, which could potentially be favorable for airline pricing (yields). *** NWAC AND DAL INTIMATE CAPACITY RESTRAINT. After their filing yesterday, NWAC's CEO indicated 4Q:05 capacity could decline 5-6% y/y, while Delta announced plans to accelerate its fleet simplification plan, removing four aircraft types by the end of 2006. *** BIGGEST BENEFICIARIES LIKELY TO BE LOW COST CARRIERS. NWAC and DAL account for roughly 26% of domestic capacity, which, if trimmed by 7.5% equates to a 2% pt reduction in industry capacity. We believe LCC-heavy routes are likely to see a disproportionate benefit from potential reductions at DAL and NWAC, with AAI, AWA, and JBLU in particular having an easier path for growth. -

Pilots Jump to Each Section Below Contents by Clicking on the Title Or Photo

November 2018 Aero Crew News Your Source for Pilot Hiring and More... ExpressJet is taking off with a new Pilot Contract Top-Tier Compensation and Work Rules $40/hour first-year pay $10,000 annual override for First Officers, $8,000 for Captains New-hire bonus 100% cancellation and deadhead pay $1.95/hour per-diem Generous 401(k) match Friendly commuter and reserve programs ARE YOU READY FOR EXPRESSJET? FLEET DOMICILES UNITED CPP 126 - Embraer ERJ145 Chicago • Cleveland Spend your ExpressJet career 20 - Bombardier CRJ200 Houston • Knoxville knowing United is in Newark your future with the United Pilot Career Path Program Apply today at expressjet.com/apply. Questions? [email protected] expressjet.com /ExpressJetPilotRecruiting @expressjetpilots Jump to each section Below contents by clicking on the title or photo. November 2018 20 36 24 50 32 Also Featuring: Letter from the Publisher 8 Aviator Bulletins 10 Self Defense for Flight Crews 16 Trans States Airlines 42 4 | Aero Crew News BACK TO CONTENTS the grid New Airline Updated Flight Attendant Legacy Regional Alaska Airlines Air Wisconsin The Mainline Grid 56 American Airlines Cape Air Delta Air Lines Compass Airlines Legacy, Major, Cargo & International Airlines Hawaiian Airlines Corvus Airways United Airlines CommutAir General Information Endeavor Air Work Rules Envoy Additional Compensation Details Major ExpressJet Airlines Allegiant Air GoJet Airlines Airline Base Map Frontier Airlines Horizon Air JetBlue Airways Island Air Southwest Airlines Mesa Airlines Spirit Airlines -

November 2017 Newsletter

PilotsPROUDLY For C ELEBRATINGKids Organization 34 YEARS! Pilots For KidsSM ORGANIZATION Helping Hospitalized Children Since 1983 Want to join in this year’s holiday visits? Newsletter November 2017 See pages 8-9 to contact the coordinator in your area! PFK volunteers have been visiting youngsters at Texas Children’s Hospital for 23 years. Thirteen volunteers representing United, Delta and Jet Blue joined together and had another very successful visit on June 13th. Sign up for holiday visits in your area by contacting your coordinator! “100% of our donations go to the kids” visit us at: pilotsforkids.org (2) Pilots For Kids Organization CITY: LAX/Los Angeles, CA President’s Corner... COORDINATOR: Vasco Rodriques PARTICIPANTS: Alaska Airlines Dear Members, The volunteers from the LAX Alaska Airlines Pilots Progress is a word everyone likes. The definition for Kids Chapter visited with 400 kids at the Miller of progress can be described as growth, develop- Children’s Hospital in Long Beach. This was during ment, or some form of improvement. their 2-day “Beach Carnival Day”. During the last year we experienced continual growth in membership and also added more loca- The crews made and flew paper airplanes with the tions where our visits take place. Another sign kids. When the kids landed their creations on “Run- of our growth has been our need to add a second way 25L”, they got rewarded with some cool wings! “Captain Baldy” mascot due to his popularity. Along with growth comes workload. To solve this challenge we have continually looked for ways to reduce our workload and cost through increased automation. -

World Air Transport Statistics, Media Kit Edition 2021

Since 1949 + WATSWorld Air Transport Statistics 2021 NOTICE DISCLAIMER. The information contained in this publication is subject to constant review in the light of changing government requirements and regulations. No subscriber or other reader should act on the basis of any such information without referring to applicable laws and regulations and/ or without taking appropriate professional advice. Although every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, the International Air Transport Associ- ation shall not be held responsible for any loss or damage caused by errors, omissions, misprints or misinterpretation of the contents hereof. Fur- thermore, the International Air Transport Asso- ciation expressly disclaims any and all liability to any person or entity, whether a purchaser of this publication or not, in respect of anything done or omitted, and the consequences of anything done or omitted, by any such person or entity in reliance on the contents of this publication. Opinions expressed in advertisements ap- pearing in this publication are the advertiser’s opinions and do not necessarily reflect those of IATA. The mention of specific companies or products in advertisement does not im- ply that they are endorsed or recommended by IATA in preference to others of a similar na- ture which are not mentioned or advertised. © International Air Transport Association. All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, recast, reformatted or trans- mitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval sys- tem, without the prior written permission from: Deputy Director General International Air Transport Association 33, Route de l’Aéroport 1215 Geneva 15 Airport Switzerland World Air Transport Statistics, Plus Edition 2021 ISBN 978-92-9264-350-8 © 2021 International Air Transport Association. -

Student Investment Fund

STUDENT INVESTMENT FUND 2007-2008 ANNUAL REPORT May 9, 2008 http://org.business.utah.edu/investmentfund TABLE OF CONTENTS 2007-2008 STUDENT MANAGERS........................................................................................... 3 HISTORY ...................................................................................................................................... 4 STRATEGY................................................................................................................................... 5 Davidson & Milner Portfolios .................................................................................................... 5 School Portfolio .......................................................................................................................... 6 DAVIDSON AND MILNER PERFORMANCE........................................................................ 6 Overall ........................................................................................................................................ 6 Individual Stock Performance..................................................................................................... 7 SCHOOL PERFORMANCE....................................................................................................... 9 Overall ........................................................................................................................................ 9 Individual Stock Performance.................................................................................................... -

2008 Annual Report Air Transport Services Group 2008 Annual Report

SM 2008 Annual Report Air Transport Services Group 2008 Annual Report To Our Shareholders 2008 was bound to be a year of dramatic the $91.2 million in impairment charges, full-year change for us. Shortly after our acquisition of Cargo pre-tax earnings increased 36 percent to $45.4 Holdings International (CHI) at the end of 2007, we million, versus $33.3 million for 2007. For the full were informed that our principal customer, DHL, year, our revenues were up 37 percent to $1.6 intended to dramatically restructure its U.S. operations. billion. This growth can be attributed primarily to DHL’s decision in May 2008 to pursue an air transport our CHI businesses, which contributed revenue of and sorting agreement for domestic freight with its $352.7 million for the year. Likewise, cash fl ows competitor UPS came as a tremendous shock. generated from operations increased to $161.7 million in 2008, up from $95.5 million in 2007. Just as disappointing, however, was DHL’s decision last November to suspend its domestic services in favor of handling only inbound and Operating Cash Flow 2004-2008 outbound international shipments for its global customers. Those decisions, together with the U.S. economic recession, have substantially $162M reduced the scale of our operations for DHL. $119M They also have cost us the valued contributions of thousands of men and women who had served us, and DHL, very well over the years. Wilmington, the southwest Ohio community where we are $96M based, has experienced severe economic distress. We are doing our best to remain a supportive $55M $65M corporate citizen in Wilmington, and have funded and taken an active role in many groups seeking long-term solutions to the region’s diffi culties. -

NACC Contact List July 2015 Update

ID POC Name POC Email Office Cell Filer Other Comments ABS Jets (Czech Republic) ABS Michal Pazourek (Chf Disp) [email protected] +420 220 111 388 + 420 602 205 (LKPRABPX & LKPRABY) [email protected] 852 ABX Air ABX Alain Terzakis [email protected] 937-366-2464 937-655-0703 (800) 736-3973 x62450 KILNABXD Ron Spanbauer [email protected] 937-366-2435 (937) 366-2450 24hr. AeroMexico AMX Raul Aguirre (FPF) [email protected] 011 (5255) 9132-5500 (281) 233-3406 Files thru HP/EDS Air Berlin BER Recep Bayindir [email protected] 49-30-3434-3705 EDDTBERA [email protected] AirBridgeCargo Airlines ABW Dmitry Levushkin [email protected] Chief Flight Dispatcher 7 8422 590370 Also see Volga-Dnepr Airlines Volga-Dnepr Airlines 7 8422 590067 (VDA) Air Canada ACA Richard Steele (Mgr Flt Supt) [email protected] 905 861 7572 647 328-3895 905 861 7528 CYYZACAW thru LIDO Rod Stone [email protected] 905 861 7570 Air China CCA Weston Li (Mgr. American Ops) [email protected] 604-233-1682 778-883-3315 Zhang Yuenian [email protected] Air Europa AEA Bernardo Salleras [email protected] Flight Ops [email protected] 34 971 178 281 (Ops Mgr) Air France AFR Thierry Vuillaume Thierry Vuillaume <[email protected]> +33 (0)1 41 56 78 65 LFPGAFRN Air India AIC Puneet Kataria [email protected] 718-632-0125 917-9811807 + 91-22-66858028 KJFKAICO [email protected] 718-632-0162direct Use SABRE for flights Files thru HP/EDS arriving/departing USA Air New Zealand