The Synovial Lining and Synovial Fluid Properties After Joint Arthroplasty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Making Stillbirths Visible: Changes in Indicators of Lithuanian Population During the 1995-2016 Period

Uniwersytet Medyczny w Łodzi Medical University of Lodz https://publicum.umed.lodz.pl Intramuscular Innervation Pattern of Extraocular Rectus Muscles (Superior, Inferior, Publikacja / Publication Medial and Lateral) in Humans , Haładaj Robert , Wysiadecki Grzegorz, Topol Mirosław Adres publikacji w Repozytorium URL / Publication address in https://publicum.umed.lodz.pl/info/article/AML3e183c5c8a3e4dc29d1d9c421ec762f6/ Repository Data opublikowania w Repozytorium 2020-09-11 / Deposited in Repository on Rodzaj licencji / Type of licence Attribution (CC BY) Haładaj Robert , Wysiadecki Grzegorz, Topol Mirosław: Intramuscular Innervation Cytuj tę wersję / Cite this version Pattern of Extraocular Rectus Muscles (Superior, Inferior, Medial and Lateral) in Humans , Medicina-Lithuania, vol. 55, no. Supplement 2, 2019, pp. 226-226 ISSN 1648-9233 Volume 55, Supplement 2, 2019 Issued since 1920 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Prof. Dr. Edgaras Stankevičius Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, Kaunas, Lithuania ASSOCIATE EDITORS Prof. Dr. Vita Mačiulskienė Prof. Dr. Vytenis Arvydas Skeberdis Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, Kaunas, Lithuania Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, Kaunas, Lithuania Prof. Dr. Bayram Yılmaza Prof. Dr. Andrius Macas Yeditepe University, İstanbul, Turkey Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, Kaunas, Lithuania Prof. Dr. Abdonas Tamošiūnas Assoc. Prof. Dr. Julius Liobikas Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, Kaunas, Lithuania Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, Kaunas, Lithuania EDITORIAL BOARD Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ludovico Abenavoli Prof. Dr. Ioanna Gouni-Berthold Prof. Dr. Michel Roland Magistris Prof. Dr. Ulf Simonsen Magna Græcia University, University of Cologne, Köln, Geneva University Hospitals, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Catanzaro, Italy Germany Geneva, Switzerland Denmark Prof. Dr. Mauro Alaibac Prof. Dr. Martin Grapow Dr. Philippe Menasché Prof. Dr. Jean-Paul Stahl University of Padua, Padova, Italy Universität Basel, Basel, Switzerland Hôpital Européen Georges Universite Grenoble Alpes, Grenoble cedex, France Dr. -

Synovial Joints Permit Movements of the Skeleton

8 Joints Lecture Presentation by Lori Garrett © 2018 Pearson Education, Inc. Section 1: Joint Structure and Movement Learning Outcomes 8.1 Contrast the major categories of joints, and explain the relationship between structure and function for each category. 8.2 Describe the basic structure of a synovial joint, and describe common accessory structures and their functions. 8.3 Describe how the anatomical and functional properties of synovial joints permit movements of the skeleton. © 2018 Pearson Education, Inc. Section 1: Joint Structure and Movement Learning Outcomes (continued) 8.4 Describe flexion/extension, abduction/ adduction, and circumduction movements of the skeleton. 8.5 Describe rotational and special movements of the skeleton. © 2018 Pearson Education, Inc. Module 8.1: Joints are classified according to structure and movement Joints, or articulations . Locations where two or more bones meet . Only points at which movements of bones can occur • Joints allow mobility while preserving bone strength • Amount of movement allowed is determined by anatomical structure . Categorized • Functionally by amount of motion allowed, or range of motion (ROM) • Structurally by anatomical organization © 2018 Pearson Education, Inc. Module 8.1: Joint classification Functional classification of joints . Synarthrosis (syn-, together + arthrosis, joint) • No movement allowed • Extremely strong . Amphiarthrosis (amphi-, on both sides) • Little movement allowed (more than synarthrosis) • Much stronger than diarthrosis • Articulating bones connected by collagen fibers or cartilage . Diarthrosis (dia-, through) • Freely movable © 2018 Pearson Education, Inc. Module 8.1: Joint classification Structural classification of joints . Fibrous • Suture (sutura, a sewing together) – Synarthrotic joint connected by dense fibrous connective tissue – Located between bones of the skull • Gomphosis (gomphos, bolt) – Synarthrotic joint binding teeth to bony sockets in maxillae and mandible © 2018 Pearson Education, Inc. -

Effectiveness of Distal Tibial Osteotomy

Nozaka et al. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders (2020) 21:31 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-020-3061-7 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Effectiveness of distal tibial osteotomy with distraction arthroplasty in varus ankle osteoarthritis Koji Nozaka* , Naohisa Miyakoshi, Takeshi Kashiwagura, Yuji Kasukawa, Hidetomo Saito, Hiroaki Kijima, Shuichi Chida, Hiroyuki Tsuchie and Yoichi Shimada Abstract Background: In highly active older individuals, end-stage ankle osteoarthritis has traditionally been treated using tibiotalar arthrodesis, which provides considerable pain relief. However, there is a loss of ankle joint movement and a risk of future arthrosis in the adjacent joints. Distraction arthroplasty is a simple method that allows joint cartilage repair; however, the results are currently mixed, with some reports showing improved pain scores and others showing no improvement. Distal tibial osteotomy (DTO) without fibular osteotomy is a type of joint preservation surgery that has garnered attention in recent years. However, to our knowledge, there are no reports on DTO with joint distraction using a circular external fixator. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine the effect of DTO with joint distraction using a circular external fixator for treating ankle osteoarthritis. Methods: A total of 21 patients with medial ankle arthritis were examined. Arthroscopic synovectomy and a microfracture procedure were performed, followed by angled osteotomy and correction of the distal tibia; the ankle joint was then stabilized after its condition improved. An external fixator was used in all patients, and joint distraction of approximately 5.8 mm was performed. All patients were allowed full weight-bearing walking immediately after surgery. Results: The anteroposterior and lateral mortise angle during weight-bearing, talar tilt angle, and anterior translation of the talus on ankle stress radiography were improved significantly (P < 0.05). -

Synovial Fluidfluid 11

LWBK461-c11_p253-262.qxd 11/18/09 6:04 PM Page 253 Aptara Inc CHAPTER SynovialSynovial FluidFluid 11 Key Terms ANTINUCLEAR ANTIBODY ARTHROCENTESIS BULGE TEST CRYSTAL-INDUCED ARTHRITIS GROUND PEPPER HYALURONATE MUCIN OCHRONOTIC SHARDS RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS (RA) RHEUMATOID FACTOR (RF) RICE BODIES ROPE’S TEST SEPTIC ARTHRITIS Learning Objectives SYNOVIAL SYSTEMIC LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS 1. Define synovial. VISCOSITY 2. Describe the formation and function of synovial fluid. 3. Explain the collection and handling of synovial fluid. 4. Describe the appearance of normal and abnormal synovial fluids. 5. Correlate the appearance of synovial fluid with possible cause. 6. Interpret laboratory tests on synovial fluid. 7. Suggest further testing for synovial fluid, based on preliminary results. 8. List the four classes or categories of joint disease. 9. Correlate synovial fluid analyses with their representative disease classification. 253 LWBK461-c11_p253-262.qxd 11/18/09 6:04 PM Page 254 Aptara Inc 254 Graff’s Textbook of Routine Urinalysis and Body Fluids oint fluid is called synovial fluid because of its resem- blance to egg white. It is a viscous, mucinous substance Jthat lubricates most joints. Analysis of synovial fluid is important in the diagnosis of joint disease. Aspiration of joint fluid is indicated for any patient with a joint effusion or inflamed joints. Aspiration of asymptomatic joints is beneficial for patients with gout and pseudogout as these fluids may still contain crystals.1 Evaluation of physical, chemical, and microscopic characteristics of synovial fluid comprise routine analysis. This chapter includes an overview of the composition and function of synovial fluid, and laboratory procedures and their interpretations. -

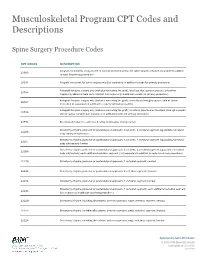

Musculoskeletal Program CPT Codes and Descriptions

Musculoskeletal Program CPT Codes and Descriptions Spine Surgery Procedure Codes CPT CODES DESCRIPTION Allograft, morselized, or placement of osteopromotive material, for spine surgery only (List separately in addition 20930 to code for primary procedure) 20931 Allograft, structural, for spine surgery only (List separately in addition to code for primary procedure) Autograft for spine surgery only (includes harvesting the graft); local (eg, ribs, spinous process, or laminar 20936 fragments) obtained from same incision (List separately in addition to code for primary procedure) Autograft for spine surgery only (includes harvesting the graft); morselized (through separate skin or fascial 20937 incision) (List separately in addition to code for primary procedure) Autograft for spine surgery only (includes harvesting the graft); structural, bicortical or tricortical (through separate 20938 skin or fascial incision) (List separately in addition to code for primary procedure) 20974 Electrical stimulation to aid bone healing; noninvasive (nonoperative) Osteotomy of spine, posterior or posterolateral approach, 3 columns, 1 vertebral segment (eg, pedicle/vertebral 22206 body subtraction); thoracic Osteotomy of spine, posterior or posterolateral approach, 3 columns, 1 vertebral segment (eg, pedicle/vertebral 22207 body subtraction); lumbar Osteotomy of spine, posterior or posterolateral approach, 3 columns, 1 vertebral segment (eg, pedicle/vertebral 22208 body subtraction); each additional vertebral segment (List separately in addition to code for -

Priority Health Spine and Joint Code List

Priority Health Joint Services Code List Category CPT® Code CPT® Code Description Joint Services 23000 Removal of subdeltoid calcareous deposits, open Joint Services 23020 Capsular contracture release (eg, Sever type procedure) Joint Services 23120 Claviculectomy; partial Joint Services 23130 Acromioplasty or acromionectomy, partial, with or without coracoacromial ligament release Joint Services 23410 Repair of ruptured musculotendinous cuff (eg, rotator cuff) open; acute Joint Services 23412 Repair of ruptured musculotendinous cuff (eg, rotator cuff) open;chronic Joint Services 23415 Coracoacromial ligament release, with or without acromioplasty Joint Services 23420 Reconstruction of complete shoulder (rotator) cuff avulsion, chronic (includes acromioplasty) Joint Services 23430 Tenodesis of long tendon of biceps Joint Services 23440 Resection or transplantation of long tendon of biceps Joint Services 23450 Capsulorrhaphy, anterior; Putti-Platt procedure or Magnuson type operation Joint Services 23455 Capsulorrhaphy, anterior;with labral repair (eg, Bankart procedure) Joint Services 23460 Capsulorrhaphy, anterior, any type; with bone block Joint Services 23462 Capsulorrhaphy, anterior, any type;with coracoid process transfer Joint Services 23465 Capsulorrhaphy, glenohumeral joint, posterior, with or without bone block Joint Services 23466 Capsulorrhaphy, glenohumeral joint, any type multi-directional instability Joint Services 23470 ARTHROPLASTY, GLENOHUMERAL JOINT; HEMIARTHROPLASTY ARTHROPLASTY, GLENOHUMERAL JOINT; TOTAL SHOULDER [GLENOID -

A MODEL of SYNOVIAL FLUID LUBRICANT COMPOSITION in NORMAL and INJURED JOINTS ME Blewis1, GE Nugent-Derfus1, TA Schmidt1, BL Schumacher1, and RL Sah1,2*

MEEuropean Blewis Cells et al .and Materials Vol. 13. 2007 (pages 26-39) DOI: 10.22203/eCM.v013a03 Model of Synovial Fluid Lubricant ISSN Composition 1473-2262 A MODEL OF SYNOVIAL FLUID LUBRICANT COMPOSITION IN NORMAL AND INJURED JOINTS ME Blewis1, GE Nugent-Derfus1, TA Schmidt1, BL Schumacher1, and RL Sah1,2* Departments of 1Bioengineering and 2Whitaker Institute of Biomedical Engineering, University of California-San Diego, La Jolla, CA Abstract Introduction The synovial fluid (SF) of joints normally functions as a The synovial fluid (SF) of natural joints normally biological lubricant, providing low-friction and low-wear functions as a biological lubricant as well as a biochemical properties to articulating cartilage surfaces through the pool through which nutrients and regulatory cytokines putative contributions of proteoglycan 4 (PRG4), traverse. SF contains molecules that provide low-friction hyaluronic acid (HA), and surface active phospholipids and low-wear properties to articulating cartilage surfaces. (SAPL). These lubricants are secreted by chondrocytes in Molecules postulated to play a key role, alone or in articular cartilage and synoviocytes in synovium, and combination, in lubrication are proteoglycan 4 (PRG4) concentrated in the synovial space by the semi-permeable (Swann et al., 1985) present in SF at a concentration of synovial lining. A deficiency in this lubricating system may 0.05-0.35 mg/ml (Schmid et al., 2001a), hyaluronan (HA) contribute to the erosion of articulating cartilage surfaces (Ogston and Stanier, 1953) at 1-4 mg/ml (Mazzucco et in conditions of arthritis. A quantitative intercompartmental al., 2004), and surface-active phospholipids (SAPL) model was developed to predict in vivo SF lubricant (Schwarz and Hills, 1998) at 0.1 mg/ml (Mazzucco et al., concentration in the human knee joint. -

Knee Joint Surgery: Open Synovectomy

Musculoskeletal Surgical Services: Open Surgical Procedures; Knee Joint Surgery: Open Synovectomy POLICY INITIATED: 06/30/2019 MOST RECENT REVIEW: 06/30/2019 POLICY # HH-5588 Overview Statement The purpose of these clinical guidelines is to assist healthcare professionals in selecting the medical service that may be appropriate and supported by evidence to improve patient outcomes. These clinical guidelines neither preempt clinical judgment of trained professionals nor advise anyone on how to practice medicine. The healthcare professionals are responsible for all clinical decisions based on their assessment. These clinical guidelines do not provide authorization, certification, explanation of benefits, or guarantee of payment, nor do they substitute for, or constitute, medical advice. Federal and State law, as well as member benefit contract language, including definitions and specific contract provisions/exclusions, take precedence over clinical guidelines and must be considered first when determining eligibility for coverage. All final determinations on coverage and payment are the responsibility of the health plan. Nothing contained within this document can be interpreted to mean otherwise. Medical information is constantly evolving, and HealthHelp reserves the right to review and update these clinical guidelines periodically. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without permission from HealthHelp. -

GLOSSARY of MEDICAL and ANATOMICAL TERMS

GLOSSARY of MEDICAL and ANATOMICAL TERMS Abbreviations: • A. Arabic • abb. = abbreviation • c. circa = about • F. French • adj. adjective • G. Greek • Ge. German • cf. compare • L. Latin • dim. = diminutive • OF. Old French • ( ) plural form in brackets A-band abb. of anisotropic band G. anisos = unequal + tropos = turning; meaning having not equal properties in every direction; transverse bands in living skeletal muscle which rotate the plane of polarised light, cf. I-band. Abbé, Ernst. 1840-1905. German physicist; mathematical analysis of optics as a basis for constructing better microscopes; devised oil immersion lens; Abbé condenser. absorption L. absorbere = to suck up. acervulus L. = sand, gritty; brain sand (cf. psammoma body). acetylcholine an ester of choline found in many tissue, synapses & neuromuscular junctions, where it is a neural transmitter. acetylcholinesterase enzyme at motor end-plate responsible for rapid destruction of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter. acidophilic adj. L. acidus = sour + G. philein = to love; affinity for an acidic dye, such as eosin staining cytoplasmic proteins. acinus (-i) L. = a juicy berry, a grape; applied to small, rounded terminal secretory units of compound exocrine glands that have a small lumen (adj. acinar). acrosome G. akron = extremity + soma = body; head of spermatozoon. actin polymer protein filament found in the intracellular cytoskeleton, particularly in the thin (I-) bands of striated muscle. adenohypophysis G. ade = an acorn + hypophyses = an undergrowth; anterior lobe of hypophysis (cf. pituitary). adenoid G. " + -oeides = in form of; in the form of a gland, glandular; the pharyngeal tonsil. adipocyte L. adeps = fat (of an animal) + G. kytos = a container; cells responsible for storage and metabolism of lipids, found in white fat and brown fat. -

Lubrication of Synovial Membrane

Ann. rheum. Dis. (1971), 30, 322 Ann Rheum Dis: first published as 10.1136/ard.30.3.322 on 1 May 1971. Downloaded from Lubrication of synovial membrane ERICEDWIN S. SCHOTTSTAEDT*PAUL,L SWANN,' From the Orthopedic Research Laboratories, Harvard Medical School at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and the Department of Mechanical Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Mass., U.S.A. Joint stiffness is a significant clinical manifestation determining factor in cartilage-on-cartilage lubrica- of patients with arthritic disease. The articulating tion (McCutchen, 1962; Linn, 1968), it has been surface area ofmost joints is to a great extent synovial suggested that lubricant viscosity might well be tissue. Cartilage-on-cartilage friction is extremely playing a significant role in synovial tissue slipperi- low and most of the resistance to joint motion is from ness (McCutchen, 1969). For these reasons an the capsule, ligaments, tendons, and skin which investigation of synovial membrane lubrication was 'ricde' over the joint on synovium (Smith, 1956; undertaken and is reported here. Johns and Wright, 1962; Barnett and Cobbold, 1969). Although analyses have been made of the types and amounts of stiffness encountered with arthritis and age (Barnett and Cobbold, 1968; Methed Wright, Dowson, and Longfield, 1969), there have Synovial tissue was obtained from the knee joints of been no studies of the lubrication mechanisms healthy cows, aged 3 to 4 years. The knees were first actually involved in synovium on synovium or inspected to insure freedom from arthritic change. Square synovium on cartilage motion. pieces of synovium, about 3 x 3 cm., with their attached capsule, were cut, washed in isotonic buffer, placed copyright. -

Radiation Synovectomy with 166Ho-Ferric Hydroxide: a First Experience

Radiation Synovectomy with 166Ho-Ferric Hydroxide: A First Experience Sedat Ofluoglu, MD1; Eva Schwameis, MD2; Harald Zehetgruber, MD2; Ernst Havlik, PhD3; Axel Wanivenhaus, MD2; Ingrid Schweeger, MD1; Konrad Weiss, MD4; Helmut Sinzinger, MD1; and Christian Pirich, MD1 1Department of Nuclear Medicine, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria; 2Department of Orthopedics, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria; 3Department of Biomedical Engineering and Physics and Ludwig Boltzmann Institute of Nuclear Medicine, Vienna, Austria; and 4Department of Nuclear Medicine, General Hospital of Wiener Neustadt, Wiener Neustadt, Austria lage, leading to the progressive loss of joint function and Radiation synovectomy (RS) is indicated when conventional significant disability. Treatment of chronic synovitis using pharmacologic treatment of chronic synovitis has not relieved radiation synovectomy (RS) aims to stop the inflammatory its symptoms. The use of radionuclides that are bound to ferric process causing pain, disability, and nonreversible structural hydroxide (FH) particles has been shown to be effective and damage to the joint (1–3). RS has been in clinical use for 166 safe for this procedure. Ho-FH macroaggregates offer prom- 50y(4) primarily as an alternative to surgical treatment (5). ising properties for RS but there is a lack of clinical data. We Safety is one of the most important aspects when radionu- investigated the efficacy and safety of 166Ho-FH in a prospective clinical trial in patients suffering from chronic synovitis. Meth- clides are applied therapeutically. The use of ferric hydrox- ods: Twenty-four intraarticular injections were performed in 22 ide (FH) particles as a carrier may offer some advantages patients receiving a mean activity of 1.11 GBq (range, 0.77–1.24 over other carriers with respect to the frequency and degree GBq) 166Ho-FH. -

Recently Discovered Interstitial Cell Population of Telocytes: Distinguishing Facts from Fiction Regarding Their Role in The

medicina Review Recently Discovered Interstitial Cell Population of Telocytes: Distinguishing Facts from Fiction Regarding Their Role in the Pathogenesis of Diverse Diseases Called “Telocytopathies” Ivan Varga 1,*, Štefan Polák 1,Ján Kyseloviˇc 2, David Kachlík 3 , L’ubošDanišoviˇc 4 and Martin Klein 1 1 Institute of Histology and Embryology, Faculty of Medicine, Comenius University in Bratislava, 813 72 Bratislava, Slovakia; [email protected] (Š.P.); [email protected] (M.K.) 2 Fifth Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Comenius University in Bratislava, 813 72 Bratislava, Slovakia; [email protected] 3 Institute of Anatomy, Second Faculty of Medicine, Charles University, 128 00 Prague, Czech Republic; [email protected] 4 Institute of Medical Biology, Genetics and Clinical Genetics, Faculty of Medicine, Comenius University in Bratislava, 813 72 Bratislava, Slovakia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +421-90119-547 Received: 4 December 2018; Accepted: 11 February 2019; Published: 18 February 2019 Abstract: In recent years, the interstitial cells telocytes, formerly known as interstitial Cajal-like cells, have been described in almost all organs of the human body. Although telocytes were previously thought to be localized predominantly in the organs of the digestive system, as of 2018 they have also been described in the lymphoid tissue, skin, respiratory system, urinary system, meninges and the organs of the male and female genital tracts. Since the time of eminent German pathologist Rudolf Virchow, we have known that many pathological processes originate directly from cellular changes. Even though telocytes are not widely accepted by all scientists as an individual and morphologically and functionally distinct cell population, several articles regarding telocytes have already been published in such prestigious journals as Nature and Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences.