Evaluation of Surface Transportation Funding Alternatives Using Criteria System Established Through a Delphi Survey of Texas Tr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Secure Synopsis

INSIGHTSIAS SIMPLIFYING IAS EXAM PREPARATION SECURE SYNOPSIS MAINS 2019 GS -I FEBRUARY 2019 www.insightsactivelearn.com | www.insightsonindia.com SECURE SYNOPSIS NOTE: Please remember that following ‘answers’ are NOT ‘model answers’. They are NOT synopsis too if we go by definition of the term. What we are providing is content that both meets demand of the question and at the same time gives you extra points in the form of background information. www.insightsonindia.com 1 www.insightsias.com SECURE SYNOPSIS Table of Contents Topic– Indian culture will cover the salient aspects of Art Forms, Literature and Architecture from ancient to modern times ________________________________________________________________________________ 4 Q) Benode Behari Mukherjee made great strides in Indian paintings besides his physical disability. Discuss. (250 words) ____________________________________________________________________ 4 Q) Discuss the emergence and evolution of Buddhist art in India. (250 words) ________________ 5 Q) Avadhana is a unique classical Indian art of spontaneous creation. Discuss. (250 words) ____ 7 Q) Literary account of foreigners proved extremely useful in writing the history of Ancient India. Discuss. (250 words) ___________________________________________________________________ 8 Q) Kabir was one of the chief exponents of the Bhakti movement in the medieval period. Discuss the Relevance of the teachings of Kabir in Contemporary India ? (250 words) _______________ 10 Q) The Vijayanagar empire architecture was heavily borrowed from the earlier dynasties of the region. Analyze. (250 words) ____________________________________________________________ 11 Q) The cultural creativity and intellectual efflorescence that were the hallmarks of the European Renaissance were conspicuous by their absence in the Indian situation. Comment. (250 words)13 Q) Safeguarding the Indian art heritage is the need of the moment. -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2013 [Price: Rs. 26.40 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 9] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, MARCH 6, 2013 Maasi 22, Nandhana, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2044 Part VI—Section 4 Advertisements by private individuals and private institutions CONTENTS PRIVATE ADVERTISEMENTS Pages Change of Names .. 487-552 NOTICE NO LEGAL RESPONSIBILITY IS ACCEPTED FOR THE PUBLICATION OF ADVERTISEMENTS REGARDING CHANGE OF NAME IN THE TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE. PERSONS NOTIFYING THE CHANGES WILL REMAIN SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR THE LEGAL CONSEQUENCES AND ALSO FOR ANY OTHER MISREPRESENTATION, ETC. (By Order) Director of Stationery and Printing. CHANGE OF NAMES 7399. I, Jain Banu, wife of Thiru Abdul Khadar Jailani, 7402. My son, S. Tamilarasan, born on 7th June 1995 born on 19th August 1967 (native district: Virudhunagar), (native district: Madurai), residing at No. 48A, Chinnachamy residing at Old No. 189, New No. 190, Sammanthapuram Street, Elumalai Post, Peraiyur Taluk, Madurai-625 535, Seethakathi Street, Rajapalayam Post, Virudhunagar- shall henceforth be known as S. IRULANDI. 626 117, shall henceforth be known as JAINAMMA. SUBBIAH. JAIN BANU. Madurai, 25th February 2013. (Father.) Virudhunagar, 25th February 2013. 7403. My son, S. Siththik, born on 28th July 1998 7400. I, P. Chenna Kasavan, son of Thiru S. Pitchai, (native district: Dindugul), residing at No. 91, Mattupatti born on 26th March 1993 (native district: Theni), residing at No. 15, Amman Sannathi Street, Cumbum Main Road, South Extension, Dindugul-624 002, shall henceforth be Veerapandi, Theni-625 531, shall henceforth be known known as S. -

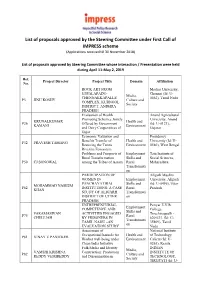

List of Proposals Approved by the Steering Committee Under First Call of IMPRESS Scheme (Applications Received Till 30 November 2018)

List of proposals approved by the Steering Committee under First Call of IMPRESS scheme (Applications received till 30 November 2018) List of proposals approved by Steering Committee whose Interaction / Presentation were held during April 11-May 2, 2019 Ref. Project Director Project Title Domain Affiliation No. ROCK ART FROM Madras University, UPPALAPADU- Chennai (Id: U- Media, CHENNAKKAPALLE 0462), Tamil Nadu P3 JINU KOSHY Culture and COMPLEX, KURNOOL Society DISTRICT, ANDHRA PRADESH Evaluation of Health Anand Agricultural Promoting Schemes Jointly University, Anand KRUNALKUMAR Health and P26 Offered by Government (Id: U-0123), KAMANI Environment and Dairy Cooperatives of Gujarat Gujar Economic Valuation and Presidency Benefits Transfer of Health and University (Id: U- P32 PRAVESH TAMANG Restoring the Teesta Environment 0580), West Bengal Riverine Ecosystem Problems and Prospects of Employment Tata Institute of Rural Transformation Skills and Social Sciences, P50 CJ SONOWAL among the Tribes of Assam Rural Maharashtra Transformati on PARTICIPATION OF Aligarh Muslim WOMEN IN Employment University, Aligarh PANCHAYATIRAJ Skills and (Id: U-0496), Uttar MOHAMMAD NASEEM P62 INSTITUTIONS: A CASE Rural Pradesh KHAN STUDY OF ALIGARH Transformati DISTRICT OF UTTER on PRADESH ENTREPRENEURIAL Periyar E.V.R. Employment COMPETENCE AND College, Skills and PARAMASIVAN ACTIVITIES ENGAGED Tiruchirappalli - P75 Rural CHELLIAH BY PRISONERS IN 620 023. (Id: C- Transformati TAMIL NADU –AN 35809), Tamil on EVALUATION STUDY Nadu Assessment of National Institute Occupational hazards for Health and of Technology, P81 VINAY V PANICKER Worker well-being under Environment Calicut (Id: U- Clean India Initiative 0263), Kerala Folk Media and Identity INDIAN Media, VAMSHI KRISHNA Construction: Production INSTITUTE OF P82 Culture and REDDY VEMIREDDY and Dissemination in TECHNOLOGY, Society TIRUPATI (Id: U- Ref. -

Special Article

Special Article Expectations Of The Indian Parent in the “New World” Priyadarshini Avula-Batchu Introduction: Indians from the subcontinent of India did My mother and I arrived on April 5, 1963. In the not start immigrating to America until the late 1950’s. It months to come John F. Kennedy was assassinated, was not until the 1960’s-1970’s that the great migration there were riots among the colored and white races, and of Indians with traditional values of the old country Martin Luther King was fighting for colored rights. made their cultural resurrection. Hindu temples were The Beatles were grooving, and the Vietnam War was built, community associations formed, and even Indian covered daily in the national news. There were peace cultural associations on university campuses brought the demonstrations that sometimes turned violent. India that they remembered from back home to their new land, AMERICA. Indian cuisine has become quite Dreams change, plans change, and people change. popular in the western world. There are abundant Destiny is not in our hands. My father finished his cookbooks and recipes that have flourished via internet. master’s degree in 18 months at Michigan State and There are several Indian restaurants in the larger cities. then moved on to Iowa State to continue with a PhD. Americans now look at us as part of the melting pot that In 1967 we moved to a small mid-western town near has transcended the American culture. the Ozarks. I was a little girl and my mother was expecting my little sister. Where shall we move? That My story begins…I was born in 1961 in a small town was the question. -

Eighteenth International Congress of Vedanta

EIGHTEENTH INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS OF VEDANTA PROGRAM WEDNESDAY, JULY 15, 2009 Arrive in Dartmouth, MA Check into Hotels/Dorm THURSDAY, JULY 16, 2009 (All meetings will be held in the Maclean Campus Center Auditorium and Rooms 006 and 007) 8:00 – 5:00 PM Conference Registration Desk Open – Auditorium Lobby 8:00 – 9:00 AM Breakfast – Auditorium Lobby 10:00 AM Invocation -Auditorium Vedic Chanting – Gurleen Grewal, University of South Florida 10:15 AM Benediction: Swami Yogatmananda, Vedanta Society, Providence, RI 10:30 AM Welcome: Anthony Garro, Provost University of Massachusetts Dartmouth 10:45 AM Introduction: Bal Ram Singh, University of Massachusetts Dartmouth S. S. Rama Rao Pappu, Miami University Conference Directors ===================================================== 11:00 AM Inaugural Lecture: Auditorium Jagdish N. Srivastava, Colorado State University ―Vedanta and Science” 11:45 – 1:00 PM LUNCH - Faculty Dining/ Cafeteria ================================================= 1 1:00 – 3:00 PM SANKARA - Auditorium Chair: Ashok Aklujkar, University of British Columbia Ivan Andrijanic, University of Zagreb, Croatia ―The Inscription of Sivasoma: Towards the Reconsideration of the date of Sankara‖ Ira Scheptin (Atma Chaitanya) Woodstock, NY ―The Concepts of ‗discrimination‘ and ‗devotion‘ in non-dual Vedanta‖ Ram Nath Jha, Jawaharlal Nehru University ―Sankara‘s Definition, ―Satyam, Jnanam, Anantam Brahma‖ defines Brahman as Indefinable Hope Fitz, Eastern Connecticut State University ` ―Comparison of Confucius on Jen (Human Heartedness) and Gandhi on Ahimsa‖ Korada Subramanyam, University of Hyderabad ―The Purport of Iksatyadhikaranam of Sankara‖ 3:00 – 3:30 PM Coffee Break – Auditorium Lobby 3:30 – 5:00 PM VEDANTA AND CULTURE - Auditorium Chair: Gurleen Grewal, Univ. of South Florida T. K. Parthasarathy, Chennai ―Philosophy of Ubhaya Vedanta‖ Douglas DeMasters, Lake Toxaway, North Carolina ―The Poetics of Cultural Social-Pychodynamics: The Vortex of Vibration, Resonance, Information and Aesthetics‖ P. -

Embellishments Turned Into Challenges. the Transformation of Literary Devices in the Art of the Sāhityāvadhāna*

Cracow Indological Studies Vol. XXII, No. 2 (2020), pp. 127–149 https://doi.org/10.12797/CIS.22.2020.02.07 Hermina Cielas [email protected] (Jagiellonian University, Poland) Embellishments Turned into Challenges. The Transformation of Literary Devices in the Art of the sāhityāvadhāna* SUMMARY: The article focuses on the centuries-old Indian practice of the sāhityāvadhāna, ‘the literary art of attentiveness’, a sub-genre of the avadhāna (‘attention’, ‘attentiveness’), in which extraordinary memory, ability to concen- trate and creative skills are tested through the realisation of various challenges. Numerous tasks within the sāhityāvadhāna have their roots in the theory of lit- erature and poetic embellishments (mostly the so-called śabdā laṅkāras, fig- ures of sound or expression) described by Sanskrit theoreticians. A survey of such devices as niyama, samasyā, datta and vyutkrāntā and their application in the sāhityāvadhāna shows possible re-adjustments of figures of speech brought about by the requirements of practical implementation in the literary performative art. KEYWORDS: avadhāna, sāhityāvadhāna, figures of speech, literary games, performing arts. * This paper is a part of the project Avadhana. Historical and social dimension of the Indian ‘art of memory’ (registration number 2018/28/C/HS2/00415) developed by the author and financed by the National Science Centre (NCN), Poland. 128 Hermina Cielas Introduction Through the centuries of its existence and transformations, the avadhāna (‘attention’, ‘attentiveness’, ‘intentness’) developed into a rich con- glomerate of arts situated in the domain of liminoid cultural perfor- mances encompassing acts of showcasing highly developed cognitive capacities put to test in the form of miscellaneous tasks accomplished in the presence of other people.1 It embodies the idea of heterogene- ity. -

Minutes of 31St GIAC Meeting

Scheme-I : Financial Assistance for Purchase of Books List of proposals kept in 31st Grant in Aid Committee Meeting held on 2nd to 4th November, 2016 Sl. Name & Address of the Price per No. of Amount Title No. Applicant & File No. copy copies (less discount) ASSAMESE 1. Sri. Dilip Kumar Sunya Simantiny Radha Not Chakrabarthy recommended Gari Khana Road (Bye Lane), Ward No. 16, P.O. Bidyapara (Dhubri), Dhubri Dist., Assam-783324 50-1(1)/15-16/Asm/GIA 2. Dr. Ranjula Bora Saikia Yogasastra Gita Aru 150/- 300 33,750/- C/o. Sri Jagnaswar Saikia, Jyotirmay - Bhagawan North Lakhimpur Bar Association, P.O. North Lakhimpur, Lakhimpur Dist., Assam-787001 50-1(2)/15-16/Asm/GIA BENGALI 3. Ms. Soma Datta Manipuri Nrityashaily O 150/- Not D/o Late Paresh Chandra Ranbindranath Prasanga recommended Datta, Tripura 22 No. Ward, Hospital Road Ext., Gandhighat, Agartala, West Tripura, Tripura-799001. 50-2(1)/15-16/Ben/GIA 4. Dr. Birendra Mridha Somen Chanda O 300/- Not C/o Ranjit Kumar Mridha, Pragati sahitya Andolon recommended Rabindra Pally, Daragaon, Jaigaon, Alipurduar, West Benga-736182l. 50-2(2)/15-16/Ben/GIA 5. Dr. Bidyutjyoti Naro Narir Parthoker 80/- Not Bhattacharjee Utso Sandhane recommended 77/13, Ramkrishna Sarani Bylane, Niranjan Nagar, Ghugomali, Eastern Bypass, Near Barnamala Vidyamondir, Siliguri, Darjeeling, West Bengal-734006. 50-2(3)/15-16/Ben/GIA 6. Smt. Anupama Ghosh Bihan Belae Sanjher 200/- Not 2405/06, Beverly Hills (T- Chhayae recommended 36), Lokhandwala Circle, Andheri (West), Mumbai, Maharashtra-400053. 50-2(4)/15-16/Ben/GIA 7. Sri. Dilip Kumar Ishan Nibrchita Bangla : 200/- Not Chakrabarthy Kabya Sankalan recommended Gari Khana Road (Bye Lane), Ward No. -

Sri Gurubhyo Namah: Sri Maatre Namah

Sri Mahaganapathaye namah: Sri Gurubhyo namah: Sri Maatre namah: yadā yadā hi dharmasya glānir bhavati bhārata abhyutthānam adharmasya tadātmānaṁ sṛijāmyaham Sri Vaddiparti Padmakar : Avadhana Sahasra Padma: As Lord Krishna said in bhagavad gita, whenever there is decline in righteousness and an increase in unrighteousness, the lord avataras come to uphold it. The Lord in many forms as gurus, spiritual leaders and speakers lead people in right direction. One the foremost among those gurus is, Brahmasri Vaddiparti Padmakar Gurudev: supreme devotee of Devi, Sahasravadhani in 3 languages, Sripranava peetadhipathi. Gurudev was born to knowledgeable, righteous and famous parents Brahmasri Chalapatirao garu and Srimati Sheshamani garu, in the holy margasira month on a holy day in the brahmi muhurta in year 1966 on Jan1. Jogannapalem in godavari zilla was Gurudev birthplace. Father is pandit in 8 languages and mother is very proficient in sanskrit, hindi languages. With sanchita jnanam and blessings from Devi Saraswati and Srimata Gurudev finished schooling in Ganapavaram. At the age of 3years Gurudev was able to grasp our history and encyclopedism was the gift. At the age of 8 years, Gurudev developed meditation and concentration power with the divine blessing of Srisailam Parvathi Parameshwara, Kumara, Vigneshwara, Vasuki and blessings from Mata Annapurna devi,. Just at the age of 16 years Gurudev grasped the essence of lacs of mahabharata slokas. He continued to graduate with an M.A. in Sanskrit and Hindi languages, a gold medal due the proficiency in the languages, and another gold medal between contesters of all gold medalists from other Universities. Gurudev’s first lecture on Sundarakanda part of Valmiki Ramayana was at the age of 20yrs in a village Ardhavaram 8Kms from Ganapavaram. -

Journal of Marketing Vistas

Journal of MarketingISSN 2249-9067Vistas Journal of Marketing Vistas Volume 3, No 1, January-June 2013 Preference Analysis of Tourists in India with Special Reference to Andhra Pradesh Shulagna Sarkar Crisis Communication and Response Strategies: A Study of Select Brands Avadhanam Ramesh and Ravi Prakash Kodumagulla Consumers’ Preference Towards Organized Retail Store While Buying Apparel: A Case Study of Ahmedabad City RP Patel and Praneti Shah Drivers of Customers’ Adoption of e-Banking: An Empirical Investigation Ravinder Vinayek and Preeti Jindal Measurement of Service Quality: A Life Insurance Industry Perspective Kunjal Sinha The Dubai Shopping Festival: A Study of Visitors’ Perceptions Shohab Sikandar Desai 1 ISSN 2249-9067 Journal of Marketing Vistas Volume 3, No 1, January-June 2013 Contents Preference Analysis of Tourists in India with 1 Special Reference to Andhra Pradesh Shulagna Sarkar Crisis Communication and Response Strategies: 13 Study of Select Brands Avadhanam Ramesh and Ravi Prakash Kodumagulla Consumers’ Preference Towards Organized Retail Store 30 While Buying Apparel: A Case Study of Ahmedabad City RP Patel and Praneti Shah Drivers of Customers’ Adoption of e-Banking: 40 An Empirical Investigation Ravinder Vinayek and Preeti Jindal Measurement of Service Quality: 54 A Life Insurance Industry Perspective Kunjal Sinha The Dubai Shopping Festival: 67 A Study of Visitors’ Perceptions Shohab Sikandar Desai Journal of Marketing Vistas Preference Analysis of Tourists in India with Special Reference to Andhra Pradesh Shulagna Sarkar Asst. Professor Institute of Public Enterprise, Hyderabad Abstract Tourism has become a popular global leisure activity largely affecting the cities, states and countries’ economies. The objectives of the paper are to elaborate the factors influencing the domestic and international tourists for choosing tourist destinations and to compare the preferences of domestic and international tourists. -

Financial Year

GITANJALI GEMS LIMITED Statement Showing Unpaid / Unclaimed Dividend as on Annual General Meeting held on September 19, 2009 for the financial year 2008‐09 First Name Last Name Address Country State District PINCode Folio Number of Investment Type Amount Proposed Date Securities Due(in Rs.) of transfer to IEPF (DD‐MON‐ YYYY) JYOTSANA OPP SOMESHWAR PART 3 NEAR GULAB TOWER THALTEJ AHMEDABAD INDIA GUJARAT AHMEDABAD 380054 GGL0038799 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 63.00 01‐OCT‐2016 MANISH BRAHMBHAT 16 MADHUVAN BUNGLOW UTKHANTHESWAR MAHADEV RD AT DEGHAM DIST GANDHINAGAR DEHGAM INDIA GUJARAT GANDHI NAGAR 382305 GGL0124586 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 63.00 01‐OCT‐2016 BHARAT PATEL A‐8 SHIV PARK SOC NR RAMROY NAGAR N H NO 8 AHMEDABAD INDIA GUJARAT GANDHI NAGAR 382415 GGL0041816 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 63.00 01‐OCT‐2016 SHARMISTA GANDHI 13 SURYADARSHAN SOC KARELIBAUG VADODARA INDIA GUJARAT VADODARA 390228 GGL0048293 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 63.00 01‐OCT‐2016 C MALPANI SURAT SURAT INDIA GUJARAT SURAT 395002 GGL0049550 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 63.00 01‐OCT‐2016 SONAL SHETH C/O CENTURION BANK CENTRAL BOMBAY INFOTECH PARK GR FLR 101 K KHADEVE MARG MAHALAXMI MUMBAI INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400011 GGL0057531 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 63.00 01‐OCT‐2016 CHIRAG SHAH C/O CENTURION BNK CENTRAL BOMY INFOTECH PARK GR FLR 101 KHADVE MAWRG MAHALAXMI MUMBAI INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400011 GGL0057921 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 63.00 01‐OCT‐2016 NUPUR C/O CENTURION -

The Eightfold Gymnastics of Mind: a Preliminary Report on the Idea and Tradition of Asfâvadhâna

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Cracow Indological Studies Provided by Jagiellonian Univeristy Repository vol. XIV (2012) Lidia Sudyka & Cezary Galewicz (Jagiellonian University, Kraków) The eightfold gymnastics of mind: a preliminary report on the idea and tradition of asfâvadhâna SUMMARY: The present paper stems from a field study initiated in 2006-2008 in Kar nataka and Andhra Pradesh. It aims at drawing a preliminary image of the hitherto unstudied art of avadhâna (Skt.: ‘attentivness, concentration’) of which astâvadhâna (literally: eightfold concentration) seems to be a better known variety. The paper presents a selection of epigraphic and literary evidence thereof and sketches a histori cal and social background of avadhâna to go with a report on the present position of its tradition of performance as well as prevailing set of rules. KEYWORDS: literary cultures, performing arts, asfâvadhâna, avadhâna, intellectual literary games, Kâmasütra, kavigosthi Foreword (by Cezary Galewicz) Rather than an outcome of a completed project, this presentation is meant to be an introduction into a presumably new research area situated on the crossroads of literary studies and social anthropology. It concerns a tradition of a particular type of literary gaming known by the name of avadhâna (Skt. ‘attention, concentration’), its history, geographical and cultural location as well as its present status. To our best knowledge, the living art and tradition of avadhâna have remained 170 Lidia Sudyka & Cezary Galewicz so far outside the focus of academic attention. For this reason at least, the present paper is a pioneering study. It addresses also a more gen eral problem of how to do field research and how to describe living or revived performing traditions within literary cultures of South Asia. -

History of Telugu Literature

History of Telugu Literature Prof. C. Mrunalini Andhra Pradesh Map Telugu language Telugu language has a history of 1500 years • In the first phase, it was in inscriptions that the language took literary shape • Telugu language has been accorded Classical Status along with Sanskrit, Tamil and Kannada by the Government of India Telugu, Italian of the East • Telugu is a vowel-ending language • It is one of the 4 Dravidian Languages • Telugu has been hailed as “Italian of the East’ because of its melodious quality • Telugu is the second highest spoken language of India, after Hindi The Mahabharata • Three poets- – Nannaya – Tikkana – Errana • Translated Vyasa’s Mahabharata into Telugu • Translation of Mahabharata was started by Nannaya in the 11th century on the request of the East Chalukya king Rajaraja Narendra. Mahabharatam The Mahabharata • Nannaya wrote two and a half parvas and Tikkana wrote from 4th parva till the end. Errana completed the part left out by Nannaya in the third, Aranya parva. These three are known as Kavitraya (The poet Trinity) • Mahabharata is the first comprehensive literary text written in telugu (1053 A.D) Major Genres of Classical Age • The main genres from 11th century to 18th century were 3 fold. Important are; – Itihasam, Puranam, Kavyam • Itihasam was the story of kings and gods with some historical basis. The main message would be Truth and dharma • Purana was the story of the Gods and their Avatars mainly intending to inspire devotion and spiritual thinking Major Genres of Classical Age (contd..) • Kavya is a combination of myth and fiction. Meant to please with its style and language.